Economics – 1st Year

Paper – I (PYQs Soln.)

Unit I

Language/भाषा

CONSUMER’S EQUILIBRIUM

The term ‘equilibrium’ is frequently used in economic analysis. Equilibrium means a state of rest or a position of no change. It refers to a position of rest, which provides the maximum benefit or gain under a given situation. A consumer is said to be in equilibrium, when he does not intend to change his level of consumption, i.e., when he derives maximum satisfaction.

Consumer’s Equilibrium refers to the situation when a consumer is having maximum satisfaction with limited income and has no tendency to change his way of existing expenditure.

The consumer has to pay a price for each unit of the commodity. So, he cannot buy or consume unlimited quantity. As per the Law of DMU, utility derived from each successive unit goes on decreasing. At the same time, his income also decreases with purchase of more and more units of a commodity. So, a rational consumer aims to balance his expenditure in such a manner, so that he gets maximum satisfaction with minimum expenditure. When he does so, he is said to be in equilibrium. After reaching the point of equilibrium, there is no further incentive to make any change in the quantity of the commodity purchased.

Consumer’s equilibrium can be discussed under two different situations:

- Consumer spends his entire income on a Single Commodity

- Consumer spends his entire income on Two Commodities

Consumer’s Equilibrium in case of Single Commodity

The Law of DMU can be used to explain consumer’s equilibrium in case of a single commodity. Therefore, all the assumptions of Law of DMU are taken as assumptions of consumer’s equilibrium in case of single commodity.

A consumer purchasing a single commodity will be at equilibrium, when he is buying such a quantity of that commodity, which gives him maximum satisfaction. The number of units to be consumed of the given commodity by a consumer depends on 2 factors:

- Price of the given commodity;

- Expected utility (Marginal utility) from each successive unit.

To determine the equilibrium point, consumer compares the price (or cost) of the given commodity with its utility (satisfaction or benefit). Being a rational consumer, he will be at equilibrium when marginal utility is equal to price paid for the commodity.

We know, marginal utility is expressed in utils and price is expressed in terms of money. However, marginal utility and price can be effectively compared only when both are stated in the same units. Therefore, marginal utility in utils is expressed in terms of money.

Marginal Utility in terms of Money = \(\frac{Marginal\;Utility\;in\;utils}{Marginal\;Utility\;of\;one\;rupee\;(MU_M)}\)

MU of one rupee is the extra utility obtained when an additional rupee is spent on other goods. As utility is a subjective concept and differs from person to person, it is assumed that a consumer himself defines the MU of one rupee, in terms of satisfaction from bundle of goods.

Equilibrium Condition

Consumer in consumption of single commodity (say, x) will be at equilibrium when:

Marginal Utility (\(MU_x\)) is equal to Price (\(P_x\)) paid for the commodity; i.e. \(MU_x = P_x\).

- If MU > P, then consumer is not at equilibrium and he goes on buying because benefit is greater than cost. As he buys more, MU falls because of operation of the law of diminishing marginal utility. When MU becomes equal to price, consumer gets the maximum benefits and is in equilibrium.

- Similarly, when (\(MU_x < P_x\)) then also consumer is not at equilibrium as he will have to reduce consumption of commodity x to raise his total satisfaction till MU becomes equal to price.

Note: In addition to condition of “MU Price”, one more condition is needed to attain consumer’s equilibrium: “MU falls as consumption increases”. If MU does not fall, then consumer will go on consuming the commodity and hence will never attain the equilibrium position. However, this second condition is always implied because of operation of Law of DMU.

Let us now determine the consumer’s equilibrium if the consumer spends his entire income on single commodity. Suppose, the consumer wants to buy a good (say, x), which is priced at 10 per unit. Further suppose that marginal utility derived from each successive unit (in utils and in) is determined and is given in Table 1.1 (For sake of simplicity, it is assumed that 1 util1, i.e. (\(MU_M = ₹1\)).

Table 1.1 Consumer’s Equilibrium in Case of Single Commodity

In Fig. 1.1, \(M_x\) curve slopes downwards, indicating that the marginal utility falls with successive consumption of commodity x due to operation of Law of DMU. Price ( \(P_x\) ) is a horizontal and straight price line as price is fixed at 10 per unit.

From the given schedule and diagram, it is clear that the consumer will be at equilibrium at point ‘E’, when he consumes 3 units of commodity x, because at point E, \(MU_x=P_x\)

- He will not consume 4 units of x as MU of 4 is less than price paid of ₹10.

- Similarly, he will not consume 2 units of x as MU of 16 is more than the price paid.

So, it can be concluded that a consumer in consumption of single commodity (say, x) will be at equilibrium when marginal utility from the commodity (\(MU_x\)) is equal to price (\(P_x\)) paid for the commodity.

The equilibrium condition can also be expressed as:

$$\frac{MU_x}{MU_M}=P_x\;or\;\frac{MU_x}{P_x}=MU_M$$

Consumer’s Equilibrium in case of Two Commodities

The Law of DMU applies in case of either one commodity or one use of a commodity. However, in real life, a consumer normally consumes more than one commodity. In such a situation, ‘Law of Equi-Marginal Utility’ helps in optimum allocation of his income.

Law of Equi-marginal utility is also known as: (i) Law of Substitution; (ii) Law of maximum satisfaction; (iii) Gossen’s Second Law.

As law of Equi-marginal utility is based on Law of DMU, all assumptions of the latter also applies to the former. Let us now discuss equilibrium of consumer by taking two goods: ‘x’ and ‘y’. The same analysis can be extended for any number of goods. In case of consumer equilibrium under single commodity, we assumed that the entire income was spent on a single commodity. Now, consumer wants to allocate his money income between the two goods to attain the equilibrium position.

According to the law of Equi-marginal utility, a consumer gets maximum satisfaction, when ratios of MU of two commodities and their respective prices are equal and MU falls as consumption increases.

It means, there are two necessary conditions to attain Consumer’s Equilibrium in case of Two Commodities:

1. The ratio of Marginal Utility to Price is same in case of both the goods.

- We know, a consumer in consumption of single commodity (say, x) is at equilibrium

When = \(\frac{MU_x}{P_x}=MU_M\) … (1)

- Similarly, consumer consuming another commodity (say, y) will be at equilibrium

When \(\frac{MU_y}{P_y}=MU_M\) ….. (2)

Equating 1 and 2, we get: \(\frac{MU_x}{P_x}=\frac{MU_y}{P_y}=MU_M\)

As marginal utility of money (\(MU_M\)) be constant, the above equilibrium condition can be restated as:

$$\frac{MU_x}{P_x} = \frac{MU_y}{P_y} = \frac{P_x}{P_y}$$

2. MU falls as consumption increases: The second condition needed to attain consumer’s equilibrium is that MU of a commodity must fall as more of it is consumed. If MU does not fall as consumption increases, the consumer will end up buying only one good which is unrealistic and consumer will never reach the equilibrium position.

Finally, it can be concluded that a consumer in consumption of two commodities will be at equilibrium when he spends his limited income in such a way that the ratios of marginal utilities of two commodities and their respective prices are equal and MU falls as consumption increases.

Explanation with the help of an Example

Let us now discuss the law of equi-marginal utility with the help of a numerical example. Suppose, total money income of the consumer is 5, which he wishes to spend on two commodities: ‘x’ and ‘y’. Both these commodities are priced at 1 per unit. So, consumer can buy maximum 5 units of ‘x’ or 5 units of ‘y’. In Table 2.4, we have shown the marginal utility which the consumer derives from various units of ‘x’ and ‘y’.

Table 1.2 Consumer’s Equilibrium in Case of Two Commodities

| Units | MU of commodity ‘x’ (in utils) | MU of commodity ‘y’ (in utils) |

|---|---|---|

| 5 | 5 | 3 |

| 4 | 7 | 5 |

| 3 | 12 | 8 |

| 2 | 14 | 12 |

| 1 | 20 | 16 |

From Table 1.2, it is obvious that the consumer will spend the first rupee on commodity ‘x’, which will provide him utility of 20 utils. The second rupee will be spent on commodity ‘y’ to get utility of 16 utils. To reach the equilibrium, consumer should purchase that combination of both the goods, when:

- MU of last rupee spent on each commodity is same; and

- MU falls as consumption increases.

It happens when consumer buys 3 units of ‘x’ and 2 units of ‘y’ because:

- MU from last rupee (i.e. 5th rupee) spent on commodity y gives the same satisfaction of 12 utils as given by last rupee (i.e. 4th rupee) spent on commodity x; and

- MU of each commodity falls as consumption increases. The total satisfaction of 74 utils will be obtained when consumer buys 3 units of ‘x’ and 2 units of ‘y’. It reflects the state of consumer’s equilibrium. If the consumer spends his income in any other order, total satisfaction will be less than 74 utils.

Limitation of Utility Analysis

In the utility analysis, it is assumed that utility is cardinally measurable, i.e., it can be expressed in exact unit. However, utility is a feeling of mind and there cannot be a standard measure of what a person feels. So, utility cannot be expressed in figures. There are other limitations too. But, their discussion is beyond the scope.

ORDINAL UTILITY APPROACH (INDIFFERENCE CURVE OR HICKSIAN ANALYSIS)

The real elaboration of the Indifference Curves was made by J. R. Hicks and R. G. D. Allen, popularly known as Hicks and Allen. In 1934, they wrote an article, ‘A Reconstruction of the Theory of Value’, presenting the Indifference Curve Analysis.

Modern economists disregarded the concept of ‘cardinal measure of utility’. They were of the opinion that utility is a psychological phenomenon and it is next to impossible to measure the utility in absolute terms. According to them, a consumer can rank various combinations of goods and services in order of his preference.

For example, if a consumer consumes two goods, Apples and Bananas, then he can indicate:

- Whether he prefers apple over banana; or

- Whether he prefers banana over apple; or

- Whether he is indifferent between apples and bananas, i.e. both are equally preferable and both of them give him same level of satisfaction.

This approach does not use cardinal values like 1, 2, 3, 4, etc. Rather, it makes use of ordinall numbers like 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th, etc. which can be used only for ranking. It means, if the consumer likes apple more than banana, then he will give 1st rank to apple and 2nd rank to banana. Such a method of ranking the preferences is known as ‘ordinal utility approach’. Ordinal utility is the utility expressed in ranks.

Before we proceed to determine the consumer’s equilibrium through this approach, let us understand some useful concepts related to Indifference Curve Analysis.

Meaning of indifference Curve

When a consumer consumes various goods and services, then there are some combinations, which give him exactly the same total satisfaction. The graphical representation of such combinations is termed as indifference curve.

Indifference curve refers to the graphical representation of various alternative combinations of bundles of two goods among which the consumer is indifferent.

Alternately, indifference curve is a locus of points that show such combinations of two commodities which give the consumer same satisfaction. Let us understand this with the help of following indifference schedule, which shows all the combinations giving equal satisfaction to the consumer.

Table 1.3 Indifference Schedule

| Combination of Apples and Bananas | Apples (A) | Bananas (B) |

|---|---|---|

| P | 1 | 15 |

| Q | 2 | 10 |

| R | 3 | 6 |

| S | 4 | 3 |

| T | 5 | 1 |

As seen in the schedule, consumer is indifferent between five combinations of apple and banana. Combination ‘P’ (1A + 15B) gives the same utility as (2A + 10B), (3A + 6B) and so on. When these combinations are represented graphically and joined together, we get an indifference curve ‘IC₁’ as shown in Fig. 2.4.

In the diagram, apples are measured along the X-axis and bananas on the Y-axis. All points (P, QR. S and T) on the curve show different combinations of apples and bananas. These points are joined with the help of a smooth curve, known as indifference curve (IC₁’). An indifference curve is the locus of all the points, representing different combinations, that are equally satisfactory to the consumer.

Every point on IC₁ represents an equal amount of satisfaction to the consumer. So, the consumer is said to be indifferent between the combinations located on Indifference Curve IC₁.

The combinations P, Q, R, S and T give equal satisfaction to the consumer and therefore he is indifferent among them. These combinations are together known as ‘Indifference Set’.

Monotonic Preferences

Monotonic preference means that a rational consumer always prefers more of a commodity as it offers him a higher level of satisfaction. In simple words, monotonic preferences implies that as consumption increases total utility also increases. For instance, a consumer’s preferences are monotonic only when between any two bundles, he prefers the bundle which has more of at least one of the goods and no less of the other good as compared to the other bundle.

Example: Consider 2 goods: Apples (A) and Bananas (B).

- Suppose two different bundles are: 1st: (10A, 10B); and 2nd: (7A, 7B). Consumer’s preference of 1st bundle as compared to 2nd bundle will be called monotonic preference as 1st bundle contains more of both apples and bananas.

- If 2 bundles are: 1st: (10A, 7B); 2nd: (9A, 7B).

Consumer’s preference of 1 bundle as compared to 2nd bundle will be called monotonic preference as 1ª bundle contains more of apples, although bananas are same.

Indifference Map

Indifference Map refers to the family of indifference curves that represent consumer preferences over all the bundles of the two goods.

An indifference curve represents all the combinations, which provide same level of satisfaction. However, every higher or lower level of satisfaction can be shown on different indifference curves. It means, infinite number of indifference curves can be drawn.

In Fig. 1.3, IC₁ represents the lowest satisfaction, IC₁ shows satisfaction more than that of IC₁ and the highest level of satisfaction is depicted by indifference curve IC₁ However, each indifference curve shows the same level of satisfaction individually.

It must be noted that ‘Higher Indifference curves represent higher levels of satisfaction’ as higher indifference curve represents larger bundle of goods, which means more utility because of monotonic preference.

Marginal Rate of Substitution (MRS)

MRS refers to the rate at which the commodities can be substituted with each other, so that total satisfaction of the consumer remains the same. For example, in the example of apples (A) and bananas (B), MRS of ‘A’ for ‘B’, will be number of units of ‘B’, that the consumer is willing to sacrifice for an additional unit of A’ so as to maintain the same level of satisfaction.

\(MRS_{AB}=\frac{Units\;of\;Bananas(B)\;willing\;to\;Sacrifice}{Units\;of\;Apples(A)\;willing\;to\;Gain}\)

\(MRS_{AB}=\frac{ΔB}{ΔA}\)

\(MRS_{AB}\) is the rate at which a consumer is willing to give up Bananas for one more unit of Apple. It means, MRS measures the slope of indifference curve.

It must be noted that in mathematical terms, MRS should always be negative as numerator (units to be sacrificed) will always have negative value. However, for analysis, absolute value of MRS is always considered.

The concept of MRSAB is explained through Table 1.4 and Fig. 1.4.

Table 1.4 MRS between Apple and Banana

| Combination | Apples (A) | Bananas (B) | MRS_AB |

|---|---|---|---|

| P | 1 | 15 | — |

| Q | 2 | 10 | 5B : 1A |

| R | 3 | 6 | 4B : 1A |

| S | 4 | 3 | 3B : 1A |

| T | 5 | 1 | 2B : 1A |

As seen in the given schedule and diagram, when consumer moves from P to Q, he sacrifices 5 bananas for 1 apple. Thus, MRSAB comes out to be 5:1. Similarly, from Q to R, \(MRS_{AB}\) is 4:1. In combination T, the sacrifice falls to 2 bananas for 1 apple. In other words, the MRS of apples for bananas is diminishing.

Why MRS diminishes?

MRS falls because of the law of diminishing marginal utility. In the given example of apples and bananas, Combination ‘P’ has only 1 apple and, therefore, apple is relatively more important than bananas. Due to this, the consumer is willing to give up more bananas for an additional apple. But as he consumes more and more of apples, his marginal utility from apples keeps on declining. As a result, he is willing to give up less and less of bananas for each additional apple.

Assumptions of Indifference Curve

The various assumptions of indifference curve are:

- Two commodities: It is assumed that the consumer has a fixed amount of money, whole of which is to be spent on the two goods, given constant prices of both the goods.

- Non Satiety: It is assumed that the consumer has not reached the point of saturation. Consumer always prefer more of both commodities, i.e. he always tries to move to a higher indifference curve to get higher and higher satisfaction.

- Ordinal Utility: Consumer can rank his preferences on the basis of the satisfaction from each bundle of goods.

- Diminishing marginal rate of substitution: Indifference curve analysis assumes diminishing marginal rate of substitution. Due to this assumption, an indifference curve is convex to the origin.

- Rational Consumer: The consumer is assumed to behave in a rational manner, i.e. he aims to maximise his total satisfaction.

Properties of Indifference Curve

- Indifference curves are always convex to the origin: An indifference curve is convex to the origin because of diminishing MRS. MRS declines continuously because of the law of diminishing marginal utility. As seen in Table 1.4, when the consumer consumes more and more of apples, his marginal utility from apples keeps on declining and he is willing to give up less and less of bananas for each apple. Therefore, indifference curves are convex to the origin (see Fig. 1.4). It must be noted that MRS indicates the slope of indifference curve.

- Indifference curve slope downwards: It implies that as a consumer consumes more of one good, he must consume less of the other good. It happens because if the consumer decides to have more units of one good (say apples), he will have to reduce the number of units of another good (say bananas), so that total satisfaction remains the same.

- Higher Indifference curves represent higher levels of satisfaction: Higher indifference curve represents large bundle of goods, which means more utility because of monotonic preference. Consider point ‘ A’ on IC₁ and point ‘B’ on \(IC_2\) in Fig. 1.3. At ‘A’, consumer gets the combination (OR, OP) of the two commodities x and y. At ‘B’, consumer gets the combination (OS, OP). As OS > OR the consumer gets more satisfaction at \(IC_2\).

4. Indifference curves can never intersect each other: As two indifference curves cannot represent the same level of satisfaction, they cannot intersect each other. It means, only one indifference curve will pass through a given point on an indifference map. In Fig. 1.5, satisfaction from point A and from B on IC₁ will be the same. Similarly, points A and C on IC₂ also give the same level of satisfaction. It means, points B and C should also give the same level of satisfaction. However, this is not possible, as B and C lie on two different indifference curves, \(IC_1\) and \(IC_2\) respectively and represent different levels of satisfaction. Therefore, two indifference curves cannot intersect each other.

An Indifference Curve can never touch X-axis or Y-axis

- The Indifference Curve analysis assumes consumption of two goods, ie. two goods are always consumed. If indifference curve touches Y-axis, it would mean that consumption of commodity on the X-axis is zero.

- Similarly, if indifference curve touches X-axis, it would mean that consumption of commodity on the Y-axis is zero.

So, an indifference curve can never touch any of the axes.

CONSUMER’S EQUILIBRIUM BY INDIFFERENCE CURVE ANALYSIS

Consumer equilibrium refers to a situation, in which a consumer derives maximum satisfaction, with no intention to change it and subject to given prices and his given income. The point of maximum satisfaction is achieved by studying indifference map and budget line together.

On an indifference map, higher indifference curve represents a higher level of satisfaction than any lower indifference curve. So, a consumer always tries to remain at the highest possible indifference curve, subject to his budget constraint.

Conditions of Consumer’s Equilibrium

The consumer’s equilibrium under the indifference curve theory must meet the following two conditions:

(i) \(MRS_{xy}\)= Ratio of prices or \(\frac{P_x}{P_y}\)

Let the two goods be X and Y. The first condition is that \(MRS_{xy}\) = \(\frac{P_x}{P_y}\)

- If \(MRS_{xy}\) > \(\frac{P_x}{P_y}\), it means that to obtain one more unit of X, Py the consumer is willing to sacrifice more units of Y as compared to what is required in the market. It induces the consumer to buy more of X. As a result, MRS falls and continue to fall till it becomes equal to the ratio of prices and the equilibrium is established.

- If \(MRS_{xy}\) < \(\frac{P_x}{P_y}\), it means that Py to obtain one more unit of X, the consumer is willing to sacrifice less units of Y as compared to what is required in the market. It induces the consumer to buy less of X and more of Y. As a result, MRS rises till it becomes equal to the ratio of prices and the equilibrium is established.

(ii) MRS continuously falls. The second condition for consumer’s equilibrium is that MRS must be diminishing at the point of equilibrium, ie. the indifference curve must be convex to the origin at the point of equilibrium. Unless MRS continuously falls, the equilibrium cannot be established.

Thus, both the conditions need to be fulfilled for a consumer to be in a equilibrium.

Let us now understand this with the help of a diagram:

In Fig. 1.6, \(IC_1\), \(IC_2\) and \(IC_3\) are the three indifference curves and AB is the budget line. With the constraint of budget line, the highest indifference curve, which a consumer can reach, is \(IC_2\). The budget line is tangent to indifference curve \(IC_2\) at point ‘E’. This is the point of consumer equilibrium, where the consumer purchases OM quantity of commodity ‘X’ and ON quantity of commodity ‘Y’.

All other points on the budget line to the left or right of point ‘E’ will lie on lower indifference curves and thus indicate a lower level of satisfaction. As budget line can be tangent to

one and only one indifference curve, consumer maximizes his satisfaction at point E, when both the conditions of consumer’s equilibrium are satisfied:

(1) MRS = Ratio of prices \(\frac{P_x}{P_y}\): At tangency point E, the absolute value of the slope of the indifference curve (MRS between X and Y) and that of the budget line (price ratio) are same. Equilibrium cannot be established at any other point as \(MRS_{xy}\) > \(\frac{P_x}{P_y}\) at all points to the left of point E and \(MRS_{xy}\) < \(\frac{P_x}{P_y}\) at all points to the right of point E. So, equilibrium is established at point E, when \(MRS_{xy}\) = \(\frac{P_x}{P_y}\)

(ii) MRS continuously falls: The second condition is also satisfied at point E as MRS is diminishing at point E, i.e. \(IC_2\) is convex to the origin at point E.

Cardinal Utility Vs Ordinal Utility

- Under cardinal utility approach, it is assumed that utility can be measured in cardinal terms, such as 1, 2, 3, etc. However, according to ordinal utility approach, utility is a subjective concept, which cannot be measured and we can just rank the scale of preferences.

- Under cardinal approach, the term “util” was developed as a unit to measure utility, whereas, no such unit of measurement was developed under ordinal approach.

- Example: Suppose a person consumes apple and banana.

According to cardinal approach, the consumer can assign utils to both the commodities, say, 20 utils to apple and 15 utils to banana. It signifies that apple offers 5 more utils than banana.

According to ordinal approach, the consumer cannot express the satisfaction in exact terms. It means, if the consumer likes apple more than banana, then he will give 1st rank to apple and 2nd rank to banana.

The subject matter of economics has been studied under two broad branches:

- Microeconomics (Price Theory)

- Macroeconomics (Income Theory)

These two concepts have become of general use in economics. Let us discuss these concepts in detail.

Microeconomics

Adam Smith is considered to be the founder of the field of microeconomics. The term ‘micro’ has been derived from Greek word ‘mikros’ which means ‘small’. Microeconomics deals with analysis of behaviour and economic actions of small and individual units of the economy, like a particular consumer, a firm or a small group of individual units. The concept of microeconomics is very important as it supplies the foundation for most of our understanding of the functioning of an economy.

Microeconomics is that part of economic theory, which studies the behaviour of individual units of an economy. For example, Individual income, individual output, price of a commodity. etc. Its main tools are Demand and Supply.

Macroeconomics

The term ‘macro has been derived from the Greek word ‘makros’ which means ‘large’. So, macroeconomics deals with overall performance of the economy. It is concerned with study of problems of the economy like inflation, unemployment, poverty, etc.

Macroeconomics is that part of economic theory which studies the behaviour of aggregates of the economy as a whole. For example, National income, aggregate output, aggregate consumption, etc. Its main tools are Aggregate Demand and Aggregate Supply.

Micro Vs Macro

- In Microeconomics, the letter T’ stands for Individuals’, i.e. it studies the economic behaviour of individuals.

- In Macroeconomics, the letter ‘A’ stands for ‘Aggregates’, ie. it studies the economy as a whole.

Let us discuss the detailed differences between the two branches of economics.

Difference between Microeconomics and Macroeconomics

Interdependence of Microeconomics and Macroeconomics

Economics is a single subject and the analysis of an economy cannot be split into two watertight compartments. It means, microeconomics and macroeconomics are not independent of each other and there is much common ground between the two. It means, both microeconomics and macroeconomics are interdependent.

Let us elaborate their interdependence with the help of some examples:

Microeconomics depends on Macroeconomics

- Law of demand came into existence from the analysis of the behaviour of a group (aggregate) of people.

- Price of a commodity is influenced by the general price level prevailing in the economy.

Macroeconomics depends on Microeconomics

- National income of a country is nothing but the sum total of incomes of individual units of the country.

- Aggregate demand depends on demand of individual households of the economy.

Micro-Macro Paradoxes

Paradox is a seemingly absurd or contradictory statement, though, often a true statement. Sometimes, there are paradoxes seen in Micro and Macro activities. It means, an act which is beneficial for an individual, may prove to be harmful for the economy as a whole.

Example: If an individual saves, his family will be benefitted, but if the whole economy starts saving, it will result in contraction of demand, output, employment and income. As a result, the whole economy will suffer.

Which is more Important Microeconomics or Macroeconomics?

Both, microeconomics and macroeconomics have a place of their own and none of them can be dispensed with. Microeconomics concentrates on the working of the individual components and macroeconomics studies the economy in general. While the former is concerned with structures of the aggregates, the latter is concerned with the aggregates themselves. So, both the approaches are supplementary to each other. The superiority of one approach over the other cannot be claimed.

Need for a Separate Theory of Macroeconomics

Microeconomics failed to study the aggregates of the economy as a whole. As a result, there was a need for a separate theory, which could explain the working of the economy. Macroeconomics helps to understand the working of an economic system as well as to explain the various macroeconomic paradoxes.

An indifference curve is a fundamental concept in microeconomics used to analyze consumer preferences. It represents all combinations of two goods that provide a consumer with the same level of satisfaction or utility. The shape, slope, and behavior of indifference curves help economists understand how consumers make choices based on their preferences. Below, the key properties of indifference curves and the possibility of their parallelism are discussed in detail.

1. Downward Sloping Nature

Indifference curves are downward sloping because, to maintain the same level of satisfaction, a consumer must give up some quantity of one good to gain more of another. For instance, if a consumer has two goods, X and Y, an increase in X necessitates a decrease in Y to keep utility constant. This negative slope reflects the trade-off in consumption and is a direct result of the principle of diminishing marginal utility.

2. Convexity to the Origin

Indifference curves are generally convex to the origin, which means they bow inward. This convex shape is explained by the diminishing marginal rate of substitution (MRS), which implies that as a consumer substitutes one good for another, the amount of the good given up decreases progressively. For example, if a consumer substitutes good X for good Y, they are willing to sacrifice less and less of Y for each additional unit of X as X becomes abundant relative to Y.

3. Higher Curves Indicate Higher Utility

An indifference curve that lies farther from the origin represents a higher level of satisfaction than one closer to the origin. This is because a higher curve contains combinations of goods with greater quantities of at least one good, assuming more consumption leads to greater utility (non-satiation principle). Consumers always prefer combinations on higher indifference curves.

4. Indifference Curves Do Not Intersect

One of the most critical properties is that indifference curves cannot intersect. If two curves were to intersect, it would imply that the same combination of goods offers two different levels of satisfaction, which is logically inconsistent. This principle is rooted in the transitivity of preferences: if a consumer prefers bundle A to B and B to C, they must also prefer A to C.

5. Indifference Curves are Non-Thick

Indifference curves are thin and continuous. A thick curve would imply that multiple points along it represent the same utility level, which contradicts the principle of precise preferences. Continuity ensures there are no sudden jumps or gaps in consumer preferences.

6. Shape Variations Depending on Preferences

While most indifference curves are convex, their shapes can vary based on consumer preferences:

- Perfect Substitutes: Indifference curves are straight lines with a constant slope, indicating a fixed trade-off ratio between two goods.

- Perfect Complements: Indifference curves take an L-shape, representing goods that are consumed in fixed proportions.

Can Indifference Curves Be Parallel?

Indifference curves are not necessarily parallel in most practical scenarios, and their spacing depends on the consumer’s marginal rate of substitution and preferences.

Non-Parallel Indifference Curves:

- The spacing between curves often varies due to the diminishing marginal utility of goods. For example, moving from one curve to a higher curve may require increasing consumption of one good at a changing rate, resulting in non-uniform spacing.

- The slope of indifference curves can change due to different substitution patterns, leading to variations in their relative positions.

Exceptions and Parallelism:

- In the special case of perfect substitutes, indifference curves are parallel because the trade-off rate (MRS) between two goods is constant. The consumer views the two goods as interchangeable at a fixed ratio, resulting in equidistant and uniformly spaced curves.

- However, for most real-world preferences, the curves are not parallel, as individual utility functions vary in complexity and shape.

Conclusion

The properties of indifference curves—such as their downward slope, convexity, and inability to intersect—are essential to understanding consumer choice theory. While indifference curves can be parallel in certain theoretical scenarios like perfect substitutes, they are typically not parallel due to the changing marginal rate of substitution and the inherent complexity of human preferences. These properties provide a robust framework for analyzing consumer behavior and the dynamics of choice in economic systems.

Revealed Preference Theory (RPT) is an economic concept that gauges consumer preferences based on the goods they purchase under various price and income scenarios. It was developed to reconcile the utility and demand theories by analyzing customers’ behavior through utility functions.

Revealed preference theory

The belief that customers act rationally roots the foundation of the theory. By holding the price of goods and customers’ income constant, one can determine their purchasing preferences. The theory is best understood through the Weak Axiom of Revealed Preference (WARP), Strong Axiom of Revealed Preference (SARP), and Generalized Axiom of Revealed Preference (GARP).

Revealed preference theory is an economic model to uncover individual preferences based on observed buying patterns.

Revealed preference theory provides a useful tool for analyzing and predicting consumer behavior, particularly regarding how consumers react to price changes and income levels.

It reconciles the utility concept with demand theory by assuming customer choices reflect their preferences. The theory assumes constant prices, incomes, and consistent consumer tastes over time.

Researchers have identified eight main limitations of the theory, including the fact that individual choices may not always reflect true preferences.

Revealed Preference Theory in Economics

Revealed preference theory’s axioms provide a systematic framework for analyzing and evaluating consumer choices, allowing businesses and policymakers to make informed decisions based on consumer behavior patterns. By understanding customers’ preferences, companies can better tailor their products and services to meet their needs, increasing sales and customer satisfaction. It, thus, is essential for understanding consumer preferences by examining their purchasing behavior.

In 1938, economist Paul Anthony Samuelson developed the theory of RPT to quantify the revealed preference theory of consumer behavior. Samuelson illustrated that if a person is given two commodities to choose from (A & B) and two combinations of these commodities (X & Y) with the same quality and price, the person will choose the combination (X) over (Y) because they prefer it.

The price line represents the customer’s real income-price situation, and the consumer may choose any combination on or to the left of the price line, creating a choice triangle from which they can buy any goods. Consumers consider combinations on the price line equally desirable, deem combinations below the price line inferior, and consider those above the price line superior. The difference between the preferred and inferior zones is known as the ignorance zone.

In summary, RPT provides an essential framework for analyzing consumer behavior and understanding their preferences by examining their purchasing decisions at different prices and income levels.

Assumptions

Assumptions of revealed preference theory:

- Consumer tastes remain constant over time.

- The choices a consumer makes reveal their preferences.

- On a price-income line, the consumer selects only one combination.

- Consumers prefer larger sets of goods to smaller ones.

- Consumers have complete and transitive preferences, meaning that if A is preferred over B, and B is preferred over C, then A is preferred over C.

- Consumer behavior exhibits consistency over time.

- Consumers demand more goods as their income increases and less as their income decreases.

- A consumer will purchase more of a product if the price drops significantly.

Diagram

Let us look into the diagrammatic representation of revealed preference theory:

The revealed preference theory is a way of understanding people’s preferences based on their observable behavior, such as buying decisions. People often depict the theory graphically using a simple budget constraint diagram.

The revealed preference theory is a way of understanding people’s preferences based on their observable behavior, such as buying decisions. People often depict the theory graphically using a simple budget constraint diagram.

The diagram consists of two axes: the horizontal axis represents the quantity of one good, and the vertical axis represents the quantity of another good. The budget constraint is a straight line that shows all the combinations of the two goods that can occur with a given income level and the prices of the goods. The slope of the budget constraint represents the relative prices of the two goods.

The area under the budget constraint represents all the available feasible consumption bundles, given the income level and prices of the goods. Any point on the budget constraint represents a particular consumption bundle that exhausts the consumer’s income. The area above the budget constraint represents unaffordable consumption bundles, given the income level and prices of the goods.

Overall, the revealed preference theory graph provides a visual representation of how consumers choose to allocate their limited income among different goods based on their preferences and the prices of the goods.

Limitations

Despite its merits, like being realistic, scientific, consistent, and based on minimal assumptions, the revealed preference theory has faced some criticism. The limitations of RPT theory are the following:

- It does not account for the possibility of indifferences in consumer behavior.

- It fails to distinguish between the income and substitution effect of a price change.

- It only derives the demand curve of an individual and not the market demand curve.

- It considers the consumer behavior of only individuals governed by existing market conditions.

- RPT does not consider that consumers can choose from multiple combinations instead of only one.

- The choice made by the consumer does not necessarily reflect their true preference.

- Game theory becomes invalid under RPT.

- RPT tends to fail in risky or ambiguous situations.

Microeconomics is the study of individuals and business decisions, whereas macroeconomics considers the decisions of nations and governments. Though these two branches of economics appear to be varied, they are interdependent and complement one another. Many overlapping issues exist between the two fields. Microeconomics and macroeconomics are two branches of economics that analyze different aspects of economic behavior and outcomes at different levels of aggregation. While microeconomics focuses on individual agents and markets, macroeconomics examines the economy as a whole. Understanding the principles and concepts of both branches is essential for comprehending the functioning of economies and informing policy decisions.

Microeconomics Meaning

Microeconomics is the branch of economics that focuses on the behavior of individual agents and specific markets within the economy. It examines how individual consumers, firms, and households make decisions regarding the allocation of resources and how their interactions in markets determine prices, quantities, and resource allocation. Key topics in microeconomics include supply and demand, consumer behavior, production and costs, market structures (such as perfect competition and monopoly), and the allocation of resources.

Nature of Microeconomics

The terms „microeconomics‟ and „macroeconomics‟ have been coined by a Norwegian economist Ragnar Frisch in 1933. The word micro is derived from a Greek word mikros which means small. When economic problems or economic issues are studied considering small economic units like an individual consumer or an individual producer, we are referring to microeconomics. The basic economic problem is the problem of choice related to allocation of scarce resources to alternative uses at an individual level ( both consumer & producer). As Gardner Ackley says, “Microeconomics deals with the division of total output among industries, products and firms and the allocation of resources among competing groups. It considers problems of income distribution. Its interest is in relative prices of particular goods and services.” According to Maurice Dobb, Microeconomics is, in fact, a microscopic study of the economy. It is like looking at the economy through a microscope to find out the working of markets for individual commodities and the behavior of individual consumers and producers.

Scope of Microeconomics

The scope or the subject matter of microeconomics is concerned with:

- Product Pricing: The price of an individual commodity is determined by the market forces of demand and supply. Demand for goods and services and consumer‟s choice on the allocation of his income to different uses are the issues studied in the theory of consumer behavior or theory of demand and the problems faced by a producer in deciding the product and combination of inputs used comes under the theory of producer behavior or theory of supply.

- Factor Pricing Theory: Microeconomics helps in determining the factor prices for land, labor, capital and entrepreneurship in the form of rent ,wages, interest and profit respectively. These are the factors which contribute to the production process.

- Theory of Economic Welfare: The welfare component in microeconomics is concerned with solving the problems in attaining economic efficiency to maximize public welfare. It attempts to gain efficiency in production, consumption/distribution to attain overall efficiency and provides answers for „What to produce?‟, „When to produce?‟, „How to produce?‟, and „For whom to produce?‟.

Importance of Microeconomics

- Individual Behaviour Analysis: Microeconomics helps in studying the behaviour of individual consumer or producer in different situations where individual has freedom to take his own economic decisions.

- Resource Allocation: We know that resources are limited in nature as compared to their demand and for that we have to use them judiciously. Microeconomics helps in proper allocation and utilization of these scarce resources to produce various types of goods and services.

- Tools for Economic Policies: Microeconomics through price or market mechanism helps the state in formulating correct price policies and their evaluation in proper perspective.

- Economic Policy: Microeconomics helps in the formulation of economic plans and policies to promote all round economic development.

- Understanding the Problems of Taxation: Microeconomics helps the government in fixing the tax rate and the type of tax as well as the amount of tax to be charged to the buyer and the seller.

- Helpful in International Trade: Microeconomics helps in explaining and fixing international trade and tariff rules, gains from trade, causes of disequilibrium in BOP and the determination of the foreign exchange rate.

- Social Welfare: Microeconomics not only analyse economic conditions but also studies the social needs under different market conditions like monopoly, oligopoly etc. It helps in suggesting ways and means of eliminating wastages in order to bring maximum welfare.

Macroeconomics Meaning

Macroeconomics, on the other hand, is the branch of economics that studies the economy as a whole. It focuses on aggregate measures and trends, such as national income, unemployment, inflation, and economic growth. Macroeconomics seeks to understand the determinants of broad economic outcomes and the relationships between key variables, such as consumption, investment, government spending, and exports. Key topics in macroeconomics include national income accounting, aggregate demand and supply, fiscal policy, monetary policy, and economic fluctuations (business cycles).

Difference between Microeconomics and Macroeconomics?

Aspect | Microeconomics | Macroeconomics |

Scope of Analysis | Focuses on individual agents (consumers, firms) and specific markets. | Focuses on the economy as a whole, including aggregate measures. |

Units of Analysis | Individuals, households, firms, and specific markets. | Aggregate measures such as national income, inflation, and unemployment. |

Questions Addressed | Examines how individual choices and behaviors impact market outcomes. | Analyzes overall economic trends, including growth, inflation, and unemployment. |

Key Concepts | Supply and demand, consumer behavior, producer theory, market structures. | National income accounting, aggregate demand and supply, economic fluctuations. |

Market Structures Studied | Perfect competition, monopoly, oligopoly, monopolistic competition. | Influence of government policies, international trade, and financial markets. |

Policy Implications | Insights into market efficiency, consumer welfare, and firm behavior. | Informs monetary and fiscal policies to stabilize the economy and promote growth. |

Examples of Topics | Pricing decisions, labor markets, consumer preferences. | Economic growth, inflation targeting, fiscal stimulus. |

Examples of Microeconomics and Macroeconomics

Microeconomics and macroeconomics are two branches of economics that study different aspects of the economy:

Microeconomics

- Supply and Demand: Microeconomics analyzes the interactions between buyers and sellers in specific markets, focusing on how prices are determined by supply and demand.

- Consumer Behavior: It examines how individuals make decisions about what to buy, how much to work, and how to allocate their resources.

- Firm Behavior: Microeconomics studies the behavior of individual firms, including production decisions, cost minimization, and pricing strategies.

- Market Structures: It investigates various market structures such as perfect competition, monopoly, monopolistic competition, and oligopoly, and their implications for efficiency and market outcomes.

- Factor Markets: Microeconomics explores markets for factors of production, such as labor and capital, and analyzes how factor prices are determined.

Macroeconomics

- Aggregate Output and Income: Macroeconomics examines the economy as a whole, focusing on variables such as GDP (Gross Domestic Product), national income, and overall production levels.

- Unemployment: It studies the causes and consequences of unemployment at the national level, including theories of unemployment and policies to reduce it.

- Inflation: Macroeconomics analyzes the causes and effects of inflation, as well as policies to control inflation.

- Economic Growth: It investigates the factors that determine long-term economic growth, including productivity, technological progress, and capital accumulation.

- Monetary and Fiscal Policy: Macroeconomics examines the role of government policies, such as monetary policy (controlled by central banks) and fiscal policy (controlled by governments), in stabilizing the economy and achieving macroeconomic objectives like full employment and price stability.

- International Trade and Finance: It studies the interactions between countries in terms of trade, exchange rates, balance of payments, and international capital flows.

Conclusion

Microeconomics and macroeconomics are essential branches of economics that provide insights into different levels of economic analysis. While microeconomics focuses on individual agents and markets, macroeconomics examines the economy as a whole. By studying the principles and concepts of both branches, economists can better understand the complex interactions and dynamics of modern economies and develop policies to address economic challenges and promote prosperity. A comprehensive understanding of microeconomics and macroeconomics is vital for informed decision-making in both private and public sectors, contributing to economic well-being and societal welfare.

As price of a good X falls, other things remaining the same, consumer would move to a new equilibrium position at a higher indifference curve and would buy more of good X at the lower price unless it is a Giffen good.

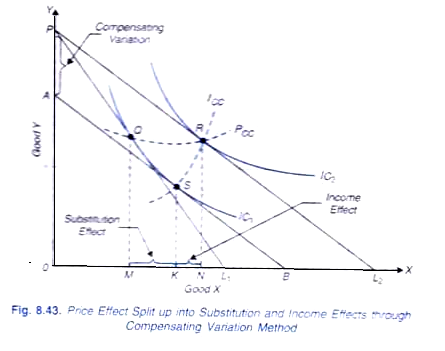

Thus, in the Fig. 8.43 the consumer who is initially in equilibrium at Q on indifference curve IC1 moves to the point R on indifference curve IC2 when the price of good X falls and the budget line twists from PL1 to PL2.

The movement from Q to R represents the price effect. It is now highly important to understand that this price effect is the net result of two distinct forces, namely substitution effect and income effect. In other words, price effect can be split up into two different parts, one being the substitution effect and the other income effect.

There are two approaches for decomposing price effect into its two parts, substitution effect and income effect. They are the Hicksian approach and Slutsky approach.

Further, Hicksian approach uses two methods of splitting the price effect, namely:

- Compensating variation in income

- Equivalent variation in income.

Slutsky uses cost-difference method to decompose price effect into its two component parts. How the price effect can be decomposed into income effect and substitution effect by the Hicksian methods is explained below.

Breaking up Price Effect: Compensating Variation in Income

In the method of breaking up price effect by compensating variation we adjust the income of the consumer so as to offset the change in satisfaction resulting from the change in price o a good and bring the consumer back to his original indifference curve, that is, his initial level of satisfaction which he was obtaining before the change in price occurred. For instance, when the price of a commodity falls and consumer moves to a new equilibrium position at a higher indifference curve his satisfaction increases.

To offset this gain in satisfaction resulting from a fall in price of the good we must take away from the consumer enough income to force him to come back to his original indifference curve. This required reduction in income (say, through levying a lump sum tax) to cancel out the gain in satisfaction or welfare occurred by reduction in price of a good is called compensating variation in income.

This is so called because It compensates (in a negative way) for the gain in satisfaction resulting from a price reduction of the commodity. How the price effect is broken up into substitution effect and income effect through the method of compensating variation in income is illustrated in Fig 8.43.

When price of good X falls and as a result budget line shifts to PL2, the real income of the consumer rises, i.e., he can buy more of both the goods with his given money income. That is, price reduction enlarges consumer’s opportunity set of the two goods. With the new budget line PL2 he is in equilibrium at point R on a higher indifference curve IC2 and thus gains in satisfaction as a result of fall in price of good X.

When price of good X falls and as a result budget line shifts to PL2, the real income of the consumer rises, i.e., he can buy more of both the goods with his given money income. That is, price reduction enlarges consumer’s opportunity set of the two goods. With the new budget line PL2 he is in equilibrium at point R on a higher indifference curve IC2 and thus gains in satisfaction as a result of fall in price of good X.

Now, if his money income is reduced by the compensating variation in income so that he is forced to come back to the original indifference curve IC1 he would buy more of X since X has now become relatively cheaper than before. In Fig. 8.43 as result of the fall in price of X, price line switches to PL2. Now, with the reduction in income by compensating variation, budget line shifts to AB which has been drawn parallel to PL2 so that it just touches the indifference curve IC1 where he was before the fall in price of X.

Since the price line AB has got the same slope as Pig, it represents the changed relative prices with X being relatively cheaper than before. Now, X being relatively cheaper than before, the consumer in order to maximise his satisfaction in the new price income situation substitutes X for Y.

Thus, when the consumer’s money income is reduced by the compensating variation in income (which is equal to PA in terms of Y or L2B in terms of X), the consumer moves along the same indifference curve IC1 and substitutes X for Y. With price line AB, he is in equilibrium at S on indifference curve IC1 and is buying MK more of X in place of Y. This movement from Q to S on the same indifference curve IC1 represents the substitution effect since it occurs due to the change in relative prices alone, real income remaining constant.

If the amount of money income which was taken away from him is now given back to him, he would move from S on indifference curve IC1 to R on a higher indifference curve IC2. The movement from Son a lower in difference curve to R on a higher in difference curve is the result of income effect. Thus the movement from Q to R due to price effect can be regarded as having been taken place into two steps first from Q to S as a result of substitution effect and second from S to R as a result of income effect. In is thus manifest that price effect is the combined result of a substitution effect and an income effect.

In Fig. 8.43 the various effects on the purchases of good X are:

Price effect = MN

Substitution effect = MK

Income effect = K/V

MN = MK+KN or

Price effect = Substitution effect + Income effect

From the above analysis, it is thus clear that price effect is the sum of income and substitution effects.

Breaking up Price Effect: Equivalent Variation in Income

As mentioned above, price effect can be split up into substitution and income effects” through an alternative method of equivalent variation in income. The reduction in price of a commodity increases consumer’s satisfaction as it enables him to reach a higher indifference curve. Now, the same increase in satisfaction can be achieved through bringing about an increase in his income, prices remaining constant.

The increase in income of the consumer prices of goods remaining the same, so as to enable him to move to a higher subsequent indifference curve at which he in fact reaches with reduction in price of a good is called equivalent variation in income because it represents the variation in income that is equivalent in terms of gain in satisfaction to a reduction in price of the good.

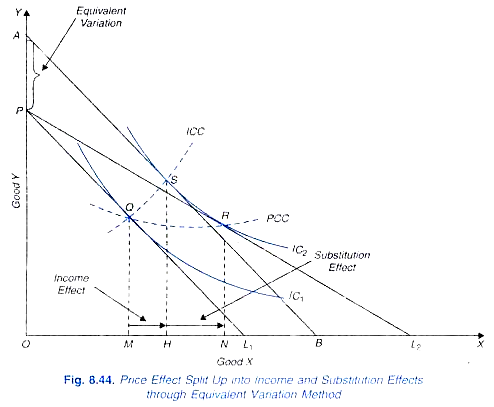

Thus, in this equivalent income-variation method substitution effect is shown along the subsequent indifference curve rather than the original one. How this price effect is decomposed into income and substitution effects through equivalent variation in income is shown in Fig. 8.44.

When price of good X falls, the consumer can purchase more of both the goods, that is, the purchasing power of his given money income rises. It means that after the fall in price of X if the consumer buys the same quantities of goods as before, then some amount of money will be left over. In other words, the fall in price of good X will release some amount of money. Money thus released can be spent on purchasing more of both the goods.

It therefore follows that a change in price of the good produces an income effect. When the power to purchase goods rises due to the income effect of the price change, the consumer has to decide how this increase in his purchasing power is to be spread over the two goods he is buying. How he will spread the released purchasing power over the two goods depends upon the nature of his income consumption curve which in turn is determined by his preferences about the two goods.

From above it follows, that, as a result of the increase in his purchasing power (or real income) due to the fall in price, the consumer will move to a higher indifference curve and will become better off than before. It is as if price had remained the same but his money income was increased. In other words, a fall in price of good X does to the consumer what an equivalent rise in money income would have done to him.

As a result of fall in price of X, the consumer can therefore be imagined as moving up to a higher indifference curve along the income consumption curve as if his money income had been increased, prices of X and Y remaining unchanged. Thus, a given change in price can be thought of as an equivalent to an appropriate change in income.

It will be seen from Fig. 8.44 that with price line PL1, the consumer is in equilibrium at Q on indifference curve IC1. Suppose price of good X falls, price of Y and his money income remaining unaltered, so that budget line is now PL2. With budget line PL2, he is in equilibrium at R on indifference curve IC2. Now, a line AB is drawn parallel to PL1 so that it touches the indifference curve IC2 at S.

It means that the increase in real income or purchasing power of the consumer as a result of the fall in price of X is equal to PA in terms of Y or L1B in terms of X Movement of the consumer from Q on indifference curve IC1 to S on the higher indifference curve IC2 along the income consumption curve is the result of income effect of the price change. But the consumer will not be finally in equilibrium at S.

This is because now that X is relatively cheaper than Y, he will substitute X, which has become relatively cheaper, for good Y, which has become relatively dearer. It will be gainful for the consumer to do so. Thus the consumer will move along the indifference curve IC2 from S to R. This movement from S to R has taken place because of the change in relative prices alone and therefore represents substitution effect. Thus the price effect can be broken up into income and substitution effects, showing in this case substitution along the subsequent indifference curve.

In Fig 8.44 the magnitudes of the various effects are:

Price effect = MN

Income effect = MH

Substitution effect = HN

In Fig. 8.44 effect = MMH + HN

Price effect = Income Effect + Substitution Effect

Introduction

According to ‘Law of Demand’, quantity demanded increases with fall in price and decreases with rise in price. The law of demand gives us the direction of change in the quantity demanded as a result of a change in price, but it does not specify the magnitude, amount or the extent by which the quantity demanded changes with a change in its price. In brief, it does not indicate, how much change’ in the quantity demanded due to change in price. Therefore, the concept of ‘Elasticity of Demand’ was developed to measure the magnitude of change in the quantity demanded.

For More Clarity

Suppose, price of computer falls by 20%.

- According to Law of demand, the quantity of computers demanded will increase due to fall in its price. However, it does not indicate, by how much quantity demanded of computers will increase.

- In such cases, the concept of Elasticity of Demand becomes important as it helps in knowing “how much”.

The concept of elasticity was developed by Prof. Marshall in his book ‘Principles of Economics’. Now-a-days, this concept has great importance in economic theory as well as in applied economics.

Concept Of Elasticity Of Demand

Demand for a commodity is affected by a number of factors like change in its own price, change in the income of consumer, change in the prices of related goods, etc. Elasticity of demand refers to the percentage change in demand for a commodity with respect to percentage change in any of the factors affecting demand for that commodity. Elasticity of demand can be calculated as:

Elasticity of Demand = \(\frac{Percentage\;Change\;in\;Demand\;for\;X}{Percentage\;Change\;in\;a\;factor\;affecting\;the\;Demand\;for\;X}\)

Out of various determinants of demand, there are 3 quantifiable determinants of demand: (1) Price of the given commodity; (2) Price of related goods; (3) Income of the consumer. So, we have 3 dimensions of elasticity of demand:

- Price elasticity of demand: Price elasticity of demand refers to the percentage change in demand for a commodity with respect to percentage change in the price of the given commodity.

- Cross elasticity of demand: Cross elasticity of demand refers to the percentage change in demand for a commodity with respect to percentage change in the price of a related good (substitute good or complementary good).

- Income elasticity of demand: Income elasticity of demand refers to the percentage change in demand for a commodity with respect to percentage change in the income of consumer.

Cross and Income Elasticity of Demand are beyond the scope of Class XII syllabus. So, present chapter deals with ‘Price Elasticity of Demand”.

Price Elasticity Of Demand

Price Elasticity of Demand means the degree of responsiveness of demand for a commodity with reference to change in the price of such commodity.

Some Noteworthy Points about Price Elasticity of Demand

- It establishes a quantitative relationship between quantity demanded of a commodity and its price, while other factors remain constant.

- Higher the numerical value of elasticity, larger is the effect of a price change on the quantity demanded.

- For certain goods, a change in price leads to a greater change in the demand, whereas, in some cases, there is a small change in demand due to change in price. For example, if prices of two commodities ‘x’ and ‘y’ rise by 10% and their demands fall by 20% and 5% respectively, then commodity ‘x’ is said to be more elastic as compared to commodity ‘y’.

- Price is the most important determinant of demand. So, price elasticity of demand is sometimes shortened as ‘Elasticity of Demand’ or ‘Demand Elasticity’ or simply ‘Elasticity’ Unless otherwise stated, whenever these words are used, they mean ‘Price Elasticity of Demand’.

Degrees Of Elasticities Of Demand

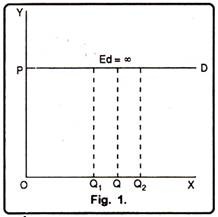

1. Perfectly Elastic Demand

Perfectly elastic demand is said to happen when a little change in price leads to an infinite change in quantity demanded. A small rise in price on the part of the seller reduces the demand to zero. In such a case the shape of the demand curve will be horizontal straight line as shown in figure 1.

The figure 1 shows that at the ruling price OP, the demand is infinite. A slight rise in price will contract the demand to zero. A slight fall in price will attract more consumers but the elasticity of demand will remain infinite (ed=∞). But in real world, the cases of perfectly elastic demand are exceedingly rare and are not of any practical interest.

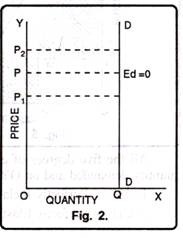

2. Perfectly Inelastic Demand

Perfectly inelastic demand is opposite to perfectly elastic demand. Under the perfectly inelastic demand, irrespective of any rise or fall in price of a commodity, the quantity demanded remains the same. The elasticity of demand in this case will be equal to zero (ed = 0).

In diagram 2 DD shows the perfectly inelastic demand. At price OP, the quantity demanded is OQ. Now, the price falls to OP1, from OP, the demand remains the same. Similarly, if the price rises to OP2 the demand still remains the same. But just as we do not see the example of perfectly elastic demand in the real world, in the same fashion, it is difficult to come across the cases of perfectly inelastic demand because even the demand for, bare essentials of life does show some degree of responsiveness to change in price.

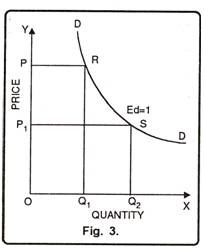

3. Unitary Elastic Demand

The demand is said to be unitary elastic when a given proportionate change in the price level brings about an equal proportionate change in quantity demanded. The numerical value of unitary elastic demand is exactly one i.e. Marshall calls it unit elastic.

In figure 3, DD demand curve represents unitary elastic demand. This demand curve is called rectangular hyperbola. When price is OP, the quantity demanded is OQ\. Now price falls to OP1 the quantity demanded increases to OQ2. The area OQ\RP = area OP\SQ2 in the fig. denotes that in all cases price elasticity of demand is equal to one.

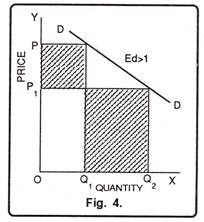

4. Relatively Elastic Demand

Relatively elastic demand refers to a situation in which a small change in price leads to a big change in quantity demanded. In such a case elasticity of demand is said to be more than one (ed > 1). This has been shown in figure 4.

In fig. 4, DD is the demand curve which indicates that when price is OP the quantity demanded is OQ1. Now the price falls from OP to OP1, the quantity demanded increases from OQ1 to OQ2 i.e. quantity demanded changes more than change in price.’

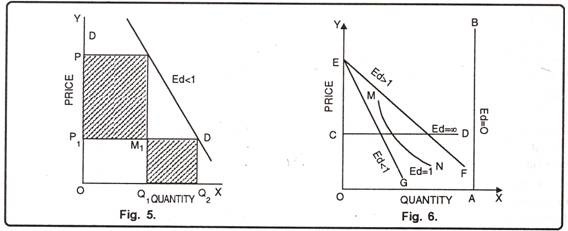

5. Relatively Inelastic Demand

Under the relatively inelastic demand, a given percentage change in price produces a relatively less percentage change in quantity demanded. In such a case elasticity of demand is said to be less than one (ed < 1). It has been shown in figure 5.

All the five degrees of elasticity of demand have been shown in figure 6. On OX axis, quantity demanded and on OY axis price is given.

It shows:

1. AB — Perfectly Inelastic Demand

2. CD — Perfectly Elastic Demand

3. EG — Less than Unitary Elastic Demand

4. EF — Greater Than Unitary Elastic Demand

5. MN — Unitary Elastic Demand.

Factors Affecting Price Elasticity of Demand

A change in price does not always lead to the same proportionate change in demand. For example, a small change in price of AC may affect its demand to a considerable extent, whereas, large change in price of salt may not affect its demand. So, elasticity of demand is different for different goods.

Various factors which affect the elasticity of demand of a commodity are:

- Nature of commodity: Elasticity of demand of a commodity is influenced by its nature. A commodity for a person may be a necessity, a comfort or a luxury. When a commodity is a necessity like food grains, vegetables, medicines, etc., its demand is generally inelastic as it is required for human survival and its demand does not fluctuate much with change in price. When a commodity is a comfort like fan, refrigerator, etc., its demand is generally elastic as consumer can postpone its consumption. When a commodity is a luxury like AC, DVD player, etc., its demand is generally more elastic as compared to demand for comforts. The term ‘luxury’ is a relative term as any item (like AC), may be a luxury for a poor person but a necessity for a rich person.

- Availability of substitutes: Demand for a commodity with large number of substitutes will be more elastic. The reason is that even a small rise in its prices will induce the buyers to go for its substitutes. For example, a rise in the price of Pepsi encourages buyers to buy Coke and vice-versa. Thus, availability of close substitutes makes the demand sensitive to change in the prices. On the other hand, commodities with few or no substitutes like wheat and salt have less price elasticity of demand.

- Income Level: Elasticity of demand for any commodity is generally less for higher income level groups in comparison to people with low incomes. It happens because rich people are not influenced much by changes in the price of goods. But, poor people are highly affected by increase or decrease in the price of goods. As a result, demand for lower income group is highly elastic.

- Level of price: Level of price also affects the price elasticity of demand. Costly goods like laptop, AC, etc. have highly elastic demand as their demand is very sensitive to changes in their prices. However, demand for inexpensive goods like needle, match box, etc. is inelastic as change in prices of such goods do not change their demand by a considerable amount.

- Postponement of Consumption: Commodities like biscuits, soft drinks, etc. whose demand is not urgent, have highly elastic demand as their consumption can be postponed in case of an increase in their prices. However, commodities with urgent demand like life saving drugs, have inelastic demand because of their immediate requirement.

- Number of Uses: If the commodity under consideration has several uses, then its demand will be elastic. When price of such a commodity increases, then it is generally put to only more urgent uses and, as a result, its demand falls. When the prices fall, then it is used for satisfying even less urgent needs and demand rises. For example, electricity is a multiple-use commodity. Fall in its price will result in substantial increase in its demand, particularly in those uses (like AC, Heat convector, etc.), where it was not employed formerly due to its high price. On the other hand, a commodity with no or few alternative uses has less elastic demand. 7. Share in Total Expenditure: Proportion of consumer’s income that is spent on a particular commodity also influences the elasticity of demand for it. Greater the proportion of income spent on the commodity, more is the elasticity of demand for it and vice-versa. Demand for goods like salt, needle, soap, match box, etc. tends to be inelastic as consumers spend a small proportion of their income on such goods. When prices of such goods change, consumers continue to purchase almost the same quantity of these goods. However, if the proportion of income spent on a commodity is large, then demand for such a commodity will be elastic.

- Time Period: Price elasticity of demand is always related to a period of time. It can be a day, a week, a month, a year or a period of several years. Elasticity of demand buries directly with the time period. Demand is generally inelastic in the short period. It happens because consumers find it difficult to change their habits, in the short period, in order to respond to a change in the price of the given commodity. However, demand is more elastic in long run as it is comparatively easier to shift to other substitutes, if the price of the given commodity rises.

- Habits: Commodities, which have become habitual necessities for the consumers, have less elastic demand. It happens because such a commodity becomes a necessity for the consumer and he continues to purchase it even if its price rises. Alcohol, tobacco, cigarettes, etc. are some examples of habit forming commodities.

Finally it can be concluded that elasticity of demand for a commodity is affected by number of factors. However, it is difficult to say, which particular factor or combination of factors determines the elasticity. It all depends upon circumstances of each case.

In economics, demand is the quantity of a good or service that a consumer is willing and able to purchase at different price levels available during a given time period. Although demand is the desire of a consumer to purchase a commodity, it is not the same as desire. Desire is just a wish of a consumer to purchase a commodity even though he is unable to buy it. However, demand is a consumer’s desire to purchase a commodity, provided he is willing to spend and has sufficient purchasing power. Hence, we can say that the four essential elements of demand are Quantity of the commodity, Willingness of a consumer to purchase the commodity, Time period, and Price of the commodity at each quantity level.

Types of Demand

The nine different types of demand are as follows:

1. Price Demand

Assuming other factors as constant, a relationship between the price and demand of a commodity is known as Price Demand. Price Demand can be shown as:

Dx = f(Px)

Where,

Dx = Demand for the given Commodity

f = Functional Relationship

Px = Price of the given Commodity

2. Cross Demand

Assuming other things remaining as constant, a relationship between the demand of a given commodity and the price of related commodities is known as Cross Demand.

3. Income Demand

Assuming other factors as constant, a relationship between the consumer’s income and the quantity demanded for a commodity is known as Income Demand. Income Demand can be shown as:

Dx = f(Y)

Where,

Dx = Demand for the given Commodity

f = Functional Relationship

Y = Income of the Consumer

4. Joint Demand

When demand for two or more goods arises simultaneously for satisfying a particular want of the consumer, then such type of demand is known as Joint Demand. For example, the demand for milk, coffee beans, and sugar is a joint demand as all these goods are demanded together to prepare coffee.

5. Composite Demand

When a commodity can be used for more than one purpose, then such type of demand is known as Composite Demand. For example, the demand for water is a composite demand as it can be used for various purposes like bathing, drinking, cooking, etc.

6. Derived Demand

The kind of demand for a commodity, which depends on the demand for other goods, is known as Derived Demand. For example, demand for workers/labour, producing bags is a derived demand as it depends on the demand for bags.

7. Direct Demand

When a commodity directly satisfies the demand of consumers, then its demand is known as Direct Demand. For example, demand for books, stationery, clothes, food, etc., is a direct demand as these goods directly satisfy the wants.

8. Competitive Demand

When two commodities are close substitutes of each other and an increase in the demand for one commodity will decrease the demand for the other commodity, then the demand for any one of the commodities is known as Competitive Demand. For example, an increase in demand for tea might decrease the demand for coffee, which makes the demand for these goods competitive demand. This happens because when consumers purchase more of one commodity (say tea), it leads to a lesser requirement for the other commodity (say coffee).

9. Alternative Demand

Demand for a commodity is known as alternative demand when it can be satisfied by using different alternatives. For example, there are number of alternatives to satisfy the demand for clothes like jeans, shirts, trousers, suits, saree, pants, etc.

Law of Demand

Law of Demand states that there is an inverse relationship between the price and quantity demanded of a commodity, keeping other factors constant or ceteris paribus. It is also known as the First Law of Purchase.

There are several other factors besides the price of the given commodity that affect the quantity demanded of a commodity. Therefore, in order to understand the separate influence of one factor affecting the demand, it is essential that the other factors are kept constant. Hence, under the Law of Demand, it is assumed that other factors are constant.

Points to Remember

- The Law of Demand states that, everything else being constant, the quantity demanded of a good or service decreases as its price increases, and vice versa.

- The demand curve typically slopes downward from left to right, illustrating the negative correlation between price and quantity demanded.

- The Law of Demand applies both at the individual consumer level and across the entire market.

- The Law of Demand is often linked to the concept of diminishing marginal utility, which suggests that as consumers consume more units of a good, the additional satisfaction derived from each additional unit decreases.

Assumptions of Law of Demand

The assumptions on which the Law of Demand is based are as follows:

- The price of substitute goods does not change.

- The price of complementary goods also remains constant.

- The income of the consumer does not change.

- Tastes and preferences of the consumers remain the same.

- People do not expect the future price of the commodity to change.

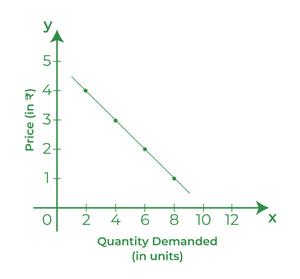

Graphical Presentation of Law of Demand

Let’s take an example to understand the concept of the Law of Demand better.

Price (in ₹) | Quantity Demanded |

|---|---|

4 | 2 |

3 | 4 |

2 | 6 |

1 | 8 |

The above table clearly shows that as the price of the commodity decreases, its quantity demanded increases. Also, the demand curve DD is sloping downwards from left to right, which means that there is an inverse relationship between the price and quantity demanded of the commodity.

Facts about Law of Demand

1. One-Side

As the Law of Demand only talks about the effect of change in price on the change in quantity demanded of a commodity and not about the effect of change in quantity demanded of a commodity on the change in its price, it is one-sided.