Ancient History – 1st Year

Paper – I (Short Notes)

Unit I

Language/भाषा

Introduction

Archaeology is a science by which the remains of ancient man can be methodically and systematically studied to obtain a complete picture of his ancient culture society to a possible extent. I t is a study of human behaviour and cultural changes happened in the past through material remains, the term “Archaeogy” is derived from the two Greek words:

1) “archaeos” or “arche” means ancient or beginning and 2) “logos” means science or theory. Archaeology is essentially a method of reconstructing the past from the surviving traces of former societies.

It was briefly shown earlier how archaeology is increasingly becoming a multi-disciplinary enquiry and how it depends on many natural and social sciences like geology, anthropology, physics, chemistry, botany, history, etc. As has been rightly observed, “archaeological enquiry has become so diversified no one can even pretend to be fully conversant with all branches.

The main focus of archaeology is the study of human past that deepens our understanding of the world in a more meaningful and resourceful manner. The study of human past means the study of human behavioural and cognitive systems within a given socio-politico-cultural context. The human behavioural activities could be discerned through material evidences whereas the cognitive systems could be realised by understanding the cultural values that stand behind the material. To get a coherent picture of human behavioural and cognitive systems, archaeology has developed certain methodological approaches in collaboration with various specialized scientific fields. The specialized scientific fields such as physical, chemical, biological, anthropological, mathematical, geological, computer sciences, remote sensing and many more such allied scientific fields, in addition to the humanities and social sciences such as history, art, architecture, language, linguistic and religious studies are increasingly playing a greater role to decipher the human foot-prints in a more reliable manner. The intellectual tie-ups with scientific disciplines have facilitated in solving several research problems. All traditional and scientific approaches basically depend upon the nature of material evidences that are being unearthed by the archaeologists through well planned explorations and excavations.

Collections and Interpretations

The collection and interpretation of material remains are so important in archaeological studies. These are conditioned by two important means, yet interrelated areas, namely methods and theories. The way archaeological research is being conducted or the way the material remains are being collected and studied could be interpreted as method. Thus, the means of collection of maximum retrievable information are known as archaeological method. Theory means an idea or a set of ideas intended to explain facts or events. In archaeological context, the way the collected material remains are being interpreted to explain a particular event or series of events of the past can be called as archaeological theory. A method or theory followed in a particular context may become irrelevant in another context. Therefore, archaeologists design their research method to suit the needs of the problem of study. Both the archaeological method and theory play a dominant role in our understanding of the human past. There are several methods of collections of data since the nature of material evidences that are embedded in the soil in varied ecological zones differs. In the same way, the interpretations of the archaeological material also vary depending upon the nature of theoretical approach. Thus, the reconstruction of the past basically stands on these two workable platforms of intensive academic field of inquiry viz., theory and method.

The study of material remains of the ancient culture and civilization reminds us cultural continuity. The cultural continuity, discontinuity, integration and transformation are part of cultural process that are conditioned by various factors. The long-felt field experience advocates that domain knowledge plays a dominant role in understanding a particular culture. In the backdrop of field experience, archaeologists must take utmost care in the application of theories and methods in the interpretation. Archaeologists must be flexible, open-minded and receptive in their approach. Due to ever-growing field of science and technology, the study of archaeology has become more complex and responsive. Several established methods and theories are being constantly questioned and revised due to advances in science and technology. The progress made in science and technology sometime forces us to refashion our approach towards archaeology. As one experiences today, the development of science and technology in the past also must have played a greater role in changing the activities of the ancient society at large. For instance, the introduction of iron or development of water management system or navigational techniques must have changed the society at large. The researchers in the field of archaeology should approach each problem with open-mind and they must prepare to accept the outcome of the result that may even go against their wishes. The archaeologists must have a physical strength and mental ability to withstand the biological strain in the field and intellectual stress in the analysis at the laboratory. Thus, the duty of archaeologists is to discover, document, decode, describe, discuss, determine, disseminate and declare the results of findings for the advancement of knowledge on ancient society, to full-fill the aspiration of the contemporary society and to provide a good guidance to the future generation.

Definition and Scope

The term archaeology is derived from the Greek word. In Greek, archaeos means ancient and logos means discussion, reason or science. Thus, archaeology is a science involving the study of human past through material remains. It methodically and meticulously studies to obtain a complete picture of human behavioural and cognitive systems. In short, archaeology is the study of human behavioural and cognitive systems to understand the cultural changes or processes that happened in the past through material remains.

To understand the cultural process, archaeologists study all physical traces encountered both in excavations and explorations as movable and immovable objects and also tangible and intangible evidences. Among the physical remains, artefacts (portable human -made objects) occupy a primary position. Archaeologists try to discern the non-material life of the people through these movable and immovable objects. Archaeologists follow certain specific methods and a body of theories to get a comprehensive picture of the material and non-material life of the people.

In method, the focus is on the collection of data. In theory, the focus is on the interpretation or giving a better explanation on the collected material. In the past, archaeologists generally intended to give descriptive data to a site, but today, they apply theoretical systems for better interpretation of the data. In this attempt, they create certain conceptual basis to understand the human past. The human past has both a prehistoric (the period of human history before the advent of writing) and a historic antiquity (the period of human history after the advent of writing, preciously speaking after the decipherment of particular writing system). These historical moorings have gone through a slow process of biological evolution and cultural development. Human has lived on the earth in a particular social, physical and environmental context as one of the biological products. These contexts are dynamic and not static. In this dynamic process, the human use to live and leave their imprints in the form of material remains. These remains are generally observed in stratified deposits, which we call it as cultural remains or culture. This culture is subject to change brought out by human in their adaptation to environment. These inherent changes are reflected in assemblages of artefacts. These assemblages are recorded and studied to show how this culture has been transmitted and adopted by others. Edward Tylor, an anthropologist, defined culture as ‘knowledge, belief, art, morals, law, custom and any other capabilities and habits acquired by a man as member of the society” (Tylor 1871). These cultural pointers are stayed back as cultural deposits on a landscape.

Therefore, the whole landscape comprising several archaeological sites is a document and each archaeological site is a part of that document. Human interacted, both culturally and spiritually, with the landscape that are reflected in the form of settlements, architectural features, worshiping places, ritual spaces, burial monuments or in any human-made features. In certain cases, they collectively create a landscape such as sacred landscape. On certain occasions, the natural landscapes like mountains, caves, rivers and seas are considered as sacred landscape that are culturally associated in a more powerful manner. Beyond material evidences, certain natural substances are venerated as God in a particular belief system and these are culturally very explosive both in the past as well as in the present. Therefore, archaeologists must study the entire landscape with a specific goal to get an appreciable data for better interpretation and understanding.

Goals of Archaeology

Traditionally, archaeology has been equated with the discovery, recovery, inquiry, scrutiny, analysis and interpretation of the material remains of the human past. Now, goals of archaeology have been modified in an effort to learn more about relations between material culture and human behaviour. These goals stress the need to establish temporal and spatial controls on the materials under study. To achieve this, archaeologists have three principal goals (Sharer and Ashmore 1993:35).

These goals are:

- To consider the form of archaeological evidence and its distribution in time and space.

- To determine the functionof archaeological evidence and thereby construct models of ancient behaviour.

- To delimit the process of culture and determine how and why cultures change.

The first goal (form) is the description and classification of the material evidence to develop models of artefact assemblage distribution through time and space. The study of artefact assemblages helps to reconstruct the historical development of cultural changes by building local and regional sequences. For instance, Heinrich Dressel’s classification of Roman amphorae could be cited as finest example (Dressel 1899). In India, the approximate date and cultural association of the sites are being recognized generally based on the ceramic sequences. Such artefact assemblages such as ceramics (like pre-Harappan, Harappan, Northern-Black-Polished ware (NBP), Painted Grey ware (PGW), rouletted ware and black-and-red ware (BRW)), stone tools (like core tools of Madras hand axes, pebble tools of Soan valley, flake tools and celts ) and metal objects (copper hoards and Iron Age tools) were created in Indian context.

The second goal (function) focuses on the usage of various artefacts. This is done based on the study of forms. It assists to understand the ancient human behaviour in a given environment. The combined study of forms and functions helps us to reconstruct the past environment through the study of ethnoarchaeological, palaeobotonical, archaeozoological,

paleontological samples and many other subsistence patterns. For instance, the hand axes and cleavers encountered in Lower Palaeolithic culture and axes and adzes encountered in Neolithic culture reflect their function, subsistence pattern and also the past environment. The Lower Palaeolithic tools reflect the mode of subsistence pattern of the hunter-gatherer community that lived during Pleistocene period and the Neolithic tools echo the food producing society lived during Holocene period. The size and shape (i.e., form) of the tools determine their function which eventually determines the nature of subsistence patterns.

The third goal (process-the cultural process) is an attempt to understand the cultural change or process of change in a sequential or chronological order based on the study of tangible and intangible evidences. The study of cultural process is one of the major goals of new archaeology.

Cultural changes occur due to variety of reasons. The development of science and technology, spirituality, under exploitation or over exploitation of natural resources, change in environment, changes in social, political and economic structures, internal and external influences and many other such forces or pointers individually or collectively influence the cultural process. For instance, the introduction of metal technology like copper and iron, sea level fluctuations, river migrations, state formation or collapse, maritime contacts and identification of monsoon winds could be cited as some of the factors for the change in culture.

The various dynamics of cultural process cannot be understood without the involvement of various disciplines like history, anthropology, geology, biology, zoology, physics, chemistry, botany and many other interrelated sister disciplines. Thus, the inter-disciplinary studies play a vital role in archaeological interpretations. Understanding the crucial relationship that exists between archaeology and other disciplines is important to strengthen the study of human past and also to overcome certain deficiencies or discrepancies that erupt in the course of our interpretation.

Archaeology and other disciplines

Archaeology and History

Archaeology and History seeks about the human past through the material remains and written documents respectively. History brings out the textual documents the stone, papyrus, pottery and seal and it tries to rebuild the human past.

Archaeology and Anthropology

Archaeology is a sub discipline of Anthropology. Anthropology is sub divided into physical anthropology, cultural anthropology and archaeology. The skeletal remains recovered from excavations are studied by the physical anthropologists to determine the race, age, sex, behavioural pattern, dietary pattern, palaeo-demography, and other related aspects. the behavioural aspects that influence the human behaviour are studied in cultural anthropology. The non- material aspects like belief, faith, ritual, administrative mechanism, social pattern, language, movement and spread of language, etc., are discerned by applying anthropological theories.

Archaeology and Geology

The study of the development of the earth especially as preserved in its crust formations is called Geology. Its first contribution to archaeology is the principles of stratigraphy. It helps to determine the relative dating of the artifacts that found in different cultural levels. The prehistoric archaeology mostly stands on the geological formation. The study of rocks, minerals, ores, gem stones, soil, land formations, land scape, river migration, river terrace formations, erosion, deposition, submergence of land mass, raised beaches, ancient coast lines and sea level fluctuations, all fall in the ambit of geology. Geology helps to understand the various factors that determine the human habit on the earth.

Archaeology and Biology

The scientific advancement made in the field of DNA, the material that carries the hereditary information, revolutionized the study of humanity. The skeletal remains recovered from different archaeological sites are being placed before the test to determine the hereditary traits of the past society. Therefore, molecular biology adds new insights into our understanding of the human populations.

Archaeology and Zoology

Animal remains were the first evidence used by the archaeologists to characterize the palaeo-climate. the study of the faunal remains aids to understand the contemporary environment at the time of deposition. The archaeo-zoologist helps to reconstruct certain social parameters like the domestication of animal, diet pattern, husbandry, social status, butchery, trade, etc., through the study of micro and macro faunal remains.

Archaeology and Botany

The study of plant remains recovered from archaeological sites is known as Archaeo-botany. pollen samples in the form of charred grains are being collected in archaeological excavations particularly in pits, storage bins, granaries and cooking vessels. Macrobotanical remains are well preserved in absolute dry environment like in deserts, water logged regions and sometimes in volcanic eruptions.

Archaeology and Physics

The most important contribution of physics is the dating method. The various dating methods like radiocarbon dating, the dating, archaeo-magnetic dating, potassium-argon dating, fission track dating and others are the contributions of physics to archaeology.

Archaeology and Chemistry

Chemistry plays an important in the conservation of antiquities and archaeological monuments. The dating methods like amino-acid racemization, nitrogen and fluorine tests are determined based on the chemical properties found in the archaeological material. The preservation of rock paintings, fresco paintings, palm leaf manuscripts, rare paper manuscripts, etc., are being carried out at the advice of conservationist.

Archaeology and Palaeopathology

Pathology is a science of diseases. certain diseases leave their marks on the bones, example, malnutrition, dental decay etc. Paleopathology is an application of this science to the study of the skeletal remains from ancient sites to recover data about the health condition of the people, cause of death and the incidence of any particular disease.

Archaeology and Metallurgy

The discovery of metal was an epoch-making event in human history as it brought about a significant change in the tool technology and tool equipment.

Conclusion

The original connotation of the word archaeology implies the study of the past, its scope considerably widening. It is a continuing story ‘which begins with the first appearance of the man on earth and will only end with the final extinction of the species”. (Leonard Cottrell)

Broadly speaking, the dependence of the archaeologists on other sciences is seen in a four speres of his activities:

- Exploration and excavation

- Dating the artefacts and the strata

- Studying the environmental archaeology

- Cleaning and preserving the antiquities and monuments

Oceanography, remote sensing, geographical information system, microbiology, metallurgy, computer science etc. are the latest emerging disciplines. They are all contributing enormously to reconstruct the human past most effectively and authentically. The growth of science had a direct impact on the growth of archaeology. The path breaking inventions made in different disciplines of science from time to time indirectly helped to the development of different kinds of archaeology.

The Palaeolithic Period, also known as the Old Stone Age, was the earliest period of human development, lasting approximately 8000 BC. The Palaeolithic Period is divided into two eras: the Lower Palaeolithic (from 40,000 BC to 8000 BC) and the Upper Palaeolithic (from 40,000 BC to 8000 BC). This age group used to live in caves and rock shelters near rivers and valleys.

Palaeolithic Period (Old Stone Age)500,000 BCE – 10,000 BCE

- The term “Palaeolithic” is derived from the Greek words “palaeo” (old) and “lithic” (stone).

- As a result, the term Palaeolithic age refers to the prehistoric stone age.

- The old stone age or palaeolithic culture of India developed during the Pleistocene period, also known as the Ice Age, a geological period when the earth was covered in ice and the weather was so cold that human or plant life could not survive.

- However, the earliest species of man may have existed in the tropical region where ice melted.

- The old stone age or palaeolithic age in India is divided into three phases according to the nature of the stone tools used by the people and also according to the nature of the change of climate.

- Lower Palaeolithic Age: up to 100,000 BC

- Middle Palaeolithic Age: 100,000 BC – 40,000 BC

- Upper Palaeolithic Age: 40,000 BC – 10,000 BC

Characteristics

- The Indians were thought to be of the ‘Negrito’ race and lived in the open air, river valleys, caves, and rock shelters.

- They were foragers, eating wild fruits and vegetables and subsisting on hunting.

- There was no understanding of houses, pottery, or agriculture. It wasn’t until later that they discovered fire.

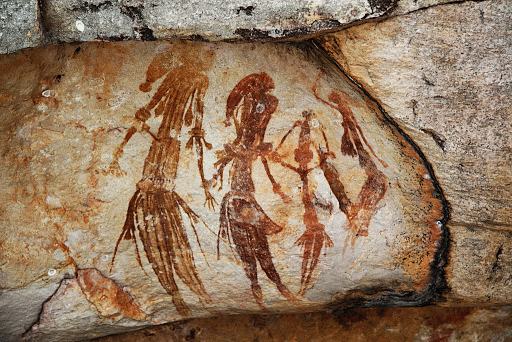

- Paintings from the upper palaeolithic period are evidence of art.

- Hand axes, choppers, blades, bruins, and scrapers were made from unpolished, rough stones.

- In India, palaeolithic men are also known as ‘Quartzite’ men because their stone tools were made of quartzite, a hard rock.

- People were unaware of agriculture or home construction, so life was not properly settled.

- It has been discovered that people survived by eating tree and fruit roots and living in caves and hills.

- The Palaeolithic, also known as the Old Stone Age, was a period in human evolution.

- Humans learned to make arms out of animal bones during this time period.

- As a result, the Palaeolithic period is the foundation of modern human civilization.

Palaeolithic Painting

Old Stone Age Indian sites (Palaeolithic Age)

| Lower Palaeolithic (up to 100,000 BC) |

|

| Middle Palaeolithic (100,000 BC – 40,000 BC ) |

|

| Upper Palaeolithic (40,000 BC – 10,000 BC) |

|

Lower Palaeolithic Age: up to 100,000 BC

- The Lower Palaeolithic Age was primarily found in Western Europe and Africa, and early humans led nomadic lives.

- Although no specific human group was responsible for the Lower Palaeolithic period, many scholars believe that it was contributed by Neanderthal-like Philanthropic men.

- It spans the majority of the Ice Age.

- Hand axes, choppers, and cleavers were used by hunters and food gatherers. The tools were crude and heavy.

- Bori in Maharashtra is one of the earliest lower Palaeolithic sites.

- Limestone was also used in the manufacture of tools.

- Caves and rock shelters are examples of habitation sites.

- Bhimbetka in Madhya Pradesh is a significant location.

Middle Palaeolithic Age: 100,000 BC – 40,000 BC

- The Middle Palaeolithic Age was primarily associated with the early form of man, Neanderthal, whose remains were frequently discovered in caves with evidence of fire use.

- They got the name from the Neander Valley (Germany).

- Neanderthal was a prehistoric hunter.

- The Middle Palaeolithic man was a scavenger, but there is little evidence of hunting and gathering. Before burial, the dead were painted.

- Flakes, blades, pointers, scrapers, and borers were among the tools used.

- The tools were more compact, lighter, and thinner.

- In comparison to other tools, the use of hand axes has decreased.

Upper Palaeolithic Age: 40,000 BC – 10,000 BC

- The appearance of new flint industries and Homo Sapiens (modern type men) in the world context characterised the Upper Palaeolithic Age.

- This was the final period of the Palaeolithic Age, and it gave rise to Upper Palaeolithic culture.

- This period accounted for roughly one-tenth of the total Palaeolithic Period, but the primitive man made the most cultural progress in a short period of time.

- The culture has been dubbed the Osteodontokeratic culture, referring to tools made of bone, teeth, and horns.

- The upper palaeolithic period corresponded to the end of the ice age, when the climate became comparatively warmer and less humid.

- Homo sapiens appears. The period is distinguished by technological and tool innovation.

- There are numerous bone tools, such as needles, harpoons, parallel-sided blades, fishing tools, and burintools.

Tools

- Tools dating back nearly 100,000 years have been discovered in the Chhota Nagpur Plateau, Kurnool, and Andhra Pradesh.

- Lower Palaeolithic people preferred to live near water sources because stone tools were plentiful in river valleys.

- The first stone tool fabrication began during this time period (including the earliest stone tools found today) and was known as the Oldowan tradition, which refers to a pattern of stone-tool manufacturing by Hominids (Homo habilis).

- The earliest tools were thought to be splintered stones called eoliths.

- Large and small scrapers, hammer stones, choppers, awls, and other tools were used to make these tools.

- Hand axes and cleavers were common tools among these early hunters and gatherers.

- Cleavers, choppers, and hand axes were the most common tools used during the Lower Palaeolithic era.

- These tools were primarily used to cut, dig, and skin prey.

- These tools were discovered in the Belan Valley of Mirzapur (Uttar Pradesh), Didwana in Rajasthan, the Narmada Valley, and Bhimbetka (near Bhopal, M.P.).

- The Middle Palaeolithic Period tools were heavily reliant on flakes, which were used to make bores, points, and scrapers, among other things. During this time, there is also a crude pebble industry.

- The stones discovered were called microliths because they were so small. This period’s stone tools are of the flake tradition.

- For example, needles were used to sew furs and skins used as body coverings.

- Large flake blades, scrapers, and burins dominated Upper Palaeolithic Age tools.

- This man’s lifestyle was similar to that of Neanderthals and Homo erectus, and the tools he used were crude and unsophisticated at the time.

- There is evidence of the first appearance of bone artefacts and the first form of art in Africa.

- The first evidence of fishing can also be found in places like South Africa’s Blombos Cave through artefacts.

- The use of polished fine cutting edge tools, as well as mortars and pestles for grinding grain, emerged.

Palaeolithic Period – Tools

Social organisation

- Scientists know very little about the social organisation of the earliest Palaeolithic (Lower Palaeolithic) societies.

- Unlike Lower Palaeolithic and early Neolithic societies, Middle Palaeolithic societies were nomadic and comprised bands.

- According to some sources, most Middle and Upper Palaeolithic societies were possibly fundamentally egalitarian and engaged in organised violence between groups only rarely or never.

- Some Upper Palaeolithic societies may have had more complex and hierarchical organisation (such as tribes with a pronounced hierarchy and a somewhat formal division of labour) and may have engaged in endemic warfare.

- Women were responsible for gathering wild plants and firewood in Palaeolithic societies, while men were responsible for hunting and scavenging dead animals.

- Palaeolithic and Mesolithic groups, like most contemporary hunter-gatherer societies, most likely followed matrilineal and ambilineal descent patterns; patrilineal descent patterns were probably rarer than in the Neolithic.

- Palaeolithic hunters and gatherers ate a variety of vegetables (including tubers and roots), fruits, seeds (including nuts and wild grass seeds), and insects, as well as meat, fish, and shellfish.

- There is, however, little direct evidence of the proportions of plant and animal foods.

Conclusion

The Palaeolithic Period, also known as the Old Stone Age, was the period of human development that began around 8000 BC. The Palaeolithic period, also known as the Old Stone Age, was a stage in the evolution of humans. During this time, humans learned to make arms out of animal bones. As a result, the Palaeolithic period is regarded as the birthplace of modern human civilization.

The Belan Valley, located in the Vindhyan region of Uttar Pradesh, is one of the most significant prehistoric sites in India, offering an extensive and well-preserved cultural sequence from the Palaeolithic to the Neolithic periods. This valley, which lies in the southern part of the Middle Ganga Plain, has been a center of human activity for thousands of years, providing valuable archaeological evidence about the technological, economic, and social transformations of prehistoric societies.

The importance of the Belan Valley lies in its continuity of cultural evolution, making it a crucial site for understanding the prehistoric past of the Indian subcontinent. Excavations at sites like Koldihwa, Chopani Mando, and Mahagara have provided detailed insights into how early humans adapted to changing climatic conditions, developed sophisticated tool-making techniques, and gradually transitioned from a hunting-gathering lifestyle to agriculture and domestication. The valley’s unique ecological setting, with fertile alluvial soil, abundant flora and fauna, and access to stone resources, played a key role in shaping the lifeways of its prehistoric inhabitants.

Geographical and Environmental Setting of the Belan Valley

The Belan River, a tributary of the Tons River, originates in the Vindhyan hills and flows through a diverse landscape that includes rocky outcrops, river terraces, and open plains. This varied topography created an ideal environment for early human occupation, providing shelter, water, and access to critical resources like stone for tool-making and animals for food.

During the Pleistocene epoch, the region experienced significant climatic fluctuations, alternating between humid and arid conditions. These changes influenced vegetation patterns, river dynamics, and faunal diversity, forcing human groups to constantly adapt. The presence of both open grasslands and dense forests provided a rich ecological zone where early humans could practice hunting, gathering, and eventually agriculture.

The archaeological evidence from the Belan Valley suggests that prehistoric communities occupied this region continuously, developing new technologies and cultural practices over time. The sequence of cultural development in the Belan Valley spans from the Lower Palaeolithic to the Neolithic, demonstrating a clear trajectory of human adaptation and innovation.

Lower Palaeolithic Culture in the Belan Valley

The earliest phase of human occupation in the Belan Valley dates back to the Lower Palaeolithic period (around 1.5 million to 100,000 years ago). This period is marked by the presence of Acheulean tools, including hand axes, cleavers, and choppers, which were primarily made of quartzite and sandstone. These tools, found at sites such as Koldihwa and Chopani Mando, indicate that early hominins, likely Homo erectus, used them for butchering animals, cutting wood, and processing plant materials.

The Acheulean culture in the Belan Valley shares similarities with other Lower Palaeolithic sites in India, such as those in the Son Valley and Narmada Valley. The tools from this period exhibit bifacial flaking techniques, where both sides of a stone were carefully shaped to create sharp edges. This suggests a gradual improvement in stone tool technology and a better understanding of raw material properties.

Although there is no definitive evidence of permanent settlements, the presence of repeated occupation layers suggests that Lower Palaeolithic groups followed a seasonal pattern of movement, likely in search of food and water. The presence of large mammalian fossils, including elephants, cattle, and deer, suggests that early humans in the Belan Valley relied on big-game hunting as a primary subsistence strategy.

Middle Palaeolithic Culture in the Belan Valley

The Middle Palaeolithic period (100,000–40,000 years ago) saw significant technological advancements, particularly in the production of flake tools, scrapers, points, and borers. This period is characterized by a shift from large bifacial tools to smaller, more refined stone tools, which allowed for greater efficiency in cutting, scraping, and processing animal hides.

Sites such as Chopani Mando and Mahagara have yielded numerous Middle Palaeolithic tools, indicating that human populations were becoming more specialized in their tool-making techniques. The Levallois technique, which involved preparing a stone core to produce uniform flakes, was widely used during this period. This suggests that early humans had developed a greater understanding of stone fracturing mechanics, allowing them to produce high-quality tools with minimal waste.

The Middle Palaeolithic people of the Belan Valley likely practiced a mixed subsistence strategy, combining hunting, gathering, and possibly early attempts at food storage. The presence of charred bones and hearths suggests that they were beginning to use controlled fire for cooking, warmth, and protection from predators.

Upper Palaeolithic Culture in the Belan Valley

The Upper Palaeolithic period (40,000–10,000 BCE) marks the beginning of more advanced tool-making traditions and cultural developments in the Belan Valley. The most significant innovation of this period was the introduction of microliths, which were small, geometrically-shaped stone tools that could be mounted on wooden or bone shafts to create composite tools such as arrows, spears, and sickles.

Excavations at sites like Mahagara and Chopani Mando have revealed a diverse range of microliths, including backed blades, burins, and points, indicating that Upper Palaeolithic groups had developed more specialized hunting and gathering techniques. The presence of rock art and symbolic artifacts suggests that these communities also engaged in ritualistic and artistic expressions, possibly indicating the emergence of complex social structures and belief systems.

The Upper Palaeolithic period in the Belan Valley also witnessed increasing population density and longer settlement durations, as indicated by deeper occupation layers at major archaeological sites. This suggests a gradual transition toward semi-permanent habitation, laying the foundation for the Neolithic way of life.

Neolithic Culture in the Belan Valley

The Neolithic period (around 7,000–2,000 BCE) represents the most significant cultural transformation in the Belan Valley, marking the transition from a hunting-gathering economy to food production and domestication. Sites like Koldihwa and Mahagara have provided conclusive evidence of early agriculture and animal husbandry, making the Belan Valley one of the earliest centers of agricultural development in the Indian subcontinent.

At Koldihwa, excavators discovered charred grains of rice (Oryza sativa), making it one of the oldest known sites for rice cultivation in South Asia. The presence of burnt clay structures, grinding stones, and pottery indicates that Neolithic communities had established permanent settlements, developed ceramic technology, and practiced food storage and processing.

Similarly, at Mahagara, evidence of cattle domestication has been found, with excavations revealing cattle hoof impressions on clay floors, suggesting that early farmers had begun managing livestock for milk, meat, and agricultural work. The shift from a foraging-based economy to a food-producing one had profound implications for social organization, population growth, and technological advancements in the Belan Valley.

Conclusion

The Belan Valley presents a continuous and uninterrupted cultural sequence from the Lower Palaeolithic to the Neolithic, providing invaluable insights into the prehistoric past of India. The region’s rich ecological setting, abundant natural resources, and favorable climatic conditions made it an ideal place for early human occupation and cultural evolution. The discovery of early agricultural practices and animal domestication at Koldihwa and Mahagara marks a significant milestone in the history of human civilization, highlighting the Belan Valley’s crucial role in the development of early farming societies in the Indian subcontinent.

The Son Valley, a major geographical and archaeological region in central India, has played a crucial role in understanding the Stone Age cultures of the Indian subcontinent. Located in the modern-day states of Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, and Bihar, this valley is home to one of the most well-preserved sequences of prehistoric cultures, ranging from the Lower Paleolithic to the Mesolithic period. The valley, particularly around sites such as Bhimbetka, Paisra, Koldihwa, and Mahadaha, offers critical insights into the evolution of early human life, technological advancements, and cultural transformations over thousands of years.

Lower Paleolithic Culture (Early Stone Age) in the Son Valley

The Lower Paleolithic period, roughly spanning from 1.5 million years ago to 100,000 years ago, marks the earliest evidence of human occupation in the Son Valley. During this period, early hominins, likely Homo erectus, inhabited the region and developed basic stone tools for hunting and food processing. The primary tool types associated with this era are the Acheulean hand axes and cleavers, characteristic of the Soanian and Acheulean industries.

Archaeological evidence suggests that the Acheulean tradition in the Son Valley was influenced by similar industries in Africa and other parts of India, such as the Narmada and Chambal Valleys. Excavations at sites like Piprahwa, Salamatpur, and Bhimbetka have revealed a rich collection of bifacial tools made of quartzite, indicating that early hominins relied on locally available raw materials. These tools were primarily used for butchering animals, processing plant materials, and possibly digging.

The environment during the Lower Paleolithic was significantly different from today. The region was covered with dense forests and grasslands, providing abundant food resources. Fossil remains suggest the presence of prehistoric elephants, wild cattle, and large carnivores, which were likely hunted by early humans. Evidence of controlled fire usage in some sites indicates that early humans had begun experimenting with cooking and protection against predators.

Middle Paleolithic Culture (Middle Stone Age) in the Son Valley

The Middle Paleolithic period, which lasted from around 100,000 to 40,000 years ago, marks a significant technological and cultural transformation in the Son Valley. During this phase, early modern humans (Homo sapiens) began to appear, replacing earlier hominins. The dominant tool types of this period were flake tools, scrapers, and borers, which were produced using the Levallois and discoidal core techniques.

Excavations at sites such as Paisra (Bihar) and Morahana Pahar (Madhya Pradesh) have revealed the presence of well-crafted flake tools made from chert and quartzite, signifying an advancement in stone tool production. The Middle Paleolithic also witnessed the emergence of specialized tools designed for cutting, scraping, and hide processing, which suggests a shift towards a more diverse subsistence strategy.

Climatic conditions during this period were becoming more arid, leading to a gradual change in the flora and fauna. Hunter-gatherers in the Son Valley began adapting to these environmental changes by developing better hunting strategies and possibly engaging in seasonal migrations. The presence of hunting sites and temporary shelters indicates a more mobile lifestyle, as groups moved in search of water and food resources.

Upper Paleolithic Culture (Late Stone Age) in the Son Valley

The Upper Paleolithic period (40,000–10,000 BCE) is marked by an explosion of cultural, technological, and artistic developments. The tool industry of this period is dominated by microliths, which are small, finely crafted stone tools. Unlike their predecessors, Upper Paleolithic communities in the Son Valley used blades, burins, and backed tools, which were more efficient and versatile.

One of the most significant sites of this period is Bhimbetka, a UNESCO World Heritage Site in Madhya Pradesh. Bhimbetka is renowned for its prehistoric rock art, which provides evidence of early symbolic thinking, religious beliefs, and artistic expression. The rock paintings, depicting hunting scenes, animals, and human figures, suggest that Upper Paleolithic people in the Son Valley had developed complex cognitive abilities and social structures.

The Upper Paleolithic period also saw an increased reliance on plant-based foods, fishing, and small-game hunting. Evidence from archaeological sites indicates the use of bone tools and ornaments, suggesting a growing interest in self-adornment and social identity.

Mesolithic Culture (10,000–5,000 BCE) in the Son Valley

The Mesolithic period represents the transition from hunting-gathering societies to early forms of agriculture and animal domestication. This period is characterized by the widespread use of microlithic tools, which were often used as composite tools attached to wooden or bone handles. The primary sites of Mesolithic occupation in the Son Valley include Baghor, Chopani Mando, and Mahadaha, which provide a rich assemblage of tools, pottery, and skeletal remains.

One of the most significant Mesolithic sites in the Son Valley is Mahadaha (Uttar Pradesh), where a large burial complex has been discovered. The burials indicate the presence of complex social structures, ritualistic practices, and possibly early forms of ancestor worship. The Baghor site (Madhya Pradesh) has yielded evidence of circular stone structures, which might have been used as temporary shelters or ritual spaces.

During the Mesolithic period, climatic conditions became warmer and wetter, leading to the expansion of riverine and lacustrine environments. This change enabled early humans to exploit fish, waterfowl, and aquatic plants as new food sources. Some scholars suggest that the Mesolithic populations of the Son Valley may have started experimenting with proto-agriculture, as seen in the remains of wild rice and barley at sites like Koldihwa and Mahagara.

Neolithic and Chalcolithic Continuation

Although the Mesolithic was the last phase of the Stone Age proper, many Neolithic and Chalcolithic sites in the Son Valley suggest a gradual shift towards full-fledged agriculture and metallurgy. Sites such as Koldihwa and Mahagara in the Belan Valley (a tributary of the Son River) provide some of the earliest evidence of rice cultivation and domesticated cattle in India, dating back to 7000 BCE.

The transition to settled life led to the development of pottery, improved dwellings, and more sophisticated social structures. The use of copper tools and early forms of metalworking in the later Chalcolithic period marks the beginning of proto-urban settlements, setting the stage for the emergence of the Harappan and later Vedic cultures.

Conclusion

The Son Valley offers one of the most comprehensive and well-preserved records of Stone Age cultural evolution in India. From the early Acheulean hand axes of the Lower Paleolithic to the intricate microliths of the Mesolithic, the region showcases a rich and dynamic history of human adaptation, innovation, and survival. The presence of prehistoric rock art, burial complexes, and early agricultural experiments further highlights the Son Valley’s crucial role in understanding the prehistoric past of the Indian subcontinent.

By analyzing these cultural sequences, archaeologists continue to uncover valuable insights into the lives, technologies, and beliefs of early human societies, shedding light on the long and complex journey of human civilization in the heart of India.