Ancient History – 3rd Year

Paper – III (Short Notes)

Unit I

Language/भाषा

The beginnings of Indian art are deeply rooted in the subcontinent’s ancient history, reflecting a unique confluence of indigenous traditions, religious beliefs, and external influences. Stretching across millennia, Indian art evolved as an integral part of the country’s cultural and spiritual expression. It encompasses diverse forms, from prehistoric rock art to sophisticated temple architecture, monumental sculpture, intricate paintings, and vibrant folk traditions.

The Prehistoric Foundations of Indian Art

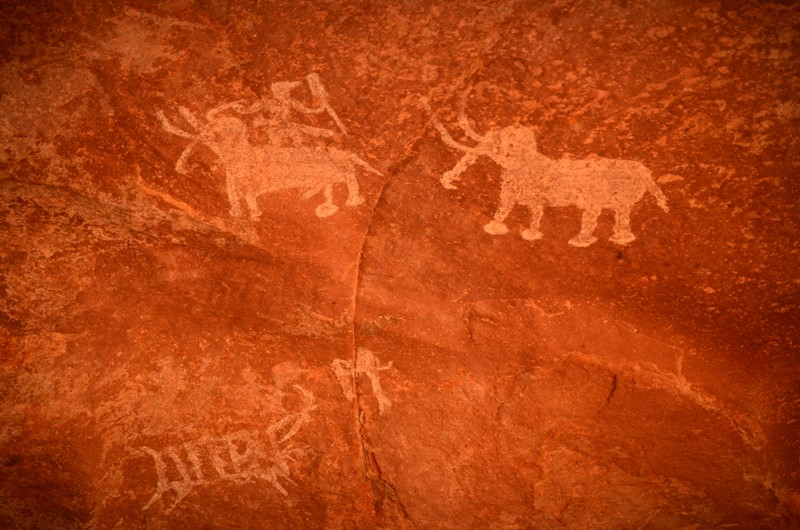

The earliest evidence of artistic expression in India dates back to the prehistoric period, with the discovery of rock art in caves and shelters across the subcontinent. The Bhimbetka Rock Shelters, located in present-day Madhya Pradesh, are among the most significant sites of prehistoric art in India. Declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site, these shelters contain pictographs and petroglyphs dating back to the Mesolithic period (around 10,000 BCE).

These early artworks predominantly feature depictions of hunting scenes, animals, human figures, and abstract symbols. Created using natural pigments like ochre and hematite, the paintings provide valuable insights into the lives of prehistoric communities. They showcase a deep connection with nature and reflect the early human desire to represent their environment and experiences visually. The stylistic simplicity of these depictions marked the foundation of India’s artistic journey, emphasizing narrative and symbolism, traits that continued to shape Indian art in later periods.

The Harappan Civilization and Early Urban Art

The Indus Valley Civilization (circa 2500–1900 BCE) marked a significant leap in the development of Indian art. As one of the world’s earliest urban civilizations, the Harappans left behind an impressive array of artistic artifacts that testify to their advanced aesthetic sensibilities. The art of the Harappan Civilization is characterized by its focus on functionality, symmetry, and intricate craftsmanship.

Terracotta figurines, seals, pottery, and ornamental jewelry are among the most remarkable examples of Harappan art. The seals, often made of steatite, bear engraved animal motifs, such as bulls, elephants, and unicorns, alongside undeciphered script. These seals, likely used for trade or religious purposes, reveal a sophisticated sense of design and symbolism. The famous “Dancing Girl” sculpture, a small bronze statuette discovered in Mohenjo-daro, exemplifies the Harappans’ mastery of bronze casting and their ability to capture movement and grace in their artworks.

While the exact meanings of Harappan artistic motifs remain elusive, they reflect the civilization’s emphasis on ritualistic and utilitarian aesthetics. The Harappans laid the groundwork for many artistic traditions that would reemerge in later Indian civilizations, particularly in their focus on ornamentation and narrative imagery.

Vedic Period: Symbolism and Ritual Art

The Vedic period (circa 1500–500 BCE) marked a transitional phase in Indian art, where the focus shifted from urban sophistication to rural and pastoral simplicity. While this period is primarily known for its oral literary tradition—the composition of the Vedas—its artistic expressions were closely tied to ritual practices and symbolic representations.

Vedic art is evident in the creation of ritual altars, yajnas (sacrificial pits), and sacred geometries used in religious ceremonies. The emphasis on fire worship, celestial deities, and the cosmic order influenced the aesthetic sensibilities of this period. Though less tangible compared to the urban art of the Harappans, the Vedic era laid the foundation for iconographic and architectural traditions that would later flourish in Indian art.

The Mauryan Era: The Rise of Monumental Art

The Mauryan Empire (circa 321–185 BCE) marked a transformative phase in Indian art, characterized by the first large-scale use of stone for monumental sculptures and architecture. The Mauryan period reflects the influence of both indigenous traditions and Persian and Hellenistic styles, as the empire maintained extensive trade and diplomatic ties with the West.

One of the most iconic contributions of the Mauryan period is the Ashokan Pillars, erected by Emperor Ashoka as part of his efforts to spread the teachings of Buddhism. These monolithic pillars, carved out of polished sandstone, are inscribed with edicts promoting ethical conduct, religious tolerance, and non-violence. The Lion Capital of Sarnath, which crowns one such pillar, exemplifies the Mauryan artisans’ skill in carving intricate details. This sculpture, now the national emblem of India, symbolizes strength, courage, and dharma.

In addition to the pillars, the Mauryan period saw the construction of stupas, domed structures that served as reliquaries for Buddhist relics. The Great Stupa at Sanchi, originally built during Ashoka’s reign, represents the early development of Buddhist architectural art. Its simple yet symbolic design laid the groundwork for more elaborate stupas in later periods.

Post-Mauryan Period: The Flourishing of Religious Art

Following the decline of the Mauryan Empire, Indian art witnessed a period of regional diversification and religious flourishing. The Shunga, Satavahana, and Kushan dynasties played pivotal roles in shaping Indian artistic traditions during this period. The influence of Buddhism, Jainism, and Hinduism became increasingly evident in artistic expressions, as these religions sought to communicate their doctrines through visual and architectural forms.

The Gandhara and Mathura schools of art, emerging during the Kushan period, are particularly noteworthy. The Gandhara school, heavily influenced by Greco-Roman aesthetics, is characterized by its realistic representations of the Buddha and narrative reliefs depicting his life. The Mathura school, in contrast, developed a distinct indigenous style, emphasizing idealized forms and spiritual expression. Together, these schools laid the foundation for the development of Buddhist iconography, including the creation of the Buddha image, which became central to Buddhist art across Asia.

This period also saw the expansion of rock-cut architecture, with the creation of cave monasteries such as those at Ajanta, Ellora, and Barabar Hills. These caves, adorned with intricate carvings and paintings, served as centers of meditation and worship, reflecting the symbiotic relationship between art and religion in Indian culture.

Gupta Period: The Classical Age of Indian Art

The Gupta Empire (circa 320–550 CE) is often regarded as the Golden Age of Indian art, marked by a synthesis of earlier traditions and the emergence of new aesthetic ideals. Gupta art is characterized by its emphasis on grace, harmony, and spiritual symbolism. This period witnessed the refinement of Buddhist, Hindu, and Jain art, with a focus on creating visually appealing and spiritually uplifting works.

The Gupta period is renowned for its sculptural masterpieces, such as the Buddha images from Sarnath, which embody serenity and spiritual transcendence. The temple architecture of this era also reached new heights, as seen in the construction of Hindu temples like the Dashavatara Temple at Deogarh. These temples, with their intricate carvings and narrative panels, established the nagara style of temple architecture, which became a hallmark of northern India.

The Gupta period also contributed significantly to the development of painting, as exemplified by the murals of the Ajanta Caves. These vibrant frescoes, depicting scenes from the Jataka tales and other Buddhist narratives, showcase the Gupta artists’ mastery of composition, color, and emotional expression.

Conclusion

The beginnings of Indian art represent a rich tapestry of creativity, innovation, and cultural exchange. From the prehistoric rock art of Bhimbetka to the monumental sculptures and architecture of the Mauryan and Gupta periods, Indian art evolved as a reflection of the subcontinent’s diverse traditions and spiritual aspirations. Rooted in indigenous practices and enriched by external influences, early Indian art laid the foundation for the remarkable artistic legacy that continues to inspire and captivate the world. It is a testament to the enduring power of visual expression in shaping and preserving human history.

The ancient art of India is a profound testament to the subcontinent’s rich history, spiritual ethos, and cultural diversity. It serves as a window into the values, beliefs, and societal structures of its time. Spanning several millennia, Indian art has evolved through various phases, encompassing a wide array of forms such as architecture, sculpture, painting, and crafts. Each phase bears the imprint of distinct cultural, political, and religious influences, reflecting the dynamism of Indian civilization.

Integration of Religion and Art

A defining feature of ancient Indian art is its profound religious orientation. Much of it was created as a medium for spiritual expression and to communicate divine concepts to the masses. The earliest examples can be traced back to the Indus Valley Civilization (circa 2500–1500 BCE), where seals and figurines hint at proto-religious themes. The dancing girl of Mohenjo-daro and the priest-king statue demonstrate a fusion of artistic skill with potential spiritual symbolism.

As organized religions like Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism emerged, their influence on art became pronounced. Buddhist stupas, such as those at Sanchi and Amaravati, were constructed as architectural representations of the cosmic order. The stupas’ intricate carvings depict the Buddha’s life, the Jataka tales, and symbols like the lotus and wheel, which convey profound philosophical meanings. Similarly, Hindu temples such as those at Khajuraho and Konark were adorned with sculptures representing deities, mythological narratives, and cosmic functions, often blending spiritual messages with aesthetic appeal.

However, ancient Indian art was not solely confined to religious themes. Secular art also thrived, capturing aspects of daily life, nature, and royal grandeur, albeit often with an undercurrent of spiritual philosophy.

Symbolism and Allegory

Symbolism is a hallmark of ancient Indian art, where physical forms often serve as metaphors for abstract ideas. The lotus symbolizes purity and spiritual enlightenment, while the chakra (wheel) represents the cycle of life and dharma. The Nataraja form of Shiva, depicting the cosmic dance of creation and destruction, encapsulates profound philosophical concepts through dynamic visual representation. The recurring use of animals like lions, elephants, and peacocks reflects their symbolic significance in both religious and royal contexts.

Narrative Tradition

Ancient Indian art is deeply narrative in nature, serving as a medium to tell stories and convey moral or spiritual lessons. The rock-cut caves of Ajanta are a striking example, with their frescoes illustrating episodes from the Buddha’s life and the Jataka tales. These narratives are rendered with meticulous detail and emotional depth, drawing the viewer into the story. Similarly, the sculptural panels of temples and stupas often depict mythological episodes, emphasizing moral and spiritual ideals.

Human-Centric and Emotional Expression

One of the remarkable aspects of ancient Indian art is its human-centric approach, which emphasizes human emotions, forms, and experiences, even in religious contexts. Sculptures like the serene Buddha statues of Sarnath and the dynamic apsaras (celestial dancers) of Khajuraho capture the full range of human expression. The art emphasizes physical grace and spiritual tranquility, often merging the two seamlessly. The emotional depth seen in figures—whether divine, royal, or common—is a testament to the sophisticated understanding of human psychology.

Integration of Nature

Nature plays a significant role in ancient Indian art, often depicted not just as a backdrop but as a living, integral part of the cosmos. Flora and fauna are common motifs, symbolizing fertility, abundance, and the interconnectedness of life. The Yaksha and Yakshi sculptures, representing nature spirits, embody this harmony with the natural world. Architectural elements, like temple gardens and water bodies, further reflect this integration.

Diversity in Styles and Techniques

The vast geographical expanse and cultural diversity of India are reflected in the varied styles and techniques of ancient art. For example, the Gandhara School of Art, influenced by Hellenistic and Persian traditions, is characterized by realistic depictions of the human form and intricate drapery in its Buddhist sculptures. In contrast, the Mathura School is more indigenous in style, marked by robust, sensuous figures and a focus on symbolic expression. The Dravidian and Nagara styles of temple architecture, each with its distinct characteristics, illustrate regional variations in design and construction.

Architectural Innovation

Ancient Indian architecture stands out for its innovation and grandeur. The rock-cut caves of Ajanta, Ellora, and Elephanta showcase incredible skill in carving intricate structures directly into cliffs. The stupas, chaityas (prayer halls), and viharas (monastic residences) of Buddhism were not only places of worship but also architectural marvels. Hindu temples, like the Brihadeeswarar Temple in Tamil Nadu, exhibit sophisticated engineering and design principles, from towering vimanas to intricately carved mandapas (pillared halls). The use of materials like sandstone, granite, and laterite highlights the technical mastery of ancient Indian craftsmen.

Aesthetic and Functional Unity

Ancient Indian art exhibits a seamless integration of aesthetics and functionality. Whether it was the planning of urban spaces in the Indus Valley Civilization, the construction of water reservoirs, or the design of temples, beauty and utility were intertwined. The sculptures and carvings on temples often served both decorative and educational purposes, conveying moral and spiritual lessons to devotees.

Legacy and Cultural Continuity

A salient feature of ancient Indian art is its enduring legacy. The artistic traditions established during ancient times continue to influence modern Indian art and culture. The continuity of motifs, styles, and techniques underscores the resilience and adaptability of Indian art. Festivals, rituals, and contemporary crafts often draw upon ancient artistic themes, keeping this rich heritage alive.

Conclusion

Ancient Indian art is a magnificent tapestry of religious devotion, cultural diversity, and human creativity. Its salient features—ranging from its spiritual depth and narrative richness to its aesthetic sophistication and symbolic complexity—underscore the ingenuity and philosophical depth of the civilizations that produced it. While deeply rooted in spirituality, ancient Indian art also reflects the humanistic and secular dimensions of life, embodying a holistic vision of existence. Its legacy continues to inspire and inform, reminding us of the enduring power of art as a medium of expression, communication, and transcendence.

Pre-historic paintings offer a captivating glimpse into the artistic expressions of our ancient ancestors, shedding light on the early human cultures that existed long before written history. These artworks, dating back tens of thousands of years, were typically created on cave walls, rock surfaces, and other natural canvases using rudimentary tools and pigments derived from local materials like minerals, charcoal, and plant extracts. The subject matter of prehistoric paintings often revolved around hunting scenes, animals, and stylized human figures. Some of the most renowned examples include the magnificent cave paintings found in locations like Lascaux in France and Altamira in Spain, which reveal a remarkable level of skill and creativity even with limited resources.

The significance of prehistoric paintings lies not only in their aesthetic appeal but also in their role as a form of communication and storytelling. These ancient artworks are thought to have served various purposes, from recording important events and rituals to expressing spiritual beliefs and ensuring the survival of knowledge across generations. They provide valuable insights into the daily life, beliefs, and artistic capabilities of early humans and have deepened our understanding of our cultural heritage. The preservation of prehistoric paintings offers a bridge to the past, enabling us to connect with our ancestors and appreciate the rich tapestry of human history that spans millennia.

The proliferation of artistic activities in Upper Paleolithic Times

- Prehistoric paintings have been found in many parts of the world, and by the Upper Paleolithic times, there was a proliferation of artistic activities.

- Around the world, the walls of many caves from this time are full of finely carved and painted pictures of animals that the cave-dwellers hunted.

- The subjects of their drawings were human figures, human activities, geometric designs, and symbols.

- In India, the earliest paintings have been reported from the Upper Palaeolithic times.

Significance of Prehistoric Paintings

These prehistoric paintings help us to understand early human beings, their lifestyle, their food habits, their daily activities, and, above all, they help us understand their mind and the way they thought.

Discovery of Prehistoric Rock Paintings in India

- The first discovery of rock paintings in India was made in 1867–68 by an archaeologist, Archibold Carlleyle, twelve years before the discovery of Altamira in Spain. Cockburn, Anderson, Mitra, and Ghosh were the early archaeologists who discovered a large number of sites in the Indian subcontinent.

- Remnants of rock paintings have been found on the walls of caves situated in several districts of Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, and Bihar. Some paintings have also been reported from the Kumaon hills in Uttarakhand.

Categories of Paintings

- The rock shelters on the banks of the River Suyal at Lakhudiyar, about twenty kilometers on the Almora– Barechina road, bear these prehistoric paintings. Lakhudiyar means one lakh caves.

- The paintings here can be divided into three categories: man, animal, and geometric patterns in white, black, and red ochre.

- Humans are represented in stick-like forms. A long-snouted animal, a fox, and a multiple-legged lizard are the main animal motifs. Wavy lines, rectangle-filled geometric designs, and groups of dots can also be seen here.

- One of the interesting scenes depicted here is of hand-linked dancing human figures. The granite rocks of Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh provided suitable canvases to the Neolithic man for his paintings. There are several such sites, but more famous among them are Kupgallu, Piklihal, and Tekkalkota.

Evolution of Prehistoric Paintings

Upper Paleolithic Period

- The paintings of the Upper Palaeolithic phase are linear representations, in green and dark red, of huge animal figures, such as bison, elephants, tigers, rhinos, and boars, besides stick-like human figures.

- Most paintings consist of geometrical patterns. The green paintings are of dancers and the red ones of hunters.

- The largest and most spectacular rock shelter is located in the Vindhya hills at Bhimbetka in Madhya Pradesh.

- The caves of Bhimbetka were discovered in 1957–58 by eminent archaeologist S. Wakankar.

- The themes of paintings found here range from mundane events of daily life in those times to sacred and royal images.

Mesolithic Period

- The largest prehistoric paintings discovered in India belong to this period. During this period, the themes multiply, but the paintings are smaller in size.

- Hunting scenes predominate. The hunters are shown wearing simple clothes and ornaments.

- In some paintings, men have been adorned with elaborate head-dresses, and sometimes painted with head masks.

- In the pre-historic paintings found in India, animals are depicted in their naturalistic style, while human beings are depicted stylistically.

- Prominent Mesolithic sites where these paintings are found include Langhnaj in Gujarat, Bhimbetka, and Adamagarh in Madhya Pradesh, and SanganaKallu in Karnataka.

Chalcolithic painting

- The paintings of the Chalcolithic period reveal the association, contact, and mutual exchange of requirements of the cave dwellers of this area with settled agricultural communities of the Malwa plains.

- Many times, Chalcolithic ceramics and rock paintings bear common motifs, such as cross-hatched squares, lattices, pottery, and metal tools.

- The primitive artists used many colors, including various shades of white, yellow, orange, red ochre, purple, brown, green, and black.

- Red was obtained from haematite (geru), green from a green variety of a stone called chalcedony, and white might have been made out of limestone. To make the paint, the rock or mineral was first ground into a powder, which was then mixed with water and a thick or sticky substance such as animal fat gum or resin from trees. Brushes were made of plant fiber.

- The colors have remained intact because of the chemical reaction of the oxide present on the surface of the rocks.

- The pre-historic paintings found in India are unique in their depiction of both men and animals engaged in the struggle for survival.

- The paintings of individual animals show the mastery of the skill of the primitive artist in drawing these forms.

- Both proportion and tonal effect have been realistically maintained in them.

- These paintings have survived for such a long period due to the natural conditions of the caves, such as a lack of light and moisture, and also because of the chemical reaction of the oxide present on the surface of the rocks.

- More animal figures than human figures are depicted in cave paintings probably because animals played a significant role in the lives of prehistoric humans.

- Animals were sources of food, clothing, and other essential resources.

- Therefore, prehistoric humans would have observed and studied the behavior of animals closely, leading to their depiction in cave paintings. Additionally, animals may have been seen as powerful and awe-inspiring, leading to their frequent depiction in cave paintings.

Sculptures of the Harappan Civilization hold a significant role in understanding the lifestyle of the Harappan people. It also helps historians to understand the civilization further.

Sculptures of the Harappan Civilization

- During the second millennium, the arts of the Indus Valley civilization, one of the world’s first civilizations, arose. Sculptures, seals, ceramics, gold jewelry, terracotta figurines, and other types of art have been discovered at many civilization sites.

- Their renderings of human and animal forms were extremely lifelike and the modeling of figures was done with utmost caution.

- The major materials used for sculptors were: Stone, Bronze, Terracotta, Clay, etc.

Stone Sculptures of Harappan Civilization

The handling of the 3-Dimensional volume may be seen in stone figures found in Indus valley sites. There are two major stone statues:

- In Mohenjo-Daro, a Bearded Man (Priest Man, Priest-King) was discovered. The main features of the figure were:

- Steatite figurine of a bearded guy.

- The figure is covered in a shawl that comes under the right arm and covers the left shoulder, indicating that it is a priest. The shawl has a trefoil design on it.

- As in contemplative concentration, the eyes are extended and partially closed.

- The nose is well-formed and of average size.

- Short beard and whiskers, as well as a short moustache.

- A basic woven fillet is carried around the head once the hair is separated in the center.

- A right-hand armlet and holes around the neck imply a necklace.

- Overall, there is a hint of the Greek style in the statues.

Bearded Priest

- Male Torso

- Red sandstone was used to create it.

- The head and arms are attached to the neck and shoulders through socket openings. Legs have been broken.

- The shoulders are nicely browned, and the belly is a little protruding.

- It is one of the more expertly cut and polished pieces.

Bronze Sculptures of Harappan Civilization

- Bronze casting was conducted on a large scale in practically all of the civilization’s main sites.

- Bronze casting was done using the Lost Wax Technique.

Lost Wax Technique

- At first, the required figure is formed of wax and coated with clay. After allowing the clay to dry, the entire assembly is heated to melt the wax within the clay. The melted wax was then drained out of the clay section through a small hole.

- The molten metal was then poured into the hollow clay mold. The clay coating was fully removed once it had cooled.

- The Bronze casting includes both human and animal representations.

- The buffalo, with its raised head, back, and sweeping horns, and the goat, among animal representations, are aesthetic assets.

- Bronze casting was popular at all locations of Indus valley culture, as evidenced by the copper dog and bird of Lothal and the Bronze figure of a bull from Kalibangan.

- Metal casting persisted until the late Harappan, Chalcolithic, and other peoples following the Indus valley civilization.

Examples of Bronze Casting are:

Dancing Girl

- Founded in Mohenjo-Daro, is one of the best-known artifacts from Indus valley.

- It depicts a girl whose long hair is tied in a bun and bangles cover her left arm.

- Cowry shell necklace is seen around her neck with her right hand on her hip and her left hand clasped in a traditional Indian dance gesture.

Dancing Girl

Bull from Mohenjo-Daro

- Mohenjo-Daro has a bronze statue of a bull.

- The bull’s massiveness and the charge’s wrath are vividly depicted.

- The animal is seen standing to the right with his head cocked.

- A cord is wrapped around the neck.

Terracotta Sculptures of Harappan Civilization

- In Gujarat and Kalibangan, terracotta statues are more lifelike.

- A few figures of bearded males with coiled hairs are found in terracotta, their stance firmly erect, legs slightly apart, and arms parallel to the sides of the torso. The fact that this figure appears in the same posture over and over again suggests that he was a divinity.

- There was also a clay mask of a horned god discovered.

- Terracotta was also used to create toy carts with wheels, whistles, rattles, birds and animals, gamesmen, and discs.

- Mother Goddess figurines are the most important clay figures.

The main example of a terracotta figure is:

Mother Goddess

- Mohenjo-Daro is where it was found.

- These are mainly crude standing figurines.

- Wearing a loin robe and a grid, she is adorned with jewelry dangling from her large breast.

- The mother goddess’s distinctive ornamental element is her fan-shaped headpiece with a cup-like protrusion on either side.

Mother Goddess

- The figure’s pellet eyes and beaked snout are exceedingly primitive (constructed in a rudimentary way).

- A tiny hole indicates the mouth.

Conclusion

The artists and craftsmen of the Indus Valley were extremely skilled in a variety of crafts—metal casting, stone carving, making and painting pottery, and making terracotta images using simplified motifs of animals, plants, and birds, making the civilization a rich one.

The Harappan civilization’s town layout supports the idea that the city’s municipal establishments were well developed. The Indus Valley civilization is distinguished by its town layout. Their town layout demonstrates that they had a civilised and evolved life. In nature, town planning was fantastic. A few towns feature citadels to the west built on higher platforms, with residential areas to the east. They are both enclosed by a large masonry wall. Cities without a fortress are built on towering mounds.

Town Planning & Structures

- The Harappan civilisation was characterised by its grid-based town planning system, in which streets and alleys cut across one another virtually at right angles, separating the city into many rectangular blocks.

- Harappa, Mohenjodaro, and Kalibangan each had their own castle erected on a high mud-brick pedestal.

- Each city has a lower town with brick buildings occupied by the ordinary people beneath the castle.

- The Harappan civilisation is distinguished by the widespread use of burned bricks in practically all types of architecture and the lack of stone structures.

- Another notable feature was the underground drainage system that connected all dwellings to street drains that were covered by stone slabs or bricks.

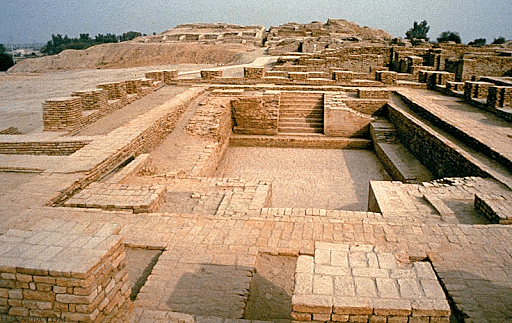

- The Great Bath, which is 39 feet long, 23 feet wide, and 8 feet deep, is Mohenjodaro’s most significant public space.

- A flight of steps leads to the surface at each end. There are separate dressing rooms. The Bath’s floor was constructed of charred bricks.

- The biggest structure at Mohenjodaro is a granary 150 feet long and 50 feet wide.

- However, there are as many as six granaries in Harappa’s fortress.

Features

Streets and Roads

- Indus Valley’s streets and roadways were all straight and intersected at a right angle.

- All of the roadways were constructed with burned bricks, with the length of each brick being four times its height and the breadth being two times its height.

- They ranged in width from 13 to 34 feet and were fully lined.

- The city was split into rectangular blocks by the streets and roadways.

- Archaeologists unearthed the lamp posts at regular intervals. This implies the presence of street lighting.

- On the streets, there were also trash cans. These demonstrate the presence of competent municipal management.

Streets of Indus Valley Civilization

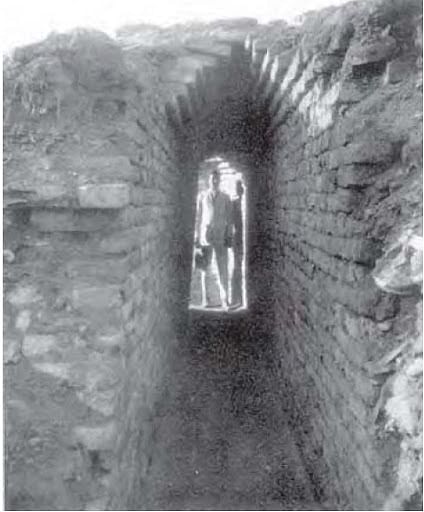

Drainage system

- One of the most notable elements of the Indus Valley civilization was the city’s efficient closed drainage system.

- Cities of the Indus Valley Civilization possessed sophisticated water and sewage systems.

- Many Indus Valley sites have houses with single, double, and more rooms coupled to a very effective drainage system.

- Each residence had its own drainage and soak pit that was linked to the public drainage system.

- Every roadway was lined by brick-paved canals.

- They were covered and had manholes at regular intervals for cleaning and clearing.

- To convey extra water, large brick culverts with corbelled roofs were built on the city’s outskirts.

- As a result, the Indus people developed a flawless subsurface drainage system.

- No other modern culture paid such close attention to hygiene.

- Corbelled drains were the primary method of collecting waste and rainfall; they may also have been used to empty enormous pools used for ceremonial washing.

A drain in Mohenjodaro

Great bath

- The Great Bath is the most notable feature of Mohenjodaro. It is made up of a big quadrangle.

- The discovery reveals that the Great Bath, which was located within the city, was a huge rectangular tank used for special rites or ceremonial bathing and resembled a modern-day swimming pool.

- There is a large swimming pool in the centre (about 39 feet long, 23 feet wide, and 8 feet deep) with the ruins of galleries and chambers on all four sides.

- It features a flight of stairs at either end and is supplied by a well in one of the neighbouring apartments.

- The water was released through a massive drain with a corbelled ceiling that was more than 6 feet deep.

- The Great Bath’s outside walls were 8 feet thick.

- To prevent water leakage, the tank was covered with gypsum.

- For 5000 years, this sturdy structure has resisted the assaults of nature.

- Some rooms were equipped with hot water baths.

The Great Bath source

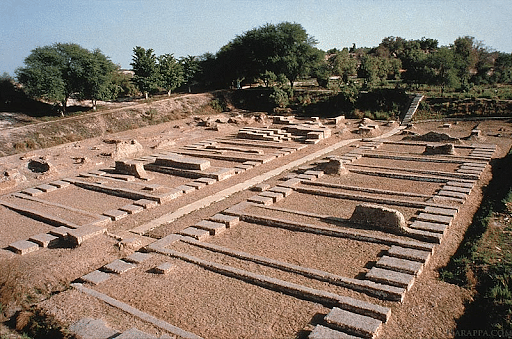

Granaries

- The granary, which is 45.71 metres long and 15.23 metres broad, is the biggest structure at Mohenjodaro.

- Harappa has a set of brick platforms that served as the foundation for two rows of six granaries each.

- Brick platforms have also been discovered in the southern section of Kalibangan.

- These granaries protected the grains, which were most likely gathered as income or as storehouses to be used in crises.

- During disasters, most staple foods like rice, wheat, and barley were stockpiled in these warehouses for public distribution.

- The cervical granaries were a massive building.

- Archeological evidence suggests that the lowest half of the stockroom was formed of blocks, while the upper part was most likely made of wood.

Granaries of Harappan Civilization

Buildings

- People from the Indus Valley civilisation erected dwellings and other structures beside highways.

- They constructed terraced dwellings out of charred bricks. Every dwelling had at least two rooms.

- There were also multi-story buildings.

- The buildings were built around an inner courtyard and had pillared hallways, bath rooms, paved floors, a kitchen, a well, and other amenities.

- In addition to living quarters, extensive constructions have been discovered.

- One of these structures has the largest hall, which is 80 feet long and 80 feet broad.

- It might have been a castle, a temple, or a meeting hall.

- There are also workmen’s quarters. It had an outstanding water supply system. There were public wells throughout the streets.

- Each large residence has its own well.

- They also constructed a dockyard at Lothal.

- The majority of the residences in the Lower Town featured a central courtyard surrounded by rooms.

- Summer activities like cooking and knitting were most likely done in the courtyard.

- To promote privacy, the main entrance was usually located so that it did not provide a direct view of the inside.

- Furthermore, there were no windows on the ground-level walls of the dwellings.

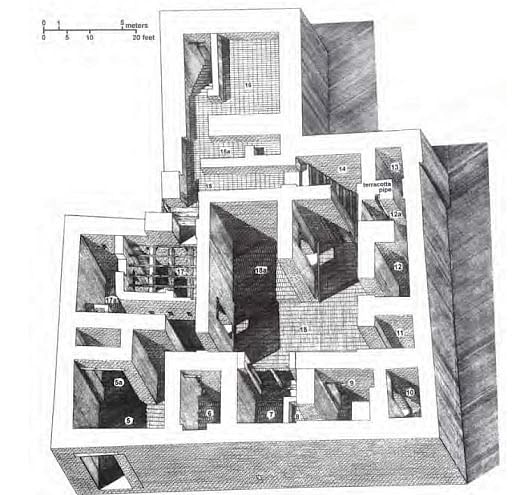

An isometric drawing of a large house in Mohenjodaro

Conclusion

The Indus Valley Civilization was one of the world’s oldest and most advanced civilizations. The cities were well-planned and developed. Waste collection and disposal were also done in a lovely way, as a wooden screen was put at the end of the main sewer, demonstrating that they were also concerned about water contamination. Streets were also built in an engineering manner, using burnt bricks and a well-drained system.