Ancient History – 2nd Year

Paper – II (Short Notes)

Unit I

Language/भाषा

The Gupta Empire, spanning from approximately 320 to 550 CE, is often celebrated as the “Golden Age” of India due to its remarkable advancements in culture, science, and political stability. This era is significant for its flourishing of art, literature, and scientific achievements, which laid the foundation for future developments in Indian history.

About Gupta Empire

- The Gupta Empire was an ancient Indian empire founded by Sri Gupta. It stretched across northern, central, and southern parts of India between 320 and 550 CE.

- The Gupta Empire is called the Golden Age of India due to its achievements in the arts, architecture, sciences, religion, and philosophy.

- During this Gupta Empire, India witnessed a renaissance in cultural and intellectual pursuits, with significant contributions from figures like Kalidasa in literature and Aryabhata in science.

- The Gupta rulers fostered an environment of stability and prosperity, facilitating advancements in various fields and leaving a lasting legacy on Indian civilisation.

History of Gupta Empire

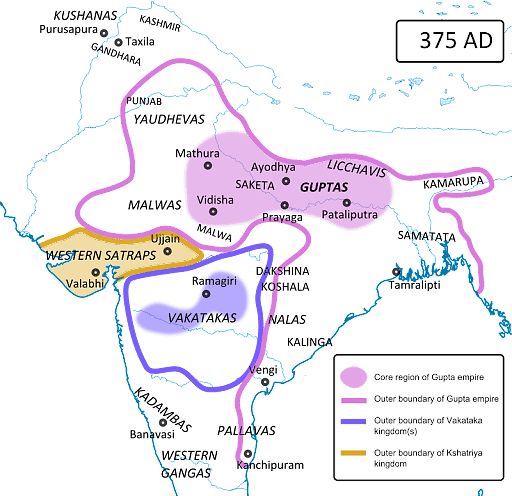

- At the beginning of the fourth century A.D., no powerful empire existed in India.

- Both the Satavahanas and the Kushans, who had emerged as major political powers in the Deccan and the North, respectively, after the breakup of the Mauryan Empire, ended in the middle of the third century A.D.

- Several minor powers occupied the political space, and some new ruling families were emerging.

- Against this backdrop, the Guptas, a family of uncertain origins, began to build an empire at the beginning of the fourth century A.D.

- The ancestry and early history of the Gupta family are little known and have naturally given rise to various speculations. Various historians have given different ancestry to the Guptas, like Vaishya, Brahmins, Kshatriyas, Ikshvaku clan etc.

- At the end of the third century A.D., the original kingdom of the Guptas comprised Uttar Pradesh and Bihar. However, Uttar Pradesh seems to have been a more important province for the Guptas than Bihar because early Gupta coins and inscriptions were mainly found in that state.

- As per the inscriptions, Sri Gupta was the founder of the Gupta dynasty, and Ghatotkacha was the next to follow him. Chandragupta was the first independent ruler.

Capital of Gupta Empire

- The Gupta Empire’s capital was Pataliputra, in present-day Patna, Bihar.

- The Gupta Empire was a central political, economic, and cultural hub during the Gupta period.

- Known for its strategic location at the confluence of the Ganges and Son rivers, Pataliputra was a thriving centre of administration and trade, facilitating the growth and prosperity of the Gupta Empire.

- The city’s significance was further enhanced by its role in promoting learning and artistic achievements, which flourished under Gupta rule.

Founder of Gupta Empire

- The founder of the Gupta Empire was Chandragupta I, who ascended to the throne around 320 CE.

- Chandragupta I established the Gupta dynasty and laid the foundation for a golden age in Indian history.

- His reign marked the beginning of significant advancements in various fields, including science, art, and literature, setting the stage for the empire’s expansion and prosperity under his successors.

Rulers of Gupta Empire

- The Gupta Empire was ruled by powerful and influential monarchs who established a golden age in Indian history.

- The rulers of the Gupta Empire were known for their effective governance, military prowess, and patronage of the arts and sciences.

- Their reign marked a period of significant economic prosperity, cultural development, and political stability, which laid the foundation for the flourishing civilisation of the Gupta Empire.

- The contributions of the Gupta Empire were instrumental in shaping the cultural and intellectual landscape of the time.

Chandragupta I (C. 319-335 AD)

- Chandragupta-I was the son of Ghatotkacha and is considered the real founder of the Gupta Empire.

- He married the Lichchhavi princess named Kumara Devi.

- After declaring his independence in Magadha, he enlarged his kingdom with the help of a matrimonial alliance with the Lichchhavis.

- There needs to be concrete evidence to determine the boundaries of his kingdom. However, it is assumed that it covered parts of Bihar, U.P., and Bengal.

- Chandragupta-I is also said to have started a new era from 319 to 320 A.D., which marked the date of his accession. This era came to be known as the Gupta Samvat or Gupta era.

- During the times of his son Samudragupta, the kingdom grew into an empire.

Samudragupta (335-380 AD)

- Chandragupta-I’s son and successor, Samudragupta, enlarged the Gupta kingdom enormously.

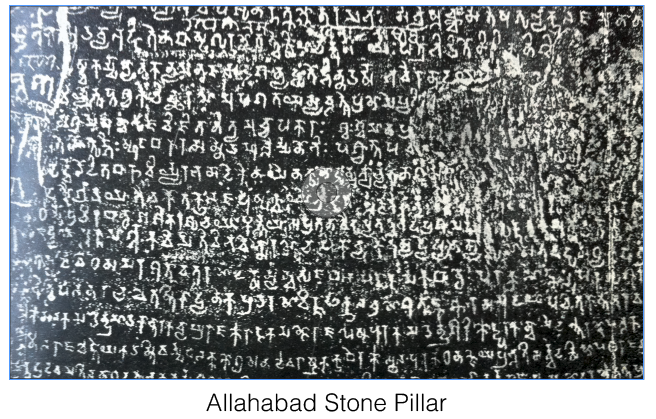

- His court poet Harishena wrote a glowing account of his military exploits. In a long inscription engraved at Allahabad, the poet enumerates the peoples and countries that were conquered by Samudragupta.

- Harishena also referred to him as Kaviraj, which meant that he was not only a patron of poetic arts but also a poet himself. Samudragupta also assumed the title of Vikramanka.

- He performed Ashvamedha Yajna, the first Ashvamedha Yajna after Pushyamitra Shunga.

- The places and the countries conquered by Samudragupta can be divided into five groups.

- Samudragupta’s prestige and influence spread even outside India. According to a Chinese source, Samudragupta granted permission to Ceylon king Meghavarman to build a Buddhist monastery at Bodhgaya.

- According to the inscription at Allahabad, Samudragupta never experienced defeat, and in this sense, he is called the Napoleon of India.

- Samudragupta unified the greater part of India under him, and his power was felt in a much larger area.

- Samudragupta laid the military foundations of the Gupta empire, and his successors built upon these foundations.

- Prithivyah Pratham Veer was the title of Samdudragupta.

Chandragupta II (C. 380 – C. 415 CE)

- The reign of Chandragupta II saw the high watermark of the Gupta Empire. He extended the limits of the empire through marriage, alliance, and conquest.

- The Gupta inscriptions mention Chandragupta-II as Samudragupta’s successor.

- However, based on literary sources, some copper coins, and inscriptions, it is suggested that the successor was Samudragupta’s other son, Ramagupta. Visakhadatta’s drama “Devichandraguptam” mentions that Chandragupta-II killed his elder brother Ramagupta and ascended the throne.

- Chandragupta II entered into matrimonial alliances with the Nagas by marrying Princess Kuberanaga, whose daughter Prabhavati was later married to Rudrasena-II of the Vakataka family. Thus, Chandragupta exercised indirect control over the Vakataka kingdom in central India.

| The Story of Devi Chandragupatam |

| – It is mentioned in the drama that Ramagupta was facing defeat at the hands of the Sakas, and to save the kingdom, he had agreed to surrender his wife to the Saka king. – Chandragupta protested and went to the Saka camp disguised as queen Dhruvadevi. He was successful against the Saka king, but as a result of the subsequent hostility with his brother, he killed him and married his wife, Dhruvadevi. – Specific other texts, like the Harsacharita, Kavyamimansa, etc., also refer to this episode. – Some copper coins bearing the name Ramagupta have also been found, and inscriptions on the pedestals of some Jaina images found at Vidisa bear the name Maharaja Ramgupta. – Similarly, Dhruvadevi is described as the mother of Govindagupta (Chandragupta’s son) in a Vaisali seal. |

- Due to his control over the Vakataka kingdom, Chandragupta II conquered western Malwa and Gujarat, which had been under the Sakas’ rule for about four centuries.

- The conquest of Sakas was the most important event of Chandragupta-II’s reign. He destroyed the Saka chieftain Rudrasena III and annexed his kingdom.

- The conquest gave Chandragupta the western sea coast, which was famous for trade and commerce. This contributed to the prosperity of Malwa and its chief city, Ujjain, which seems to have been Chandragupta II’s second capital.

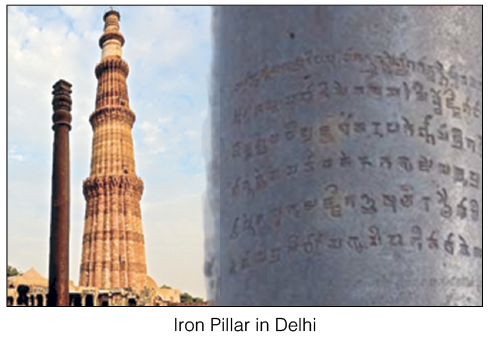

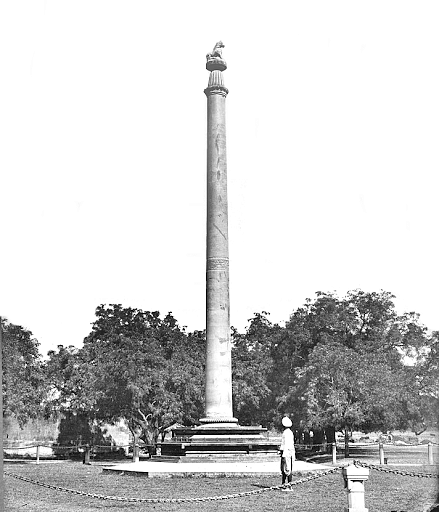

- Chandragupta-II is identified with “King Chandra,” whose exploits are mentioned in the Mehrauli Iron Pillar in the Qutab Minar complex in Delhi.

- According to this inscription, Chandra crossed the Sindhu region of seven rivers and defeated Valhikas (who were identified as Bactria). Some scholars identify Chandragupta-II with the hero of Kalidasa’s work “Raghuvamasa” because Raghu’s exploits appear comparable with those of Chandragupta.

- The Mehrauli inscription also mentions Chandragupta’s victory over enemies from Vanga (Bengal).

- Chandragupta II adopted the title of “Vikramaditya”, which had been first used by a Ujjain ruler in 58 B.C. as a mark of victory over the Sakas.

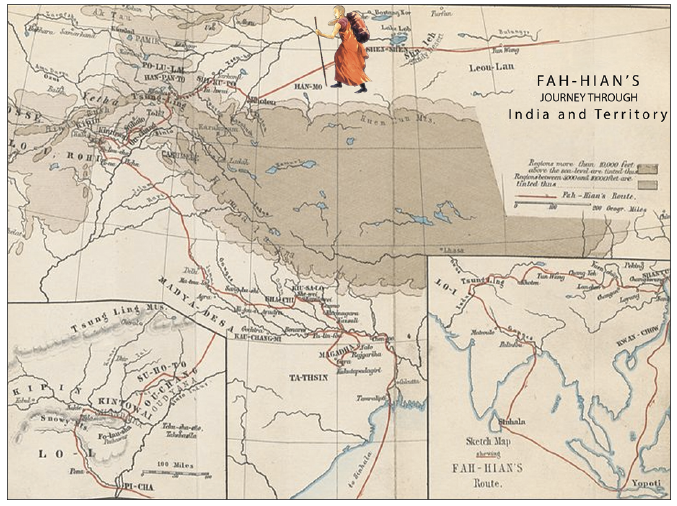

- The Chinese pilgrim Fa-Hsien (399-414) visited India during Chandragupta’s time and wrote an elaborate account of the people’s lives.

- In his memoirs, he vividly describes the places he visited and the specific social and administrative aspects related to them.

- However, he does not mention the king’s name in his accounts. He speaks highly of the King of Madhya-desa, the region directly ruled by the Gupta monarch in this period.

- Numerous scholars adorned Chandragupta II’s court at Ujjain, collectively known as the Navratnas, or the nine gems.

- Chandragupta II was the first ruler to assume the ‘Param Bhagvat’ title.

Kumaragupta I (415 – 455 AD)

- Chandragupta-II was succeeded by his son Kumaragupta also known as Mahendraditya.

- The Damodarpur Copper Plate inscriptions (433 A.D. and 447 A.D.) refer to him as Maharajadhiraja and show that he appointed the governor (Uparika) of Pundravardhana bhukti (or province) being the biggest administrative division in the empire.

- The last known date of Kumaragupta is from a silver coin dated 455 A.D. (Gupta Era 136).

- The wide area over which his inscriptions are distributed indicates that he ruled over Magadha and Bengal in the east and Gujarat in the west.

- It has been suggested that in the last year of his reign, the Gupta Empire faced a foreign invasion (a Hun invasion), which was checked by the efforts of his son Skandagupta.

- He maintained a cordial relationship with the Vakatakas, established through matrimonial alliances earlier.

- He established the Nalanda University in Bihar.

Skandagupta (455 – 467 AD)

- Skandagupta, who succeeded Kumaragupta-I, was the last powerful Gupta monarch. He assumed the titles of Vikramaditya, Devaraj and Sakapan.

- Skandagupta’s most significant achievement was defeating the Pushyamitras and throwing back the Huns, who had troubled the Gupta Empire since his father’s reign.

- These wars adversely affected the empire’s economy, and the gold coinage of Skandagupta bears testimony to that.

- Skandagupta minted fewer types of gold coins than earlier rulers. He appears to have been the last Gupta ruler to mint silver coins in western India.

- However, the Junagadh inscription of his reign tells us about the public works undertaken during his times.

- The Sudarsana lake (originally built during the Mauryan times) burst due to excessive rains, and his governor, Pamadatta, repaired it.

- This indicates that the state undertook the task of public works.

- The last known date of Skandagupta is 467 A.D. from his silver coins.

Later Guptas

- There is not much clarity on the order of successors of Skandagupta.

- The division of the Gupta Empire into many parts had already begun towards the close of Skandagupta’s reign.

- Thus, an inscription from western Malwa, recorded in Skandagupta’s last year, does not refer to him but to some other rulers beginning with Chandragupta-II.

- Inscriptions mention some of Skandagupta’s successors: Budhagupta, Vainyagupta, Bhanugupta, Narasimhagupta Baladitya, Kumaragupta-II, and Vismigupta.

- It is unlikely they all ruled over a vast empire, as Chandragupta-II and Kumaragupta-I had done earlier.

- The Guptas continued to rule until about 550 A.D., but by then, their power had already become insignificant.

Polity & Administration of Gupta Empire

The polity and administration of the Gupta Empire are as follows:

- Decentralisation and Devolution of Power: The king was advised by a Council of Ministers, responsible for various administrative and military duties.

- A range of ministers and officials managed military and other affairs under the king’s direction.

- The Gupta Empire did not have an overly elaborate bureaucracy due to the effective decentralisation of administrative authority through land grants and friendly Samanta contracts with subdued neighbours.

- Samanta System: The power was devolved to various authorities, giving rise to political hierarchies.

- This is evidenced by the Allahabad Pillar Inscription, which notes that Samudragupta did not kill or destroy his enemies but brought them under suzerainty.

- In the Gupta Empire, a Samanta was a neighbouring subsidiary ruler, a friendly tributary of the Gupta overlords.

- Land Grants: Decentralization was also effected via various land grants, which granted persons and institutions varied immunities and concessions.

- This is one reason that, unlike the Mauryan period, the Gupta Empire had a manageable bureaucracy.

- The Gupta Empire administration was highly centralised. The king was at the top, wielding absolute power but often guided by a council of ministers.

- The Gupta empire was divided into provinces called Bhuktis, each governed by a Uparika or provincial governor and further subdivided into Vishayas (districts) managed by officials called Vishayapatis.

- Local administration involved village assemblies, which were essential in managing local affairs.

- The Guptas maintained a strong bureaucratic system and relied on feudal lords and guilds for regional governance and tax collection. This system contributed to the Gupta empire’s long-lasting stability and prosperity.

Economy of Gupta Empire

The developments in the economy of the Gupta Empire is as follows:

- The economy during the Gupta period was characterised by flourishing trade, a well-functioning guild system, flourishing manufacturing industries, and a high standard of living.

- Of course, agriculture was the main occupation of the people, but other occupations, like commerce and the production of crafts, had become specialized occupations in which different social groups were engaged.

Guild System of Gupta Empire

- A guild is an association of artisans or merchants who oversee the practice of their craft in a particular area.

- In Gupta Era, the activities of Guilds increased considerably. Guilds came to acquire considerable autonomous power. These trade guilds were both politically and economically influential.

- Guilds could control one trade in a province and wield economic dominance. Moreover, they became politically influential and also started maintaining militias.

Science and Technology of Gupta Empire

The developments in the science and technology of the Gupta Empire are as follows:

- Gupta science and technology witnessed remarkable advancements, marking the period as a golden age of intellectual development in ancient India.

- Scholars like Aryabhata and Varahamihira made significant contributions to mathematics and astronomy, with Aryabhata’s work on zero and the decimal system being particularly influential.

- In medicine, Sushruta and Charaka authored seminal texts on surgery and herbal medicine.

- The period also saw advancements in metallurgy, exemplified by the Iron Pillar of Delhi, which showcased sophisticated metalworking techniques.

- These innovations reflect the Gupta era’s profound impact on scientific and technological progress.

Society in Gupta Empire

The developments in the society of the Gupta Empire are as follows:

- Chandragupta II was a patron of art and literature. Samudragupta is represented on his coins playing the veena, and Chandragupta II is credited with maintaining nine luminaries or great scholars in his court.

- In ancient India, art was mainly inspired by religion. Few survivors of non-religious art from ancient India exist. Buddhism gave great impetus to art in the Mauryan and post-Mauryan periods.

- It led to the creation of massive stone pillars, the cutting of beautiful caves and the raising of high stupas or relic towers.

- The stupas appeared as dome-like structures on round bases mainly of stone—numerous images of the Buddha.

Art and Architecture of Gupta Empire

The developments in the art and architecture of the Gupta Empire are as follows:

- Gupta art and architecture represent a pinnacle of classical Indian artistic expression, characterised by refinement and grandeur.

- Gupta sculpture is renowned for its elegant, graceful forms and intricate detailing, exemplified in works such as the Ajanta and Ellora Caves and the Udayagiri Caves.

- The period is marked by the development of temple architecture, with the emergence of the Nagara style, characterised by its curvilinear shikhara (spire).

- In the Ajanta Caves, Gupta paintings display vibrant colours and intricate narratives of Buddhist Jataka tales.

- The era’s art and architecture reflected the cultural and religious dynamism of the time and laid the foundations for subsequent artistic traditions in India.

Literature of Gupta Empire

The developments in the literature of the Gupta Empire are as follows:

- Gupta literature flourished during the Gupta period (c. 320–550 CE) and is renowned for its contributions to Sanskrit literature and drama.

- Classical Sanskrit literature saw significant development, with notable figures like Kalidasa, who penned masterpieces such as Shakuntala and Meghaduta, showcasing the richness of poetic and dramatic expression.

- The era also saw the creation of important epic and devotional texts, including portions of the Mahabharata and Ramayana, as well as philosophical works by authors like Aryabhata.

- Gupta literature is characterised by its use of sophisticated language, intricate poetic forms, and thematic diversity, reflecting the cultural and intellectual vibrancy of the period.

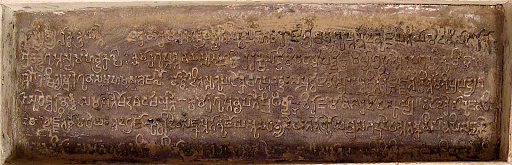

Inscriptions of Gupta Empire

The developments in the literature of the Gupta Empire are as follows:

- Gupta inscriptions are crucial historical sources from the Gupta period (c. 320–550 CE), offering insights into the era’s administration, culture, and religious practices.

- Inscribed on various materials such as stone, copper plates, and pillars, these inscriptions document royal edicts, land grants, and religious dedications.

- Notable examples include the Allahabad Pillar Edict of Samudragupta, which celebrates his military conquests and accomplishments.

- Gupta inscriptions provide valuable information about the Gupta empire’s political and social organization, the spread of Hinduism, and the administrative practices of the Gupta rulers.

Decline of Gupta Empire

Towards the end of the 6th century, the Gupta Empire began falling. Some of the salient factors that contributed towards the disintegration of the Gupta empire are as follows:

- Huna Invasions: The successors of Chandragupta II had to face an invasion by the Hunas from Central Asia in the second half of the fifth century A.D.

- Although the Gupta king Skandagupta initially tried effectively to stem the march of the Hunas into India, his successors proved to be weak. They could not cope with the Huna invaders, who excelled in horsemanship and possibly used metal stirrups.

- They could move quickly, and being excellent archers, they seem to have attained considerable success in Iran and India.

- Administrative Weaknesses: The Gupta Empire’s policy in conquered areas was to restore the authority of local chiefs or kings once they had accepted Gupta suzerainty.

- No efforts were made to impose strict and effective control over these regions.

- Hence it was natural that whenever there was a crisis of succession or a weak monarchy within the Gupta empire, these local chiefs would re-establish their independent authority.

- This created a problem for almost every Gupta King who had to reinforce his authority.

- The constant military campaigns were a strain on the state treasury.

- Towards the end of the fifth century A.D. and beginning of sixth century A.D. taking advantage of the weak Gupta emperors, many regional powers reasserted their authority and in due course, declared their independence.

- Rise of the Feudatories: The Gupta empire was further undermined by the increase of the feudatories.

- The governors appointed by the Gupta kings in north Bengal and their feudatories in Samatata or south-east Bengal tended to become independent.

- Issuance of Land Grants: The Gupta Empire may have found it dificult to maintain a large professional army due to the growing practice of land grants for religious and other purposes, which was bound to reduce its revenues.

- Decline in Trade: Their income may have further been affected by the decline of foreign trade.

- The migration of a guild of silk weavers from Gujarat to Malwa in A.D. 473 and their adoption of non-productive professions show that there was little demand for the cloth they produced.

- Besides the reasons quoted above, divisions within the imperial family, concentration of power in the hands of local chiefs or governors, and a loose administrative structure contributed to the disintegration of the Gupta empire.

Importance of Gupta Empire

The importance of the Gupta Empire can be seen as follows:

- The Gupta Empire was one of the world’s largest political and military empires. It was ruled by members of the Gupta dynasty from around 320 to 600 CE and covered most parts of Northern India.

- The peace and prosperity established during the reign of the Gupta rulers enabled the pursuit of scientific and artistic endeavours.

- Significant achievements were made in the arts, literature, and religion. Sanskrit poetry, drama, and art grew in importance, resulting in the Gupta period being known as the classical age of Indian culture and arts.

- Major scientific advances were realized in astronomy, medicine, and mathematics. The decimal system of numerals, which included the concept of zero, was developed.

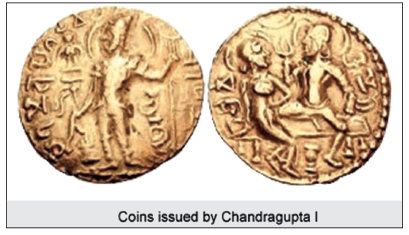

King Chandragupta I of the Gupta Empire ruled over northern India between the years 319 and 334 CE. He may have been the dynasty’s first emperor, as suggested by his title Maharajadhiraja (“great king of kings”). The exact process by which he expanded his small hereditary kingdom into an empire is unknown, but a widely accepted hypothesis among contemporary historians holds that it was made possible by his union with Kumaradevi, a Licchavi princess, who served as a political ally. Samudragupta, their son, strengthened the Gupta empire much further.

Chandragupta I

- Chandragupta was the son of Gupta king Ghatotkacha and the grandson of Gupta, the founder of the dynasty, both of whom are referred to as Maharaja (“great king”) in the Allahabad Pillar inscription.

- Chandragupta assumed the title Maharajadhiraja and issued gold coins, implying that he was the dynasty’s first imperial ruler.

- Chandragupta ruled in the first quarter of the fourth century CE, but the precise period of his reign is unknown.

- His assumption of the title Maharajadhiraja has led to speculation that he established the Gupta calendar era, with the epoch of this era marking his coronation.

- Chandragupta I most likely reigned for a long time, as the Allahabad Pillar inscription indicates that he appointed his son as his successor, presumably after reaching old age. However, the precise duration of his reign is debatable.

Maharajadhiraja Chandragupta’s inscription, in the Samudragupta inscription on the Allahabad pillar

Marriage to Kumaradevi

- Chandragupta married Kumaradevi, a Lichchhavi princess. The name Licchavi refers to an ancient clan that was headquartered in Vaishali, present-day Bihar, during the time of Gautama Buddha.

- In the first millennium CE, a Lichchhavi kingdom existed in modern-day Nepal. The identity of Kumaradevi’s Lichchhavi kingdom, on the other hand, is unknown.

- According to an 8th-century inscription of Nepal’s Lichchhavi dynasty, their legendary ancestor Supushpa was born in the royal family of Pushpapura, that is, Pataliputra in Magadha. According to some historians, the Lichchhavis ruled Pataliputra during the reign of Samudragupta.

- However, according to this inscription, Supushpa ruled 38 generations before the 5th-century king Manadeva, or centuries before Chandragupta’s reign.

- As a result, even if the claim in this inscription is true, it cannot be taken as concrete evidence of Lichchhavi rule at Pataliputra during Chandragupta’s reign.

- Kumaradevi’s Lichchhavi kingdom is unlikely to have been located in modern-day Nepal because Samudragupta mentions Nepala (that is, Nepal) as a distinct, subordinate kingdom in his Allahabad Pillar inscription.

- Given the lack of other evidence, it is assumed that the Lichchhavis ruled at Vaishali during Chandragupta’s reign, as this is the only other base of the clan known from historical records.

A gold coin depicting Queen Kumaradevi and King Chandragupta I

Impact of the Alliance

- The gold coins attributed to Chandragupta have portraits of Chandragupta and Kumaradevi on them, as well as the legend Lichchhavayah (“the Lichchhavis”).

- In the Gupta inscriptions, their son Samudragupta is referred to as Lichchhavi-dauhitra (“Lichchhavi daughter’s son”).

- Except for Kumaradevi, these inscriptions do not mention the paternal family of the dynasty’s queens, implying that Kumaradevi’s marriage to Chandragupta was significant to the Gupta family.

- It is also said that Chandragupta defeated the Lichchhavi kingdom, which was based in Vaishali, and that Kumaradevi married him as part of a peace treaty.

- It suggested that the Guptas regarded this marriage as prestigious simply because of the Lichchhavis’ ancient lineage.

- The Lichchhavis, on the other hand, are described as “unorthodox and impure” in the ancient text Manusamhita (vratya).

- As a result, it is unlikely that the Guptas proudly mentioned Samudragupta’s Lichchhavi ancestry in order to boost their social standing.

- Furthermore, it is unlikely that the Guptas allowed the Lichchhavis’ name to appear on the dynasty’s coins after defeating them.

- It is more likely that the marriage assisted Chandragupta in expanding his political power and dominions, allowing him to assume the title Maharajadhiraja.

- The appearance of the Lichchhavis’ name on coins is most likely symbolic of their contribution to the Gupta expansion of power.

- Chandragupta was most likely the ruler of the Lichchhavi territories after his marriage.

- Alternatively, the Gupta and Lichchhavi states may have united, with Chandragupta and Kumaradevi regarded as the sovereign rulers of their respective states until the reign of their son Samudragupta, who became the sole ruler of the united kingdom.

Extent of Kingdom

- Other than his ancestry, marriage, and the expansion of Gupta power, which is evident from his title Maharajadhiraja, little is known about Chandragupta.

- The size of Chandragupta’s kingdom is unknown, but it must have been much larger than that of the previous Gupta kings, as Chandragupta bore the title Maharajadhiraja.

- Based on information from the Puranas and the Allahabad Pillar inscription issued by his son Samudragupta, modern historians have attempted to determine the extent of his kingdom.

- Several kings were subjugated by Samudragupta, according to the Allahabad Pillar inscription. Several modern historians have attempted to determine the extent of the territory that he must have inherited from Chandragupta based on the identity of these kings.

- For example, because the king of the northern Bengal region is not mentioned among the kings subjugated by Samudragupta, these historians speculate that northern Bengal was a part of Chandragupta’s kingdom.

- However, such conclusions cannot be drawn with certainty because the identity of several of the kings subjected by Samudragupta is unknown.

- Nonetheless, the information contained in the inscription can be used to identify territories that were not part of Chandragupta’s kingdom.

- In the west, Chandragupta’s kingdom probably did not extend much beyond Prayaga (modern Prayagraj), as Samudragupta defeated the kings of present-day western Uttar Pradesh.

- In the east, Chandragupta’s kingdom did not include southern Bengal, because the Allahabad Pillar inscription mentions Samatata as a frontier kingdom in that region. Furthermore, the Delhi Iron Pillar inscription suggests that the Vanga kingdom in that region was conquered by the later king Chandragupta II.

- In the north, the Allahabad Pillar inscription mentions Nepala (modern-day Nepal) as a frontier kingdom.

- In the south, Chandragupta’s kingdom did not include the Mahakoshal region of Central India, as Samudragupta defeated the kings of the forest region, which is associated with this region.

Coinage

- Gold coins with portraits of Chandragupta and Kumaradevi have been discovered in Uttar Pradesh at Mathura, Ayodhya, Lucknow, Sitapur, Tanda, Ghazipur, and Varanasi; Bayana, Rajasthan; and Hajipur, Bihar.

- The obverse of these coins features portraits of Chandragupta and Kumaradevi, along with their names in Gupta script. The reverse depicts a goddess seated on a lion, with the legend “Li-ccha-va-yah” (“the Lichchhavis”).

- Various scholars believe that the gold coins bearing the portraits of Chandragupta and Kumaradevi were issued by Samudragupta to commemorate his parents, while others believe that the coins were issued by Chandragupta himself or even by the Lichchhavis.

- The identity of the woman depicted on the reverse of these coins is unknown. It is unlikely that she was a Gupta queen because the depiction of a female figure seated on a lion is typical of a goddess in Indian historical art.

- Some historians believe the goddess is Durga. Although Durga is frequently depicted as seated on a lion, this is not a unique attribute to her: Lakshmi has also been depicted as seated on a lion.

- For example, Hemadri’s works mention Simha-vahini (“having lion as her vahana”) Lakshmi, and images from Khajuraho depict Simha-vahini Gajalakshmi.

- Some scholars believe the goddess depicted on the coins is Lakshmi, the goddess of fortune and the wife of Vishnu.

- She may have appeared on coins as a symbol of the Guptas’ royal prosperity or as a symbol of their Vaishnavite affiliation, but this cannot be proven.

- The goddess could also have been a tutelary goddess of the Lichchhavis, whose name appears beneath her image, but this cannot be proven.

Obverse and Reverse Coin of Chandragupta

Successors

- According to the Allahabad Pillar inscription and the Eran stone inscription of Samudragupta, his father Chandragupta chose him as the next king.

- According to the Allahabad Pillar inscription, Chandragupta appointed him to “protect the earth,” implying that Chandragupta renounced the throne in his old age and named his son as the next king.

- The discovery of coins issued by a Gupta ruler named Kacha has sparked discussion about Chandragupta’s successor.

- One theory holds that Kacha was another name for Samudragupta. Another theory holds that Kacha was Samudragupta’s elder brother who succeeded their father Chandragupta.

Conclusion

Chandragupta I was the most notable ruler of this dynasty. He united Guptas with the Lichchhavis by marriage. He extended his dynasty from Magdha to Prayaga and finally to Saketa. He expanded his domain from the Ganga to Prayaga. In 335 CE, Samudragupta succeeded his father, Chandragupta I, and ruled for about 45 years.

Samudragupta was the emperor of the Gupta Empire in ancient India. Samudragupta, Chandragupta I’s son and successor, greatly expanded the Gupta kingdom. According to the description of Harisena in the inscriptions on the Allahabad Pillar, Samudragupta was a great warrior.

Coin of Samudragupta with Garuda Pillar

Features

- Samudragupta (r. 335/336–375 CE) was the second emperor of Ancient India’s Gupta Empire and one of the greatest rulers in Indian history.

- He greatly expanded his dynasty’s political and military power as the son of Gupta emperor Chandragupta I and the Licchavi princess Kumaradevi. His conquests laid the groundwork for the expansion of the Gupta Empire, a period dubbed the “Golden Age of India” by oriental historians.

- The Allahabad Pillar inscription, a prashasti (eulogy) written by his courtier Harishena, credits him with numerous military victories. It implies that he defeated several northern Indian kings and annexed their territories to his empire.

- He also marched along India’s south-eastern coast, reaching the Pallava kingdom. He also subjugated a number of frontier kingdoms and tribal oligarchies.

- His empire stretched from the Ravi River in the west to the Brahmaputra River in the east, and from the Himalayan foothills in the north to central India in the south-west; his tributaries included several rulers along the south-eastern coast.

- To demonstrate his imperial sovereignty, Samudragupta performed the Ashvamedha sacrifice and, according to his coins, remained undefeated.

- His gold coins and inscriptions indicate that he was a talented poet who also played music. His son Chandragupta II carried on his father’s expansionist policies.

Background

- The Gupta kings’ inscriptions are dated in the Gupta calendar era, which is generally dated to around 319 CE.

- However, the identity of the era’s founder is disputed, with scholars varyingly attributing it to Chandragupta I or Samudragupta.

- The Prayag Pillar inscription indicates that Chandragupta I had a long reign, as he appointed his son as his successor, presumably after reaching old age.

- However, the precise duration of his reign is unknown. Because of these factors, the start of Samudragupta’s reign is also uncertain.

During his Reign

- Samudragupta was the son of the Gupta king Chandragupta I and the Licchavi queen Kumaradevi.

- According to his father’s Eran stone inscription, he was chosen as the heir because of his “devotion, righteous conduct, and valour.”

- According to his Allahabad Pillar inscription, Chandragupta called him a noble person in front of the courtiers and appointed him to “protect the earth.”

- According to these accounts, Chandragupta abdicated the throne in his old age and named his son as the next king.

- When Chandragupta appointed him as the next ruler, the faces of other people of “equal birth” bore a “melancholy look,” according to the Allahabad Pillar inscription.

- According to one interpretation, these other people were neighbouring kings, and Samudagupta’s ascension to the throne was uncontested.

- Another theory is that these other people were Gupta princes vying for the throne.

- Samudragupta’s background as the son of a Lichchhavi princess most likely helped him.

- Modern scholars debate the identity of a Gupta ruler named Kacha, whose coins describe him as “the exterminator of all kings.” These coins are very similar to those issued by Samudragupta.

- According to one theory, Kacha was an earlier name of Samudragupta: after extending his territory up to the ocean, the king took the regnal name Samudra (“Ocean”).

- Another theory holds that Kacha was a separate king (possibly a rival claimant to the throne) who reigned before or after Samudragupta.

Extent of his Empire

- Samudragupta’s dominion was enormous and was under his direct control. Nearly all of northern India was included.

- Gujarat, Orissa, Western Punjab, Western Rajputana Sindh, or Gujarat were not part of the Gupta kingdom.

- His empire therefore covered the most populous and productive nations in the Ganges Valley, extending from the Brahmaputra River in the east to the Yamuna and Chambal Rivers in the west, and on to the Narvada River in the south.

Military Career

- According to the Gupta inscriptions, Emperor Samudragupta had a distinguished military career. The Emperor Samudragupta’s inscription on the Eran stone claims that he subjugated “the whole tribe of monarchs” and that his opponents were afraid when they dreamed of him.

- Although the inscription omits the names of any of the conquered monarchs (perhaps because its main purpose was to document the placement of a Vishnu image in a temple), it seems Emperor Samudragupta had vanquished the majority of the kingdoms of this period.

- Emperor Samudragupta is credited with extensive conquests in the subsequent Allahabad Pillar inscription, which was penned by his minister and military officer Harishena. It provides the most thorough chronicle of Emperor Samudragupta’s military victories, detailing them in a mix of chronological and primarily geographical order.

- According to this, Emperor Samudragupta participated in a hundred wars, sustained a thousand wounds that resembled battle scars, and attained the title of Parakrami (Valourous).

- Emperor Samudragupta is referred to in the Mathura stone inscription of Emperor Chandragupta II as the “exterminator of all monarchs.”

Administration

- Samudragupta was a capable and successful administrator who set up a civil administration system that upheld peace and prosperity throughout the vast empire.

- Although the provinces enjoyed autonomy, the central government essentially controlled supervision.

- He altered the formal structure by placing the authorities under his control.

- This arrangement essentially persisted until the Musalmans finished capturing Northern India.

Conquests

- Samudragupta developed many plans for his conquests in the north and south.

- He made the decision to conquer the nearby Kingdoms before setting off on distant expeditions.

- Aryavarta was conquered in his first campaign. In the third phase, he then charged towards Dakshinapatha and marched on the second Aryavarta War.

- Samudragupta was also in charge of the invasion of the Atavika or Forest Kingdoms in addition to these significant invasions.

- He was also engaged in political discussions with far-off foreign powers while maintaining diplomatic ties with countries on the fringes of the Gupta empire.

- Digvijaya, which requires subduing the southern enemy monarchs, Grahana, which entails seizing control of the nations, and Anugraha, which entails allowing them to rule their kingdoms under his Suzerainty, are the three pillars of Samudragupta’s strategy.

Inscriptions

- Two inscriptions from the reign of Samudragupta have been discovered:

- Inscription on the Allahabad Pillar

- Inscription on the Eran stone

- The Allahabad Pillar inscription, according to Fleet, was issued posthumously during the reign of Chandragupta II, but modern scholars disagree.

- Two other records are attributed to Samudragupta’s reign, but their veracity is questioned:

- Gaya inscription, dated regnal year 9

- Nalanda inscription, dated regnal year 5

- Both of these inscriptions state that they were commissioned by Gupta officer Gopaswamin. These records, like Chandragupta II’s Mathura stone inscription, refer to Samudragupta as the “restorer of the Ashvamedha sacrifice.”

- It appears suspicious that this claim was made so early in Samudragupta’s reign, as it does not appear in the later Allahabad Pillar inscription.

- These records were issued during Samudragupta’s reign and were damaged after a while, so they were restored during Chandragupta II’s reign.

Allahabad Pillar

Eran Inscription

Art and Culture

- Samudragupta had a deep love for literature, art, and education.

- After penning several pieces of Sanskrit poetry, he was given the name Kaviraj.

- His grandeur and majesty were enhanced by the presence of many eminent scholars in his court.

- The Allahabad inscription’s author, Harisena, was well-known in his court.

- He had musical talent as well. He appears as a musician playing a Veena while sitting on a sofa on a number of his coins.

- His court poets hailed his sophisticated mind, gift for poetry, and musical talent. Additionally, Samudragupta was a philosopher.

- In order to merit the company of the wise men, he is reported to have wished to dive thoroughly into the tattva, or knowledge, of the Sastras.

- He also supported Buddhist novelist and philosopher Vasubandhu, under whose guidance he learned Buddhism’s core principles.

- Samudragupta was accepting of all other religions despite being a devout Hindu who adhered to the Brahmanical system.

- He authorised the construction of a Buddhist monastery at Bodh Gaya for monks of the religion by the king of Ceylon.

- Samudragupta’s wide range of gold coins not only exhibit the height of ancient technical mastery in the craft of coinage, but also the wealth of the empire.

Asvamedha Yajna

- As a symbol of his dominion and imperial might, Samudragupta performed an Asvamedha Yajna and received the title of Maharajadhiraja.

- To commemorate the occasion, he issued special gold coins.

- The term Asvamedha prakarama appeared on the reverse of the coin, which also included a picture of the horse used as a sacrifice on the front.

- It is clear from this that he performed the yajna to elevate the Brahmanas back to their rightful place as the social elite.

Coinage

- Following Samudragupta’s conquests in the northwest of the subcontinent, the Gupta Empire adopted the Kushan Empire’s coinage, adopting its weight standard, techniques, and designs.

- The Guptas even borrowed the name Dinara from the Kushans for their coinage, which ultimately came from the Roman name Denarius aureus.

- Samudragupta’s standard coin type is very similar to the coinage of later Kushan rulers, including the sacrificial scene over an altar and the depiction of a halo, while differences include the ruler’s headdress (a close-fitting cap instead of the Kushan pointed hat), the Garuda standard instead of the trident, and Samudragupta’s Indian jewellery.

Samudragupta’s standard coin type

Conclusion

Samudragupta is a remarkable character who ushers in a new era of unequaled material prosperity in the history of ancient India. The Gupta dynasty’s subsequent ruler, Chandragupta ll, succeeded Samudragupta.

Chandragupta II, also known as Vikramaditya, is regarded as one of the greatest rulers of the Gupta dynasty. Chandragupta II was the son of Samudragupta and Datta Devi. According to historical records, Chandragupta II was a strong, vigorous ruler who was well qualified to govern and expand the Gupta Empire. He ruled the Gupta Empire from 380 to 412 C.E., during the Golden Age of India. Based on coins and a supia pillar inscription, it is believed that Chandragupta II adopted the title ‘Vikramaditya.’

Coin of Chandragupta II

Features

- Chandragupta II (c. 380 – c. 412 CE), also known as Vikramaditya and Chandragupta Vikramaditya, was the third ruler of India’s Gupta Empire and one of the dynasty’s most powerful emperors.

- Chandragupta carried on his father’s expansionist policy, primarily through military conquest.

- He defeated the Western Kshatrapas and expanded the Gupta Empire from the Indus River in the west to the Bengal region in the east, and from the Himalayan foothills in the north to the Narmada River in the south, according to historical evidence.

- Prabhavatigupta, his daughter, was queen of the southern Vakataka kingdom, and he may have had influence in the Vakataka territory during her regency.

- During Chandragupta’s reign, the Gupta Empire reached its pinnacle. According to the Chinese pilgrim Faxian(Fa-Hien), who visited India during his reign, he ruled over a peaceful and prosperous kingdom.

- The legendary Vikramaditya is most likely based on Chandragupta II (among other kings), and the noted Sanskrit poet Kalidasa may have served as his court poet.

Names and Titles

- Chandragupta II was the dynasty’s second ruler to bear the name “Chandragupta,” following his grandfather Chandragupta I. As evidenced by his coins, he was also known simply as “Chandra.”

- According to his officer Amrakardava’s Sanchi inscription, he was also known as Deva-raja. His daughter Prabhavatigupta’s records, issued as a Vakataka queen, refer to him as Chandragupta as well as Deva-gupta.

- Another spelling of this name is Deva-shri. According to the inscription on the Delhi iron pillar, King Chandra was also known as “Dhava.”

- Chandragupta was given the titles Bhattaraka and Maharajadhiraja, as well as the moniker Apratiratha (“having no equal or antagonist”).

- The Supiya stone pillar inscription, which was commissioned during the reign of his descendant Skandagupta, also refers to him as “Vikramaditya.”

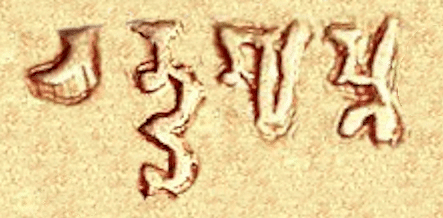

Name Chandragupta in Gupta Script

Background

- According to his own inscriptions, Chandragupta was the son of Samudragupta and queen Dattadevi.

- Chandragupta succeeded his father on the Gupta throne, according to the official Gupta genealogy. The Sanskrit play Devichandraguptam, along with other evidence, suggests that he had an elder brother named Ramagupta who ascended to the throne before him.

- When Ramagupta is besieged, he decides to surrender his queen Dhruvadevi to a Shaka enemy, but Chandragupta disguises himself as the queen and kills the enemy.

- Later, Chandragupta dethrones Ramagupta and ascends to the throne.

- Modern historians debate the historicity of this narrative, with some believing it is based on true historical events and others dismissing it as a work of fiction.

Military Career

- The Udayagiri inscription of Chandragupta’s foreign minister Virasena suggests that the king had a distinguished military career. It is stated that he “bought the earth,” paying for it with his prowess, and reduced the other kings to the status of slaves.

- His empire appears to have stretched from the mouth of the Indus and northern Pakistan in the west to the Bengal region in the east, and from the Himalayan terai region in the north to the Narmada River in the south.

- The Ashvamedha horse sacrifice was performed by Chandragupta’s father, Samudragupta, and his son, Kumaragupta I, to demonstrate their military prowess.

- The discovery of a stone image of a horse near Varanasi in the twentieth century, and the misreading of its inscription as “Chandramgu” (taken to be “Chandragupta”), led to speculation that Chandragupta also performed the Ashvamedha sacrifice. However, no actual evidence exists to support this theory.

Conquests

Western Kshatrapas

- According to historical and literary evidence, Chandragupta II had military victories against the Western Kshatrapas (also known as Shakas), who ruled in west-central India.

- The “Shaka-Murundas” are mentioned among the kings who tried to appease Chandragupta’s father Samudragupta in the Allahabad Pillar inscription.

- Samudragupta may have reduced the Shakas to a subordinate alliance, and Chandragupta completely subjugated them.

- The Western Kshatrapas was the only significant power to rule in this region during Chandragupta’s reign, as evidenced by their distinct coinage. The Western Kshatrapa rulers’ coinage abruptly came to an end in the last decade of the fourth century.

- This type of coin reappears in the second decade of the fifth century and is dated in the Gupta era, implying that Chandragupta subjugated the Western Kshatrapas.

Punjab

- Chandragupta appears to have marched through the Punjab region and up to the Vahlikas’ country, Balkh in modern-day Afghanistan.

- Some short Sanskrit inscriptions in Gupta script at the Sacred Rock of Hunza (in modern-day Pakistan) mention the name Chandra.

- Several of these inscriptions mention the name Harishena, and one mentions Chandra with the epithet “Vikramaditya.” Based on the identification of “Chandra” with Chandragupta and Harishena with Gupta courtier Harishena, these inscriptions can be regarded as additional evidence of a Gupta military campaign in the area.

- This identification, however, is not certain, and Chandra of the Hunza inscriptions could have been a local ruler.

- The phrase “seven faces” mentioned in the iron pillar inscription refers to Indus’ seven mouths. The term is thought to refer to the Indus tributaries: the five rivers of Punjab (Jhelum, Ravi, Sutlej, Beas, and Chenab), as well as the Kabul and Kunar rivers.

- It is quite possible that Chandragupta passed through the Punjab region during this campaign: the use of the Gupta era in an inscription found at Shorkot, as well as some coins bearing the name “Chandragupta,” attest to his political influence in this region.

Bengal

- The identification of Chandra with Chandragupta II also implies that Chandragupta won victories in the Vanga region of modern-day Bengal.

- According to his father Samudragupta’s Allahabad Pillar inscription, the Samatata kingdom of the Bengal region was a Gupta tributary.

- The Guptas are known to have ruled Bengal in the early sixth century CE, but there are no records of their presence in this region during the intervening period.

- It is possible that Chandragupta annexed a large portion of the Bengal region to the Gupta empire, and that this control lasted into the sixth century.

- According to the inscription on the Delhi iron pillar, an alliance of semi-independent Bengal chiefs unsuccessfully resisted Chandragupta’s attempts to extend Gupta influence in this region.

Matrimonial Alliance

- According to Gupta records, Dhruvadevi was Chandragupta’s queen and the mother of his successor Kumaragupta I. Dhruva-svamini is mentioned on the Basarh clay seal as a Chandragupta queen and the mother of Govindagupta.

- It appears that Dhruvasvamini was most likely another name for Dhruvadevi, and that Govindagupta was Kumaragupta’s uterine brother.

- Chandragupta also married Kuvera-naga (alias Kuberanaga), whose name indicates that she was a princess of the Naga dynasty, which held considerable power in central India before Samudragupta subjugated them.

- This matrimonial alliance may have aided Chandragupta in consolidating the Gupta empire, and the Nagas may have aided him in his war against the Western Kshatrapas.

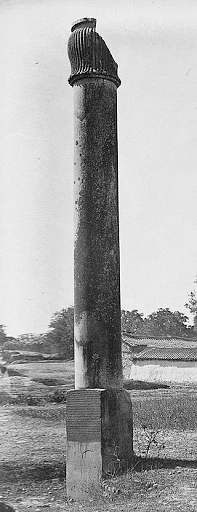

Mehrauli Iron Pillar

- Close to the Qutub Minar stands one of Delhi’s most unusual structures, an iron pillar with an inscription declaring that the pillar was created by artisans in the fourth century C.E. in honour of Hindu God Vishnu and in memory of Chandragupta II.

- The Mehrauli Iron Pillar was originally located on a hill near Beas, and it was brought to Delhi by Radhakumud Mookerji, a king of the Gupta Empire. This pillar attributes the following to Chandragupta II (Vikramaditya):

- Conquest of the Vanga countries when he fought alone against an enemy alliance.

- Valakas was defeated in a battle that spanned Sindhu’s seven mouths.

- Spread Chandragupta II’s fame to the southern seas.

- He attained Ekadhirajjyam through the prowess of his arms .

- He named the Mehrauli Iron Pillar Vishnupasa in honour of the Hindu God Vishnu.

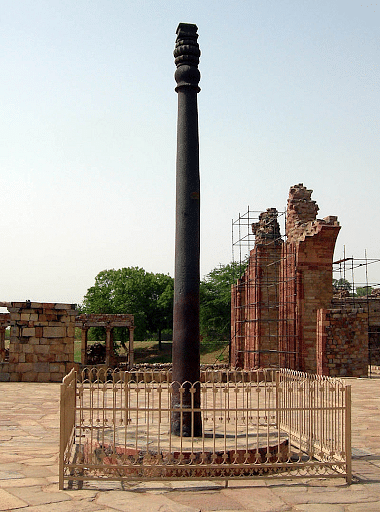

Iron Pillar in Delhi

Sanchi Inscription

- The Chandragupta II Sanchi inscription is an epigraphic record that documents a donation to the Buddhist establishment at Sanchi during the reign of King Chandragupta II.

- It is from the Gupta era and dates from the year 93.

- Sanchi is located in Madhya Pradesh’s Raisen District.

- The inscription is located on the railing of the main stupa, immediately to the left of the eastern gate.

Inscription of Chandragupta II at Sanchi

Administration

Several feudatories of Chandragupta are known from historical records:

- Maharaja Sanakanika, a feudatory whose construction of a Vaishnava temple is recorded in the Udayagiri inscription.

- Maharaja Trikamala, a feudatory known from a Gaya inscription engraved on a Bodhisattva image.

- Maharaja Shri Vishvamitra Svami, a feudaotry known from a seal discovered in Vidisha.

- Maharaja Svamidasa, the ruler of Valkha, was also most likely a Gupta feudatory; is dated in the Kalachuri calendar era.

Various historical records identify the following Chandragupta ministers and officers:

- Vira-Sena, Foreign minister is known from the Udayagiri inscription, which records his construction of a Shiva temple.

- Amrakardava, a military officer, is remembered in the Sanchi inscription for his contributions to the local Buddhist monastery.

- Shikhara-svami was a minister who wrote the political treatise Kamandakiya Niti.

Navratnas

Chandragupta II was known for his deep interest in art and culture, and his court was adorned with nine gems known as Navratna. The diverse fields of these 9 gems demonstrate Chandragupta’s patronage of the arts and literature. The following is a brief description of the nine Ratnas:

- Amarsimha: Amarsimha was a Sanskrit poet and lexicographer, and his Amarkosha is a vocabulary of Sanskrit roots, homonyms, and synonyms. It is also known as Trikanda because it is divided into three sections: Kanda 1, Kanda 2, and Kanda 3. It contains ten thousand words.

- Dhanvantri: Dhanvantri was an excellent physician.

- Harisena: Harisena is credited with writing the Prayag Prasasti, or Allahabad Pillar Inscription. The title of Kavya’s inscription, but it contains both prose and verse. The entire poem is in one sentence, including the first eight stanzas of poetry, a long sentence, and a concluding stanza. In his old age, Harisena was in the court of Chandragupta and describes him as Noble, asking him, “You Protect all this earth.”

- Kalidasa: Kalidasa is India’s immortal poet and playwright, and a peerless genius whose works have become famous throughout the world in the modern era. The translation of Kalidasa’s works into numerous Indian and foreign languages has spread his fame throughout the world, and he now ranks among the top poets of all time. Rabindranath Tagore not only popularised Kalidasa’s works but also elaborated on their meanings and philosophy, making him an immortal poet and dramatist.

- Kahapanaka: Kahapanka was an astrologer. There aren’t many details available about him.

- Sanku: Sanku worked in architecture.

- Varahamihira: Varahamihira (d. 587) was a Ujjain resident who wrote three important books: Panchasiddhantika, Brihat Samhita, and Brihat Jataka. The Surya Siddhanta is included in the Panchasiddhantaka, which is a summary of five early astronomical systems. Another system he describes, the Paitamaha Siddhanta, appears to share many similarities with Lagadha’s ancient Vedanga Jyotisha. Brihat Samhita is a collection of topics that provide interesting details about the beliefs of the time. Brihat Jataka is an astrology book that appears to be heavily influenced by Greek astrology.

- Vararuchi: Vararuchi is the name of another gem of Chandragupta Vikramaditya, a grammarian and Sanskrit scholar. Some historians have linked him to Katyayana. Vararuchi is credited with writing the first Grammar of the Prakrit language, Prakrit Prakasha.

- Vetalbhatta: Vetalbhatta was a magician.

Religion

- Many of Chandragupta’s gold and silver coins, as well as the inscriptions issued by him and his successors, describe him as a parama-bhagvata, or devotee of the god Vishnu.

- One of his gold coins, discovered at Bayana, refers to him as chakra-vikramah, which translates as “[one who is] powerful [due to his possession of the] discus,” and depicts him receiving a discus from Vishnu.

- In the year 82 of the Gupta era, Chandragupta’s feudatory Maharaja Sanakanika built a Vaishnava cave temple, according to an Udayagiri inscription.

- Chandragupta was also accepting of other religions. The Udayagiri inscription of Chandragupta’s foreign minister Virasena records the construction of a temple dedicated to the god Shambhu (Shiva).

- In the year 93 of the Gupta era(c. 412-413 CE), his military officer Amrakardava made donations to the local Buddhist monastery, according to an inscription discovered near Udayagiri.

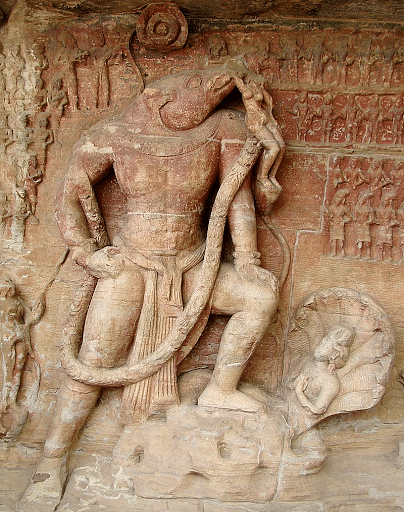

Development of Vaishnavism in India, and the establishment of the Udayagiri Caves with Vaishnava iconography

Coinage

- Most of the gold coin types introduced by his father Samudragupta were continued by Chandragupta, including the Sceptre type, the Archer type, and the Tiger-Slayer type.

- However, Chandragupta II also introduced several new types, including the Horseman and Lion-slayer types, which were used by his son Kumaragupta I.

- Chandragupta’s gold coins depict his martial spirit as well as his peacetime pursuits.

Gold coin of Chandragupta II

Fa-Hien’s Visit

- Pataliputra was largely ignored by warrior kings such as Samudragupta and Vikramaditya, but it remained a magnificent and populous city throughout Chandragupta II’s reign.

- Patliputra was later reduced to reigns following the Hun invasions in the sixth century. Shershah Suri, on the other hand, rebuilt and revitalized Pataliputra as today’s Patna.

- Fa Hien’s accounts provide a contemporary account of Chandragupta Vikramaditya’s administration. Fa Hien (337 – ca. 422 AD) was so engrossed in his search for Buddhist books, legends, and miracles that he couldn’t recall the name of the mighty monarch under whose rule he had lived for 6 years.

- He saw and was impressed by Asoka’s palace at Pataliputra, so it is certain that Asoka’s palace existed even during the Gupta era. He also mentions a stupa and two monasteries nearby, both of which are attributed to Asoka.

- He mentioned 600-700 monks living there and receiving lectures from teachers from all over. He mentions that the towns of Magadha were the largest in the area of the Gangetic Plains, which he refers to as central India.

- Fa Hien goes on to say that the people of the western part (Malwa) were content and unconcerned. He mentions that they are not required to register their household or appear before a magistrate. People did not lock their doors. The passports, and those who wanted to stay or go, did not bind them.

- Fa Hien goes on to say that no one kills living things, drinks wine, or eats onion or garlic. There are no pigs or fowls, no cattle trading, and no butchers. All of this was done by Chandals alone.

- Fa Hien studied Sanskrit without interruption for three years at Pataliputra and two years at the Port of Tamralipti. The roads were clear and safe for the passengers to travel on.

- The accounts of Fa Hien show that India was probably never better governed than during the reign of Chandragupta Vikramaditya.

- The account of Fa-Hien and his unobstructed itinerary all around gives details about the Golden Era of Mother India, attesting to the prosperity of the Indians and the tranquillity of the empire.

Conclusion

Chandragupta II, a powerful and energetic ruler, was well-suited to rule over a vast empire. Kumaragupta I, also known as Mahedraditya, succeeded Chandragupta II. His reign lasted 40 years and was assigned to him during the years 415-455 AD. He was a capable ruler, and there is no doubt that his empire grew rather than shrank.

Kumaragupta I was the son of Gupta emperor Chandragupta II and queen Dhruvadevi. From 413 to 455 AD, he was in power. He was also known as Shakraditya and Mahendraditya. He established Nalanda University. He went by the name Shakraditya as well. Hunas encroached on India during his rule.

Coin of Kumaragupta I

Features

- Kumaragupta I (r. c. 413–455 CE) was an emperor of Ancient India’s Gupta Empire. He appears to have maintained control of his inherited territory, which extended from Gujarat in the west to the Bengal region in the east, as the son of Gupta emperor Chandragupta II and queen Dhruvadevi.

- Although no concrete information about Kumaragupta’s military achievements is available, he performed an Ashvamedha sacrifice, which was typically performed to demonstrate imperial sovereignty.

- Some modern historians believe he subdued the Aulikaras of central India and the Traikutakas of western India based on epigraphic and numismatic evidence.

- The Bhitari pillar inscription states that his successor Skandagupta restored the Gupta family’s fallen fortunes, which has led to speculation that during his final years, Kumaragupta suffered reverses, possibly against the Pushyamitras or the Hunas.

- However, this cannot be said with certainty, and the situation described in the Bhitari inscription could have resulted from events that occurred after his death.

Background

- Kumaragupta was the son of Gupta emperor Chandragupta II and Dhruvadevi.

- The most recent inscription of Chandragupta is dated around 412 CE, while Kumaragupta’s earliest inscription is dated around 415 CE (year 96 of the Gupta era). As a result, Kumaragupta must have ascended to the throne in or around 415 CE.

- Kumaragupta was known as Maharajadhiraja, Parama-bhattaraka, and Paramadvaita.

- He also adopted the title Mahendraditya, and several variants of this name appear on his coins, including Shri-Mahendra, Mahendra-simha, and Ashvamedha-Mahendra.

- Kumaragupta’s title may have been Shakraditya, the name of a king mentioned in Buddhist texts.

During his Reign

- Kumaragupta inherited a vast empire built on the conquests of his father, Chandragupta II, and grandfather, Samudragupta. There is no concrete information about his military accomplishments.

- Inscriptions issued during his reign have been discovered in Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, West Bengal, and Bangladesh; an inscription of his son has been discovered in Gujarat.

- Furthermore, his garuda-inscribed coins have been discovered in western India, and his peacock-inscribed coins have been discovered in the Ganges valley.

- This implies that he was able to keep control of the vast territory he inherited.

- Even if his reign was uneventful militarily, he must have been a strong ruler to be able to maintain a stable government in a large empire, as evidenced by epigraphic and numismatic evidence.

- There are some indications that Kumaragupta’s reign was not without wars and upheaval. He worshipped the war god Karttikeya, for example, and his gold coins indicate that he performed the Ashvamedha ceremony, which was used by ancient kings to demonstrate their sovereignty.

- However, because no concrete information about any military conquests by him is available, it is unclear whether this performance is indicative of any conquests.

Possible Conquests

South-Western Conquests

- Kumaragupta’s coins were discovered in modern-day Maharashtra, which was to the south-west of the core Gupta territory. 13 coins from Achalpur and a hoard of 1395 silver coins from Samand in Satara district are among them.

- His coins, discovered in south Gujarat, are similar to those issued by the Traikutaka dynasty, which ruled this region.

- This has led to speculation that Kumaragupta was victorious over the Traikutakas.

Annexation of Dashapura

- The Mandsaur inscription from 423 CE mentions a line of kings whose names end in -varman and who most likely had their capital at Dashapura (modern Mandsaur).

- The inscription refers to one of these kings, Nara-varman, as a “Aulikara,” which appears to be the name of the dynasty.

- The inscription describes a guild of silk weavers who migrated to Dashapura from the Lata region of modern-day Gujarat.

- It then abruptly departs from this topic and mentions “while Kumaragupta ruled the entire earth.”

- It goes on to say that a sun temple was built around 436 CE during the reign of Nara-grandson varman’s Bandhu-varman, but it was later destroyed or damaged by other kings, and the guild had it repaired around 473 CE.

Administration

- According to epigraphic evidence, Kumaragupta ruled his empire through governors known as Maharajas (“great kings”), who administered various provinces (Bhuktis).

- The provinces’ districts (vaishyas) were governed by district magistrates (Vishyapatis), who were assisted by a council of advisors.

- He is most likely the same Ghatotkacha-Gupta mentioned in a seal discovered at Vaishali and known to have issued a gold coin.

- Following Kumaragupta’s death, he may have declared independence for a brief period of time.

- It’s impossible to say whether Kumaragupta was troubled in his later years.

- For example, it’s possible that the drafter of the Man Kuwar inscription made an error due to carelessness or ignorance.

- As a result, the problems mentioned in the Bhitari inscription could have occurred after Kumaragupta’s death: these issues were most likely caused by a disputed succession to the throne, which resulted in a civil war.

- However, this is only a guess, and according to another theory, the situation described in the Bhitari inscription could have been the result of a Huna invasion.

Religion

- Various faiths, including Shaivism, Vaishnavism, Buddhism, and Jainism, flourished during Kumaragupta’s reign, according to epigraphic evidence.

- Kumaragupta’s silver coins depict him as a devotee of the god Vishnu (parama-bhagavata or bhagavata). His gold, silver, and copper coins depict Vishnu’s vahana Garuda.

- He was also a devotee of the war god Karttikeya (also known as Skanda): his coins depict Karttikeya seated on a peacock.

- He named his son Skandagupta after the god, and his own name “Kumara” appears to be based on another name of the god.

- According to Buddhist writers Xuanzang (7th century) and Prajnavarman (8th century), the Buddhist mahavihara at Nalanda was founded by a king named Shakraditya.

- After Shakraditya, Xuanzang mentions Budhagupta (a successor of the later king Kumaragupta II): “the monastery was enriched by the endowments of the kings Shakraditya, Budhagupta, Tathagatagupta, and Baladitya.” This calls into question Shakraditya’s identification with Kumaragupta I.

Standing Buddha

Coinage

- Kumaragupta issued the most coins of any Gupta king. Kumaragupta-I, also known as “Mahendraditya” on coinage, minted 14 different types of gold (Dinar) and silver (Denaree) coins. His coinage alone speaks volumes about the scope and prosperity of his reign. His long reign saw both the apex and the fall of the kingdom, as Hun invasions disrupted the Gupta Empire later in his reign.

- The Archer type: It depicts the King standing to the left, holding an arrow in his right hand and a bow in his left.

- Swordsman Type: The King is depicted holding a sword in his left hand and reciting the Bramhi legend “Gama – vajitya – sucharitaihi – kumaragupta – Divam – jayati.”

- The Asvamedha Type: It was created to commemorate the Horse Sacrifice. The obverse legend reads “Jayati Divam Kumarah,” while the reverse legend reads “Sri Asvamedha Mahendra.”

- Horsemen Type : King on a horse with legends adorning his strength and victories on the obverse and the “Ajitamahendraha” legend on the reverse.

- Lion Slayer: It depicts the king slaying a lion and has the legend “shri mahendra simha” or “simhamahendrarah” on the reverse.

- Tiger Slayer: Like the lion slayer, this coin depicts the king slaying the tiger on the obverse, with the legend “‘Sriman vyaghra balaparakramah” on the reverse.

- Peacock or Kartikeya type: One of his most beautiful coins depicts the King with his right hand holding a cluster of grapes for a Peacock.

- The Pratapa Type: This is a very rare type that depicts the king with two servants on both sides bearing the Garuda Standard. On the reverse, the legend “Shri Pratapah” appears.

- Elephant Rider Type: Despite the unclear markings, this variant is attributed to Kumaragupta I due to similarities in coin design and manufacture. The coin depicts the King riding an elephant with an attendant.

Silver Coin of Kumaragupta I

Elephant Rider Coin

Horseman type coin

Inscriptions

- There are at least 18 inscriptions from Kumaragupta’s reign. All of these inscriptions were issued by private individuals rather than Gupta royals, and the majority of them are religious in nature.

- Nonetheless, they contain important historical information, such as a genealogy of the Gupta kings, dates, locations of places in the Gupta empire, and the names of royal officers.

- During Kumaragupta’s reign, the earliest extant Gupta inscriptions from the Bengal region were issued.

Kumaragupta’s Tumain inscription, discovered in Madhya Pradesh

Conclusion

According to one theory, Kumaragupta’s sons, Skandagupta and Purugupta, were involved in a succession dispute. Another possibility is that Purugupta, the chief queen’s son, was a minor when Kumaragupta I died, allowing Skandagupta, the son of a junior queen, to ascend the throne. Skandagupta succeeded Kumaragupta, and his descendants became the next kings.

Skandagupta (r. 455–467) was an Indian Gupta Emperor. According to the inscription on his Bhitari pillar, he restored Gupta supremacy across the subcontinent by defeating his enemies, who could have been rebels or foreign invaders. He repelled an invasion by the Indo-Hephthalites (known as Hunas in India), who were most likely the Kidarites. He appears to have kept control of his inherited territory and is widely regarded as the last of the great Gupta Emperors. The Gupta genealogy after him is unclear, but he was most likely succeeded by Purugupta, his younger half-brother.

Features

- Skandagupta was a Gupta Emperor from northern India. Skandagupta was the son of Gupta emperor Kumaragupta I.

- He ascended to the throne in 455 AD and reigned until 467 AD.

- Skandagupta demonstrated his ability to rule by defeating Pushyamitras during his early years in power, earning the title of Vikramaditya.

- During his 12 year reign, he not only defended India’s great culture, but also defeated the Huns, who had invaded India from the north west.

- He is widely regarded as the final of the great Gupta Emperors.

Background

- Skandagupta was the son of Kumaragupta I, the Gupta emperor. His mother could have been a junior queen of Kumaragupta’s concubine.

- This theory is based on the fact that Skandagputa’s inscriptions mention his father’s name but not his mother’s.

- Skandagupta’s Bhitari pillar inscription, for example, names the chief queens (mahadevis) of his ancestors Chandragupta I, Samudragupta, and Chandragupta II but not his father Kumaragupta.

- Some scholars believe that Devaki was his mother’s name based on the inscription.

Ascension to the Throne

- Skandagupta ascended to the throne in the year 136 of the Gupta era. According to the Bhitari pillar inscription, he restored “his family’s fallen fortunes.”

- He prepared for this, according to the inscription, by sleeping on the ground for a night and then defeating his enemies, who had grown wealthy and powerful.

- After defeating his opponents, he went to see his widowed mother, who was crying “tears of joy.”

- His mother was most likely Kumaragupta’s junior wife, not the chief queen, and thus his claim to the throne was illegitimate.

- According to the Junagadh inscription, the goddess of fortune, Lakshmi, chose Skandagupta as her husband after rejecting all other “sons of kings.”

- Skandagupta’s coins depict a woman presenting him with an unidentified object, most likely a garland or ring.

- Following Kumaragupta’s death, it is said that several people in the Gupta empire assumed sovereign status. Kumaragupta’s brother, Govindagupta, is among them.

Conflict with the Huns

- The Indo-Hephthalites (also known as the White Huns or Hunas) invaded India from the northwest during Skandagupta’s reign, advancing as far as the Indus River.

- Skandagupta defeated the Huns, according to the inscription on the Bhitari pillar.

- The date of the Hun invasion is unknown. It is mentioned in the Bhitari inscription after describing the conflict with the Pushyamitras (or the Yudhyamitras), implying that it occurred later during Skandagupta’s reign.

- However, a possible reference to this conflict in the Junagadh inscription suggests that it occurred at the start of Skandagupta’s reign or during his father Kumaragupta’s reign.

- The Junagadh inscription, dated to the Gupta era’s year 138 (c. 457- 458 CE), mentions Skandagupta’s victory over the mlechchhas (foreigners).

- The victory over the mlechchhas occurred in or around the year 136 of the Gupta era (c. 455 – 456 CE), when Skandagupta ascended to the throne and appointed Parnadatta as governor of the Saurashtra region, which included Junagadh.

- Because Skandagupta is not known to have fought any other foreigners, these mlechchhas were most likely Hunas.

- If this identification is correct, it is possible that Skandagupta was sent as a prince to check the Huna invasion at the border, and Kumaragupta died in the capital while this conflict was going on; Skandagupta returned to the capital and defeated rebels or rival claimants to ascend the throne.

Bhitari Pillar Inscription of Skandagupta

- Skandagupta’s Bhitari pillar inscription was discovered in Bhitari, Saidpur, Ghazipur, Uttar Pradesh, during the reign of Gupta Empire ruler Skandagupta (c. 455 – c. 467 CE).

- The inscription is extremely important in understanding the chronology of the various Gupta rulers, among other things. It also mentions Skandagupta’s conflict with the Pushyamitras and the Hunas.

- The inscription is written in 19 lines, beginning with a genealogy of Skandagupta’s ancestors, followed by a presentation of Skandagupta himself, and finally a presentation of his achievements.

Bhitari Pillar and Inscription

Western India

- The inscription on the Junagadh rock, which contains inscriptions of earlier emperors Ashoka and Rudradaman, was engraved on the orders of Skandagupta’s governor Parnadatta.

- According to the inscription, Skandagupta appointed governors for all provinces, including Parnadatta as governor of Surashtra.

- It is unclear whether the verse refers to routine appointments made by the king or his actions following a political upheaval caused by a war of succession or invasion.

- The inscription lists several qualifications for the governorship of Surashtra, stating that only Parnadatta possessed these qualifications.

- Again, it’s unclear whether these were actual qualifications for being a governor under Skandagupta’s rule, or if the verse is simply meant to praise Parnadatta.

- Parnadatta appointed his son Chakrapalita as magistrate of Girinagara (near modern Junagadh-Girnar), presumably the capital of Surashtra.

Coinage

- Samudragupta issued fewer gold coins than his predecessors, and some of these coins contain a smaller amount of gold. It is possible that the various wars he fought strained the state treasury, but this cannot be proven.

- Skandagupta issued five different types of gold coins: Archer, King and Queen, Chhatra, Lion-slayer, and Horseman type. His silver coins come in four varieties: Garuda, Bull, Altar, and Madhyadesha type.

- The initial gold coinage was based on his father Kumaragupta’s old weight standard of approximately 8.4 gm. This initial coinage is extremely rare.

- Skandagupta revalued his currency at some point during his reign, switching from the old dinar standard to a new suvarna standard weighing approximately 9.2 gm.

- These later coins were all of the Archer type, and all subsequent Gupta rulers followed this standard and type.

Skandagupta coin in Western Satraps style

Skandagupta’s coin facing Garuda

Conclusion

Skandagupta’s last known date is 467-468 CE (year 148 of the Gupta era), but he most likely ruled for a few more years. Skandagupta was most likely succeeded by Purugupta, who appears to be his half-brother. Purugupta was Kumaragupta I’s son from his chief queen and thus his legitimate successor. It is possible that he was a minor at the time of Kumaragupta I’s death, which allowed Skandagupta to ascend the throne. Skandagupta appears to have died heirless, or his son may have been dethroned by Purugupta’s family.

For nearly 250 years the Gupta empire provided political unity, good administration and economic and cultural progress to North India. The period, therefore, has been rightly regarded as the most glorious epoch in Indian history. But then it disappeared from the scene.

The difficulties of the empire began during the later period of the reign of Kumar Gupta I. Skanda Gupta faced them successfully but could not finish them. The difficulties were converted into weaknesses after him when his weak successors failed to rise to the occasion. This led to the disruption and finally to the extinction of the empire. The Gupta empire also met the fate of the Maurya empire and the causes too, more or less, were similar.

Skanda Gupta successfully checked the invasion of the Hunas as a crown- prince and as an emperor he inflicted a crushing defeat on them. He also succeeded in eliminating completely the threat posed by Pushyamitras to the empire from the South. Yet these campaigns heavily taxed the financial and military resources of the empire. Therefore, he was forced to lower the quality of his gold coins.