Political Science – 1st Year

Paper – II (PYQs Soln.)

Theory and Practice of Modern Governments

Unit I

Language/भाषा

INTRODUCTION

- Comparative politics is a field of political science using an empirical approach and comparative method.

- It involves comparisons of political experience, behavior, and processes.

- Studying governments is a key aspect of studying politics.

- Comparative study of government and politics is essential for political science.

- Comparative politics analyzes and compares different political systems across societies.

- A major challenge in political science was developing a broadly applicable theory of the political system.

- David Easton developed a theory addressing this challenge.

- Outputs of a political system are authoritative decisions and actions for distributing and dividing values.

- The unit introduces the nature and significance of comparative politics.

DEFINITION, NATURE, AND SCOPE

- Comparative government evolved over time, studying political systems and procedures across countries and periods.

- The field gained prominence in the 1950s, but its roots are older, with Aristotle being a foundational figure.

- Comparative study highlights surprising differences in the lives of people in different nations.

- Somalia is a poor nation in the Horn of Africa with a history of ancient civilization but now faces adversity due to communist rule and civil war.

- The new coalition government in Somalia, with international help, has tried to reform the country but conditions remain challenging.

- The United States is a superpower with a large area and population, gaining independence on July 4, 1776.

- The U.S. faced a great depression after World War I but emerged as a superpower post-World War II, being the first to possess nuclear weapons.

- The U.S. has made significant progress over the years.

- Comparative politics relies on conscious comparisons of political experience, institutions, behavior, and processes across different government systems.

Need for the study of comparative governments

- Comparative study of governments helps evaluate one’s own political system and reduces ethnocentrism.

- The study of government is crucial in political science, focusing on structure and behavior.

- Modern governments are essential for development, especially in developing nations.

- Political systems vary widely, with no two governments being identical.

- Different societies require different governments to meet their needs.

- Political science courses often include surveys of various governmental systems worldwide.

- The decline of some powers and the rise of new nations affect the study of political systems.

- Comparative analysis of political structures and processes is essential in political science.

- Comparative government is a core part of political science.

- Aristotle was the first to compare political systems and develop theories.

- Comparative government has been a significant subject since Aristotle.

- Scholars have long compared foreign cultures with varying complexity.

- The Cold War era and the rise of informal politics influenced comparative government studies.

- The behavioral revolution in the 1950s and 1960s transformed the study of comparative government.

- Improvements in concepts, methods, and interdisciplinary studies revolutionized the field.

Popular Definitions of Comparative Politics

- M. G. Smith: Comparative politics studies political organizations, their properties, correlations, variations, and modes of change.

- Roy C. Macridis and Robert Ward: Comparative politics involves government structure and also society, historical heritage, geography, resources, social and economic organizations, ideologies, value systems, political style, parties, interests, and leadership.

- M. Curtis: Comparative politics examines significant regularities, similarities, and differences in political institutions and behavior.

- E. A. Freeman: Comparative politics analyzes various forms of government and diverse political institutions.

- Comparative politics involves institutional and mechanistic arrangements and empirical and scientific analysis of non-institutionalized and non-political determinants of political behavior.

Nature of Comparative Governments

- Comparative politics analyzes and compares different political systems across societies.

- It involves three key associations: political activity, political process, and political power.

- Political activity deals with conflict resolution and the struggle for power.

- Political process transforms signals and information from non-state agencies into authoritative values.

- Politics involves studying power, power relations, and conflict resolution through legitimate power.

- Features of contemporary comparative politics:

- Analytical Research: Emphasizes analytical, empirical research over mere descriptive studies, providing clearer views of government activities, structures, and functions.

- Objective Study: Focuses on empirical study and scientifically demonstrable values in political science.

- Study of Infrastructures: Analyzes individual, group, and system interactions with their environment.

- Study of Developing and Developed Societies: Includes both developing and developed political systems, with modern political scientists advocating for the study of developing nations.

- Contemporary comparative politics offers a realistic and comprehensive view of global political phenomena, moving beyond traditional norms.

APPROACHES TO COMPARATIVE POLITICS

Major Approaches

- Comparative politics and comparative government are often used interchangeably but have differences.

- Comparative government studies different political systems focusing on institutions and functions.

- Comparative politics has a broader scope, including non-state politics.

- Political science concerns the goals of a good society, governing methods, public political actions, and connections between society and government.

- Key concern of political science is power—its distribution, participation, representation, and impact by growth and change.

- Comparative politics is interesting due to various approaches, methods, and techniques to realize political reality.

- David Apter defines key themes in political analysis:

- Paradigm: Framework of ideas for analysis, combining philosophical assumptions and criteria of valid knowledge.

- Theory: Generalized statement summarizing actions of variables.

- Method: Way of organizing a theory for application to data, known by names of conceptual schemes.

- Technique: Links method to data, varies in observation and recording empirical information.

- Model: Simplified way of describing relationships, constructed from paradigms, theories, methods, or techniques.

- Strategy: Combines elements to solve a research problem, ensuring quality and integrity.

- Research Design: Converts strategy into an operational plan for fieldwork or experiments.

The traditional approach

- The traditional approach to comparative government emerged as a response to 19th-century historicism.

- It focused on historical examination of Western political institutions from early to modern times.

- Traditionalists either philosophized about democracy or conducted formal and legal studies of governmental institutions.

- The approach was configurative, treating each system as a unique entity.

- It was descriptive rather than problem-solving, explanatory, or analytic, and was limited to forms of government and foreign political systems.

- Roy Macridis summarized major features of the traditional approach as non-comparative, descriptive, parochial, static, and monographic.

- Almond and Powell identified three major criticisms of the pre-World War II approach:

- Parochialism

- Configurative analysis

- Formalism

- Harry Eckstein noted the influence of abstract theory, formal legal studies, and configuration studies.

- The traditional approach primarily focused on Western political systems and representative democracies.

- It studied countries like Britain, the US, France, Germany, Italy, and Russia, with limited focus on Asia, Africa, and Latin America.

- Cross-cultural studies were almost nonexistent.

- The approach was formal, focusing on governmental institutions and legal models rather than performance, interaction, and behavior.

- It neglected informal factors and non-political determinants of political behavior.

- The study was descriptive, with little attempt to develop general theories or verify hypotheses.

- The empirical deficiency led to a drive for behaviorism, referred to as ‘empirical theory’ by Robert Dahl.

- The dissatisfaction with traditionalism led to a reconstruction of the discipline.

- Three factors contributing to behavioral innovation in political science:

- Changes in philosophy

- Changes in social sciences

- Technological innovations in research

- Peter Merkl emphasized the rising importance of developing areas and their impact on world politics.

- Almond and Powell cited key developments causing the shift:

- Emergence of numerous nations with diverse cultures

- Social institutions and political traits

- Decline of Atlantic community dominance

- Changing balance of power

- Emergence of communism as a power factor

The revolution in comparative politics

- Dynamic efforts in innovation led to creation of new rational order.

- Sidney Verba described it as ‘A revolution in comparative politics’.

- Principles behind the revolution: look beyond description to theoretically relevant problems.

- Look beyond formal institutions of government to political process and political functions.

- Look beyond Western Europe to new nations of Asia, Africa, and Latin America.

- Almond and Powell emphasized search for more comprehensive scope.

- Search for realism, precision, and theoretical order.

Nature and directions of the transformation

- Behavioural approach is generally accepted in the study of government and politics.

- Institutional analysis is replaced by process mode analysis.

- Behaviourists focus on the behaviour of people and groups, not structures or institutions.

- Process mode captures the dynamic quality of political life.

- Focus shifts from state to empirical investigation of human relations.

- Smaller units like individuals and groups become the centre of study.

- Institutions are redefined as systems of individual behaviour or social action.

- Methods include building complex models, using quantitative techniques, and employing computers for data management.

- Sydney Verba notes the rich theoretical literature, frameworks, paradigms, and system models resulting from the revolution.

- These models are abstract but useful for understanding political behaviour and providing a foundation for further study.

New Approaches to the Study of Government and Politics

General Systems Theory

- Behavioural political analysis represents a significant transformation from traditional approaches.

- The behavioural approach focuses on the behaviour of individuals and groups rather than institutions or ideologies.

- It emphasizes the dynamic quality of political life and avoids static structural analysis.

- The state is no longer the central concept; attention is on human relations and interactions.

- Institutions are redefined as systems of related individual behaviour.

- Methods include building complex models, using quantitative techniques, and employing computers for data management.

- Sidney Verba highlights the creation of theoretical literature, frameworks, and models as key outcomes.

- Systems theory, originating in natural sciences, offers a broad perspective for political analysis.

- Systems theory defines a system as a set of interacting elements.

- David Easton defines a political system as the behaviour or interactions for making and implementing decisions in society.

- The political system includes the political community, regime, and political authorities.

- The general systems theory provides a macro and micro analytical framework for studying politics.

- Fundamental concepts include open vs. closed systems, stability, equilibrium, adaptation, and change.

- The theory helps integrate micro and macro studies and facilitates interdisciplinary communication.

- Criticisms include its limited handling of political power, voting behaviour, and policy-making.

- The theory is seen as conservative and reactionary, with challenges in empirical application.

Offshoots of the Systems Theory

- Behaviourists adapted the general systems theory framework to political science.

- New techniques in political analysis were developed from this adaptation.

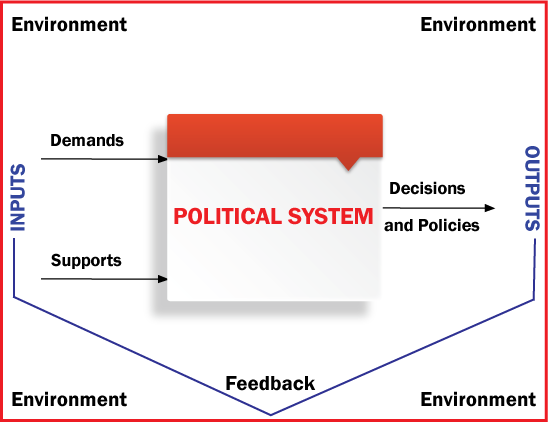

- David Easton’s ‘input-output’ model analyzes political systems by examining inputs (demands and support) and outputs (policy decisions and actions).

- Structural functionalism, a significant derivative of systems analysis, focuses on decision-making models of political systems.

- Another systems theory approach uses communications theory to model political integration among countries or ethnic communities.

Input–Output Analysis

- David Easton developed a unique systemic approach for political analysis, distinct from other social sciences.

- His book “A System Analysis of Political Life” (1965) introduced a new way to explain political phenomena.

- Easton criticized the structural-functional approach for lacking concepts to handle all system types and being imprecise.

- His empirical theory is called the ‘general theory of politics’, aiming for a unified theory for national and international politics.

- Easton focuses on analyzing conditions for political system survival over time rather than power-relations.

- He views the political system as a subsystem of society operating within an environment.

- Describes the political system as a system of interactions for authoritative allocations.

- Features of a political system include a regular pattern of relationships among actors, universality, and authority.

- The system processes inputs (demands and support) into outputs (authoritative decisions and actions).

- Inputs include demands (requests for action) and support (favorable attitudes).

- Overloading in a system occurs due to volume stress or content stress from excessive or complex demands.

- Support is crucial for both selection and processing of demands.

- Distinguishes between overt support (direct actions) and covert support (non-hostile attitudes).

- Outputs are authoritative decisions and actions for value distribution.

- Feedback loops are essential for generating specific support and making the system dynamic.

- Stability depends on structural mechanisms (political parties, media, etc.), cultural mechanisms (customs, mores), and procedural mechanisms.

- The political system is a dynamic, cyclical operation with programmed goals, facing stress and regulatory processes.

- Input-output analysis is a comprehensive technique for comparative analysis of political systems.

- Eugene Meehan highlights Easton’s contribution to systems analysis and functional theory in political science.

- The approach is dynamic, addressing change, stability, and regulatory responses.

- Criticisms include its focus on system-persistence, limited interaction scope, elitist orientation, and focus on functional rather than revolutionary change.

Structural–Functional Analysis

- Structural–functional analysis is a major framework in political science, emerging from early 20th-century anthropology, particularly by Malinowski and Radcliffe-Brown.

- Gabriel Almond adopted this approach for comparative politics.

- It focuses on system-maintenance and regulation, asking what structures fulfill basic functions and what conditions govern a system.

- A political system consists of structures that are patterns of action and institutions performing functions defined as objective consequences for the system.

- Functions are recurring actions for system preservation, while dysfunctions are detrimental to system growth.

- Robert Merton distinguished between manifest functions (intended and recognized) and latent functions (unintended and unrecognized).

- Structures are vital and can fulfill various functions; a single structure can have multiple functions with different outcomes.

- Almond and Powell observed that specialized structures in systems like the U.S. are multifunctional.

- Structural–functional analysis identifies ‘conditions of survival’ essential for maintaining a system’s characteristics over time.

- Marion Levy, Jr. identified four functional requisites of social systems: goal-attainment, adaptation, integration, and pattern-maintenance.

- Gabriel Almond’s political functional requisites include four input functions: political socialization and recruitment, interest articulation, interest aggregation, and political communication.

- Output functions include rule-making, rule-application, and rule-adjudication.

- Input functions are performed by non-governmental subsystems, while output functions are carried out by traditional governmental agencies.

- Almond’s structural–functional analysis aims to develop a universal analytical vocabulary for studying non-Western states, particularly ‘third world’ countries.

- Defines politics as integrative and adaptive functions of a society using coercion.

- Almond’s political system involves interactions for integration and adaptation through legitimate order-maintaining or transforming mechanisms.

- Stresses interdependence between political and societal systems, with common properties across all political systems.

- Almond acknowledges criticisms of stability-orientation and conservatism, clarifying his framework as one of interdependence, not harmony.

- The approach has been widely adopted for providing standard categories for different political systems and has influenced comparative politics.

- Criticisms include value orientations, tautological premises, and vague conceptual units.

- Meehan views Almond’s work as a classificatory scheme or an imperfect model rather than a full theory.

- Criticized for its tendency to force divergence into a systematic framework and its inability to effectively analyze complex political realities in Third World countries.

- The analysis is considered static, favoring stability and status quo, and may struggle with swift or violent changes.

- Caution is advised in applying structural–functional analysis due to its limitations in dealing with change.

Decision-Making Theories

- Decision-making is a key aspect of studying government and politics but is considered less successful among new approaches.

- Politics involves allocating values through decision-making processes.

- The process includes techniques, methods, procedures, and strategies used to make decisions.

- A political system functions as a mechanism for decision-making.

- Efficiency in a political system is gauged by its ability to make widely accepted decisions.

- The dynamics of politics involve the interaction between social configuration, ideology, and governmental organs.

Marxist Methodology

- Despite claims of progress in comparative politics, sophisticated empirical models remain undeveloped.

- Systems analysis and structural-functionalism, among other approaches, have fallen short of satisfactory methodological orientations.

- Key questions include the scientific methodology of Marxism and its applicability in comparative politics.

- Marxism is based on dialectical and historical materialism, focusing on interdependence, movement, and development in social phenomena.

- Marx asserts that the mode of production determines social, political, and intellectual processes, not consciousness.

- Marx’s concept of ‘class’ refers to economic categories like wage laborers, capitalists, and landowners based on the capitalist mode of production.

- Methodological themes in Marxism include searching for social bias, rigorous scientific efforts, and explanations of human activity through historical and economic contexts.

- Marxism emphasizes the importance of economic elements in social structures, recognizing reciprocal interaction with political, social, and cultural elements.

- Key aspects include searching for contradictions, using ‘class’ in social development, recognizing technology as a variable, and distinguishing between causes and symptoms of capitalist crisis.

- Marxism examines productive forces, productive relations, and ideological superstructures in social structures.

- Application of Marxism in comparative politics includes analyzing property relations, focusing on ownership rather than possession.

- The social division of labor should be examined, with emphasis on societal rather than localized divisions.

- Comparing political development involves assessing the stage of economic activity in different societies.

- Marxist theory explains state-society relationships and political authority in different stages of economic development.

- Historical background is crucial for understanding the nature and direction of political systems.

- Marxist analysis addresses problems of instability and change better than systems and structural-functional theories.

- Marxism provides a framework to search for historical process laws applicable to specific contexts, but requires extensive research.

- Marx’s framework may not account for 20th-century developments, but his approach remains relevant and adaptable.

- Marx acknowledged that laws are modified by numerous conditions in actual practice.

The modern approach is fact based and lays emphasis on the factual study of political phenomenon to arrive at scientific and definite conclusions. The modern approaches include sociological approach, economic approach, psychological approach, quantitative approach, simulation approach, system approach, behavioural approach, Marxian approach etc.

Broadly speaking, modern or contemporary approaches to the study of politics signify a departure from traditional approaches in two respects: (a) they attempt to establish a separate identity of political science by focusing on the real character of politics; and (b) they try to understand politics in totality, transcending its formal aspects and looking for those aspects of social life which influence and are influenced by it.

Normative methods generally refer to the traditional methods of inquiry to the phenomena of politics and are not merely concerned with “what is” but “what ought to be” issues in politics. Its focus is on the analysis of institution as the basic unit of study. However with the advent of industrialisation and behavioural revolution in the field of political science, emphasis shifted from the study “what ought to” to “what is”. Today political scientists are more interested in analysing how people behave in matters related to the state and government.

A new movement was ushered in by a group of political scientists in America who were not satisfied with the traditional approach to the analysis of government and state as they felt that tremendous exploration had occurred in other social sciences like sociology, psychology anthropology etc. which when applied to the political issues could render new insights. They now collect data relating to actual political happenings. Statistical information coupled with the actual behaviours of men, individually and collectively, may help the political scientists in arriving at definite conclusions and predicting things correctly in political matters. The quantitative or statistical method, the systems approach or simulation approach in political science base their inquiry on scientific data and as such are known as modern or empirical method.

System Approach

This approach belongs to the category of modern approach. This approach makes an attempt to explain the relationship of political life with other aspects of social life. The idea of a system was originally borrowed from biology by Talcott Parsons who first popularized the concept of social system. Later on David Easton further developed the concept of a political system. According to this approach, a political system operates within the social environment. Accordingly, it is not possible to analyze political events in isolation from other aspects of the society. In other words, influences from the society, be it economic, religious or otherwise, do shape the political process.

The systems approach as developed by David Eason can be analyzed with the help of a diagram as follows:

The political system operates within an environment. The environment generates demands from different sections of the society such as demand for reservation in the matter of employment for certain groups, demand for better working conditions or minimum wages, demand for better transportation facilities, demand for better health facilities, etc.. Different demands have different levels of support. Both ‘demands’ and ‘supports’ constitute what Easton calls ‘inputs.’ The political system receives theses inputs from the environment. After taking various factors into consideration, the government decides to take action on some of theses demands while others are not acted upon. Through the conversion process, the inputs are converted into ‘outputs’ by the decision makers in the form of policies, decisions, rules, regulations and laws. The ‘outputs’ flow back into the environment through a ‘feedback’ mechanism, giving rise to fresh ‘demands.’ Accordingly, it is a cyclical process.

Structural Functional Approach

This approach treats the society as a single inter–related system where each part of the system has a definite and distinct role to play. The structural-functional approach may be regarded as an offshoot of the system analysis. These approaches emphasize the structures and functions. Gabriel Almond is a supporter of this approach. He defines political systems as a special system of interaction that exists in all societies performing certain functions. According to him, the main characteristics of a political system are comprehensiveness, interdependence and existence of boundaries. Like Easton, Almond also believes that all political systems perform input and output functions. The Input functions of political systems are political socialisation and recruitment, interest-articulation, interest-aggression and political communication. Again, Almond makes three-fold classifications of governmental output functions relating to policy making and implementation. These output functions are-rule making, rule application and rule adjudication. Thus, Almond believes that a stable and efficient political system converts inputs into outputs.

Communication Theory Approach

This approach tries to investigate how one segment of a system affects another by sending messages or information. It was Robert Weiner who first spoke about this approach. Later on Karl Deutsch developed it and applied it in Political Science. Deutsch believes that the political system is a network of communication channels and it is self regulative. He further believes that the government is responsible for administering different communication channels. This approach treats the government as the decision making system. According to Deutsch, the four factors of analysis in communication theory are – lead, lag, gain and load.

Decision Making Approach

This approach tries to find out the characteristics of decision makers as well as the type of influence the individuals have on the decision makers. Scholars like Richard Synder and Charles Lindblom have developed this approach. A political decision which is taken by a few actors influences a larger society and such a decision is generally shaped by a specific situation. Therefore, it takes into account psychological and social aspects of decision makers also.

Importance of the Modern Approach to the Study of Comparative Politics

The study of Comparative Politics has undergone significant transformation, especially in the context of an increasingly globalized world. Traditionally, Comparative Politics involved analyzing political institutions, constitutions, and systems within specific countries, often adopting a state-centric view. However, as scholars faced the complexities of modern societies, especially post-World War II, they found that these traditional methods were insufficient to address the dynamic and diverse political phenomena. Hence, a modern approach to Comparative Politics emerged.

Scientific Orientation and Methodology

The modern approach to Comparative Politics is distinctly scientific, using empirical research methods to achieve an objective understanding of political phenomena. Unlike traditional approaches, which often relied on normative analysis and theoretical speculation, the modern approach emphasizes evidence-based conclusions. Comparative Politics scholars today use methodologies such as case studies, comparative historical analysis, and statistical techniques to examine political systems and behaviors across different contexts.

This scientific orientation has introduced hypothesis testing, data collection, and quantitative analysis to the field. Through these methods, researchers can generalize findings across political systems and identify patterns that are not confined to any single country or system. The reliance on empirical research allows for a more precise and comprehensive understanding of how different political variables interact and influence each other. This methodology is particularly valuable for policy-making as it provides evidence that can be used to design effective political interventions and predict outcomes.

Interdisciplinary Approach

Another key feature of the modern approach is its interdisciplinary nature. Comparative Politics today integrates insights from economics, sociology, anthropology, psychology, and history to provide a holistic view of political systems and behaviors. For instance, the study of political economy, a subfield within Comparative Politics, examines how economic factors influence political institutions and vice versa. By incorporating theories from sociology, Comparative Politics scholars can explore social structures, culture, and group dynamics that influence political behavior and institutions.

The interdisciplinary approach is essential for understanding the complex realities of modern political issues, such as globalization, human rights, migration, and environmental politics. These issues are inherently multifaceted and cannot be fully understood through a purely political or institutional lens. An interdisciplinary framework allows scholars to analyze political phenomena from multiple perspectives, creating a more nuanced understanding that is crucial for addressing contemporary global challenges.

Behavioral Focus

The modern approach to Comparative Politics places significant emphasis on the behavioral aspects of political actors. Traditional approaches tended to focus on formal institutions like constitutions, laws, and government structures, often ignoring the actual behavior of political actors within these frameworks. The behavioral approach, which gained prominence in the 1950s and 1960s, shifted the focus to individuals and groups, examining their beliefs, attitudes, and actions within political contexts. This perspective considers not only what political institutions dictate but also how people behave within these institutions.

Behavioral studies have provided valuable insights into voting behavior, public opinion, political participation, and the role of ideology. For instance, comparative research on voter behavior has shown how cultural, social, and economic factors influence voting patterns across different societies. By understanding the motivations and actions of individuals, scholars can better explain the outcomes of political processes and predict future political trends. This behavioral emphasis is essential in an era where individual actions—such as participation in social movements or public protests—play a significant role in shaping political landscapes.

Global and Comparative Perspective

The modern approach to Comparative Politics is inherently comparative and global. By studying a variety of political systems, scholars can identify universal patterns and unique deviations that characterize different types of governance and political structures. This comparative perspective helps in challenging ethnocentric biases and expanding our understanding of political systems beyond a single nation. By comparing democracies, authoritarian regimes, and hybrid systems, researchers can identify what makes certain political institutions resilient or fragile.

In a globalized world where issues like climate change, terrorism, and economic inequality transcend national borders, a comparative approach is indispensable. Comparative Politics helps policymakers learn from the successes and failures of different countries. For instance, studies on welfare systems in Nordic countries have provided insights into how governments can effectively balance economic growth with social equity. Similarly, comparative studies on political corruption have revealed the importance of transparency and accountability mechanisms in promoting good governance.

Focus on Power Dynamics and Social Change

The modern approach to Comparative Politics also pays significant attention to power dynamics and social change. Unlike traditional approaches, which often viewed political systems as static entities, the modern perspective recognizes that political systems are constantly evolving. This approach emphasizes the role of power struggles, social movements, and ideological conflicts in shaping political landscapes. For instance, the rise of populist movements in various parts of the world can be understood through the study of changing power dynamics, economic grievances, and identity politics.

By focusing on power relations, the modern approach enables a more critical analysis of political systems. It uncovers the underlying power structures that maintain inequality, oppression, or authoritarianism, offering insights into how marginalized groups can mobilize for social change. The focus on social change is particularly relevant in the 21st century, as societies grapple with issues of racial justice, gender equality, and economic reform. Comparative Politics scholars analyze how different countries address these issues, providing lessons that can inspire social change in other regions.

Importance in Policy-Making

One of the practical benefits of the modern approach to Comparative Politics is its application in policy-making. By providing evidence-based insights into the functioning of political systems, this approach helps policymakers design effective and context-sensitive policies. Comparative research allows policymakers to understand which policies are likely to succeed or fail in particular contexts. For example, studies on healthcare systems across countries have shown how universal healthcare models can be implemented effectively, while research on electoral systems helps in designing fair and representative political institutions.

Furthermore, the modern approach to Comparative Politics helps in understanding international relations and cooperation. In an interconnected world, the decisions of one country can have far-reaching consequences. Comparative Politics provides a framework for understanding these interdependencies and for developing policies that promote cooperation and conflict resolution.

The United Kingdom has an uncodified constitution. The constitution consists of legislation, common law, Crown prerogative and constitutional conventions. Conventions may be written or unwritten. They are principles of behaviour which are not legally enforceable, but form part of the constitution by being enforced on a political, professional or personal level. Written conventions can be found in the Ministerial Code, Cabinet Manual, Guide to Judicial Conduct, Erskine May and even legislation. Unwritten conventions exist by virtue of long-practice or may be referenced in other documents such as the Lascelles Principles.

In the context of political science and constitutional studies, conventions refer to established practices or unwritten rules that guide political conduct but are not legally enforceable. While they do not have the force of law and cannot be enforced by courts, conventions are essential in shaping political behavior and ensuring the smooth functioning of the government. Conventions are especially significant in political systems like the United Kingdom, where there is no written constitution, and the legal framework largely relies on a combination of statutes, judicial decisions, and conventions.

Understanding Conventions in the British Political System

Conventions can be understood as traditional rules or accepted practices that have evolved over time through continuous usage. They are not codified in any single document, unlike constitutional statutes, but are accepted as a key part of the British unwritten constitution. These conventions have developed to bridge gaps in the legal framework and provide a practical means of managing the complexities of the government. According to A.V. Dicey, a prominent constitutional theorist, conventions are the “customs, practices, maxims, or precepts which are not enforced or recognized by the courts.” Despite their lack of legal enforceability, conventions are morally binding and are generally adhered to by those in power.

Conventions cover various areas, such as the powers of the monarchy, the relationship between the House of Commons and the House of Lords, and the roles of the Prime Minister and Cabinet. Their adherence is based on a shared understanding and respect for the constitutional framework and an acknowledgment of the consequences of violating these norms. The British political system relies heavily on conventions to function smoothly, as they supplement statutory laws and common law principles, providing continuity, flexibility, and adaptability to the evolving needs of governance.

Role of Conventions in the British Political System

Conventions play a vital role in the British political system by shaping the structure and functioning of government institutions. They serve to regulate relationships among the executive, legislative, and judicial branches, maintain checks and balances, and uphold democratic principles. Below are some of the key roles conventions play in the British political system:

1. Regulating the Powers of the Monarchy

One of the fundamental roles of conventions in the British political system is to regulate the powers of the monarchy. Although the United Kingdom is a constitutional monarchy, where the monarch is the head of state, most powers associated with the monarchy are exercised on the advice of the government. For instance, the convention of Royal Assent dictates that the monarch must give assent to any legislation passed by Parliament, but by convention, this assent is always granted, and the monarch does not have the discretion to reject it.

Similarly, the convention that the monarch acts on the advice of the Prime Minister ensures that the monarchy remains politically neutral. For example, the monarch’s formal appointment of a Prime Minister is guided by the convention that the leader of the majority party in the House of Commons is chosen. By regulating these aspects, conventions preserve the monarchy as a symbolic institution while transferring political power to elected representatives.

2. Guiding the Prime Minister and Cabinet

Conventions also define the roles and responsibilities of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, which are not explicitly outlined in any statute. The British political system operates under the Cabinet system, where the Prime Minister, as the head of government, is supported by a Cabinet of ministers who are responsible for different areas of governance. The collective responsibility convention mandates that all Cabinet members must publicly support government policies, even if they privately disagree. If a minister cannot abide by this, they are expected to resign.

The convention of individual ministerial responsibility requires ministers to be accountable to Parliament for their actions and the actions of their departments. This principle maintains accountability within the executive and reinforces Parliament’s authority to oversee the actions of the government. Conventions governing the Prime Minister’s power to call elections, appoint ministers, and manage parliamentary business contribute to the effective functioning of the executive and ensure that power is exercised responsibly.

3. Ensuring the Sovereignty of Parliament

The convention of Parliamentary Sovereignty is a core principle of the British constitution, establishing Parliament as the supreme legislative body. This principle implies that no other institution, including the monarchy or the judiciary, can override parliamentary decisions. Conventions play a key role in maintaining this sovereignty by regulating the interaction between Parliament and other branches of government.

For example, the convention that the House of Lords defers to the House of Commons in matters of finance ensures that the elected body retains control over taxation and government spending. Similarly, the Salisbury Convention holds that the House of Lords should not reject a bill that fulfills a manifesto commitment of the government, thereby respecting the mandate of the elected House of Commons. These conventions protect parliamentary sovereignty and uphold the democratic principle of representation by ensuring that elected officials hold the primary legislative power.

4. Governing the Relationship Between the Executive and Parliament

The relationship between the executive and Parliament is largely governed by conventions. For instance, the Prime Minister’s Questions (PMQs) and parliamentary debates serve as a mechanism for holding the executive accountable. By convention, the Prime Minister and ministers must regularly appear in Parliament to answer questions from Members of Parliament (MPs), ensuring transparency and accountability.

Additionally, the convention that Parliament must approve military action (though not legally binding) has gained strength in recent years. For example, the vote on the Iraq War in 2003 and the intervention in Syria in 2013 demonstrate how conventions can evolve in response to public expectations for parliamentary oversight. These conventions not only maintain a check on executive power but also enable Parliament to scrutinize government actions, fostering a balance of power.

5. Providing Stability and Flexibility in Governance

Conventions play a crucial role in providing both stability and flexibility within the British political system. Since they are not legally codified, conventions can evolve to meet changing political and social needs without requiring formal amendments to the constitution. This flexibility is particularly important in the British political system, as it allows for adaptability in governance while maintaining core constitutional principles.

For example, the Fixed-term Parliaments Act 2011 changed the convention of the Prime Minister’s discretion to call general elections. While this law altered the convention, subsequent political developments demonstrated that conventions around early elections and parliamentary confidence votes remain influential. This adaptability highlights the resilience of conventions in preserving constitutional norms in response to evolving political dynamics.

Significance of Conventions in the British Political System

The significance of conventions in the British political system cannot be overstated. Although not legally enforceable, conventions form an integral part of the unwritten constitution, guiding political behavior and upholding constitutional values. Below are some key aspects of their significance:

Upholding Democratic Principles: Conventions, such as those governing the accountability of ministers and parliamentary oversight, ensure that democratic principles are respected, even in the absence of a codified constitution.

Enabling Stability and Predictability: Conventions create a stable framework within which government institutions operate. By providing established rules of behavior, conventions reduce uncertainty and promote consistency in governance.

Allowing for Adaptability: The unwritten and flexible nature of conventions allows them to adapt to changing circumstances. This adaptability is crucial for a dynamic political system like the UK, where new conventions may emerge to address contemporary issues.

Maintaining Political Neutrality of the Monarchy: Conventions surrounding the monarchy have allowed the institution to retain its symbolic significance while delegating political power to elected representatives. This balance preserves public trust in the monarchy and enhances its role as a unifying symbol of the nation.

Conclusion

Conventions are indispensable in the British political system, providing an essential framework for the exercise of political power within an unwritten constitution. They play a critical role in regulating the powers of the monarchy, guiding the behavior of the executive, upholding parliamentary sovereignty, and ensuring the accountability of government officials. Despite their lack of legal force, conventions are respected and adhered to, as they reflect deeply rooted political norms and democratic values. Through their flexibility and adaptability, conventions enable the British political system to respond to new challenges and maintain stability, continuity, and democratic accountability. In essence, conventions act as the invisible glue that holds together the various elements of the British constitution, ensuring that governance aligns with constitutional principles while remaining adaptable to the evolving needs of society.

The British Parliament stands as one of the oldest and most influential legislative bodies in the world, with its roots dating back over 700 years. It operates as a bicameral legislature, comprising the House of Commons and the House of Lords, alongside the monarch as the formal head of state. Together, these components form the core of the United Kingdom’s parliamentary democracy, with Parliament wielding significant power to legislate, scrutinize the government, and represent the interests of citizens. Despite the evolution of political practices over centuries, the British Parliament remains a crucial institution for upholding democratic principles, maintaining checks and balances on the government, and shaping national policy.

Organization of the British Parliament

The British Parliament is structured into three main parts: the House of Commons, the House of Lords, and the Monarch. Each component plays a distinct and complementary role within the parliamentary system, ensuring a balanced and representative approach to governance.

1. The House of Commons

The House of Commons is the primary legislative chamber of the British Parliament, consisting of 650 Members of Parliament (MPs) elected from constituencies across the UK. It is the dominant house in terms of legislative authority and public representation. Members of the House of Commons are elected through a first-past-the-post voting system, where each constituency elects one MP to represent its interests.

The Commons is led by the Speaker of the House, an impartial figure responsible for maintaining order during debates, upholding procedural rules, and ensuring fair representation of all MPs. The Speaker’s role is crucial in preserving the neutrality of the House and enabling constructive debate on legislative matters.

The House of Commons is generally regarded as the more democratic chamber, as its members are directly elected by citizens, providing them with a strong mandate to legislate, debate national issues, and hold the government accountable. The party or coalition with the majority of seats in the Commons typically forms the government, with its leader becoming the Prime Minister.

2. The House of Lords

The House of Lords is the upper chamber of the British Parliament, with members appointed rather than elected. Its membership comprises life peers, hereditary peers, and bishops of the Church of England. Life peers are appointed by the monarch on the advice of the Prime Minister, while a limited number of hereditary peers retain seats through a process of election within their ranks. The House of Lords is chaired by the Lord Speaker, a role similar to the Speaker in the Commons but less politically influential.

The House of Lords acts as a revising chamber that scrutinizes and reviews legislation passed by the House of Commons. Although it cannot veto legislation outright, the Lords can delay bills and propose amendments, serving as a check on the legislative process. The chamber’s role is often described as “complementary” rather than competitive to the Commons, providing expertise, continuity, and depth of analysis on complex issues.

3. The Monarch

The Monarch is the ceremonial head of state and a symbolic part of the British Parliament. While the monarch’s role in Parliament is largely formal and symbolic, they retain specific constitutional responsibilities, such as giving Royal Assent to bills passed by Parliament, which is necessary for them to become law. The monarch’s involvement in parliamentary matters is governed by conventions, ensuring that their influence remains politically neutral and that power resides primarily with elected representatives.

The monarch also performs important ceremonial duties, such as the State Opening of Parliament, during which they deliver the Queen’s Speech (or King’s Speech) outlining the government’s legislative agenda. This speech, however, is prepared by the government and reflects its priorities rather than the monarch’s own views.

Powers of the British Parliament

The British Parliament holds significant powers that enable it to shape national policy, scrutinize government actions, and represent the public. These powers are derived from the principle of parliamentary sovereignty, which establishes Parliament as the supreme legal authority in the United Kingdom. Below are some of the key powers vested in Parliament:

1. Legislative Power

Parliament’s primary power is its legislative authority—the ability to make, amend, and repeal laws. As the supreme legislative body, Parliament can pass laws on any subject, with the authority to override or repeal previous statutes. Both the House of Commons and the House of Lords participate in the legislative process, though the Commons holds the greater influence.

In terms of process, proposed laws, or bills, are introduced and must pass through several stages in both houses, including the First Reading, Second Reading, Committee Stage, Report Stage, and Third Reading. This structured process ensures thorough debate, scrutiny, and the opportunity for amendments. After passing through both chambers, a bill requires Royal Assent from the monarch to become law, although this assent is granted as a formality due to convention.

2. Financial Power

One of the most critical powers of the House of Commons is its control over finance and public expenditure. The Commons has exclusive authority to introduce and approve money bills, including the annual budget, which determines government spending and taxation. This power is central to the democratic principle of no taxation without representation, as elected MPs control the allocation and use of public funds.

The House of Lords cannot amend or reject money bills, ensuring that decisions regarding public finances remain with the directly elected representatives. This financial power gives the Commons a key tool for holding the government accountable, as any failure by the government to secure approval for its budget can lead to a vote of no confidence and potential dissolution of Parliament.

3. Power of Scrutiny and Oversight

Parliament exercises a significant scrutiny role over the executive branch, ensuring that the government remains accountable to elected representatives and, by extension, the public. This is achieved through mechanisms such as Prime Minister’s Questions (PMQs), parliamentary debates, and the work of select committees.

Prime Minister’s Questions (PMQs): Held weekly, PMQs provide MPs with the opportunity to question the Prime Minister on various issues, holding the government directly accountable for its policies and decisions.

Select Committees: Parliament also operates a series of select committees, each tasked with scrutinizing a specific area of government activity, such as health, defense, and foreign affairs. These committees conduct inquiries, summon witnesses, and review government performance, producing reports that can influence policy and public opinion.

The scrutiny power of Parliament is crucial in maintaining a balance of power and preventing abuses of authority, as it ensures the government remains transparent and accountable in its actions.

4. Constitutional Power

Although the UK lacks a single written constitution, Parliament holds significant constitutional power, enabling it to define and alter the country’s constitutional framework. Through statutes and reforms, Parliament can change fundamental aspects of governance, such as voting rights, devolution, and the powers of the judiciary. For instance, the Constitutional Reform Act 2005 created the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom, separating the judicial role from the House of Lords.

Parliament’s constitutional power is derived from the principle of parliamentary sovereignty, which allows it to legislate on any matter. This power enables Parliament to adapt the constitution to the changing needs of society and governance, maintaining the flexibility of the British system.

5. Power to Declare War and Ratify Treaties

Although the executive, led by the Prime Minister, typically holds the power to make decisions regarding war and foreign relations, there is a growing convention that Parliament should have a role in authorizing military action. For example, the House of Commons voted on the decision to go to war in Iraq in 2003 and on the intervention in Syria in 2013. This informal requirement for parliamentary approval in matters of war reflects the public demand for democratic accountability in foreign policy decisions.

Parliament also has a role in ratifying treaties, although this is typically managed by the executive. However, the Constitutional Reform and Governance Act 2010 strengthened Parliament’s oversight by giving the House of Commons the power to delay treaty ratification, enhancing its role in foreign policy.

Functions of the British Parliament

In addition to its powers, the British Parliament performs several key functions essential for democratic governance. These functions contribute to its role as the central institution of accountability and representation in the UK.

1. Law-Making

As the supreme legislative authority, Parliament’s primary function is law-making. It introduces, debates, amends, and passes laws on a wide range of issues affecting society. Through its law-making function, Parliament establishes legal frameworks that address social, economic, and political needs, enabling effective governance.

2. Representation

Parliament performs the critical function of representing the people. MPs in the House of Commons represent the interests of their constituents, voicing concerns, raising issues, and advocating for policies that benefit their constituencies. This function is particularly important in a representative democracy, as it ensures that citizens’ views are considered in the legislative process.

3. Scrutiny and Accountability

A major function of Parliament is to scrutinize government actions and hold it accountable. This involves questioning ministers, investigating policies, and assessing government performance through select committees. The scrutiny function is essential for transparency and checks and balances, preventing the misuse of power by the executive.

4. Financial Control

Through its financial function, Parliament controls government spending and revenue collection, ensuring that public funds are used efficiently and responsibly. By scrutinizing the budget and holding the government accountable for its financial decisions, Parliament upholds fiscal discipline and protects taxpayers’ interests.

5. Conflict Resolution

Parliament also acts as a forum for conflict resolution by providing a platform for debate and compromise on contentious issues. This function allows Parliament to address divisive topics through democratic discussion, promoting social cohesion and preventing political or social conflicts from escalating.

Conclusion

The British Parliament plays a central role in the governance of the United Kingdom, exercising wide-ranging powers and functions that shape public policy, uphold accountability, and represent the people. Its bicameral structure—with the House of Commons, House of Lords, and the monarchy—ensures that Parliament reflects diverse perspectives, enabling effective law-making and democratic representation. Through its legislative, financial, and scrutiny powers, Parliament holds the government accountable and maintains a balance of power, protecting the rights and interests of citizens. The British Parliament’s adaptability and adherence to democratic principles have enabled it to remain a vital institution in the UK’s political system, serving as both the guardian of the constitution and the voice of the people.

Introduction

England, Wales, Scotland, and Northern Ireland make up the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, which is a constitutional monarchy with a parliamentary system of government. The written and unwritten procedures that establish the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland as a political body are referred to as the British constitution. The United Kingdom is often referred to as having an “unwritten” constitution. This is not entirely accurate as it is mostly written but in various documents. However, it has never been codified or compiled into a single document. In this regard, the United Kingdom differs from most other countries with written constitutions.

Salient features of the British Constitution

Although the British Constitution is not a completely codified one, certain rules, acts, conventions, and regulations are considered constitutional documents. These documents determine the working of the country and impart certain features to this ‘unwritten’ constitution. Some of the most significant features are listed in the following sections:

British Constitution is unwritten

As mentioned previously, the British Constitution is not a particular codified document like that which exists in India. However, it is unwritten and is an aggregate of several documents which together constitute the rules of the land. The unwritten character of the British constitution is by far the most important element. There is no documented, accurate, and compact document that can be referred to as the British constitution. The fundamental reason for this is that it is founded on customs and political traditions that are not codified in any text. Historical Documents, Parliamentary Statutes, Judicial Decisions, and Constitutional Characters, such as the Magna Carta (1215), Petition of Rights (1628), Bill of Rights (1689), and Parliamentary Acts of 1911 and 1949, are among the written portions.

It is significant to note the British Constitution is also a mixed Constitution. The British constitution is a mix of monarchical, aristocratic, and democratic values. The institution of monarchy in England is demonstrated through the institution of kingship. The presence of the House of Lords suggests that the institution of kingship is in existence. The administration of England is aristocratic. The House of Commons is a reflection of how a full-fledged democracy works in this country. However, all of these disparate political aspects have been expertly welded together to make a flawless representative democracy.

The British Constitution keeps evolving with time

The British constitution is an example of how things have evolved over time. There was no presence of a constituent assembly to frame the British Constitution like the one that framed the Indian constitution. This nature is due to the fact that it is the result of slow growth and evolution. A particular date of its creation cannot be provided, and no one group of people can claim to be its authors. It has had a continuous evolution for over a thousand years. It has a variety of sources, and its evolution has been influenced by both accidents and high-level designs. The British Constitution is said to be the result of both wisdom and social circumstances. It has had a continuous evolution and reforms for over a thousand years from the Magna Carta to the Bill of Rights 1689 to the Act of Settlement 1701 to the Treaty and Acts of Union of 1706-1707 to Act of Union 1800 to the Parliament Acts 1911 and 1949 to the European Communities Act 1972 to the Human Rights Act 1998 to the House of Lords Act 1999 and to the European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018.

British Constitution is flexible

One of the most obvious features of an unwritten constitution is the flexibility that comes with the uncodified structure, which might be considered a merit and demerit at the same time. A typical example of a flexible constitution is the British constitution. Because no distinction is established between constitutional legislation and ordinary law, it can be passed, changed, and repealed by a simple majority of Parliament. Both are treated the same way. The virtue of adaptation and adjustability has long been associated with the flexibility factor in the British constitution. This trait has allowed it to adapt to changing circumstances. The Indian Constitution, in contrast, is both flexible as well as rigid. However, amendments to the Indian Constitution are approved only after a tedious process.

British Constitution has a unitary character

In contrast to a federal constitution, the British constitution is unitary in character. The British Parliament, which is a sovereign body, has complete control over the administration. It is subservient to the executive organs of the state, which have delegated powers and are accountable to it. There is just one legislature in the United States unlike in the UK. England, Scotland, Wales and the rest of the United Kingdom is composed of administrative, rather than political autonomous units. Instead of adopting a federal model like the United States, the United Kingdom uses a devolutionary system in which political power is gradually decentralised. Devolution differs from federalism in the aspect that unlike federalism, in devolution, regions are not guaranteed constitutional powers.

British Constitution promotes a parliamentary executive

The United Kingdom is governed by a Parliamentary system. All of the King’s powers and authority have been taken away from him. Ministers who belong to the majority party in Parliament and continue in office as long as their party’s trust in them is maintained are the true functionaries. Acts and policies of the Prime Minister and his ministers are accountable to the legislature. The executive and legislative branches of government are not separated in this system, as they are in the Presidential form of government.

British Constitution promotes a Sovereign Parliament

Parliamentary sovereignty is a key aspect of the British constitution. Parliamentary sovereignty refers to the fact that parliament is superior to the executive and judicial spheres of the government and so has the power to adopt or repeal any law. Parliament is the sole legislative body in the country with unrestricted legislative powers, allowing it to enact, amend, and abolish any law it sees fit. There is no purer way for the courts to call into question the legality of laws approved by the British Parliament than through the courts. The parliament can even alter the constitution on its own authority as if it were ordinary law. It has the power to make what is legal, illegal and legalise what is illegal. Parliament became sovereign as a result of a series of power battles involving the king, the church, the courts, and the people throughout history.

British Constitution upholds the Rule of Law

Modern legal systems, like the United Kingdom’s, see the rule of law as a fundamental premise. It has been referred to as “as important in a free society as the democratic franchise,” and even “the ultimate governing principle on which the constitution is founded.” This prevents the Executive from acting arbitrarily. It has evolved to only work in tandem with the equal application of the law to all citizens (‘equality before the law,’) and to maintain the legal philosophy of parliamentary sovereignty within the framework of the constitutional monarchy. The main function of the judiciary is to uphold the rule of law. The principles of the rule of law are:

- In the eyes of the law, everyone is equal, regardless of their position or rank.

- This theory emphasises that the law, not any individual, is supreme.

- Without a fair and adequate trial by a competent court of law, no one can be detained or imprisoned. A person cannot be punished or deprived of his or her life, liberty, or property unless there has been a specific breach of law proven in a regular court of law through a regular procedure.

British Constitution prescribes an Independent Judiciary

The Rule of Law in the United Kingdom is protected by the fact that judges can only be removed from office for significant misconduct and only after a procedure that requires the approval of both Houses of Parliament. As a result, the judges are free to make their decisions without fear or favour. The same approach has been taken in India, where judicial independence is regarded as an unambiguous component of the Constitution.

Sources of the British Constitution

The United Kingdom’s constitution is made up of character and statute, as well as judicial decisions, common law, precedents, customs, and traditions. There are thousands of documents, not just one. The British Constitution can be found in a variety of places. The UK constitution’s sources include both law and other less formal documents that have no legal force. Acts of Parliament, court cases, and conventions in the way the government, Parliament, and the monarch act are the key sources of constitutional law.

Historical constitutional documents

The evolution of UK constitutional legislation from the establishment of England, Wales, Scotland, and Ireland to the current day is the subject of the history of the UK constitution. The history of the United Kingdom constitution dates back to a time before the four nations of England, Scotland, Wales, and Ireland were fully created, despite the fact that it was formally established in 1800. Great charters and treaties, which define and limit the Crown’s power and citizens’ rights, are the earliest source of the British Constitution. Some of the historical constitutional documents are mentioned hereunder:

Magna Carta (1215)

The Magna Carta, or “Great Charter,” was undoubtedly the most influential historical document among other influences, on the long historical process that led to the rule of constitutional law in the UK today.

After King John of England broke a number of old rules and practises that had controlled England, his subjects forced him to sign the Magna Carta, which enumerates what would later be known as human rights. The right of the church to be free from government intervention, the rights of all free citizens to own and inherit property and be protected from exorbitant taxes, and the right of widows who held property not to remarry were among them. It also included rules prohibiting bribery and official corruption.

Magna Carta’s role as a source of liberty has long been recognised. One of the fundamental stipulations of the 1215 Charter was that no one should be imprisoned without first going through the legal system. This also introduced the concept of a jury trial. ‘No free man shall be seized, imprisoned, exiled, or in any manner ruined… except by the lawful judgement of his peers or by the law of the realm,’ according to Clause 39 of the 1215 Charter. This successfully established the rule of law notion, which protects people from arbitrary punishment.

Petition of Right (1628)

The Petition of Right, which was passed on June 7, 1628, is an English constitutional instrument that establishes explicit individual safeguards against the state and is said to be on par with the Magna Carta and the Bill of Rights of 1689. It was part of a larger dispute between Parliament and the Stuart monarchy that culminated in the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, which lasted from 1638 to 1651 and were finally settled in the Glorious Revolution of 1688. King Charles-I surrendered to the Petition of Right (1628), which featured protests against taxes without Parliament’s authorisation, unjust detention, and military grievances.

Bill of Rights (1689)

It is an original Act of the English Parliament that has remained in Parliament’s possession since its inception. The Bill established the ideals of frequent parliaments, free elections, and freedom of speech in Parliament, which is now known as Parliamentary Privilege.

All of the Bill of Rights’ main principles are still in effect today, and the Bill of Rights is frequently mentioned in judicial proceedings in the United Kingdom and Commonwealth countries. It occupies a central position in a larger national historical narrative of papers that established Parliament’s rights and established universal civil liberties, beginning with the Magna Carta in 1215.

Act of Settlement (1701)

The Act of Settlement of 1701 was enacted to ensure the Protestant succession to the crown and to enhance the guarantees that a parliamentary system of government would be maintained.

Acts of the UK Parliament

An Act of the UK Parliament is an action or a step taken by the Parliament that enact new legislation or modifies existing legislation. An Act is a Bill that has received Royal Assent from the Monarch after being approved by both the House of Commons and the House of Lords. Acts of Parliament, when taken collectively, make up what is known in the United Kingdom as Statute Law. The UK constitution is based on a number of articles of fundamental law. Devolution agreements; the right to vote and elections; the protection of human rights; the prohibition of discrimination; the existence of the Supreme Court; and much more are all covered by these laws. Despite their constitutional significance, there is no obvious formal distinction between these statutes and regular laws.

These acts of influential value which have a constitutional significance, include the Act of Habeas Corpus (1679), the Act of Settlement (1701), the Reform Acts of 1832, 1867, 1884, 1918, and 1928, the Parliament Acts of 1911 and 1949, and the West Minister’s Statute of 1931, among others.

The Habeas Corpus Act safeguards an essential right against detention. A person who is imprisoned without legal basis can be released under the Habeas Corpus Act. Previously the Act of Settlement dealt with the succession of the authority, according to which, The King must be a Protestant. The right to vote (franchise) and Parliamentary representation are determined by the different Reform Acts. the Reforms Act is the main basis for election and parliamentary representation issues till date. The House of Lords’ powers is governed by the Parliament Act of 1911, as revised in 1949. The Statute of Westminster establishes the Dominion status and their connection with the home country, the United Kingdom.

The most essential source of the British Constitution is the statute law as the Parliament is a sovereign body and it makes legislations. As a result, any law passed by Parliament (a Statute Law) supersedes all other constitutional sources. In the United Kingdom, the Constitution is generally modified through Statute Law. The Human Rights Act of 1998 and the Devolution Acts of 1998 are two notable instances. As a result of Parliamentary Sovereignty, there is no way to overturn Statute Law other than for Parliament to repeal it. In Common Law, Statute Law is utilised to resolve inconsistencies or areas of ambiguity.

Common Law

The third branch of law is common law. Common law, often known as case law or precedent, is a body of law created by judges, courts, and other tribunals. It is one of the many sources of the unwritten constitution of the United Kingdom. It will be mentioned in rulings that decide particular cases, but it may also have precedential implications for future cases. The majority of the rights that the British people have today are the result of legal battles. In England, judicial decisions have established the right to personal liberty, the right to public assembly, the right to freedom of speech, and so on. It is distinguished from and is on an equal footing with statutes, which are enacted through the legislative process, and regulations, which are enacted by the executive branch.

Conventions

Constitutional conventions play an important role in the uncodified British constitution. Some regulations are followed by the various constituent components despite the fact that they are not written in any legally binding instrument. There are often underlying enforcing principles that are not codified. A convention is a rule referring to strict behaviour that does not have the authority of law. Certainly, repeated practice can become formalised as a norm of conduct and, in that sense, become customs. Conventions are however obeyed by the people because they are extremely beneficial to the government’s smooth operation. Written conventions include ‘the Cabinet Manual‘ and ‘the Ministerial Code.’ Conventions have traditionally not been put down in official papers. However, in recent decades, accounts of them have become increasingly common in writings published by institutions such as the UK government. The courts’ approach to constitutional conventions is unquestionably distinct from their approach to legal standards. Conventions are beyond the scope of the courts’ authority to rule on.

Works of Authority

Books created by constitutional theorists that are regarded as authoritative guides on the UK’s uncodified constitution are known as works of authority on the UK constitution. On England’s constitutional law, legal authorities and notable jurists have written opinions. Arson’s Law and Customs of Constitution, May’s Parliamentary Practice, and Dicey’s Law of Constitution are considered authoritative commentaries on English constitutional law and practice. Because the United Kingdom lacks a codified constitution, these documents serve as guides to the country’s regulations and practises. Acts of Parliament can either adopt or override them.

Institutions

The Parliament

Over the course of three centuries, the British Parliament has evolved. Because there is no written constitution in the United Kingdom, the Parliament can be said to be the sole entity that exercises sovereign powers and has no boundaries. The British Parliament is bicameral, meaning it consists of two houses or chambers: the House of Lords (whose strength is not fixed) and the House of Commons (whose strength is fixed) (strength fixed at 650 members). Hereditary members make up the House of Lords.

The House of Lords

The House of Lords is the United Kingdom’s bi-cameral (two-chamber) parliament’s second chamber, or upper house. The House of Lords, along with the House of Commons and the Crown, make up the UK Parliament. Members of the house are divided into four categories: life peers, law lords, bishops, and elected hereditary peers. The House of Lords has the power to propose and pass amendments. Its powers, however, are restricted; if it does not agree with a piece of legislation, it can only postpone its enactment for up to a year. Following that, there are rules in place to ensure that the views of the House of Commons and the current government are carried out.

The House of Commons

The Speaker of the House of Commons presides over the lower chamber. The number of members fluctuates slightly over time as the population changes. In current practice, the Prime Minister leads the government and is always a member of the House of Commons majority party or a coalition. Although members of the House of Lords have served as Cabinet ministers, the Cabinet is usually made up of House of Commons members who belong to the majority party. Despite being the head of government and a member of Parliament, the Prime Minister is no longer the leader of the House of Commons. The Speaker of the House of Commons is the majority party’s chief spokesman.

Amendments and changes to the British Constitution

An amendment is a change to the wording of a Bill or a motion offered by a member of the House of Commons or the House of Lords. The term “consideration of amendments” refers to the final step of a bill’s development. When a Bill is passed by one House and then amended by the other House, the first House must consider the amendments.

The Executive