Sociology – 1st Year

Paper – I (PYQs Soln.)

Part A

Language/भाषा

The term “Society” generally refers to a large, organized group of individuals who share a common culture, values, and social structures. It encompasses the entire network of relationships, norms, and institutions that guide the behavior and interaction of people within a specific geographical or cultural context. Society represents the broader concept of human collectivism, encompassing communities, traditions, and a shared sense of identity that binds individuals together.

On the other hand, “A Society” typically denotes a specific organized group formed for a particular purpose or shared interest. This could include groups like a literary society, cultural society, or scientific society that operates with a defined membership and often has established rules and goals. Unlike the broader concept of society, “a society” is usually more formalized and purpose-driven, focusing on specific objectives and interests of its members.

In essence, “Society” is the overarching social framework, while “A Society” is an individual group within that framework, with a distinct identity and purpose.

Some of the important characteristics or elements of community are as follows:

Meaning of community can be better understood if we analyze its characteristics or elements. These characteristics decide whether a group is a community or not. However, community has the following characteristics or elements:

A group of people

A group of people is the most fundamental or essential characteristic or element of community. This group may be small or large but community always refers to a group of people. Because without a group of people we can’t think of a community, when a group of people live together and share a common life and binded by a strong sense of community consciousness at that moment a community is formed. Hence a group of people is the first pre-requisites of community.

A definite locality

It is the next important characteristic of a community. Because community is a territorial group. A group of people alone can’t form a community. A group of people forms a community only when they reside in a definite territory. The territory need not be fixed forever. A group of people like nomadic people may change their habitations. But majority community are settled and a strong bond of unity and solidarity is derived from their living in a definite locality.

Community Sentiment

It is another important characteristic or element of community. Because without community sentiment a community can’t be formed only with a group of people and a definite locality. Community sentiment refers to a strong sense of awe feeling among the members or a feeling of belonging together. It refers to a sentiment of common living that exists among the members of a locality. Because of common living within an area for a long time a sentiment of common living is created among the members of that area. With this the members emotionally identify themselves. This emotional identification of the members distinguishes them from the members of other community.

Naturality

Communities are naturally organised. It is neither a product of human will nor created by an act of government. It grows spontaneously. Individuals became the member by birth.

Permanence

Community is always a permanent group. It refers to a permanent living of individuals within a definite territory. It is not temporary like that of a crowd or association.

Similarity

The members of a community are similar in a number of ways. As they live within a definite locality they lead a common life and share some common ends. Among the members similarity in language, culture, customs, and traditions and in many other things is observed. Similarities in these respects are responsible for the development of community sentiment.

Wider Ends

A community has wider ends. Members of a community associate not for the fulfillment of a particular end but for a variety of ends. These are natural for a community.

Total organised social life

A community is marked by total organised social life. It means a community includes all aspects of social life. Hence a community is a society in miniature.

A Particular Name

Every community has a particular name by which it is known to the world. Members of a community are also identified by that name. For example people living in Odisha is known as odia.

No Legal Status

A community has no legal status because it is not a legal person. It has no rights and duties in the eyes of law. It is not created by the law of the land.

Size of Community

A community is classified on the basis of it’s size. It may be big or small. Village is an example of a small community whereas a nation or even the world is an example of a big community. Both the type of community are essential for human life.

Concrete Nature

A community is concrete in nature. As it refers to a group of people living in a particular locality we can see its existence. Hence it is concrete.

A community exists within society and possesses distinguishable structure which distinguishes it from others.

In sociology, the determinants of status are factors that shape an individual’s social position and influence within a social hierarchy. One key determinant is wealth or economic capital, as financial resources often correlate with higher social standing. Alongside wealth, education is a crucial factor; a higher level of educational attainment generally garners respect and better access to professional opportunities, elevating social status.

Occupation also significantly influences status, with certain professions, like medicine, law, and engineering, often viewed as prestigious. Additionally, family background plays a role in determining status, especially in traditional societies where social position is partially inherited. Cultural capital—including personal style, taste, and manners—affects how individuals are perceived socially, as these traits reflect learned behaviors associated with higher status groups.

Race, ethnicity, and gender are also important determinants, as these social categories can affect one’s status due to societal norms and biases. Achievements and contributions in fields like sports, arts, or politics further enhance status, as society often values individual accomplishments. Thus, the determinants of status are a blend of economic, cultural, and social factors that highlight both individual capabilities and systemic influences.

Meaning of Social Groups

Two or more persons in interaction constitute a social group. It has common aim. In its strict sense, group is a collection of people interacting together in an orderly way on the basis of shared expectations about each other’s behaviour. As a result of this interaction, the members of a group, feel a common sense of belonging.

A group is a collection of individuals but all collectivities do not constitute a social group. A group is distinct from an aggregate (people waiting at railway station or bus stand) member of which do not interact with one another. The essence of the social group is not physical closeness or contact between the individuals but a consciousness of joint interaction.

This consciousness of interaction may be present even there is no personal contact between individuals. For example, we are members of a national group and think ourselves as nationals even though we are acquainted with only few people. “A social group, remarks Williams, “is a given aggregate of people playing interrelated roles and recognized by themselves or others as a unit of interaction.

The Sociological conception of group has come to mean as indicated by Mckee, ” a plurality of people as actors involved in a pattern of social interaction, conscious of sharing common understanding and of accepting some rights and obligations that accrue only to members.

According to Green, “A group is an aggregate of individuals which persist in time, which has one or more interests and activities in common and which is organised.”

According to Maclver and Page “Any collection of human beings who are brought into social relationship with one another”. Social relationships involve some degree of reciprocity and mutual awareness among the members of the group.

Thus, a social group consists of such members as have reciprocal relations. The members are bound by a sense of unity. Their interest is common, behaviour is similar. They are bound by the common consciousness of interaction. Viewed in this way, a family, a village, a nation, a political party or a trade union is a social group.

In short, a group means a group of associated members, reciprocally interacting on one another. Viewed in this way, all old men between fifty and sixty or men belonging to a particular income level are regarded as ‘ aggregates’ or ‘quasi-groups’. They may become groups when they are in interaction with one another and have a common purpose. People belonging to a particular income level may constitute a social group when they consider themselves to be a distinct unit with special interest.

There are large numbers of groups such as primary and secondary, voluntary and involuntary groups and so on. Sociologists have classified social groups on the basis of size, local distribution, permanence, degree of intimacy, type of organisation and quality of social interaction etc.

Characteristics of Social Groups

Following are the important characteristics of social group:

1. Mutual Awareness:

The members of a social group must be mutually related to one another. A more aggregate of individuals cannot constitute a social group unless reciprocal awareness exist among them. Mutual attachment, is therefore, regarded as its important and distinctive feature. It forms an essential feature of a group.

2. One or more Common Interests:

Groups are mostly formed for the fulfillment of certain interests. The individuals who form a group should possess one or more than one common interests and ideals. It is for the realization of common interests that they meet together. Groups always originates, starts and proceed with a common interests.

3. Sense of Unity:

Each social group requires sense of unity and a feeling of sympathy for the development of a feeling or sense of belongingness. The members of a social group develop common loyalty or feeling of sympathy among themselves in all matters because of this sense of unity.

4. We-feeling:

A sense of we-feeling refers to the tendency on the part of the members to identify themselves with the group. They treat the members of their own group as friends and the members belonging to other groups as outsiders. They cooperate with those who belong to their groups and all of them protect their interests unitedly. We-feeling generates sympathy, loyalty and fosters cooperation among members.

5. Similarity of Behaviour:

For the fulfillment of common interest, the members of a group behave in a similar way. Social group represents collective behaviour. The-modes of behaviour of the members on a group are more or less similar.

6. Group Norms:

Each and every group has its own ideals and norms and the members are supposed to follow these. He who deviates from the existing group-norms is severely punished. These norms may be in the form of customs, folk ways, mores, traditions, laws etc. They may be written or unwritten. The group exercises some control over its members through the prevailing rules or norms.

The family is a fundamental social institution that plays a crucial role in shaping individuals and society as a whole. As the primary unit of socialization, the family is responsible for instilling values, norms, and cultural beliefs in its members, particularly during childhood. Through these shared experiences, family creates a strong sense of identity and belonging.

Families are also essential for providing emotional support, economic stability, and social security. They act as a support system, helping individuals manage challenges and fulfill their basic needs. Traditionally, family roles are defined, with members often adopting specific responsibilities such as caregiving, earning, and managing household duties. These roles reinforce social order and establish patterns for social behavior and gender roles in society.

Moreover, family structures can vary across societies, taking forms such as nuclear families, extended families, or single-parent families, reflecting cultural, economic, and social factors. As a social institution, the family is instrumental in maintaining societal continuity by reproducing and transmitting social and cultural norms across generations, making it a cornerstone of human society.

The institution of marriage holds significant sociological importance as it establishes formalized social bonds and defines legal and social relationships between individuals. Marriage serves as a foundational structure for family formation, providing a stable environment for reproduction and child-rearing. This continuity reinforces the socialization process, as parents pass down values, norms, and beliefs to the next generation.

Marriage also formalizes economic and social responsibilities between partners, creating a cooperative unit for resource sharing and mutual support. It helps maintain social order by clarifying roles within the family, contributing to social stability and reducing social conflict over relationships and inheritance.

In many cultures, marriage is associated with cultural and religious rituals that reinforce community values and affirm social ties, strengthening social cohesion. Furthermore, marriage is often linked to social status, impacting individuals’ positions within their communities. Thus, marriage as a social institution not only supports individual relationships but also upholds societal continuity, cohesion, and social structure.

Introduction

The socialization that we receive in childhood has a lasting effect on our ability to interact with others in society. How do we learn to interact with other people? Socialization is a lifelong process during which we learn about social expectations and how to interact with other people. Nearly all of the behavior that we consider to be ‘human nature’ is actually learned through socialization. And, it is during socialization that we learn how to walk, talk, and feed ourselves, about behavioral norms that help us fit in to our society, and so much more.

Socialization occurs throughout our life, but some of the most important socialization occurs in childhood. So, let’s talk about the most influential agents of socialization:-

Family

The child’s first world is that of his family. It is a world in itself, in which the child learns to live, to move and to have his being. Within it, not only the biological tasks of birth, protection and feeding take place, but also develop those first and intimate associations with persons of different ages and sexes which form the basis of the child’s personality development.

The family is the primary agency of socialisation. It is here that the child develops an initial sense of self and habit-training—eating, sleeping etc. To a very large extent, the indoctrination of the child, whether in primitive or modem complex society, occurs within the circle of the primary family group. The child’s first human relationships are with the immediate members of his family—mother or nurse, siblings, father and other close relatives.

Here, he experiences love, cooperation, authority, direction and protection. Language (a particular dialect) is also learnt from family in childhood. People’s perceptions of behaviour appropriate of their sex are the result of socialisation and major part of this is learnt in the family. As the primary agents of childhood socialisation, parents play a critical role in guiding children into their gender roles deemed appropriate in a society. They continue to teach gender role behaviour either consciously or unconsciously, throughout childhood.

Families also teach children values they will hold throughout life. They frequently adopt their parents’ attitudes not only about work but also about the importance of education, patriotism and religion.

Neighborhoods

Neighborhood can be said to be a local social unit where there is constant interaction among people living near one another or people of the same locality. In such spatial units, face to face interactions frequently take place. In this sense they are local social units where children grow up. You may observe diverse set of people in your neighborhood who differ in caste, class or religion or occupation. By interacting with such diverse set of people, you may be exposed to various customs and practices; various occupations that people pursue; the skills required for such occupations and also the qualities possessed by those members. The growing child may also imbibe values of discipline and orderly behaviour. Interactions are at both physical and social environment wherein children get easily affected. If the child is surrounded by people who are warm and cooperative, it will get definitely transmitted to him/her. On the other hand if the locality is peopled by aggressive and violent group, it is possible that such children may learn unsocial or anti-social behaviors’.

School

After family the educational institutions take over the charge of socialization. In some societies (simple non-literate societies), socialization takes place almost entirely within the family but in highly complex societies children are also socialized by the educational system. Schools not only teach reading, writing and other basic skills, they also teach students to develop themselves, to discipline themselves, to cooperate with others, to obey rules and to test their achievements through competition.

Schools teach sets of expectations about the work, profession or occupations they will follow when they mature. Schools have the formal responsibility of imparting knowledge in those disciplines which are most central to adult functioning in our society. It has been said that learning at home is on a personal, emotional level, whereas learning at school is basically intellectual.

Peer Groups

Besides the world of family and school fellows, the peer group (the people of their own age and similar social status) and playmates highly influence the process of socialization. In the peer group, the young child learns to confirm to the accepted ways of a group and to appreciate the fact that social life is based on rules. Peer group becomes significant others in the terminology of G.H. Mead for the young child. Peer group socialization has been increasing day by day these days.

Young people today spend considerable time with one another outside home and family. Young people living in cities or suburbs and who have access to automobiles spend a great deal of time together away from their families. Studies show that they create their own unique sub-cultures—the college campus culture, the drug culture, motorcycle cults, athletic group culture etc. Peer groups serve a valuable function by assisting the transition to adult responsibilities.

Mass Media

From early forms of print technology to electronic communication (radio, TV, etc.), the media is playing a central role in shaping the personality of the individuals. Since the last century, technological innovations such as radio, motion pictures, recorded music and television have become important agents of socialisation.

Television, in particular, is a critical force in the socialisation of children almost all over the new world. According to a study conducted in America, the average young person (between the ages of 6 and 18) spends more time watching the ‘tube’ (15,000 to 16,000 hours) than studying in school. Apart from sleeping, watching television is the most time-consuming activity of young people.

Relative to other agents of socialization discussed above, such as family, peer group and school, TV has certain distinctive characteristics. It permits imitation and role playing but does not encourage more complex forms of learning. Watching TV is a passive experience. Psychologist Urie Bronfenbrenner (1970) has expressed concern about the ‘insidious influence’ of TV in encouraging children to forsake human interaction for passive viewing.

Workplace

A fundamental aspect of human socialization involves learning to behave appropriately within an occupation. Occupational socialization cannot be separated from the socialization experience that occurs during childhood and adolescence. We are mostly exposed to occupational roles through observing the work of our parents, of people whom we meet while they are performing their duties, and of people portrayed in the media.

The State

Social scientists have increasingly recognized the importance of the state as an agent of socialisation because of its growing impact on the life cycle. The protective functions, which were previously performed by family members, have steadily been taken over by outside agencies such as hospitals, health clinics and insurance companies. Thus, the state has become a provider of child care, which gives it a new and direct role in the socialisation of infants and young children.

Not only is this, as a citizen, the life of a person greatly influenced by national interests. For example, labor unions and political parties serve as intermediaries between the individual and the state. By regulating the life cycle to some degree, the state shapes the station process by influencing our views of appropriate behaviour at particular ages.

Religion

While some religions are informal institutions, here we focus on practices followed by formal institutions. Religion is an important avenue of socialization for many people. The United States is full of synagogues, temples, churches, mosques, and similar religious communities where people gather to worship and learn. Like other institutions, these places teach participants how to interact with the religion’s material culture (like a mezuzah, a prayer rug, or a communion wafer). For some people, important ceremonies related to family structure—like marriage and birth—are connected to religious celebrations. Many religious institutions also uphold gender norms and contribute to their enforcement through socialization. From ceremonial rites of passage that reinforce the family unit to power dynamics that reinforce gender roles, organized religion fosters a shared set of socialized values that are passed on through society.

The relationship between society, culture, and personality is deeply interwoven, as each influences and shapes the others. Society represents the broader structure within which individuals live and interact, governed by a system of social institutions and relationships that organize collective life. Within society, culture provides the shared values, beliefs, customs, and norms that guide behavior and give society its unique identity. Culture acts as the blueprint for society, shaping the ways in which people interact, think, and perceive the world.

Personality, on the other hand, is the unique pattern of thoughts, emotions, and behaviors that characterize an individual. It develops through socialization, a process deeply influenced by both society and culture. Society offers the social environment where personality forms, while culture provides the content of that personality by instilling values, norms, and social roles. For example, an individual’s identity, attitudes, and behavioral traits are molded by cultural expectations and societal norms, affecting their personality development.

Thus, society provides the framework, culture offers the content, and personality reflects how these elements are internalized by individuals. Together, society, culture, and personality create a dynamic relationship where each continuously shapes and reinforces the other, contributing to social cohesion and the diversity of individual identities within a collective framework.

The relationship between status and role is essential to understanding social interactions, as both concepts define an individual’s position and expected behavior within society. Status refers to the recognized position a person holds within a social structure, such as being a teacher, parent, or manager. Each status carries a level of prestige and identifies the individual’s place within the social hierarchy.

Role, on the other hand, encompasses the behaviors, responsibilities, and expectations associated with a given status. For instance, a teacher’s status involves the roles of educating, guiding, and evaluating students. Roles translate social expectations into specific actions and interactions, providing a framework for consistent behavior across different individuals holding the same status.

Thus, while status gives a person a social identity and standing, role defines how that identity is enacted. The relationship between the two is dynamic, as society expects individuals to perform their roles according to the status they hold. Together, status and role contribute to social order by ensuring that individuals understand and fulfill their positions within the larger social system and contribute to collective functioning.

DEFINITION OF SOCIOLOGY

The term sociology was coined by Auguste Comte, who is called the father of Sociology. Sociology is concerned with the study of human relationships and the society. It is believed that relationships develop when individuals come in close contact with other and interaction takes place between them. This leads to the formation of social groups and complex relationships among these groups develop as result of constant interaction. Hence, it can be said that social self and individual self are two parts of the same coin. Given this, scholars have attempted to define and explain the subject matter of sociology.

One of the founding fathers of sociology, Auguste Comte divided the subject matter of sociology into the study of social static and social dynamic. The static was concerned with the study of how the parts of the societies inter-relate, the dynamic was to focus on whole societies as the unit of analysis and to show how they developed and changed through time (Inkeles, 1964). According to Emile Durkheim sociology is the study of social facts. Sociology can be defined as the scientific study of human life, social relations, social groups and every aspect of the society as a whole. The scope of sociology is very wide, ranging from the analysis of the everyday interaction between individuals on the street to the investigation and comparison of societies across the globe.

Psychology

The term psychology is derived from two Greek words; Psyche means “soul or breath” and Logos means “knowledge or study” (study or investigation of something). Psychology developed as an independent academic discipline in 1879, when a German Professor named Wilhelm Wundt established the first laboratory for psychology at the University of Leipzig in Germany.

Initially, psychology was defined as ‘science of consciousness’. . In the simple words, we can define psychology as the systematic study of human behaviour and experience. According to Baron (1990), psychology is the science of behaviour and cognitive processes. Psychology emphasizes on the process that occurs inside the individual’s mind such as perception, cognition, emotion, and consequence of these process on the social environment.

SOCIOLOGY AND PSYCHOLOGY: THE POSSIBLE INTERLINK

Sociology and psychology together form the core of the social sciences. Right from their inception as separate academic disciplines, sociology and psychology have studied different aspects of human life. Most of the other species, work on instincts in the physical environment for their survival. While the survival of humans depends upon the learned behaviour patterns. An instinct involves a genetically programmed directive which informs behaviour in a particular way. It also involves specific instruction to perform a particular action (Haralambos and Holborn, 2008). For instance, birds have instincts to build nests and members of particular species are programmed to build a nest in a particular style and pattern. Unlike this, the human mind is influenced by the social culture, customs, norms, and values. It through socialization that humans learn specific behaviour patterns to suit them best in the physical environment. Humans process the information provided by the social context to make sense of their living conditions. Sociology’s basic unit of analysis is the social system such as family, social groups, cultures etc.

The main subject matter of psychology is to study human mind to analyses attitude, behavior emotions, perceptions and values which lead to the formation of individual personality living in the social environment. While sociology deals with the study of the social environment, social collectives which include family, communities and other social institutions psychology deals with the individual. For instance, while studying group dynamism, sociologist and psychologist initially share common interestsin various types of groups, and their structures which are affected by the degree of cooperation, cohesion, conflict, information flow, the power of decision making and status hierarchies. This initial similarity of interest, takes on different focus, both the disciplines use different theoretical positions to explain the group phenomena.

SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY: HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT

The quest to study human behaviour on scientific principles started with the emergence and establishment of natural sciences during the nineteenth century. Comte thought that society could be studied using the scientific methods of natural sciences. Comte argued careful observation of the entities that are known directly to experience could be used to explain the relationship between the observed phenomena. By understanding the causal relationship between various events it is possible to predict future events. He also held the belief that once the rules governing the social life are identified, the social scientist can work towards the betterment of the society. This quest to produce knowledge about the society and place of the individual within it, on the basis evidence and observation is central to the origin of Social psychology. The ideas of early and later sociologist helped to shape the sociological social psychology. Mead studied the effect of social conditions on our sense of self. Other influence contributors in the development of sociological social psychology include Georg Simmel (1858-1918),Charles Horton Cooley (1864-1929), and Ervin Goffman.

The emergence of modern social psychology could be traced from the nineteenth century onwards. One of the first systematic manual of social psychology Social and Ethical Interpretation in Mental Development was published in New York in the year 1987 by James Mark Baldwin. However, in the year 1908, it was the work of two authors; William McDougall and Edward A. Ross that gave social psychology the status of an independent scientific discipline. This year saw the publication of two books on social psychology. The names of the books are An Introduction to Social Psychology by William McDougall and Social Psychology by sociologist Edward A. Ross.

Defining Social Psychology

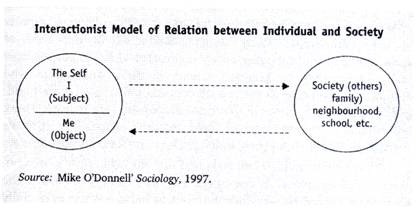

There is constant interaction between the intra-individual and social context and both influence each other mutually. Social psychology could be defined as the study of the “interface between these two sets of phenomena, the nature and cause of human social behaviour” (Michener & Delamater, 1999 cf. Delamater, 2006:11). G.W Allport (1954:5) defines social psychology with its emphasis on “the thought, feeling, and behaviour of individual as shaped by actual, imagined, or implied the presence of others”. A few other definitions of social psychology are as follows:

Social Psychology is the discipline that explores in an in-depth manner the various aspects of social interaction.

Baron and Byrne (2007) define social psychology as the scientific field that seeks to understand the nature and causes of individual behavior in social situations.

Importance of primary groups in sociology

Primary groups are important in several senses. They are equally important for individual as well as society. It is also equally important for child, youth and adults.

Because they prepare individuals to lead a successful social life. Primary group is the first group with which a child comes in contact at the prime stage of his life. It is the birth place of human nature. Primary group plays a very important role in the socialization process and exercises social control over them. With the help of primary group we learn and use culture. They perform a number of functions for individual as well as society which show their importance.

- Primary group shapes personality of individuals. It plays a very important role in molding, shaping and developing the personality of an individual. Because individual first come in contact with primary group. Individual is socialized in a primary group. It forms the social nature, ideas and ideals of individuals. His self develops in primary groups. A child learns social norms, standards, beliefs, morals, values, sacrifice, co-operation, sympathy and culture in a primary group.

- Primary group fulfills different psychological needs of an individual such as love, affection, fellow feeling, co-operation, companionship and exchange of thought. In primary group he lives among his near and dear ones. It plays an important role in the reduction of emotional stresses and mental tensions. Participation with primary groups provides a sense of belongingness to individuals. He considers himself as an important member of group.

- Individual lives a spontaneous living in a primary group. Spontaneity is more directly and clearly revealed in a primary group. Because of this spontaneous living members of a primary group come freely together in an informal manner. These informal groups satisfy the need for spontaneous living.

- Primary group provide a stimulus to each of its members in the pursuit of interest. The presence of others i.e. near and dear ones in a group acts as a stimulus to each. Here members get help, co-operation and inspiration from others. The interest is keenly appreciated and more ardently followed when it is shared by all the members. It is effectively pursued together.

- Primary group provides security to all its members. Particularly it provides security to the children, old and invalids. It also provides security to its members at the time of need. A member always feels a kind of emotional support and feels that there is someone on his side.

- Primary groups acts as an agency of social control. It exercises control over the behavior of its members and regulates their relations in an informal way. Hence there is no chance of individual member going astray. It teaches individuals to work according to the prescribed rules and regulations.

- Primary group develops democratic spirit within itself. It develops the quality of love, affection, sympathy, co-operation, mutual help and sacrifice, tolerance and equality among its members.

- Primary group introduces individuals to society. It teaches them how to lead a successful life in a society. It is the breeding ground of his mores and nurses his loyalties. K. Davis is right when he opines that “the primary group in the form of family initiates us into the secrets of society”. It helps the individual to internal social norms and learns culture.

- Primary group increases the efficiency of individuals by creating a favorable atmosphere of work. It provides them security and teaches many good qualities.

- Primary groups also fulfill different needs of society. It is the nucleus of all social organizations.

Georg Simmel viewed sociology as a distinct field focused on studying the patterns and forms of social interactions rather than just the structure of society itself. According to Simmel, the subject matter of sociology is the study of social forms—the recurring patterns, dynamics, and types of relationships that emerge in society. He was particularly interested in the interactional forms that shape social relationships, such as conflict, cooperation, subordination, and exchange.

Simmel believed sociology should investigate the essence of social relationships rather than solely focusing on specific institutions or roles. For instance, he examined how forms like dyads (two-person interactions) and triads (three-person groups) create different dynamics and complexities within relationships. By examining these interactions, Simmel sought to understand how individuality and social life coexist and influence each other.

Simmel also emphasized the role of urban life, culture, and social distance in shaping social interactions, which allowed him to explore how modern society affects human relationships. His work laid the foundation for understanding how social forms and individual experiences intersect, making sociology a discipline that reveals the patterns of human interaction across various social contexts.

The term “role” describes a set of expected actions and obligations a person has for his or her position in life and relationships with others. We all have multiple roles and responsibilities in our lives, from sons and daughters, sisters and brothers, mothers and fathers, spouses and partners to friends, and even professional and social ones.

The role not only provides a blueprint to guide the action, but also describes the goals to pursue, the tasks to perform, and the course of action for a particular scenario.

What is role conflict?

Role conflicts represent role-to-role conflicts that correspond to two or more statuses held by an individual. As we try to accommodate the many stats we hold, we experience role conflicts when we feel pulled in different directions.

The most obvious example of role conflict is the conflict between work and family, or the conflict felt when torn between family and work responsibilities. For example, consider a mother who is also a doctor. She is likely to have to work long hours in the hospital and may even call several nights a week to separate her children from her children. Many who have fallen into this situation say they are inconsistent and desperate about their situation. In other words, they experience role conflicts.

Why does role conflict occur?

Role conflicts occur when conflicting demands are placed on an individual in relation to work or position. People experience role conflicts when they feel that they are being pulled in different directions in an attempt to accommodate many of their stats. Role conflicts can be both short-term and long-term and can also be linked to contextual experiences.

There are two types of role conflict :

- Intra-role conflict

- Inter-role conflict

Intra-role conflicts

Conflicts within roles occur when the demand is in a single area of life, such as at the workplace. For example- two managers may ask an employee to complete a task, and both cannot be completed at the same time.

Inter-role conflicts

The conflict between individuals is due to differences in their goals and values. It refers to conflicting expectations from different roles within the same person. Inter-role conflicts are work-to-family conflicts that occur when work responsibilities clash with family obligations and family-to-work conflicts that occur when family responsibilities clash with work responsibilities.

Techniques to minimize conflicts

- Focus on what is said, not on how it is said.

- Do not formulate a response right away, first listen carefully.

- Clarify and reflect on what you are hearing.

- Don’t respond to high-intensity, emotional words.

- Monitor your non-verbal “leakage.”

- Recognize emerging needs and interests of another person.

- Excuse yourself for a “time-out” if emotions are escalated.

Socialization is essential in society as it is the process through which individuals learn the values, norms, and behaviors expected by their community. This foundational process begins in early childhood within the family and continues throughout life via schools, peer groups, media, and other social institutions. Socialization helps individuals internalize cultural beliefs, guiding them to function as contributing members of society.

Through socialization, people develop a sense of identity and learn their roles within social structures, such as being a student, parent, or employee. It fosters social cohesion by ensuring shared understandings and promoting mutual expectations that facilitate smooth interactions within society. Socialization also instills moral values and cultivates skills necessary for individuals to adapt to societal changes.

Moreover, socialization is crucial for maintaining social order as it encourages conformity to cultural norms and laws, reinforcing societal stability. By shaping individuals’ attitudes and behaviors, socialization enables the continuous transmission of cultural heritage and contributes to societal continuity, making it a vital element in the functioning of any society.

Social stratification refers to a society’s categorization of its people into groups based on socioeconomic factors like wealth, income, race, education, ethnicity, gender, occupation, social status, or derived power (social and political). It is a hierarchy within groups that ascribe them to different levels of privileges. As such, stratification is the relative social position of persons within a social group, category, geographic region, or social unit.

In modern Western societies, social stratification is defined in terms of three social classes: an upper class, a middle class, and a lower class; in turn, each class can be subdivided into an upper-stratum, a middle-stratum, and a lower stratum. Moreover, a social stratum can be formed upon the bases of kinship, clan, tribe, or caste, or all four.

The categorization of people by social stratum occurs most clearly in complex state-based, polycentric, or feudal societies, the latter being based upon socio-economic relations among classes of nobility and classes of peasants. Whether social stratification first appeared in hunter-gatherer, tribal, and band societies or whether it began with agriculture and large-scale means of social exchange remains a matter of debate in the social sciences. Determining the structures of social stratification arises from inequalities of status among persons, therefore, the degree of social inequality determines a person’s social stratum. Generally, the greater the social complexity of a society, the more social stratification exists, by way of social differentiation.

Stratification can yield various consequences. For instance, the stratification of neighborhoods based on spatial and racial factors can influence disparate access to mortgage credit.

Overview

Definition and usage

“Social stratification” is a concept used in the social sciences to describe the relative social position of persons in a given social group, category, geographical region or other social unit. It derives from the Latin strātum (plural ‘strata’; parallel, horizontal layers) referring to a given society’s categorization of its people into rankings of socioeconomic tiers based on factors like wealth, income, social status, occupation and power. In modern Western societies, stratification is often broadly classified into three major divisions of social class: upper class, middle class, and lower class. Each of these classes can be further subdivided into smaller classes (e.g. “upper middle”). Social strata may also be delineated on the basis of kinship ties or caste relations.

The concept of social stratification is often used and interpreted differently within specific theories. In sociology, for example, proponents of action theory have suggested that social stratification is commonly found in developed societies, wherein a dominance hierarchy may be necessary in order to maintain social order and provide a stable social structure. Conflict theories, such as Marxism, point to the inaccessibility of resources and lack of social mobility found in stratified societies. Many sociological theorists have criticized the fact that the working classes are often unlikely to advance socioeconomically while the wealthy tend to hold political power which they use to exploit the proletariat (laboring class). Talcott Parsons, an American sociologist, asserted that stability and social order are regulated, in part, by universal values. Such values are not identical with “consensus” but can indeed be an impetus for social conflict, as has been the case multiple times through history. Parsons never claimed that universal values, in and by themselves, “satisfied” the functional prerequisites of a society. Indeed, the constitution of society represents a much more complicated codification of emerging historical factors. Theorists such as Ralf Dahrendorf alternately note the tendency toward an enlarged middle-class in modern Western societies due to the necessity of an educated workforce in technological economies. Various social and political perspectives concerning globalization, such as dependency theory, suggest that these effects are due to changes in the status of workers to the third world.

Types of Social Stratification

The systems of social stratification do differ from one society to another, giving dimension to the alternative ways in which social hierarchies can be organized and held together. Generally, they determine a ranking of individuals and groups regarding wealth, power, and status. The types of social stratification explain how social inequalities have been structured and perpetuated in different contexts.

Caste System

Caste systems are a method of social stratification in society, where every individual is born into a particular social group or caste that defines the social status and profession of the individual for life. This system, prevalent in historical societies and those like India today, characteristically has absolute rigidity, with very little, if any, mobility across castes; it maintains rigid social boundaries. One’s caste generally governs the social role and interaction that individuals undertake with dim opportunities of changing one’s social position.

Class System

The class system refers to a more fluid form of economically-based social stratification with regard to wealth, income, and occupation. Similar to the caste system, though one can move from one group to another; this simply means that a class system is never rigid and always based on individual achievements, educational background, and economic success. It characterizes most modern industrialized societies where social status may be influenced by personal and economic factors in opposition to ascribed characteristics.

Estate System

The estate system is the historical type of social stratification predominantly prevailing in feudal society. It divides society into well-marked classes or estates, such as nobility, clergy, and commoners, with each estate having specifically defined rights and duties. Mobility is thus limited to one’s estate or class, with people usually staying within their estate or class, and social roles established by birth and land ownership rather than personal achievement.

Slavery

Slavery is a form of stratification wherein people are considered property and are made to labor without freedom in their person. The system defines the social status by the condition of being enslaved, and there is no possibility for mobility or betterment in status. Gross social inequalities and human rights violations that have severely affected the people concerned have been products of slavery’s history and modernity.

Kinship is the universal feature of human culture that served as the major organising principle in human societies. It can be defined as a principle by which individuals or groups of individuals are organised into social groups, roles, categories and genealogy by means of kinship terminologies. In Anthropology the study of kinship has existed ever since the mid-to-late 1800s, when LH Morgan and others invented the study of kinship. According to Robin Fox kinship is to anthropology what logic is to philosophy or the nude is to art; it is the basic discipline of the subject. The method central to the anthropological study of kinship is the comparative method – comparing similarities and differences of two cultures/societies.

Kinship has been defined by a number of anthropologist highlighting the role of biology and alliance in the formation of kin relation. Let us look at the some of the key definitions:

- Claude Levi Strauss- “Kinship and its related notions are at the same time prior and exterior to biological relations to which we tend to reduce them”.

- L.H. Morgan defines kin terms are, “reflected the forms of marriage and the related makeup of the family (system of consanguinity and affinity of woman family 1871).

- A.R. Radcliffe- Brown (1952) agreed that “Kinship terms are like signposts to interpersonal conducts or etiquette, with the implication of appropriate reciprocal right, duties privileges and obligations.

- MacLennan Writes that kinship terms are merely forms of solution and was not related to actual blood ties at all.

- J. Beattie, “Kinship is not set of genealogical relationships; it is set of social relationships”.

Culture is a term that refers to a large and diverse set of mostly intangible aspects of social life. According to sociologists, culture consists of the values, beliefs, systems of language, communication, and practices that people share in common and that can be used to define them as a collective.

Culture is a concept that encompasses the social behavior, institutions, and norms found in human societies, as well as the knowledge, beliefs, arts, laws, customs, capabilities, attitude, and habits of the individuals in these groups. Culture is often originated from or attributed to a specific region or location.

Humans acquire culture through the learning processes of enculturation and socialization, which is shown by the diversity of cultures across societies.

A cultural norm codifies acceptable conduct in society; it serves as a guideline for behavior, dress, language, and demeanor in a situation, which serves as a template for expectations in a social group. Accepting only a monoculture in a social group can bear risks, just as a single species can wither in the face of environmental change, for lack of functional responses to the change. Thus in military culture, valor is counted a typical behavior for an individual and duty, honor, and loyalty to the social group are counted as virtues or functional responses in the continuum of conflict. In the practice of religion, analogous attributes can be identified in a social group.

Cultural change, or repositioning, is the reconstruction of a cultural concept of a society. Cultures are internally affected by both forces encouraging change and forces resisting change. Cultures are externally affected via contact between societies.

Polygyny—the practice of a man having multiple wives—is influenced by a range of social, economic, and cultural factors across different societies. One major cause is economic advantage, particularly in agricultural societies, where more wives contribute to household labor, farming, and child-rearing, which can enhance family wealth and productivity.

Another cause is the imbalance in the male-to-female ratio, often due to factors like war, where men are fewer than women. Polygyny provides a means for all women to be economically and socially supported, particularly in communities where women’s livelihoods depend on male partnerships.

Cultural and religious practices also support polygyny in many societies, viewing it as a norm that aligns with traditional or spiritual beliefs. For example, some communities see polygyny as a way to preserve family lineage or expand social alliances by creating ties with multiple families.

High mortality rates among men and power dynamics in societies where men hold authority also contribute to polygyny, as influential men may take multiple wives to reinforce social or political power. Thus, polygyny often emerges as a response to economic, demographic, and cultural influences that shape family structures in various societies.

Acknowledging the impact of various forces stemming from the economic growth, Kapadia concludes that despite the clashes between different generations there is a strong feeling for the joint family in the generations that is coming up. He felt that the general assumption that joint family is dying out is invalid.

Eames points out that the projected disappearance of the joint family under the impact of urbanisation and industrialisation is more hypothetical than real. Milton Singer argues that certain aspects of modernisation may even strengthen the joint family.

Prof R K Mukherjee has falsified the causal and concomitant relation between what is considered as the traditional’ joint family and the ‘modern’ nuclear family approach because this approach is not valid even to the Western societies. Hence, the assumption that urbanisation and industrialization would lead to the nuclearisation of joint family in India is basically wrong.

In his paper Traditional Groups and Developmental process, Bryce Ryan has remarked that it is a functional necessity to have extended family and kinship system in an urban setting because they fulfill an important need of migrants. Urban living cannot completely dislodge the primordial ties of family, kinship, ethnicity or religion. He has emphasised the structural redefinition of the joint family relations in India which in effect, implies dissolution of traditional bonds. Hence, urbanisation may result in fanning out of kinsmen without losing their full significance.

However there are also other sociologists who hold different views about the future of joint ‘family system in India. A.D. Ross feels that if families living separately do not come into contact over long periods of time, feelings of family obligations and emotional attachment to family members will certainly weaken anfad the authority of the former patriarch will break down. When this happens, there will be little room left to maintain a feeling of and desire for identity within the larger kinship group.

G Kurian made certain specific observations after reviewing certain contemporary studies He envisaged increasing emphasis on small family units in the near future with more individuality of people and decreased dependence on the kin for survival.

It can be concluded that growing individuality and attraction for conjugal families will lead to the establishment of small family units. The famil.es may be called nuclear families although they do not represent the clear-cut norms of the nuclear family of the West There will be more and more independent families with decreased dependence on kin and without the attitude for fulfillment of obligation.

In American conjugal family system emphasis is laid on marital ties. In contrast to American conjugal family system a new type of conjugal family system is emerging in India which is likely to continue.

In these conjugal families emphasis is given on marital ties. At the same time husband and wife maintain strong relations with kins of female side. This may be due to fact that this provides a greater opportunity for wives to work independently and raise living standards without sharing the chores of a joint family.

Sociology is the science of social structure. It deals with the relationship of humans with society, their behaviour in social spaces, the changes in society brought by humans, and cultural influence in society.

In simple terms, Sociology is a part of the social sciences that tells us about human conduct and its functions and effects in society. The interaction between humans and society brings changes that affect everyone in multiple ways. The causes and consequences of human behaviour are the roots of sociology.

The main aspects of sociology include

- Emergence and transformation of society

- Human social behaviour

- Maintenance of social order

- Various social processes include cooperation, conflict, communication, biases.

What is economics?

Economics is a section of social sciences that interprets the availability of resources in society. It is a systematic and reasoned way of studying the pattern of demand and usage of resources and their lack in society.

Economics deals with the wants, needs, and demands of resources and their supply and fulfilment at the individual level and in society. The study of the consumption pattern helps determine various aspects of society, such as inflation and wealth management. It also makes predictions about changes in demand and supply of resources in the future.

The main aspects of economics include:

- Wants and needs of resources

- Consumption of resources

- Production of resources

- Wealth distribution

What is economic sociology?

Economic sociology analyses economic events like inflation, market, and work using sociological philosophy and theory. It is a subdivision of sociology that studies the working of the society looking from a sociological perspective.

What is the significance of sociology in economics?

Studying the pattern of societal changes helps determine various aspects of the economy, including gender equality, education, immigration and emigration, environmental issues, framing economic welfare schemes and programs, etc. Moreover, studying these aspects of society helps find out the solutions to challenges faced by society.

The difference between sociology and economics

The main differences between sociology and economics are discussed below.

Sociology | Economics |

Sociology has comparatively emerged in recent times. | Economics is an age-old institution used to deal with the changing patterns in society. |

Sociology deals with the relationship between humans and society. | Economics helps understand the pattern of want and consumption of resources. |

The focus of study in sociology is society and the behaviour of humans in society. Sociology takes a conceptual and philosophical view of society. It is an abstract science of society. | The focus of study in economics is individual humans. The unlimited want of resources and the supply of them is the basis. Economics uses systematic and logical analysis of society. It is a concrete science of society. |

The scope of sociology has a broader range since it involves various aspects of society. | The scope of economics is comparatively limited since it deals with the availability of resources and their consumption. |

Sociology involves the activities of individuals in a society. | Economics involves the economic activities of individuals and society, taken individually and as a whole. |

What is the relationship between sociology and economics?

The welfare and wellbeing of society come with economic prosperity. If the economy is flourishing, then it will bring harmony to society. On the other hand, if the economy faces a crisis, it will severely impact society. For example, inflation, poverty, and unemployment severely affect the health and wellbeing of individuals and society as a whole.

Sociology is also dependent on economics in various ways. Any event that happens in society is directly or indirectly influenced by economics. Every social problem has its cause in some aspect of the economy. Whether it’s the case of social evils like domestic violence or preference for male children, it all has its origin in economics.

Analysing several social changes and problems in society requires economics to understand the patterns and find solutions. With the knowledge and research of society, economics plays a crucial role in every aspect.

The relationship between sociology and economics is a complex yet close one. Without economics, there is no basis for sociology. And without sociology, economics would not make sense.

The close association between sociology and economics makes it possible to analyse and solve complex sociological and economic development problems.

The secondary groups are just opposite of primary groups. What makes the relationship secondary is the relatively narrow, utilitarian, task-oriented, time-limited focus of its activities. A secondary group is organised around secondary relationships. These relationships are more formal, impersonal, segmental and utilitarian than primary group interactions.

Formal organisations and larger instrumental associations such as trade associations, labour unions, corporations, political parties, international cartel, a club and many others are a few examples of secondary groups. In such groups, one is not concerned with the other person as a person, but as a functionary who is filling a role.

In the secondary group not total personality but a segmental (partial) personality of a person is involved. These groups are wholly lacking in intimacy of association as we generally find in primary groups. Defining these groups, Ogburn and Nimkoff (1950) write: “The groups which provide experience lacking in intimacy are called secondary groups.” Kimball Young (1942) has termed these groups as ‘special interest groups’ because they are formed to fulfill certain specific end or ends.

Features

Large Size

Secondary groups are large in size. They comprise of a large number of members and these members may spread all over the world. For example, the Red Cross Society, it’s members scattered all over the world. Because of this large size indirect relations found among the members.

Definite Aims

Secondary groups are formed to fulfill some definite’ aims. The success of a secondary group is judged according to the extent by which it became able to fulfil those aims. A school, college or university is opened to provide education.

Voluntary Membership

The membership of a secondary group is voluntary in nature. Whether one will be a member of a secondary group or not it depends on his own volition. No one can compel him to be a member of any secondary group. It is not essential that one should be a member of a particular political party.

Formal, Indirect and Impersonal Relation

The relations among the members of a secondary group are indirect, formal and impersonal type. People do not develop personal relations among themselves. Relations in a secondary group are not face-to- face rather touch and go type and casual. They interact among themselves in accordance with formal rules and regulations. Because of large size it is not possible to establish direct relations among themselves; one is not directly concerned with the other aspects of his fellow’s life. Contact and relation among member are mainly indirect.

Active and Inactive Members

In a secondary group we found both active as well as inactive members. Some members became more active while others remain inactive. This is due to the absence of intimate and personal relations among the members. For example in a political party some members do not take active interest while some others take active interest in party work.

Formal Rules

A secondary group is characterized by formal or written rules. These formal rules and regulations exercises control over its members. A secondary group is organised and regulated by formal rules and regulations. A formal authority is set up and a clear cut division of labor is made. He who do not obey these formal rules and regulations losses his membership.

Status of an individual depends on his role

It is another important characteristic of a secondary group. Because in a secondary group the status and position of each and every member depends on his role that he plays in the group. Birth or Personal qualities do not decide one’s status in a secondary group.

Individuality in Person

Secondary group is popularly known as ‘special interest groups’. Because people became member of secondary group to fulfill their self-interest. Hence they always give stress on the fulfillment of their self-interests. After fulfillment of these interests they are no longer interested in the group. As a result in secondary group individuality in person is found.

Self-dependence among Members

Self-dependency among members is another important characteristic of a secondary group. Because of the large size of the secondary group the relations among the members are indirect and impersonal. Members are also selfish. As a result each member tries to safeguard and fulfill his own interest by himself

Dissimilar Ends

Secondary group is characterized by dissimilar ends. The members of a secondary group have different and diverse ends. To fulfill their diverse ends people join in a secondary group.

Relationship is a means to an end

Secondary relations are not an end in itself rather it is a means to an end. Establishment of relationship is not an end rather individual establish relationship to fulfill his self interest. They became friends for specific purposes.

Formal Social Control

A secondary group exercises control over its members in formal ways such as police, court, army etc. Formal means of social control plays an important role in a secondary group.

Division of Labor

A secondary group is characterized by division of labor. The duties, functions and responsibilities of members are clearly defined. Each member has to perform his allotted functions.

The origin of sociology and social anthropology in India can be traced to the days when the British officials realized the need to understand the native society and its culture in the interest of smooth administration. However, it was only during the twenties of the last century that steps were taken to introduce sociology and social anthropology as academic disciplines in Indian universities.

The popularity that these subjects enjoy today and their professionalization is, however, a post-independence phenomenon. Attempts have been made by scholars from time to time to outline the historical developments, to highlight the salient trends and to identify the crucial problems of these subjects.

Sociology and social/cultural anthropology are cognate disciplines and are in fact indissoluble. However, the two disciplines have existed and functioned in a compartmentalized manner in the European continent as well as in the United States. This separation bears the indelible impress of western colonialism and Euro-centrism.

However, Indian sociologists and anthropologists have made an attempt to integrate sociology and anthropology in research, teaching and recruitment. They have made a prominent contribution to the development of indigenous studies of Indian society and have set an enviable example before the Asian and African scholars.

Another significant contribution of Indian sociology and social/cultural anthropology lies in their endeavor to synthesize the text and the context. This synthesis between the text and the context has provided valuable insights into the dialectic of continuity and change to contemporary Indian society (Momin, 1997).

It is difficult to understand the origin and development of sociology in India without reference to its colonial history. By the second half of the 19th century, the colonial state in India was about to undergo several major transformations.

Land, and the revenue and authority that accrued from the relationship between it and the state, had been fundamental to the formation of the early colonial state, eclipsing the formation of Company rule in that combination of formal and private trade that itself marked the formidable state-like functions of the country.

The important event that took place was the revolt of 1857, which showed that the British did not have any idea about folkways and customs of the large masses of people. If they had knowledge about Indian society, the rebellion of 1857 would not have taken place. This meant that a new science had to come to understand the roots of Indian society. The aftermath of 1857 gave rise to ethnographic studies. It was with the rise of ethnography, anthropology and sociology which began to provide empirical data of the colonial rule.

Herbert Risley was the pioneer of ethnographic studies in India. He entered the Indian Civil Services in 1857 with a posting in Bengal. It was in his book Caste and Tribes of Bengal (1891) that Risley discussed Brahminical sociology, talked about ethnography of the castes along with others that the importance of caste was brought to colonial rulers. Nicholas Dirks {In Post Colonial Passages, Sourabh Dube, Oxford, 2004) observes:

Risley’s final ethnographic contribution to colonial knowledge thus ritualed the divineness of caste, as well as its fundamental compatibility with politics only in the two registers of ancient Indian monarchy or modern Britain’s ‘benevolent despotism’.

Thus, the ethnographic studies came into prominence under the influence of Risley. He argued that to rule India caste should be discouraged. This whole period of 19th century gave rise to ethnographic studies, i.e., studies of caste, religion, rituals, customs, which provided a foundation to colonial rule for establishing dominance over India. It is in this context that the development of sociology in India has to be analysed.

Sociology and social anthropology developed in India in the colonial interests and intellectual curiosity of the western scholars on the one hand, and the reactions of the Indian scholars on the other. British administrators had to acquire the knowledge of customs, manners and institutions of their subjects.

Christian missionaries were interested in understanding local languages, folklore and culture to carry out their activities. These overlapping interests led to a series of tribal, caste, village and religious community studies and ethnological and linguistic surveys. Another source of interest in Indian studies was more intellectual.

While some western scholars were attracted by the Sanskrit language, Vedic and Aryan civilization, others were attracted by the nature of its ancient political economy, law and religion. Beginning from William Jones, Max Muller and others, there was a growth of Indo logical studies. Karl Marx and Frederic Engels were attracted by the nature of oriental disposition in India to build their theory of evolution of capitalism.

Similarly, Henry Maine was interested in the Hindu legal system and village communities to formulate the theory of status to contract. Again, Max Weber got interested in Hinduism and other oriental religions in the context of developing the theory, namely, the spirit of capitalism and the principle of rationality developed only in the West.

Thus, Indian society and culture became the testing ground of various theories, and a field to study such problems as growth of town, poverty, religion, land tenure, village social organization and other native social institutions. All these diverse interests – academic, missionary, administrative and political – are reflected in teaching of sociology.

According to Srinivas and Panini (1973: 181), the growth of the two disciplines in India falls into three phases:

The first, covering the period between 1773-1900 AD, when their foundations were laid;

The second, 1901-1950 AD, when they become professionalized;

and finally, the post-independence years, when a complex of forces, including the undertaking of planned development by the government, the increased exposure of Indian scholars to the work of their foreign colleagues, and the availability of funds, resulted in considerable research activity.

Here, three major phases in the introspection in sociology, which have been discussed by Rege (1997) in her thematic paper on ‘Sociology in Post-Independent India’, may also be mentioned. Phase one is characterized by the interrogations of the colonial impact on the discipline and nationalist responses to the same, phase second is marked by explorations into the initiative nature of the theoretical paradigms of the discipline and debates on strategies of indigenization.

This phase also saw critical reflections on the deductive positivistic base of sociology and the need for Marxist paradigms and the more recent phase of post-structuralism, feminist and post-modern explorations of the discipline and the field. Lakshmanna also (1974: 1) tries to trace the development of sociology in three distinctive phases. The first phase corresponds to the period 1917-1946, while the second and the third to 1947-1966 and 1967 onwards respectively.

Sociology in the Pre-Independence Period

As is clear by now that sociology had its formal beginning in 1917 at Calcutta University owing to the active interest and efforts of B.N. Seal. Later on, the subject was handled by Radhakamal Mukerjee and B.N. Sarkar. However, sociology could not make any headway in its birthplace at Calcutta.

On the other hand, anthropology flourished in Calcutta with the establishment of a department and later on the Anthropological Survey of India (ASI). Thus, sociology drew a blank in the eastern parts of the country. But, the story had been different in Bombay. Bombay University started teaching of sociology by a grant of Government of India in 1914.

The Department of Sociology was established in 1919 with Patrick Geddes at the helm of affair. He was joined by G.S. Ghurye and N.A. Toothi. This was indeed a concrete step in the growth of sociology in India. Another centre of influence in sociological theory and research was at Lucknow that it introduced sociology in the Department of Economics and Sociology in 1921 with Radhakamal Mukerjee as its head.

Later, he was ably assisted by D.P. Mukerji and D.N. Majumdar. In South India, sociology made its appearance at Mysore University by the efforts of B.N. Seal and A.F. Wadia in 1928. In the same year sociology was introduced in Osmania University at the undergraduate level. Jafar Hasan joined the department after he completed his training in Germany.

Another university that started teaching of sociology and social anthropology before 1947 was Poona in the late 1930s with Irawati Karve as the head. Between 1917 and 1946, the development of the discipline was uneven and in any case not very encouraging. During this period, Bombay alone was the main centre of activity in sociology. Bombay attempted a synthesis between the Indo-logical and ethnological trends and thus initiated a distinctive line of departments.

During this period, Bombay produced many scholars who richly contributed to the promotion of sociological studies and research in the country. K.M. Kapadia, Irawati Karve, S.V. Karandikar, M.N. Srinivas, A.R. Desai, I.P. Desai, M.S. Gore and Y.B. Damle are some of the outstanding scholars who shaped the destiny of the discipline. The products of this university slowly diffused during this period in the hinterland universities and helped in the establishment of the departments of sociology.

Certain trends of development of sociology may be identified in the pre-independence period. Sociology was taught along with economics, both in Bombay and Lucknow. However, in Calcutta, it was taught along with anthropology, and in Mysore it was part of social philosophy.

Teachers had freedom to design the course according to their interests. No rigid distinction was made between sociology on the one hand and social psychology, social philosophy, social anthropology, social work, and other social sciences such as economics and history, on the other. The courses included such topics as social biology, social problems (such as crime, prostitution and beggary), social psychology, civilization and pre-history. They covered tribal, rural and urban situations.

At the general theoretical level, one could discern the influence of the British social anthropological traditions with emphasis on diffusionism and functionalism. In the case of teaching of Indian social institutions the orientation showed more Indo-logical emphasis on the one hand and a concern for the social pathological problems and ethnological description on the other. Strong scientific empirical traditions had not emerged before independence. Sociology was considered a mixed bag without a proper identity of its own.

Sociology in the Post-Independence Period

The next phase, as mentioned by Lakshmanna (1974: 45), in the growth of the subject, corresponds to the period between the attainment of independence and the acceptance of the regional language as the medium of instruction in most states of the country. Towards the end of this period, we also witnessed the interest on the part of the Central Government to promote social science research through a formal organization established for the purpose.

This phase alone experienced tremendous amount of interaction within the profession as two parallel organizations started functioning for the promotion of the profession. In Bombay, Indian Sociological Society was established and Sociological Bulletin was issued as the official organ of the society. This helped to a large extent in creating a forum for publication of sociological literature.

Lucknow school, on the other hand, started the All India Annual Sociological Conference for professional interaction. Lakshmanna identifies that the research efforts mainly progress on three lines. First, there was large-scale doctoral research in the university. Second, the growing needs of the planners and administrators on the one hand and the realization of increasing importance of sociological thinking and research in the planning process on the other, opened up opportunities for research projects.