Ancient History – 3rd Year

Paper – III (PYQs Soln.)

Unit I

Language/भाषा

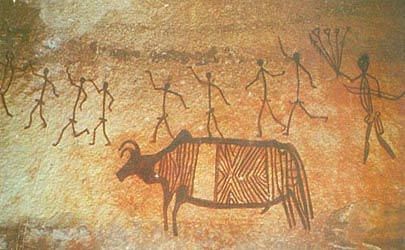

Prehistoric paintings were usually painted on rocks, and these rock carvings were referred to as Petroglyphs. The first prehistoric paintings were uncovered in Madhya Pradesh’s Bhimbetka caves. Paintings and sketches were the earliest art forms used by humans to express themselves on a cave wall as a canvas.

Historical Background

- Seven historical periods may be identified in the sketches and paintings.

- V.S.Wakankar, an archaeologist, discovered the Bhimbetaka paintings in 1957-58.

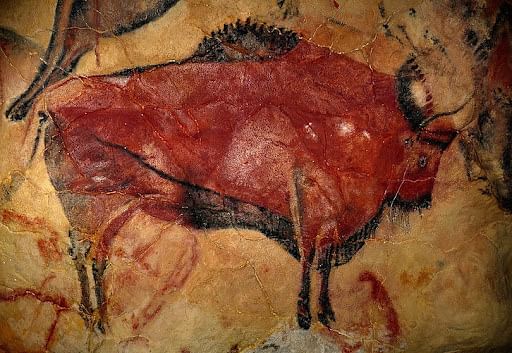

- These paintings typically depict animals such as bison, beers, and tigers. They are known as the ‘Zoo Rock Shelter’ because they depict elephants, rhinoceroses, cattle, snakes, spotted deer, barasingha, and other animals.

- Prehistoric paintings can be divided into three major phases:

- Palaeolithic Period

- Mesolithic Period

- Chalcolithic Period

Pre-historic Art

Upper Palaeolithic Period (40000–10000 BC)

- Since the walls of the rock shelter caves were formed of quartzite, minerals were employed as paints.

- Ochre or geru, when mixed with lime and water, was one of the most frequent minerals.

- They broadened their palette by using other minerals to create colours like red, white, yellow, and green.

- Large animals such as bison, elephants, rhinos, tigers, and others were shown in white, dark red, and green.

- Red was utilised for hunters and green was used largely for dancers in human sculptures.

- Remains of rock paintings have been discovered on the walls of caves in Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Karnataka, Bihar, and Uttarakhand in India.

- Lakhudiyar in Uttarakhand, Kupgallu in Telangana, Piklihal and Tekkalkotta in Karnataka, Bhimbetka and Jogimara in Madhya Pradesh, and others are examples of early rock painting locations.

- Man, Animal, and Geometric Symbols are the three categories of paintings featured here.

Features of these early works of art

- Humans are depicted as a stick-like figure.

- In the early paintings, a long-snouted animal, a fox, and a multi-legged lizard are common animal motifs (later many animals were drawn).

- There are additional wavy lines, rectangular-filled geometric shapes, and a group of dots.

- Paintings are superimposed one on top of the other, starting with black, then red, and finally white.

- Bhimbetka is one of India’s and the world’s oldest paintings (Upper paleolithic).

Upper Palaeolithic Period Art

Mesolithic Period (10000–4000 BC)

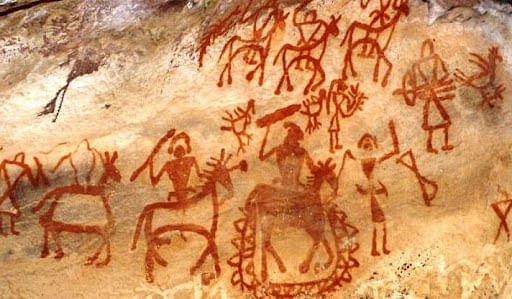

- This is the period with the greatest amount of artwork. Themes are numerous, yet the paintings are modest.

- The majority of the scenes are of hunters. Hunters wielded barbed spears, pointed sticks, arrows, and bows in groups.

- Some paintings depict traps and snares used to catch animals.

- Animal pointing was a popular pastime among Mesolithic people. Animals are chasing men in some photographs, while hunters are chasing them in others.

- The colour red was heavily used throughout this time period.

- The scale of the paintings shrank throughout this period in comparison to the Upper Paleolithic epoch.

- Group hunting is one of the most common scenarios represented in these paintings, and several others depict grazing and riding activities.

Chalcolithic Period

- The number of paintings employing the colors green and yellow increased throughout this time period.

- The majority of the paintings are depictions of battle scenes. Many paintings depict men riding elephants and horses.

- Some of them even have bows and arrows, indicating that they are ready for conflicts.

- They feature drawings of spotted deer skins drying, which supports the hypothesis that man perfected the art of tanning skins for shelter and clothing.

- Musical instruments such as the harp are also depicted in other artworks from this time period.

- Complex geometrical shapes such as the spiral, rhomboid, and circle appear in several of the paintings.

- The Jogimara caves in the Ramgarh hills in the Surguja district of Chhattisgarh include some paintings from the later period. These are thought to have been painted about the year 1000 BCE.

- In the Kanker area of Chhattisgarh, caves such as the refuge of Udkuda, Garagodi, Khaperkheda, Gotitola, Kulgaon, and others may be found.

- Human figurines, animals, palm prints, bullock carts, and other depictions of a higher and sedentary way of life can be found in these shelters.

- Similar paintings may be found in the Koriya district’s Ghodasar and Kohabaur rock art sites.

- Another intriguing location is Chitwa Dongri (Durg district), where we can see a Chinese figure riding a donkey, as well as dragon paintings and agricultural scenes.

Chalcolithic Period Art

Significance of Prehistoric Paintings

- White, yellow, orange, red ochre, purple, brown, green, and black were among the colours used.

- However, their favorite colors were white and red. These folks manufactured their paints by crushing a variety of colored pebbles. Haematite turned them red (Geru in India).

- Chalcedony, a green-coloured rock, was used to make this green. Limestone was most likely the source of white.

- When mixing rock powder with water, sticky substances such as animal fat, gum, or tree resin may be employed. Plant fiber brushes were used.

- The chemical reaction of the oxide existing on the surface of rocks is thought to have kept these colours for thousands of years.

- Paintings have been discovered in both occupied and vacant caves.

- It suggests that these artworks were occasionally utilized as signals, warnings, and other similar purposes.

- Many of the new rock art sites have been painted over an older painting. Nearly 20 layers of paintings are visible at Bhimbetka, one on top of the other.

- It depicts the human being’s progressive evolution from one period to the next. Nature’s inspiration is combined with a hint of mysticism in symbology.

- Only a few drawings are used to express ideas (representation of men by the stick-like drawings). Many geometrical patterns are used.

- The majority of the scenes depicted hunting, as well as people’s economic and social lives. Flora, fauna, humans, legendary creatures, carts, chariots, and other figures can be observed.

- The colours red and white are more important.

Conclusion

The Prehistoric period is defined as a time in the far past when there was no paper, language, or written word, and hence no books or written documents. Until scholars began excavating Prehistoric sites, it was difficult to comprehend how Prehistoric people lived. Scholars have pieced together information gleaned from old artefacts, environment, animal and human bones, and artwork on cave walls to create a pretty accurate picture of what happened and how people lived in prehistoric periods.

The Harappan civilization’s town layout supports the idea that the city’s municipal establishments were well developed. The Indus Valley civilization is distinguished by its town layout. Their town layout demonstrates that they had a civilised and evolved life. In nature, town planning was fantastic. A few towns feature citadels to the west built on higher platforms, with residential areas to the east. They are both enclosed by a large masonry wall. Cities without a fortress are built on towering mounds.

Town Planning & Structures

- The Harappan civilisation was characterised by its grid-based town planning system, in which streets and alleys cut across one another virtually at right angles, separating the city into many rectangular blocks.

- Harappa, Mohenjodaro, and Kalibangan each had their own castle erected on a high mud-brick pedestal.

- Each city has a lower town with brick buildings occupied by the ordinary people beneath the castle.

- The Harappan civilisation is distinguished by the widespread use of burned bricks in practically all types of architecture and the lack of stone structures.

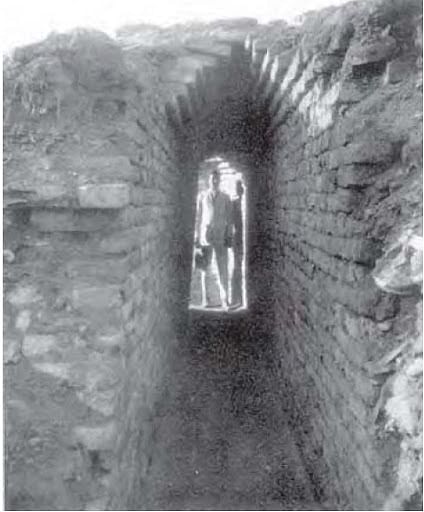

- Another notable feature was the underground drainage system that connected all dwellings to street drains that were covered by stone slabs or bricks.

- The Great Bath, which is 39 feet long, 23 feet wide, and 8 feet deep, is Mohenjodaro’s most significant public space.

- A flight of steps leads to the surface at each end. There are separate dressing rooms. The Bath’s floor was constructed of charred bricks.

- The biggest structure at Mohenjodaro is a granary 150 feet long and 50 feet wide.

- However, there are as many as six granaries in Harappa’s fortress.

Features

Streets and Roads

- Indus Valley’s streets and roadways were all straight and intersected at a right angle.

- All of the roadways were constructed with burned bricks, with the length of each brick being four times its height and the breadth being two times its height.

- They ranged in width from 13 to 34 feet and were fully lined.

- The city was split into rectangular blocks by the streets and roadways.

- Archaeologists unearthed the lamp posts at regular intervals. This implies the presence of street lighting.

- On the streets, there were also trash cans. These demonstrate the presence of competent municipal management.

Streets of Indus Valley Civilization

Drainage system

- One of the most notable elements of the Indus Valley civilization was the city’s efficient closed drainage system.

- Cities of the Indus Valley Civilization possessed sophisticated water and sewage systems.

- Many Indus Valley sites have houses with single, double, and more rooms coupled to a very effective drainage system.

- Each residence had its own drainage and soak pit that was linked to the public drainage system.

- Every roadway was lined by brick-paved canals.

- They were covered and had manholes at regular intervals for cleaning and clearing.

- To convey extra water, large brick culverts with corbelled roofs were built on the city’s outskirts.

- As a result, the Indus people developed a flawless subsurface drainage system.

- No other modern culture paid such close attention to hygiene.

- Corbelled drains were the primary method of collecting waste and rainfall; they may also have been used to empty enormous pools used for ceremonial washing.

A drain in Mohenjodaro

Great bath

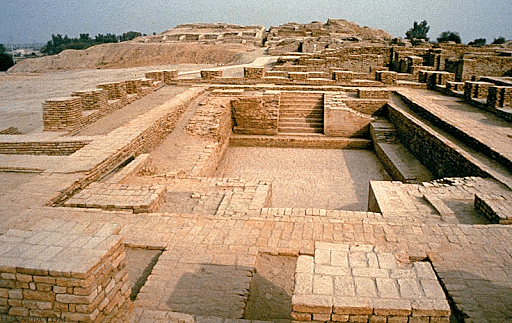

- The Great Bath is the most notable feature of Mohenjodaro. It is made up of a big quadrangle.

- The discovery reveals that the Great Bath, which was located within the city, was a huge rectangular tank used for special rites or ceremonial bathing and resembled a modern-day swimming pool.

- There is a large swimming pool in the centre (about 39 feet long, 23 feet wide, and 8 feet deep) with the ruins of galleries and chambers on all four sides.

- It features a flight of stairs at either end and is supplied by a well in one of the neighbouring apartments.

- The water was released through a massive drain with a corbelled ceiling that was more than 6 feet deep.

- The Great Bath’s outside walls were 8 feet thick.

- To prevent water leakage, the tank was covered with gypsum.

- For 5000 years, this sturdy structure has resisted the assaults of nature.

- Some rooms were equipped with hot water baths.

The Great Bath source

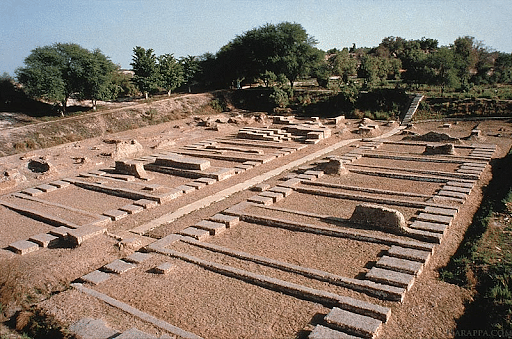

Granaries

- The granary, which is 45.71 metres long and 15.23 metres broad, is the biggest structure at Mohenjodaro.

- Harappa has a set of brick platforms that served as the foundation for two rows of six granaries each.

- Brick platforms have also been discovered in the southern section of Kalibangan.

- These granaries protected the grains, which were most likely gathered as income or as storehouses to be used in crises.

- During disasters, most staple foods like rice, wheat, and barley were stockpiled in these warehouses for public distribution.

- The cervical granaries were a massive building.

- Archeological evidence suggests that the lowest half of the stockroom was formed of blocks, while the upper part was most likely made of wood.

Granaries of Harappan Civilization

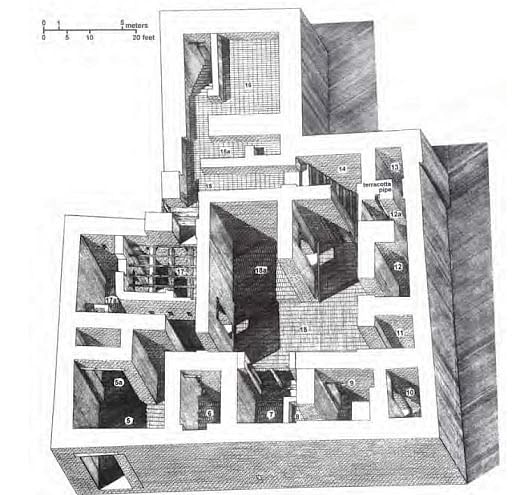

Buildings

- People from the Indus Valley civilisation erected dwellings and other structures beside highways.

- They constructed terraced dwellings out of charred bricks. Every dwelling had at least two rooms.

- There were also multi-story buildings.

- The buildings were built around an inner courtyard and had pillared hallways, bath rooms, paved floors, a kitchen, a well, and other amenities.

- In addition to living quarters, extensive constructions have been discovered.

- One of these structures has the largest hall, which is 80 feet long and 80 feet broad.

- It might have been a castle, a temple, or a meeting hall.

- There are also workmen’s quarters. It had an outstanding water supply system. There were public wells throughout the streets.

- Each large residence has its own well.

- They also constructed a dockyard at Lothal.

- The majority of the residences in the Lower Town featured a central courtyard surrounded by rooms.

- Summer activities like cooking and knitting were most likely done in the courtyard.

- To promote privacy, the main entrance was usually located so that it did not provide a direct view of the inside.

- Furthermore, there were no windows on the ground-level walls of the dwellings.

An isometric drawing of a large house in Mohenjodaro

Conclusion

The Indus Valley Civilization was one of the world’s oldest and most advanced civilizations. The cities were well-planned and developed. Waste collection and disposal were also done in a lovely way, as a wooden screen was put at the end of the main sewer, demonstrating that they were also concerned about water contamination. Streets were also built in an engineering manner, using burnt bricks and a well-drained system.

Sculptures of the Harappan Civilization hold a significant role in understanding the lifestyle of the Harappan people. It also helps historians to understand the civilization further.

Sculptures of the Harappan Civilization

- During the second millennium, the arts of the Indus Valley civilization, one of the world’s first civilizations, arose. Sculptures, seals, ceramics, gold jewelry, terracotta figurines, and other types of art have been discovered at many civilization sites.

- Their renderings of human and animal forms were extremely lifelike and the modeling of figures was done with utmost caution.

- The major materials used for sculptors were: Stone, Bronze, Terracotta, Clay, etc.

Stone Sculptures of Harappan Civilization

The handling of the 3-Dimensional volume may be seen in stone figures found in Indus valley sites. There are two major stone statues:

- In Mohenjo-Daro, a Bearded Man (Priest Man, Priest-King) was discovered. The main features of the figure were:

- Steatite figurine of a bearded guy.

- The figure is covered in a shawl that comes under the right arm and covers the left shoulder, indicating that it is a priest. The shawl has a trefoil design on it.

- As in contemplative concentration, the eyes are extended and partially closed.

- The nose is well-formed and of average size.

- Short beard and whiskers, as well as a short moustache.

- A basic woven fillet is carried around the head once the hair is separated in the center.

- A right-hand armlet and holes around the neck imply a necklace.

- Overall, there is a hint of the Greek style in the statues.

Bearded Priest

- Male Torso

- Red sandstone was used to create it.

- The head and arms are attached to the neck and shoulders through socket openings. Legs have been broken.

- The shoulders are nicely browned, and the belly is a little protruding.

- It is one of the more expertly cut and polished pieces.

Bronze Sculptures of Harappan Civilization

- Bronze casting was conducted on a large scale in practically all of the civilization’s main sites.

- Bronze casting was done using the Lost Wax Technique.

Lost Wax Technique

- At first, the required figure is formed of wax and coated with clay. After allowing the clay to dry, the entire assembly is heated to melt the wax within the clay. The melted wax was then drained out of the clay section through a small hole.

- The molten metal was then poured into the hollow clay mold. The clay coating was fully removed once it had cooled.

- The Bronze casting includes both human and animal representations.

- The buffalo, with its raised head, back, and sweeping horns, and the goat, among animal representations, are aesthetic assets.

- Bronze casting was popular at all locations of Indus valley culture, as evidenced by the copper dog and bird of Lothal and the Bronze figure of a bull from Kalibangan.

- Metal casting persisted until the late Harappan, Chalcolithic, and other peoples following the Indus valley civilization.

Examples of Bronze Casting are:

Dancing Girl

- Founded in Mohenjo-Daro, is one of the best-known artifacts from Indus valley.

- It depicts a girl whose long hair is tied in a bun and bangles cover her left arm.

- Cowry shell necklace is seen around her neck with her right hand on her hip and her left hand clasped in a traditional Indian dance gesture.

Dancing Girl

Bull from Mohenjo-Daro

- Mohenjo-Daro has a bronze statue of a bull.

- The bull’s massiveness and the charge’s wrath are vividly depicted.

- The animal is seen standing to the right with his head cocked.

- A cord is wrapped around the neck.

Terracotta Sculptures of Harappan Civilization

- In Gujarat and Kalibangan, terracotta statues are more lifelike.

- A few figures of bearded males with coiled hairs are found in terracotta, their stance firmly erect, legs slightly apart, and arms parallel to the sides of the torso. The fact that this figure appears in the same posture over and over again suggests that he was a divinity.

- There was also a clay mask of a horned god discovered.

- Terracotta was also used to create toy carts with wheels, whistles, rattles, birds and animals, gamesmen, and discs.

- Mother Goddess figurines are the most important clay figures.

The main example of a terracotta figure is:

Mother Goddess

- Mohenjo-Daro is where it was found.

- These are mainly crude standing figurines.

- Wearing a loin robe and a grid, she is adorned with jewelry dangling from her large breast.

- The mother goddess’s distinctive ornamental element is her fan-shaped headpiece with a cup-like protrusion on either side.

Mother Goddess

- The figure’s pellet eyes and beaked snout are exceedingly primitive (constructed in a rudimentary way).

- A tiny hole indicates the mouth.

Conclusion

The artists and craftsmen of the Indus Valley were extremely skilled in a variety of crafts—metal casting, stone carving, making and painting pottery, and making terracotta images using simplified motifs of animals, plants, and birds, making the civilization a rich one.

Indian art represents one of the richest, most diverse, and continuously evolving traditions in world history. Spanning thousands of years, it reflects the subcontinent’s multifaceted cultural, religious, and historical influences, from the ancient civilizations of the Indus Valley to the globalized contemporary era. Indian art is characterized by its symbolism, spiritual essence, and the harmonious blending of indigenous traditions with foreign influences. Its development is intricately linked with the region’s social, political, and religious transformations, making it a profound medium of expression that transcends mere aesthetic appeal.

Spirituality and Religious Themes

One of the defining features of Indian art is its profound connection to spirituality and religion. The art forms often serve as mediums to express devotion and convey philosophical ideas rooted in Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, and later Islam and Christianity. The emphasis on iconography is notable, with detailed depictions of deities, mythological narratives, and cosmic symbols.

The murti (idol) tradition in Hinduism exemplifies the anthropomorphic and symbolic representation of gods and goddesses, such as Shiva as Nataraja, the cosmic dancer, and Vishnu reclining on Shesha, the serpent. Similarly, Buddhist art is replete with images of the Buddha and Bodhisattvas, which reflect an emphasis on enlightenment and compassion. Thinkers like Ananda Coomaraswamy, a pioneer in the study of Indian art, emphasized the spiritual dimension, describing Indian art as a “visual scripture” that conveys eternal truths.

Symbolism and Abstraction

Indian art often employs symbolism and abstraction to represent complex ideas. For instance, the lotus flower symbolizes purity and spiritual awakening, while mandalas represent the cosmos in Buddhist and Hindu traditions. The yaksha and yakshi figures, seen in ancient sculpture, embody fertility and abundance. These symbols transcend the physical world, offering a deeper, philosophical understanding of the universe.

Continuity and Tradition

Another remarkable feature of Indian art is its continuity over millennia. Despite changes in political regimes and cultural influences, Indian art retained its core principles while adapting to new ideas. For example, the terracotta figurines and seals of the Indus Valley Civilization (2500–1500 BCE), with their stylized forms and intricate designs, set the foundation for later artistic traditions. The continuity is evident in the use of motifs like the bull and the tree of life, which appear in later Hindu, Buddhist, and Jain art.

The evolution of temple architecture also reflects this continuity. The Nagara style of North India and the Dravida style of South India developed distinct characteristics while adhering to shared principles outlined in texts like the Shilpa Shastras, ancient treatises on art and architecture.

Diversity of Regional Styles

Indian art is extraordinarily diverse, reflecting the subcontinent’s geographical, cultural, and linguistic variety. Each region developed its own distinct artistic styles and traditions, influenced by local materials, patronage, and cultural interactions.

For instance, the Pahari paintings of the Himalayan region are known for their lyrical depictions of Krishna’s life, while the Madhubani art of Bihar employs vibrant, geometric patterns to portray scenes from Hindu epics. The Tanjore paintings of Tamil Nadu, with their use of gold leaf and intricate detailing, showcase the grandeur of South Indian devotional art. This regional diversity highlights the adaptability and inclusivity of Indian art traditions.

Integration of Foreign Influences

Indian art is also notable for its ability to assimilate and transform foreign influences. The arrival of Hellenistic art during the Mauryan and Kushana periods led to the development of the Gandhara school, which combined Greek naturalism with Indian spiritual themes, resulting in lifelike sculptures of the Buddha. Similarly, the Mughal era (1526–1857) brought Persian influences into Indian painting, architecture, and decorative arts, resulting in masterpieces like the Taj Mahal and the miniature paintings that blend Islamic aesthetics with indigenous themes.

Emphasis on Ornamentation

Ornamentation plays a central role in Indian art, whether in architecture, sculpture, painting, or textiles. Indian artists have an inherent love for detail, as seen in the intricate carvings of temples like the Khajuraho group of monuments or the Meenakshi Temple in Madurai. This penchant for embellishment extends to everyday objects, such as jewelry, textiles, and pottery, turning utilitarian items into works of art.

Humanism and Emotion

Indian art often portrays a deep sense of humanism and emotion, especially in depictions of divine and mythological figures. Unlike the static and idealized forms of some other classical traditions, Indian sculpture and painting frequently capture dynamic poses, nuanced expressions, and emotional depth. For example, the sculptures of Konark’s Sun Temple or the frescoes of Ajanta vividly depict human and divine forms in motion, telling stories with a profound emotional and spiritual resonance.

Music, Dance, and Literature

Indian art is deeply intertwined with other cultural expressions, such as music, dance, and literature. The performing arts, often depicted in sculpture and painting, have inspired and been inspired by visual art forms. Nataraja, the cosmic dance of Shiva, symbolizes the fusion of art forms and the rhythmic cycles of creation and destruction. Similarly, the Ragamala paintings visually represent musical modes (ragas), showcasing the interplay between auditory and visual aesthetics.

Focus on Materiality and Techniques

Indian artists have historically mastered a wide range of materials and techniques, including stone, metal, wood, terracotta, and textiles. The bronze sculptures of the Chola dynasty (9th–13th century CE) exemplify technical perfection, with finely detailed statues of Nataraja and other deities. The Ajanta frescoes demonstrate advanced knowledge of pigments, brushwork, and composition, revealing an exceptional understanding of artistic techniques.

The tradition of textile art in India, from the fine muslin of Bengal to the vibrant silk brocades of Banaras, showcases unparalleled craftsmanship. These textiles were highly sought after in global trade networks, underlining the significance of Indian art in the broader economic and cultural exchanges of the ancient and medieval worlds.

Patronage and Social Context

The role of patronage is crucial in understanding Indian art. Rulers, religious institutions, and wealthy merchants often sponsored monumental architectural projects, sculptures, and manuscripts. The Mauryan emperor Ashoka commissioned the iconic Ashokan pillars, inscribed with edicts promoting Buddhist principles, while the Mughal emperors supported the creation of grand structures like the Red Fort and Humayun’s Tomb.

Art also flourished in more modest settings, reflecting the lives and aspirations of ordinary people. Folk and tribal art traditions, such as Warli paintings from Maharashtra or the Gond art of central India, offer unique perspectives on the natural world, community life, and spirituality.

Philosophical Underpinnings

Indian art is deeply rooted in philosophical and metaphysical ideas, often reflecting concepts like dharma (righteousness), moksha (liberation), and the interconnectedness of life. The focus on symmetry, balance, and proportion in Indian temple architecture reflects a cosmic order, mirroring the principles of Vastu Shastra.

The works of thinkers like Ananda Coomaraswamy emphasize the unity of art and spirituality in Indian culture. Coomaraswamy argued that Indian art transcends the material world, serving as a bridge between the earthly and the divine.

Conclusion

The main features of Indian art—its spiritual depth, symbolic richness, diversity, adaptability, and technical mastery—reflect the cultural and historical complexity of the subcontinent. Rooted in ancient traditions yet continuously evolving, Indian art remains a testament to the enduring creativity and resilience of its people. Whether through the grandeur of temple architecture, the delicacy of miniature paintings, or the vibrant expressions of folk traditions, Indian art continues to inspire and captivate, offering insights into the timeless human quest for beauty, meaning, and transcendence.

Pre-historic paintings offer a captivating glimpse into the artistic expressions of our ancient ancestors, shedding light on the early human cultures that existed long before written history. These artworks, dating back tens of thousands of years, were typically created on cave walls, rock surfaces, and other natural canvases using rudimentary tools and pigments derived from local materials like minerals, charcoal, and plant extracts. The subject matter of prehistoric paintings often revolved around hunting scenes, animals, and stylized human figures. Some of the most renowned examples include the magnificent cave paintings found in locations like Lascaux in France and Altamira in Spain, which reveal a remarkable level of skill and creativity even with limited resources.

The significance of prehistoric paintings lies not only in their aesthetic appeal but also in their role as a form of communication and storytelling. These ancient artworks are thought to have served various purposes, from recording important events and rituals to expressing spiritual beliefs and ensuring the survival of knowledge across generations. They provide valuable insights into the daily life, beliefs, and artistic capabilities of early humans and have deepened our understanding of our cultural heritage. The preservation of prehistoric paintings offers a bridge to the past, enabling us to connect with our ancestors and appreciate the rich tapestry of human history that spans millennia.

The proliferation of artistic activities in Upper Paleolithic Times

- Prehistoric paintings have been found in many parts of the world, and by the Upper Paleolithic times, there was a proliferation of artistic activities.

- Around the world, the walls of many caves from this time are full of finely carved and painted pictures of animals that the cave-dwellers hunted.

- The subjects of their drawings were human figures, human activities, geometric designs, and symbols.

- In India, the earliest paintings have been reported from the Upper Palaeolithic times.

Significance of Prehistoric Paintings

These prehistoric paintings help us to understand early human beings, their lifestyle, their food habits, their daily activities, and, above all, they help us understand their mind and the way they thought.

Discovery of Prehistoric Rock Paintings in India

- The first discovery of rock paintings in India was made in 1867–68 by an archaeologist, Archibold Carlleyle, twelve years before the discovery of Altamira in Spain. Cockburn, Anderson, Mitra, and Ghosh were the early archaeologists who discovered a large number of sites in the Indian subcontinent.

- Remnants of rock paintings have been found on the walls of caves situated in several districts of Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, and Bihar. Some paintings have also been reported from the Kumaon hills in Uttarakhand.

Categories of Paintings

- The rock shelters on the banks of the River Suyal at Lakhudiyar, about twenty kilometers on the Almora– Barechina road, bear these prehistoric paintings. Lakhudiyar means one lakh caves.

- The paintings here can be divided into three categories: man, animal, and geometric patterns in white, black, and red ochre.

- Humans are represented in stick-like forms. A long-snouted animal, a fox, and a multiple-legged lizard are the main animal motifs. Wavy lines, rectangle-filled geometric designs, and groups of dots can also be seen here.

- One of the interesting scenes depicted here is of hand-linked dancing human figures. The granite rocks of Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh provided suitable canvases to the Neolithic man for his paintings. There are several such sites, but more famous among them are Kupgallu, Piklihal, and Tekkalkota.

Evolution of Prehistoric Paintings

Upper Paleolithic Period

- The paintings of the Upper Palaeolithic phase are linear representations, in green and dark red, of huge animal figures, such as bison, elephants, tigers, rhinos, and boars, besides stick-like human figures.

- Most paintings consist of geometrical patterns. The green paintings are of dancers and the red ones of hunters.

- The largest and most spectacular rock shelter is located in the Vindhya hills at Bhimbetka in Madhya Pradesh.

- The caves of Bhimbetka were discovered in 1957–58 by eminent archaeologist S. Wakankar.

- The themes of paintings found here range from mundane events of daily life in those times to sacred and royal images.

Mesolithic Period

- The largest prehistoric paintings discovered in India belong to this period. During this period, the themes multiply, but the paintings are smaller in size.

- Hunting scenes predominate. The hunters are shown wearing simple clothes and ornaments.

- In some paintings, men have been adorned with elaborate head-dresses, and sometimes painted with head masks.

- In the pre-historic paintings found in India, animals are depicted in their naturalistic style, while human beings are depicted stylistically.

- Prominent Mesolithic sites where these paintings are found include Langhnaj in Gujarat, Bhimbetka, and Adamagarh in Madhya Pradesh, and SanganaKallu in Karnataka.

Chalcolithic painting

- The paintings of the Chalcolithic period reveal the association, contact, and mutual exchange of requirements of the cave dwellers of this area with settled agricultural communities of the Malwa plains.

- Many times, Chalcolithic ceramics and rock paintings bear common motifs, such as cross-hatched squares, lattices, pottery, and metal tools.

- The primitive artists used many colors, including various shades of white, yellow, orange, red ochre, purple, brown, green, and black.

- Red was obtained from haematite (geru), green from a green variety of a stone called chalcedony, and white might have been made out of limestone. To make the paint, the rock or mineral was first ground into a powder, which was then mixed with water and a thick or sticky substance such as animal fat gum or resin from trees. Brushes were made of plant fiber.

- The colors have remained intact because of the chemical reaction of the oxide present on the surface of the rocks.

- The pre-historic paintings found in India are unique in their depiction of both men and animals engaged in the struggle for survival.

- The paintings of individual animals show the mastery of the skill of the primitive artist in drawing these forms.

- Both proportion and tonal effect have been realistically maintained in them.

- These paintings have survived for such a long period due to the natural conditions of the caves, such as a lack of light and moisture, and also because of the chemical reaction of the oxide present on the surface of the rocks.

- More animal figures than human figures are depicted in cave paintings probably because animals played a significant role in the lives of prehistoric humans.

- Animals were sources of food, clothing, and other essential resources.

- Therefore, prehistoric humans would have observed and studied the behavior of animals closely, leading to their depiction in cave paintings. Additionally, animals may have been seen as powerful and awe-inspiring, leading to their frequent depiction in cave paintings.

Indian art, spanning over millennia, is a profound and intricate reflection of the subcontinent’s history, culture, spirituality, and socio-political developments. The statement, “Indian art is religious in nature,” holds a significant degree of validity, as religion has indeed been a central theme in the evolution of Indian art. However, to reduce Indian art solely to its religious dimensions would be an oversimplification, as it also encompasses themes of nature, daily life, human emotions, royalty, and political power.

Indian Art and Its Religious Core

Indian art, from its earliest manifestations, has been deeply intertwined with religious and spiritual themes. The Indus Valley Civilization (circa 2500–1500 BCE) offers evidence of early religious symbolism, such as seals depicting the proto-Shiva figure (Pashupati), mother goddess figurines, and sacred animals. These artifacts highlight the civilizational tendency to intertwine artistic expression with beliefs in fertility, protection, and divine power.

With the rise of organized religions like Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism, the spiritual dimension of Indian art flourished. For instance, Buddhist art, seen in stupas like those at Sanchi and Bharhut, as well as the rock-cut caves of Ajanta and Ellora, reflects themes of the Buddha’s life, his teachings, and the concept of nirvana. Similarly, Hindu temple architecture, such as the grandiose temples of Khajuraho, Konark, and Brihadeeswarar, is a celebration of divine forms and cosmic order. These temples are richly adorned with sculptures of deities like Shiva, Vishnu, and Durga, showcasing mythological narratives and spiritual symbolism.

Religious art was not limited to sculpture and architecture; miniature paintings like the Mughal and Rajput schools also carried themes of divine love, as seen in depictions of Krishna and Radha in the Bhakti tradition. Jain manuscripts and Buddhist Thangkas, richly illustrated with meticulous detail, were visual aids for spiritual contemplation and storytelling.

Beyond the Religious Lens

While religion has been a dominant force, Indian art is not confined to it. Secular themes and humanistic expressions have equally thrived. The Indus Valley seals with geometric designs, dancing figures, and depictions of daily activities underscore a focus on life and creativity beyond ritualistic connotations.

The Gupta and Mauryan periods, often regarded as classical eras of Indian art, brought forth an aesthetic that combined religious ideals with worldly sophistication. The Ashokan pillars were inscribed with edicts that promoted ethical governance rather than explicit religious doctrines. Similarly, the Mughal era brought a shift towards more secular art forms, blending Persian and Indian styles. Miniature paintings during this period often portrayed courtly life, hunting scenes, and historical events.

Nature and aesthetic pleasure played a significant role, as seen in the Mughal gardens, the decorative motifs of floral and geometric designs in Mughal architecture, and the emphasis on beauty and sensuality in sculptures such as the apsaras in Khajuraho.

Salient Features of Indian Art

The salient features of Indian art, whether religious or secular, are as follows:

Diversity and Syncretism: Indian art is a melting pot of influences, from Persian and Greek to Central Asian and indigenous traditions. The Gandhara School of Art, for instance, blends Hellenistic and Indian elements in Buddhist iconography.

Symbolism and Allegory: Indian art often employs symbolism to communicate complex ideas. For example, the lotus is a recurring motif representing purity and spiritual awakening, while temple sculptures often depict cosmic functions through intricate carvings.

Unity in Diversity: Despite regional variations, Indian art maintains thematic and philosophical coherence, reflecting shared cultural and spiritual values.

Narrative Art: From the storytelling panels of Buddhist stupas to the epics painted in miniature forms, Indian art has a strong narrative tradition.

Integration of Functionality and Aesthetics: Indian art does not separate form from utility. Temples and palaces, while being functional, are also marvels of artistic and architectural innovation.

Human-Centric Approach: Even in religious contexts, Indian art often emphasizes human emotions and experiences. The serene smile of the Buddha or the dynamic forms of Shiva in Nataraja sculptures reflect universal human themes.

Conclusion

The statement that “Indian art is religious in nature” is both accurate and limited. While the religious ethos has undeniably shaped a significant portion of Indian artistic traditions, the canvas of Indian art is vast and multi-dimensional. It embodies not only spiritual aspirations but also the aesthetics of daily life, the grandeur of political power, and the beauty of nature. Indian art, thus, is not a monolithic entity but a vibrant tapestry of varied expressions. Understanding this diversity enriches our appreciation of the cultural and historical legacy of the Indian subcontinent, highlighting its unique ability to balance the sacred and the secular in a harmonious artistic synthesis.

The ancient art of India is a profound testament to the subcontinent’s rich history, spiritual ethos, and cultural diversity. It serves as a window into the values, beliefs, and societal structures of its time. Spanning several millennia, Indian art has evolved through various phases, encompassing a wide array of forms such as architecture, sculpture, painting, and crafts. Each phase bears the imprint of distinct cultural, political, and religious influences, reflecting the dynamism of Indian civilization.

Integration of Religion and Art

A defining feature of ancient Indian art is its profound religious orientation. Much of it was created as a medium for spiritual expression and to communicate divine concepts to the masses. The earliest examples can be traced back to the Indus Valley Civilization (circa 2500–1500 BCE), where seals and figurines hint at proto-religious themes. The dancing girl of Mohenjo-daro and the priest-king statue demonstrate a fusion of artistic skill with potential spiritual symbolism.

As organized religions like Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism emerged, their influence on art became pronounced. Buddhist stupas, such as those at Sanchi and Amaravati, were constructed as architectural representations of the cosmic order. The stupas’ intricate carvings depict the Buddha’s life, the Jataka tales, and symbols like the lotus and wheel, which convey profound philosophical meanings. Similarly, Hindu temples such as those at Khajuraho and Konark were adorned with sculptures representing deities, mythological narratives, and cosmic functions, often blending spiritual messages with aesthetic appeal.

However, ancient Indian art was not solely confined to religious themes. Secular art also thrived, capturing aspects of daily life, nature, and royal grandeur, albeit often with an undercurrent of spiritual philosophy.

Symbolism and Allegory

Symbolism is a hallmark of ancient Indian art, where physical forms often serve as metaphors for abstract ideas. The lotus symbolizes purity and spiritual enlightenment, while the chakra (wheel) represents the cycle of life and dharma. The Nataraja form of Shiva, depicting the cosmic dance of creation and destruction, encapsulates profound philosophical concepts through dynamic visual representation. The recurring use of animals like lions, elephants, and peacocks reflects their symbolic significance in both religious and royal contexts.

Narrative Tradition

Ancient Indian art is deeply narrative in nature, serving as a medium to tell stories and convey moral or spiritual lessons. The rock-cut caves of Ajanta are a striking example, with their frescoes illustrating episodes from the Buddha’s life and the Jataka tales. These narratives are rendered with meticulous detail and emotional depth, drawing the viewer into the story. Similarly, the sculptural panels of temples and stupas often depict mythological episodes, emphasizing moral and spiritual ideals.

Human-Centric and Emotional Expression

One of the remarkable aspects of ancient Indian art is its human-centric approach, which emphasizes human emotions, forms, and experiences, even in religious contexts. Sculptures like the serene Buddha statues of Sarnath and the dynamic apsaras (celestial dancers) of Khajuraho capture the full range of human expression. The art emphasizes physical grace and spiritual tranquility, often merging the two seamlessly. The emotional depth seen in figures—whether divine, royal, or common—is a testament to the sophisticated understanding of human psychology.

Integration of Nature

Nature plays a significant role in ancient Indian art, often depicted not just as a backdrop but as a living, integral part of the cosmos. Flora and fauna are common motifs, symbolizing fertility, abundance, and the interconnectedness of life. The Yaksha and Yakshi sculptures, representing nature spirits, embody this harmony with the natural world. Architectural elements, like temple gardens and water bodies, further reflect this integration.

Diversity in Styles and Techniques

The vast geographical expanse and cultural diversity of India are reflected in the varied styles and techniques of ancient art. For example, the Gandhara School of Art, influenced by Hellenistic and Persian traditions, is characterized by realistic depictions of the human form and intricate drapery in its Buddhist sculptures. In contrast, the Mathura School is more indigenous in style, marked by robust, sensuous figures and a focus on symbolic expression. The Dravidian and Nagara styles of temple architecture, each with its distinct characteristics, illustrate regional variations in design and construction.

Architectural Innovation

Ancient Indian architecture stands out for its innovation and grandeur. The rock-cut caves of Ajanta, Ellora, and Elephanta showcase incredible skill in carving intricate structures directly into cliffs. The stupas, chaityas (prayer halls), and viharas (monastic residences) of Buddhism were not only places of worship but also architectural marvels. Hindu temples, like the Brihadeeswarar Temple in Tamil Nadu, exhibit sophisticated engineering and design principles, from towering vimanas to intricately carved mandapas (pillared halls). The use of materials like sandstone, granite, and laterite highlights the technical mastery of ancient Indian craftsmen.

Aesthetic and Functional Unity

Ancient Indian art exhibits a seamless integration of aesthetics and functionality. Whether it was the planning of urban spaces in the Indus Valley Civilization, the construction of water reservoirs, or the design of temples, beauty and utility were intertwined. The sculptures and carvings on temples often served both decorative and educational purposes, conveying moral and spiritual lessons to devotees.

Legacy and Cultural Continuity

A salient feature of ancient Indian art is its enduring legacy. The artistic traditions established during ancient times continue to influence modern Indian art and culture. The continuity of motifs, styles, and techniques underscores the resilience and adaptability of Indian art. Festivals, rituals, and contemporary crafts often draw upon ancient artistic themes, keeping this rich heritage alive.

Conclusion

Ancient Indian art is a magnificent tapestry of religious devotion, cultural diversity, and human creativity. Its salient features—ranging from its spiritual depth and narrative richness to its aesthetic sophistication and symbolic complexity—underscore the ingenuity and philosophical depth of the civilizations that produced it. While deeply rooted in spirituality, ancient Indian art also reflects the humanistic and secular dimensions of life, embodying a holistic vision of existence. Its legacy continues to inspire and inform, reminding us of the enduring power of art as a medium of expression, communication, and transcendence.