Medieval & Modern – 2nd Year

Paper – II (B) (Short Notes)

History of Modern India (1858-1950)

Unit I

Government of India Act (1858) was passed on August 2,1858 which transferred the Company’s powers, territories and revenues to the British Crown. This act changed the designation of the “Governor General of India” to “Viceroy of India”. This significant Act was passed in the wake of the 1857 Revolt,It was sometimes referred to as the “Act for the Good Government of India.” It put a stop to Pitt’s India Act’s Dual Government Scheme.

Historical Background

- The 1858 mutiny was crushed, but it sent shockwaves across London. It sent a message that trading firms should not be permitted to remain as a political force.

- Since 1853, many English Traders and settlers had also developed a vested interest in India and their persistent complaint was the company had been neglecting their interests.

- According to British PM Palmerson, the utter irresponsibility and the cumbersome, Complex, irrational nature of the double government were primary defects in the Company’s rule.

- Parliament approved the Government of India Act on August 2, 1858, less than a month after the 1857 revolt, which led to power transfer.

- In India, the rule of the Company was superseded by the rule of the Crown, and the Secretary of State for India was to exercise the British Crown’s powers.

Key Provisions

- It abolished East India Company, India became a direct British Colony. Indian territories were to be governed in the name of the British queen.

- Abolished the dual government initiated by Pitt’s India Act of 1784.Court of Directors and the Board of Control were scrapped.

- The powers of the Court of Directors were shifted to and vested in the Secretary of State for India.(First Secretary of State for India: Lord Stanley)

- Secretary of State was to be assisted by a Council of 15 members .The council had only an advisory role. The Secretary of State for India was made chairman of the Council.

- Secretary of State would also act as a channel of communication between the British government and Indian Administration.

- Secretary of State would have complete authority and control over the Indian Administration. He was also vested with the power to send secret dispatches to India without consulting his council.

- British Parliament could question the Secretary of State in the Parliament regarding the state of affairs in India.

- The act put an end to the doctrine of lapse

- Governor General was given the title of Viceroy,who became a direct representative of Crown.( First Viceroy of India was Lord Canning )

- All power was vested in the hands of Viceroy.Viceroys were to be assisted by an Executive Council.

- Viceroy and the Governors of the various presidencies were appointed by the Crown.

- The act put an end to the doctrine of lapse. It was also decided that the remaining Indian Princes would have their independent status provided they accept British suzerainty.

- Pardon would be granted to all the Indians who participated in the mutiny except those who had killed British subjects.

- Provision for Indian Civil Services to administer the country,which would be controlled by Secretary of states.

Secretary Of State According To The Government Of India Act, 1858

- The Secretary of State was to be a British MP and a member of the Prime Minister’s cabinet.

- As a member of cabinet,was ultimately responsible to the British Parliament.

Defects

- It was dominated by absolute Imperial control with no representation for the people of India.

- The Secretary of State was the supreme authority and had a free hand in the administration of India and was responsible only to the British parliament.

Conclusion

Government of India Act, 1858 is also known as the act of good governance.But,it did not in any way alter the system of government in India. Most of the provisions were enacted to safeguard the jewel of British empire against any future threats or rebellions.

Indian Councils Act (1861) was passed by the British Parliament on August 1, 1861. It transformed the Executive Council to function as a cabinet run on the portfolio system. The involvement of Indians in the legislative process was the most notable feature of this Act. The Indian Councils Act of 1861 is an important landmark in the constitutional and political history of India.

Historical Background

- After the great revolt of 1857, the British Empire felt the urgent need of seeking the cooperation of its Indian subjects in the administration of India.

- In pursuit of this policy of association, three acts were enacted in 1861, 1892, and 1909.

Reasons for Enactment

- The Government of India Act of 1858 made important changes in the manner of governance from England, but it made no significant changes to the Indian government system.

- Following the 1857 Mutiny, there was a widespread belief in England that establishing a government in India without the participation of Indians in the administration would be extremely impossible.

- The 1833 Charter Act centralized the legislative process. It had only one representative in each of the four provinces, and it failed to pass legislation that was tailored to the needs of the people.

- The Governor General in Council was failing in his legislative duties and was unable to perform effectively due to lengthy procedures that caused delays in enactment.

Indian Councils Act of 1861 transformed the Executive Council to function as a cabinet run on the portfolio system. |

Provisions

- The trend of decentralisation was initiated by this act, which restored the legislative powers of the Bombay and Madras presidencies.

- Thus, the centralising trends that began with the Regulating Act of 1773 and culminated with the Charter Act of 1833 were reversed.

- This policy of legislative devolution resulted in the grant of almost complete internal autonomy to the provinces in 1937.

- By associating Indians with the law-making process, a new beginning was made for representative institutions.

- Providing for the provision of the Viceroy nominating some Indian members to his extended council.

- Subsequently, three Indians were included in this 1862 Legislative Council – the Raja of Benaras, the Maharaja of Patiala and Sir Dinkar Rao.

- Any bill relating to public revenue or debt, the military, religion, or foreign affairs could not be passed without the Governor-General’s approval.

- If necessary, the Viceroy had the authority to overrule the council.

- During emergencies, the Governor-General also had the authority to issue ordinances without the approval of the council.

- It provided for the establishment of the legislative councils for Bengal, North-Western Frontier Province and Punjab.

- It empowered the Viceroy to make rules and orders for a better and more convenient transaction of business in the council.

- It recognized the Portfolio System (introduced by Lord Canning in 1859) under which, a member of the Viceroy’s Council was made in-charge of one or more departments of the Government and was authorised to issue final orders on behalf of the Council on the matters of the concerned department.

- It also empowered Viceroy to issue ordinances, without the consent of the Legislative Council during an emergency. The ordinance will be valid for a period of 6 months.

Significance

- The Indian Councils Act of 1861 is a watershed moment in India’s constitutional and political history.

- For executive and legislative purposes, it changed the structure of the Governor General’s council.

- By involving Indians in the legislative process, a fresh beginning for representative institutions was established.

Defects

- The Legislative Council had a limited role. It was mainly advisory. No financial decisions were allowed.

- Although the Indians were elected, there were no official conditions for the inclusion of Indians in them.

- It allowed for the allocation of administrative positions by delegating legislative powers to the presidents of Bombay and Madras.

- The Governor-General had absolute power.

Conclusion

The Indian Councils Act 1861 is an important landmark in the constitutional and political history of India. It altered the composition of the Governor General’s Council for executive and legislative purposes. However, from India’s point of view, the act did little to improve the influence of Indians in the Legislative Council. The role of Council was limited to advice, and no financial discussion could take place.

Indian Councils Act of 1892 was passed with the objective of increasing the size of legislative councils in India thereby increasing the engagement of Indians with respect to the administration in British India. Following the foundation of the Indian National Congress, the Indian Councils Act of 1892 represents a significant milestone in India’s constitutional and political history.

Historical Background

- Following the Great Revolt of 1857, British realised that it needed to ensure the help of its Indian subjects in administering India.

- In addition, as nationalism grew in popularity, Indians became more cognizant of their rights.

- Following the founding of the Indian National Congress, the Indian Councils Act of 1892 represents a significant milestone in India’s constitutional and political history.

- After the Act of 1861, the growth of the Indian Constitution is essentially a story of political discontent and agitation interspersed with Council Reforms.

- The reforms that were reluctantly accepted were always found to be insufficient, resulting in dissatisfaction and a demand for more reforms.

- During the 1885-1889,as a result of the growing nationalism, the Indiana National Congress raised several demands through its sessions.

The following were the main demands:

- An ICS test was to be held simultaneously in England and India.

- Expansion of the Legislative Councils, including the adoption of the election-in-place-of-nomination basis.

- Opposition to Upper Burma’s annexation.

- Military spending should be reduced

- Ability to have previously forbidden financial chats.

Lord Dufferin, the Viceroy at the time, convened a commission to investigate the situation. On the other side, the Secretary of State opposed the idea of a direct election. However, he agreed to indirect electoral representation.

Objective

Increase in the size of various legislative councils in India thereby increasing the engagement of Indians with respect to the administration in British India.

Indian Councils Act of 1892 was passed with the objective of increasing the size of legislative councils in India. |

Key Provisions

- It raised the number of (non-official) members in the Central and Provincial Legislative Councils while keeping the official majority.

- Bombay – 8

- Madras – 20

- Bengal – 20

- North Western Province -15

- Oudh – 15

- Central Legislative Council minimum – 10, maximum 16

- The Act made it clear that the members appointed to the council were not there as representatives of any Indian body, but as nominees of the Governor-General.

- Members could now debate the budget without voting right. They were also barred from asking follow-up questions.

- The elected members were permitted to discuss official and internal matters.

- The Governor General in Council was given the authority to set rules for member nomination, subject to the approval of the Secretary of State for India.

- To elect members of the councils, an indirect election system was implemented.

- Members of provincial councils could be recommended by universities, district boards, municipalities, zamindars, and chambers of commerce.

- Provincial legislative councils were given more powers, including the ability to propose new laws or repeal old ones with the Governor General’s assent.

Significance

- It was the first step toward a representative system of government in contemporary India.

- The number of Indians increased, which was a good thing.

- Despite the fact that Indians did not have the power to veto the majority, their opinions were heard.

- The principle of election, which was accepted in 1892, allowed non-officials to have a free and open discussion on the government’s financial strategy. As a result, the administration had an opportunity to clear up misconceptions and respond to criticism.

- The statute gave members of the council the authority to issue interpellations on subjects of public concern.

Defects

- Despite being the first step toward a representative government in modern India, this act provided no benefits to the common man.

- This act created the stage for the development of numerous revolutionary forces in India because the British only made a minor concession.

- Many leaders, including Bal Gangadhar Tilak, faulted Congress’s moderate strategy of petitions and persuasions for the lack of significant progress and called for a more assertive policy against British rule.

Conclusion

The Indian Councils Act, 1892 is a significant milestone in India’s constitutional and political history. The act increased the size of various legislative councils in India thereby increasing the engagement of Indians with respect to the administration in British India. The Indian Councils Act, 1892 was the first step towards the representative government in modern India. The act created the stage for the development of revolutionary forces in India because the British only made a minor concession.

In 1880 A.D. election took place in England in which Liberal party came to power and its Leader Gladstone became the Prime Minister of England.

When Gladstone came to power, Viceroy Lord Lytton, resigned. Gladstone sent Lord Ripon as viceroy of India in 1880. Ripon was industrious, able with a deep moral earnestness.

He may be described as Gladstone’s agent in India. Ripon was liberal in his attitude and made some remarkable changes in the administrative system of India.

He granted various facilities to the Indians. P.E. Roberts writes about Lord Ripon, “He was a true liberal of Gladstonian Era with a strong belief in the virtues of peace, laissez faire, and self government.” Ripon was a true Democrat. He took some steps towards liberalizing the administration in India. His aim was to give popular and political education to the Indians. He formulated the local self government and laid the foundations of representative institutions in India.

Reforms

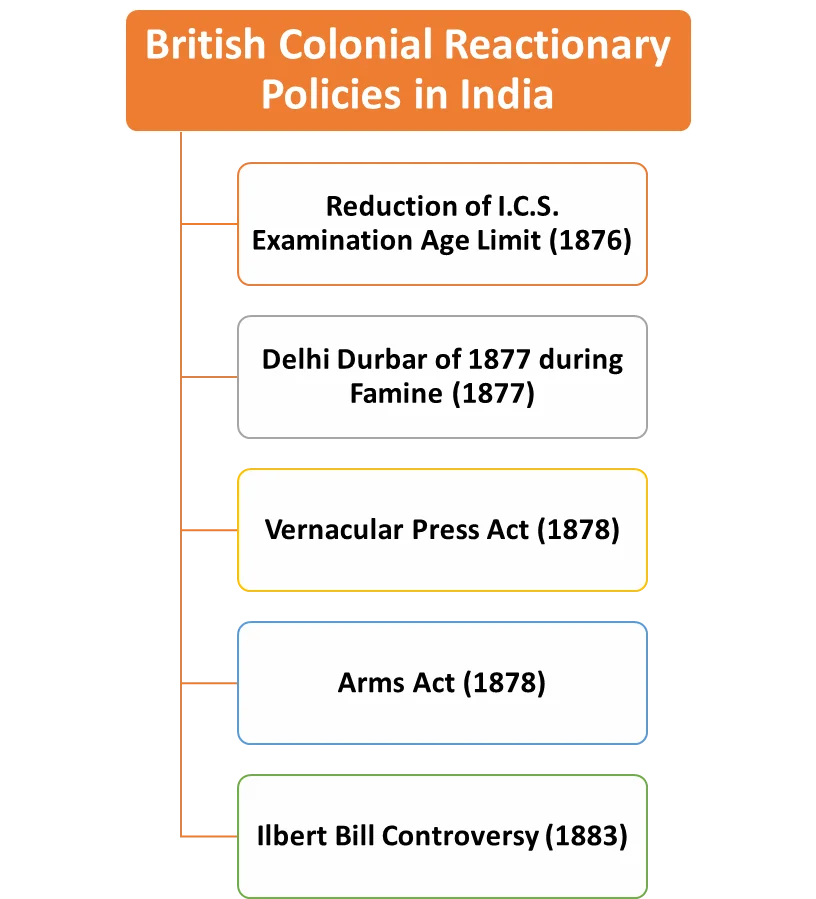

Repeal of Vernacular Press Act, 1882:

Lord Ripon repealed the Vernacular Press Act of 1878 passed by Lord Lytton by Act III of 1882 and thus news papers published in vernacular languages were allowed equal freedom with the rest of the Indian Press. This action of Ripon went a long way in conciliating public opinion.

The First Factory Act, 1881:

To improve the lot of the factory workers in towns, he passed the first Factory Act in 1881. The Act prohibited the employment of children under the age of seven, limited the number of working hours for children below the age of twelve and required that dangerous machinery should be fenced properly.

The Act also made provision for one hour rest during the working period and four days leave in a month for the workers. Inspectors were appointed to supervise the implementation of these measures. Thus for the first time he British Government tried to improve the working conditions of labourers in factories.

Economic Reforms: Financial Decentralization, 1882:

Lord Ripon like his predecesser, Lord Mayo was the follower of the policy of financial decentralization. Ripon divided the sources of revenue into three categories, Viz. Imperial, Provincial and Divided.

1. Imperial Heads:

Revenue from Customs, Posts and Telegraphs, Railways, Opium, Salt, Mint, Military Receipts, Land Revenue etc. were included in the imperial head. The Central Government was required to meet the expenses of central administration out of this revenue.

2. Provincial Heads:

Revenue from Jails, Medical slices, Printing, Roads, General Administration, etc. were included in the provincial heads. As the income from provincial heads was insufficient for provincial expenses, a part of Land revenue was assigned to the provinces.

3. Divided Heads:

The revenue from Excise, Stamps, Forests, Registration etc. was divided in equal proportion among the Central and Provincial Governments. The system of Divided Heads started by Ripon remained operative till it was modified by the Reforms of 1919.

Local Self Government

Lord Ripon is still remembered by the Indians for his attempts to establish local self government. Lord Ripon believed that the aim of Local Self Government was to train the Indians to manage their own affairs themselves.

Lord Ripon wrote, “What I want is a gradual training of the best, most intelligent and influential men in the community, to take an interest and active part in the management of their local affairs.” Ripon made it clear that he was advocating for the decentralization of administration not with a view of improving administration but as an instrument of political and popular education.

The idea of local self government was not a new one. Municipalities had already existed in big towns but the Government nominated the municipal commissioner. In rural areas there were committees to, manage local affairs such as sanitation, the repair and construction of roads, maintenance of ferries, education etc.

However the local committees were all under official control. Moreover the area served by their committees was too large. So that their members were not sufficiently acquitted with the needs of the people of different localities. Lord Ripon sought to remove these obstacles in the sphere of Local Self government by his resolution of 1882.

Accordingly, in rural areas District Boards and Local Boards known as “tahsil or “taluk boards were established. The members were to be elected by rent-payers rather than nominated by the Government. In towns the powers and responsibilities of the Municipalities were enlarged. The members were to be partly elected and partly nominated.

The chairman was to be a non-official member. The nominated members should not be more than one third of the total strength. The management of health, education, roads and communications were to remain under the control of the local boards. The local bodies were given certain financial powers but the Government retained the powers of inspection.

The local bodies were kept free from government control. But if the Boards were not discharging their duties properly, then the Government had the right to dissolve them. But usually, the government did not interfere in the affairs of the local bodies. The Local Self Government Acts were passed in different provinces during 1883-85. The work of lighting, cleaning of streets, sanitation, education, water supply, medical aid etc. was assigned to the local bodies of Madras, Punjab and Bengal.

Educational Reforms

Lord Ripon appointed an Education Commission in 1882 under the chairmanship of Sir William Hunter to review the progress of education in India, since Wood’s dispatch of 1854. The commission laid emphasis on the special responsibility of the state for the improvement and expansion of primary education.

It recommended that the management of elementary schools was to be entrusted to the newly established local and municipal boards under the supervision and control of the Government.

The Commission was satisfied with the system of Grants-in-aid, urged its extension for secondary and higher education and also recommended that the Government should withdraw as early as possible from the direct management of secondary schools. It also made suggestion for the improvement in commercial and vocational education. The commission also made suggestions for the spread of female education. Lord Ripon accepted most of the recommendations of the commission.

Other Reforms

During that time the recruitment to Indian Civil Service examination was held in England only and the age limit was 18. Ripon urged for the simultaneous examination both in India and in England He failed in his objective because he could not motivate the Government. However he succeeded in enhancing the age limit from 18 to 21.

The Ilbert Bill Controversy, 1883-84

Lord Ripon was a Liberal and he did not believe in castecism. So he sought to abolish “Judicial disqualifications based on race distinction.” According to the criminal procedure code of 1873 no magistrate or sessions judge except in presidency towns could try an European British subject unless he himself was of European birth.

Hence Lord Ripon sought the help of Sir C.P. Ilbert, the law member of the viceroy’s council to abolish the “judicial disqualification based on race distinction”. Sir Ilbert introduced a bill popularly known as the Ilbert Bill on 2nd February 1883 and through this bill the British European subjects were brought under the jurisdiction of Indian magistrates and judges.

But the bill was vehemently opposed by the European Community in India who formed a Defence Association to defence their special privileges. They passed resolutions urging the British Government to recall him before the expiration of the period of his office. After a prolonged tug of war Ripon bowed before the storm of agitation and modified the bill.

The amended bill provided that every European subject brought before a District Magistrate or Session Judge whether an Indian or European could claim to be tried by a Jury of twelve, at least seven of whom were to be Europeans or Americans. Though the Ilbert Bill controversy widened the racial feeling between the Indian and the Europeans yet it helped the Indians to learn the lesson that a powerful Government could be deviated from its purpose by organized agitation. It also intensified the feeling of unity among the Indian people.

Ripon resigned from his post in 1884 before the term of his viceroyalty was over. He was very popular with the Indians. According to Pandit Madan Mohan Malviya, “Ripon was the greatest and the most beloved Viceroy whom India has known.” Ripon is remembered according to Surendra Nath Banarjee for, “the Purity of his intentions, the loftiness of his ideas, righteousness of his policy and his hatred of Racial disqualifications.”

At the time of his departure for England the priests blessed him and offered him gifts. He was the only person who realized that the people of India should themselves make effort to attain freedom. Report’s doings in India marked the beginning of the political’ life in India. His departure was followed by the establishment of Indian National Congress in 1885.

Policy of Paramountcy means supremacy of British authority over Indian affairs.The policy emphasises Governor General’s right to intervene in the internal affairs of the Indian princely states, and to annex them if required. Lord Warren Hastings instituted the policy of Paramountcy who was Governor-General of India between 1813 to 1823.

The policy of Paramountcy: Concept

- A new policy of “paramountcy” was instituted under Lord Hastings (Governor-General from 1813 to 1823).

- The company maintained that because its power was preeminent or superior, it could annex or threaten to annex any Indian state.

- This was considered as the reference groundwork for other later British policies.

- The East India Company maintained that its powers were stronger than those of Indian states and that its powers were supreme or paramount, according to the Policy of Paramountcy.

- Because of Russian invasion fears, the British shifted control in the northwest during these decades.

- Between 1838 and 1842, the British fought a long war with Afghanistan, establishing an indirect company administration in the country.

- Sindh was conquered, Punjab was annexed after two prolonged wars in 1849 ruled by Maharaja Ranjit Singh.

British Paramountcy: Evolution

The evolution of British paramountcy occurred through various means such as the policy of ring-fencing, subordinate isolation, and subordinate union. The British developed the concept of paramountcy through a variety of tactics, including direct annexation via wars and a subsidiary alliance structure via treaties. Over the course of two centuries, the British aristocracy has gone through three distinct stages:

First Phase

- Between 1757 and 1813, the policy of ‘Ring Fence’ or non-interference was implemented.

- During this time, they did their best to stay within the confines of a ring-fence. In other words, they attempted to strengthen their position in a specific region by refraining from interfering in other people’s concerns.

- They pursued this policy mostly due to the facts on the ground. Despite being one of India’s most formidable forces at the time, the British were not yet powerful enough to take on all or even part of the Indian powers at the same time.

- During this initial phase, however, the English began to emerge as the dominant power in India.

Second Phase

- The policy of subordinate isolation was implemented during the second 45-year period (1813-1858).

- During this time, they ascended to the position of supreme power, claiming dominance over all native states. They did not, however, claim Princely India as part of their Indian dominion.

- Furthermore, as the need for British Imperialism grew, there was a steady move from subordinate collaboration to annexation policy during this time. The policy of subordinate cooperation gave way to the policy of annexation during this 21-year period (1834-58).

- This approach, initially announced by the Court of Directors in 1834 and again repeated by them in 1841, was followed by all Governor Generals from William Bentinck to Dalhousie.

- Despite the fact that there were multiple precedents prior to Dalhousie, he pursued annexation with vigour and zeal, even establishing ideas such as the doctrine of lapse and maxim of the benefit of the governed (Maladministration of government).

- He seized Punjab through war during his eight-year reign. He also conquered ten states, starting with Satara and ending with Nagpur, using the doctrine of lapse.

- He used the excuse of maladministration or misgovernance in the case of Awadh, which was the British’s last annexation in India.

Third Phase

- Following the insurrection of 1857, the British began the policy of sub-ordinate unity, which lasted until 1947.

- Following the 1857 insurrection, the British decided to abandon their annexation policy in favour of protecting the original states.

- During the revolt, the vast majority of native rulers remained loyal to the British and even assisted them in defeating the revolt.

- As a result of the revolt, the British learned an essential lesson: keeping the original state would be far more beneficial to them than annexing these states.

- The British will now justify their new approach by claiming that they now have an empire in India that includes not only British India but also princely India.

- As a result , annexing something that already belongs to them is pointless. The fact that there was no more useful land to be annexed in India was also a major factor in the refusal to add any more territory.

- The Queen’s proclamation of 1858 outlined this new policy of subordinate unity, which was fully adopted by the Government of India Act, 1858.

- The local rulers were now offered eternal life in writing in exchange for their loyalty and effectiveness. Due to the failure of naturally born male successors, 160 of the 562 native monarchs of the period were given special permission to go for adoption.

- Furthermore, the English showed their hesitation to conquer any native state in the notable examples of Baroda (1874) and Manipur (1881).

- However, they intervened in both situations to demonstrate that they would not tolerate either disloyalty or inefficiency.

The policy of Paramountcy: Resistance of States

- The minor state of Kitoor, which is now part of Karnataka, disputed this approach.

- Rani Channamma spearheaded the resistance movement against the British.

- Rani Channamma was apprehended in 1824 and died in 1829 while being imprisoned.

- Chennamma was born in Kakati, Karnataka’s Belagavi district.

- When she married Raja Mallasarja of the Desai family, she became the queen of Kitturu (now Karnataka). They had a son who died in 1824. She adopted another child, Shivalingappa, after her son died and proclaimed him heir to the crown. The British East India Company, however, refused to accept this because of the Doctrine of Lapse, an annexation doctrine created by the British East India Company.

- Rayanna, a poor chowkidar from Sangoli in Kitoor, led the resistance.

- In 1830, the British apprehended him and executed him.

- Rayanna, a poor chowkidar from Sangoli in Kitoor, led the resistance,in 1830, the British apprehended him and executed him.

Policy of paramountcy – British Expansion

Conclusion

The system of paramountcy was just a system of limited sovereignty on the surface. In reality, it was a means for the Imperial State to recruit a solid base of support. The Imperial State’s support removed the need for rulers to seek legitimacy through patronage or discussion with their people. The colonial state turned India’s populace into subjects rather than citizens, both directly and indirectly through the princes.

- The three Anglo-Afghan Wars (1839-1919) saw Great Britain, operating out of its base in India, wanting to control the neighboring Afghanistan to oppose Russian influence there. The first war was of great significance historically for Afghanistan and the British.

- The Anglo-Afghan wars were a direct result of the Great game between Great Britain and Russia which began in 1830.

- The British were concerned about Russian advances in Central Asia. England used Afghanistan as a buffer state to protect all approaches to British India from a Russian invasion.

- British concern about the Russian influence on Afghanistan led to the First Anglo-Afghan War (from 1838 to 1842) and the Second Anglo-Afghan War (from 1878 to 1880). The Third Anglo-Afghan War began in May 1919 and lasted for a month.

- Great Britain no longer had control of Afghanistan’s foreign affairs after an armistice was signed on August 8, 1919.

A brief history of Afghanistan

- Afghanistan was an important crossroads, dominated by other civilizations throughout its history.

- The Gandhara kingdom (1500-530 BCE) was centered around the Peshawar valley and Swat River valley, and westwards towards Kabul.

- By 522 BCE Darius, the Great extended the boundaries of the Persian Empire into most of the region that is now Afghanistan.

- By 330 BCE Alexander, the Great conquered Persia and Afghanistan. Seleucus, a Macedonian officer during Alexander’s campaign, declared himself ruler of his own Seleucid Empire, which also included present-day Afghanistan.

- The region became was attacked by the Mauryan empire during Chandragupta Maurya’s reign. Seleucus and Chandragupta signed a peace treaty thus stopping the Mauryans at the Hindukush.

- The Ghaznavid and Ghurid dynasties ruled the region from 997 to the Mongol invasions in 1221. Later Timur incorporated the areas into the Timurid empire with the city of Herat as the capital.

- Babur also used Kabul as military headquarters from 1504, from where he launched into the Indian subcontinent.

- After centuries of invasions the nation finally began to take shape during the 18th century under the leadership of Ahmad Shah Durrani.

- By 1736 Persian ruler Nader Shah gained control of most of the region that is present-day Afghanistan. He was assassinated in 1747.

- After his death, Ahmad Shah Durrani was chosen to be the ruler of Afghanistan. Durrani extended Afghanistan’s borders into India during the 1760s.

First Anglo-Afghan War (1838-43)

- The British and Russian empires competed diplomatically for areas of influence in South Asia throughout the 19th century.

- The Afghans were in constant conflict with the Sikh kingdom which had conquered Peshawar. The unstable condition in the Afghan and Sindh regions along with the increasing power of the Sikh kingdom made the British fear attacks from the northwest frontier.

- Meanwhile, Dost Muhammad, the amir of Durrani empire was in talks with Russians to contain the Sikhs.

- The British East India Company sent envoys to Kabul for an alliance against Russia. Kabul demanded the restoration of Peshawar captured by the Sikh kingdom. The British were unsure of their power to deal with the Sikhs and hence refused Kabul’s demand.

- 1838: Great Britain, concerned about growing Persian and Russian influences, invaded Afghanistan. The invasion was ordered by Lord Auckland who was governor general at that time. He was in support of restoring the exiled Afghan ruler Shah Shoja to the throne of Kabul.

- 1839: The British in a surprise attack captured the fortress of Ghazni. The British effortlessly marched into Kabul and restored Shah Shoja to the throne of Kabul.

- The Afghans could not tolerate a foreign occupation or a king imposed on them by a foreign power, hence uprisings broke out.

- After fleeing to Balkh and then Bukhara, where he was captured, Dost Mohammad managed to escape from jail and returned to Afghanistan to join his partisans in fighting the British.

- 1840: Dost Muhammad had the upper hand in a fight at Parwan in 1840, but the next day he submitted to the British in Kabul. He and the majority of his family were sent back to India.

- 1842: The uprisings continued and the British found to hard to contain the Afghans, hence they decided to retreat. The whole English camp marched out of Kabul but was swarmed by bands of Afghans, and the retreat ended in a bloodbath. Shoja was also killed in Kabul as he was unpopular among the Afghans.

- 1843: The new governor-general of India, Lord Ellenborough, decided on the evacuation of Afghanistan, and in 1843 Dost Moḥammad returned to Kabul and was restored to the throne.

- The British were earlier aiming to attack Punjab as well but were countered by Maharaja Ranjit Singh. But his death in 1839 caused the Sikh kingdom to fall apart. Thus, the end of the First Anglo-Afghan war gave way to a series of Anglo-Sikh wars (1845-49).

- 1855: A treaty of friendship (Treaty of Peshawar) was signed between British India and Dost Mohammed of Kabul. The treaty was a ‘policy of non-interference’.

- Dost Mohammed stayed loyal to the treaty and refused to help the rebels during the ‘Revolt of 1857’.

- 1856: After the Crimean War, Russia turned its attention towards Central Asia yet again.

- After 1864, the British started strengthening Afghanistan as a powerful buffer state. They helped the Amir of Kabul is disciplining the internal rivals. The non-interference and occasional help stopped Afghanistan from aligning with Russia.

- This policy of the British in Afghanistan is called the “policy of masterly inactivity”.

Second Anglo-Afghan War (1878-80)

- The policy of non-interference did not last long. The 1870s saw a resurgence of imperialism and the Anglo-Russian rivalry intensified. Their commercial and financial interest in Central Asia clashed openly in the Balkans and West Asia.

- Lord Lytton was named governor-general of India by British Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli in 1875. Lytton was given orders to either combat the rising Russian influence in Afghanistan at the time of his appointment or use force to establish a secure border.

- Sometime after Lytton’s arrival in India, he informed Sher Ali Khan, Dost Mohammad’s third son and the heir apparent that he was dispatching a “mission” to Kabul. Lytton’s request to enter Afghanistan was denied by the emir.

- Lytton did not begin attacking the kingdom until 1878, when Afghan forces turned back Lytton’s envoy, Sir Neville Chamberlain, at the frontier while General Stolyetov of Russia was allowed entry into Kabul.

- 1878: The British attacked Afghanistan. Sher Ali fled his capital and country and died in exile early in 1879. The British occupied Kabul.

- Sher Ali’s son, Yakub Khan signed the ‘Treaty of Gandamak’ for peace in 1879 and he was recognized as the amir.

- He subsequently agreed to receive a permanent British embassy in Kabul.

- In addition, he agreed to conduct his foreign relations with other states in accordance with the advice of the British government.

- 1879: The Afghan rebels rose against foreign interference and the British envoy, Sir Louis Cavagnari, and his escort were murdered in Kabul.

- British again occupied Kabul in retaliation while Yakub Khan abdicated the throne.

- 1880: Lord Ripon replaces Lytton as the governor-general and went back to the policy of non-interference.

- Meanwhile, Abdur Rahman, nephew of Sher Ali and cousin of Yakub Khan was recognized as the new Amir. He agreed to maintain relations only with the British and no other foreign powers.

- British got full control of Afghanistan’s foreign affairs and the Amir became a dependent ruler.

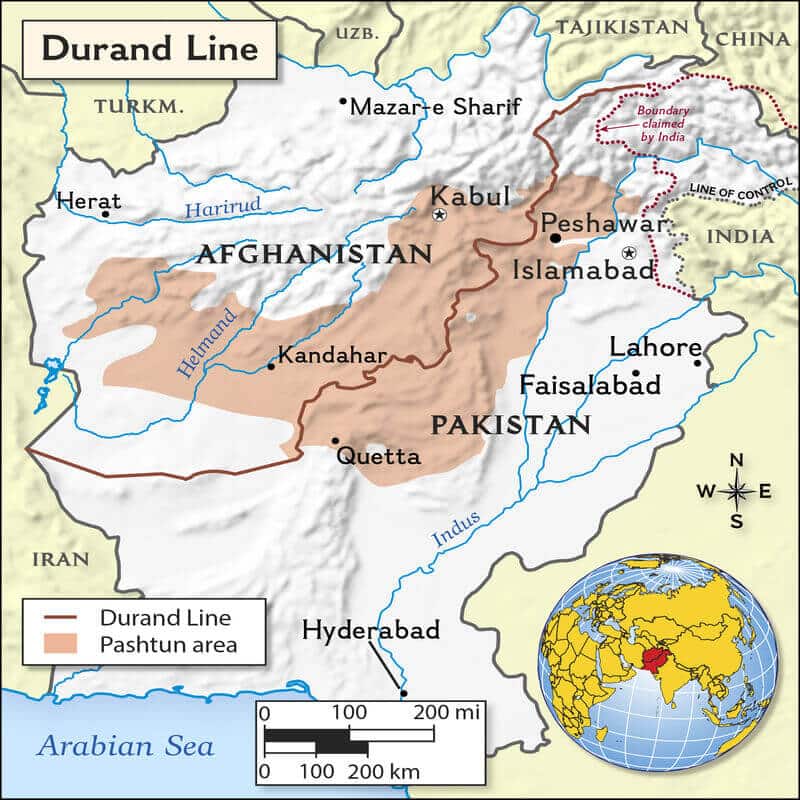

- 1893: The Durand line was drawn as the boundaries of modern Afghanistan by the British and the Russians. The line is named after the British civil servant Sir Henry Mortimer Durand who marked the line.

- Durand Line cut through Pashtun villages and has been the cause of continuing conflict between Afghanistan and Pakistan.

Battle of Saragarhi (1897)

The Battle of Saragarhi was fought on 12 September 1897, in the then North-West Frontier Province of British India, (now in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan).

- The conflict was concentrated on the Saragarhi garrison which was a communication post between Fort Lockhart and Fort Gulistan.

- The post was defended by 21 Sikh soldiers of the 36th Sikhs regiment of the British Indian Army against soldiers of Pashtun, and Orakzai tribes, more than 8 to 10 thousand in numbers.

The Battle of Saragarhi is considered one of the finest last stands in the military history of the world.

Third Anglo-Afghan War (1919)

- The outbreak of World War I (1914-18) and the Russian Revolution (1917) gave rise to strong anti-British sentiments and support for Ottoman turkey in most Islamic regions including Afghanistan.

- The removal of Russian influence and anti-British sentiments made the new ruler of Afghanistan Amanullah Khan declared total independence from Britain.

- This declaration launched the inconclusive Third Anglo-Afghan War in May 1919.

- Fighting was confined to a series of skirmishes between an ineffective Afghan army and a British Indian army exhausted from the heavy demands of World War I.

- A peace treaty, ‘The Treaty of Rawalpindi’ was signed in recognition of the independence of Afghanistan.

- British saw a strategic victory as the Durand line was reaffirmed as border between Afghanistan and British Raj.

- Afghanistan saw a diplomatic victory with full independence and sovereignty in foreign affairs.

- The final amended treaty was signed in 1921 before which the Afghans concluded a treaty of friendship with the new Bolshevik regime in the Soviet Union.

- Afghanistan thereby became one of the first states to recognize the Soviet government, and a “special relationship” evolved between the two governments that lasted until December 1979, when the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan during the Afghan War.

Impact of Anglo-Afghan Wars

- The Anglo-Afghan wars resulted in a botched boundary between Afghanistan and present-day Pakistan which is causing major trouble in the region even today.

- In Afghanistan, to this very day, no foreigners are viewed with as much suspicion as the British, but the shadows of the wars still remain.

The relationship between Burma (now Myanmar) and British India in the 19th century is a compelling narrative of conflict, diplomacy, and colonial ambition. This relationship evolved from cautious trade interactions into open hostility, culminating in Burma’s annexation by the British Empire in 1886. The annexation marked the end of Burma’s sovereignty under the Konbaung Dynasty and its incorporation into British India, reshaping its political, social, and economic landscape.

Early Interactions and Escalating Tensions

The initial encounters between the British and Burma were driven by mutual commercial interests. British merchants and the East India Company sought to expand their influence in Asia, identifying Burma as a land rich in natural resources, including teak, rubies, and fertile agricultural land. Burma’s strategic position, flanked by India and China, made it an attractive territory for British interests. Meanwhile, the Burmese Konbaung kings were engaged in their own imperial pursuits, seeking to consolidate power by expanding into Assam, Manipur, and Arakan, regions that brought them into direct conflict with British India.

The first major strain in relations emerged during the late 18th and early 19th centuries, as the Burmese monarchy’s territorial ambitions alarmed the British. Burma’s expansion into territories that bordered Bengal, combined with its increasing support for insurgencies in northeastern India, provoked British suspicion and hostility. By the 1820s, these tensions escalated into the First Anglo-Burmese War, marking the beginning of a series of conflicts that would determine Burma’s fate.

The First Anglo-Burmese War and Its Consequences

The First Anglo-Burmese War (1824–1826) was a direct result of the clash between Burma’s imperial ambitions and Britain’s need to secure its Indian frontiers. The war, the longest and most expensive conflict fought by the East India Company, was a defining moment in the relationship between the two powers. It was triggered by Burmese incursions into British-controlled Assam and Manipur, as well as disputes over territorial boundaries. The British, perceiving these actions as a threat to their security and trade, launched a military campaign against Burma.

The war was characterized by fierce battles, logistical challenges, and heavy casualties on both sides. The British, however, gained the upper hand due to their superior naval power and ability to control key waterways. By 1826, the British forced the Burmese to sue for peace, leading to the signing of the Treaty of Yandabo. This treaty marked a significant turning point, as Burma ceded the provinces of Arakan and Tenasserim, paid a hefty indemnity, and agreed to allow British diplomatic representation in Ava, the Burmese capital. Though the treaty ended the war, it planted seeds of resentment in Burma, as the loss of territory and national pride deeply affected the Konbaung rulers.

Renewed Conflict: The Second Anglo-Burmese War

The uneasy peace established by the Treaty of Yandabo did not last long. By the mid-19th century, tensions resurfaced, driven by disputes over trade and diplomatic protocols. The British were keen to expand their influence in Lower Burma, particularly in Rangoon, an emerging commercial hub. The Second Anglo-Burmese War (1852–1853) was precipitated by a trade dispute in Rangoon, where British merchants complained of harassment and extortion by Burmese officials. When the Burmese monarchy refused to address these grievances to Britain’s satisfaction, the British launched another military campaign.

Unlike the first war, the Second Anglo-Burmese War was swift and decisive. British forces quickly captured Rangoon and advanced into Pegu, effectively taking control of Lower Burma. The war ended without a formal treaty, but the British unilaterally annexed Lower Burma, incorporating it into British India. This annexation was significant, as it provided the British with control over Burma’s rice-exporting regions and deepened their economic stake in the country. For the Burmese monarchy, the loss of Lower Burma was a devastating blow, further weakening the Konbaung Dynasty and setting the stage for future conflict.

The Third Anglo-Burmese War and the Fall of the Konbaung Dynasty

By the late 19th century, Burma’s weakened monarchy faced mounting internal challenges and external pressures. The reign of King Thibaw Min, the last monarch of the Konbaung Dynasty, was marked by mismanagement and corruption, as well as an increasingly hostile relationship with the British. Thibaw’s attempts to forge alliances with France, a rising colonial power in Southeast Asia, alarmed the British, who viewed French influence in Burma as a direct threat to their interests.

The Third Anglo-Burmese War (1885) was the culmination of these tensions. The British, citing Thibaw’s monopolization of the teak and timber trade and alleged mistreatment of British merchants, launched a military campaign to overthrow the Burmese monarchy. The war was remarkably short, as British forces quickly advanced up the Irrawaddy River, capturing Mandalay, the royal capital, in November 1885. King Thibaw was captured and exiled to India, and the British declared Burma annexed.

The formal annexation of Burma occurred in January 1886, when Upper Burma was incorporated into the British Empire. With this act, Burma ceased to exist as an independent kingdom, becoming a province of British India. The annexation marked the end of centuries of Burmese sovereignty and the start of nearly six decades of colonial rule.

The Impact of British Annexation

The annexation of Burma had far-reaching consequences for its political, economic, and social structures. Politically, the abolition of the monarchy and traditional administrative systems disrupted Burmese governance. The British introduced a centralized colonial administration based on the Indian model, with British officials overseeing governance and the Indian Penal Code replacing Burmese legal traditions. This imposition of foreign systems alienated many Burmese, particularly the traditional elite.

Economically, the British focused on exploiting Burma’s natural resources for export. The rice industry became the cornerstone of Burma’s colonial economy, with vast tracts of agricultural land converted to rice cultivation. However, much of this land was controlled by Indian immigrants or British firms, marginalizing Burmese farmers. The export-driven economy enriched the British Empire but did little to improve the lives of ordinary Burmese, many of whom faced dispossession and poverty.

Culturally and socially, the annexation undermined Burma’s traditional institutions. The monarchy, which had been a unifying symbol of Burmese identity, was abolished, and the Buddhist clergy (Sangha) was increasingly marginalized under British rule. The British also encouraged Christian missionary activity, particularly among ethnic minorities such as the Karen and Chin, further fracturing Burmese society.

Resistance to British rule was widespread, with many Burmese taking up arms in guerrilla warfare. These resistance movements, though ultimately suppressed, reflected the deep dissatisfaction with colonial rule and the longing for independence. The seeds of Burma’s nationalist movement, which would gain momentum in the 20th century, were sown during this period.

Conclusion

The annexation of Burma in 1886 was the culmination of decades of conflict and colonial ambition. The British, driven by strategic and economic interests, systematically dismantled Burma’s sovereignty through a series of wars and treaties. While the annexation brought Burma into the global economy and introduced modern infrastructure, it also disrupted traditional society, eroded national identity, and created lasting grievances. The legacy of British rule in Burma is a complex one, marked by both development and destruction. The events of 1886 remain a pivotal chapter in Burma’s history, shaping its path toward independence and its struggles with identity and governance in the modern era.

Relations with Bhutan

- At the beginning of the Company’s rule, the relationship between India and Bhutan was hostile. There were frequent attacks by the Bhutanese in the Duars plains of British territory.

- Warren Hastings signed an Anglo-Bhutanese Treaty on April 25, 1774, to end the hostilities and establish friendly relations with Bhutan. This treaty permitted EIC to trade with Tibet through Bhutan’s territory.

- The Treaty of Yandabo (1826) handed over Assam to the British, bringing them into close contact with Bhutan.

- The Bhutanese took advantage of political instability in Northeast India after the Anglo-Burmese War (1824-26). They committed various acts of aggression, leading to encroachments and adding to their possessions of the Dooars. This led to an estranged relationship between the British India and Bhutan.

- The intermittent raids by the Bhutiyas on the Bengal side of the border further strained relations between India and Bhutan.

The EIC’s engagement with Bhutan started in 1772 after the Bhutanese invaded Cooch Behar (a city in West Bengal), which was a dependency of the EIC.

Duar War and Treaty of Sinchula (Ten Article Treaty of Rawa Pani) (1865)

- In 1863, a brief war broke out between the British and Bhutan. In 1864, the British launched the Duar War. Bhutan was defeated, and peace was concluded by the Treaty of Sinchula, signed in 1865, by which:

- Bhutan ceded all the Bengal and Assam Duars

- The British agreed to pay Bhutan an annual payment of Rs.50,000.

The relations of the Bhutan with Great Britain started growing to the extent that the Bhutanese king accompanied Col. Younghusband to visit Lhasa (Tibet) to sign a convention in 1904 through which Tibet agreed to end its special ties with Bhutan in favour of the Britishers.

Treaty of Punakha (Treaty of Friendship) (1910)

- A fresh treaty, the Treaty of Punakha, was concluded in 1910, by which:

- Bhutan surrendered her foreign relations to British India and accepted the latter as arbiter in her disputes with Cooch Behar and Sikkim.

- Britain increased the annual subsidy to Bhutan to Rs.100,000 and assured that they would not interfere in Bhutan’s internal affairs.

- After India’s independence, a new treaty was signed in 1949, and the government of India further increased the allotted payment to Bhutan to Rs 500,000 a year.

Relations with Sikkim

- By the end of the 18th century, the Gorkhas took control of Sikkim. However, after the Anglo-Nepal War (1814-16), the British restored Sikkim’s independence.

- The Treaty of Sugauli (1816) (between the British and Nepal): The British annexed the territories of the Sikkim captured by Nepal.

- The Treaty of Titalia (1817) (between the British and Sikkim): The British restored the territory of Sikkim to the Kingdom of Sikkim, ruled by Chogyal monarchs.

- The Treaty of Titalia was signed between the Chogyal (monarch) of the Kingdom of Sikkim and the British EIC.

- It returned Sikkimese land annexed by the Nepalese over the centuries and guaranteed the security of Sikkim by the British.

- The British had their vested interests in befriending Sikkim, including:

- To open a direct trade route through Sikkim to Tibet as an alternative to the route through Nepal.

- To counter increasing Russian intrusion into Tibet.

- The Anglo-Sikkimese ties began to deteriorate in 1835 when Sikkim had to give Darjeeling to the

British in return for an annual subsidy of Rs.3000. - Relations between Sikkim and the British soured further in 1849 when a minor quarrel led Dalhousie to send troops into Sikkim. This resulted in the British annexation of Darjeeling and a major portion of the Sikkimese Morang (terai) territory. Another clash occurred in 1860.

- In 1861, the Treaty of Tumlong reduced Sikkim to the status of a virtual protectorate.

- 1886, fresh trouble arose when the Tibetans tried to bring Sikkim under their control. The Government of India carried out military operations against the Tibetans in Sikkim in 1888. The final settlement came in 1890 with the signing of an Anglo-Chinese agreement.

Anglo-Chinese Agreement or Convention of Calcutta (1890)

- Anglo-Chinese Agreement was a treaty between Britain and China relating to Tibet and the Kingdom of Sikkim. The Viceroy of India, Lord Lansdowne, and the Chinese Amban in Tibet, Sheng Tai, signed the treaty on 17 March 1890 in Calcutta, India.

- The treaty recognised that Sikkim was a British protectorate over whose internal administration and foreign relations the Government of India had the right to exorcise exclusive control. It also demarcated the Sikkim–Tibet border.

- British protected states represented a more loose form of British suzerainty, where the local rulers retained control over the states’ internal affairs, and the British exercised control over defence and foreign affairs.

- China is said to have negotiated the treaty without consulting Tibet, and the Tibetans refused to recognise it.

Sikkim’s merger

- In 1950, Sikkim became a protectorate of India through a treaty signed between the then-Sikkim monarch, Tashi Namgyal, and the Indian government. This meant that while Sikkim was not part of India, it was also not a fully sovereign country.

- The Indian government managed Sikkim’s defence and foreign relations, while the Chogyal, as the monarchy, controlled the internal administration.

- From the 1950s to the 1970s, the discontent against the monarchy in Sikkim grew because of growing inequality and feudal control.

- Thousands of protesters surrounded the royal palace during the 1973 anti-monarchy protests. Finally, in the same year, a tripartite agreement was signed between the Chogyal, the Indian government, and three major political parties to introduce major political reforms.

- In 1974, elections were held, and the Sikkim State Congress, which advocated greater integration with India, won.

- The assembly first sought the status of ‘associate state’ and then, in April 1975, passed a resolution asking for full integration with India. This was followed by a referendum that put a stamp of popular approval on the assembly’s request.

- The Indian Parliament immediately accepted this request, and Sikkim became the 22nd State of the Indian Union in 1975.

Relations with Tibet

Nominal Suzerainty of the Chinese Empire

- Tibet is located to the north of India and is separated from India by the Himalayan mountain range.

- Tibet was ruled by a Buddhist religious aristocracy (the lamas). The chief political authority was exercised by the Dalai Lama, who claimed to be the living incarnation of the power of the Buddha.

- The lamas wanted to isolate Tibet from the rest of the world. They acknowledged the nominal suzerainty of the Chinese Empire to repel foreign threats.

- With no threat from Tibet and China being militarily weak, the British interest in Tibet was purely commercial in the beginning.

- Warren Hastings showed keen commercial interest in the region and sent two missions, one in 1774 and another in 1783. However, the isolationist and suspicious Dalai Lama (the ruler) declined the offer to establish trade relations with the British EIC.

British interest in Tibet

- Both Britain and Russia were keen to promote relations with Tibet. British policy towards Tibet was governed by economic and political considerations.

- Economically, the British wanted to develop the Indo-Tibetan trade and exploit its rich mineral resources.

- Politically, they wanted to safeguard the northern frontier of India.

- However, until the end of the 19th century, the Tibetan authorities blocked all British efforts to penetrate it.

- At the beginning of the 20th century, Russian influence in Tibet increased. The British government perceived this as threatening India’s security from the northern side.

- Under Lord Curzon, the British government decided to take immediate action to counter Russian moves and bring Tibet under its system of protected border states.

- According to some historians, the Russian danger was not real and was merely used as an excuse by Curzon to intervene in Tibet.

Expedition to Lhasa

- In March 1904, Curzon sent a military expedition to Lhasa, the Capital of Tibet, under Francis Young-husbdnd. Younghusbdnd started his march into Tibet through Sikkim. During this expedition, 700 Tibetans were killed.

- Younghusbdnd reached Lhasa in August 1904, and after prolonged negotiations, a Treaty of Lhasa was signed, by which:

- Tibet was reduced to the status of a protectorate of the British.

- Tibet was to pay Rs. 25 lakhs as indemnity

- The Chumbi Valley was to be occupied by the British for three years.

- A British trade mission was to be stationed at Gyantse (a town in Tibet).

- The British agreed not to interfere in Tibet’s internal affairs. On their part, the Tibetans agreed not to admit the representatives of any foreign power into Tibet.

- The British accomplished little during the Tibetan expedition. Although it led to Russia’s withdrawal from Tibet, it confirmed China’s suzerainty in 1906.

Anglo-Chinese Convention (1906)

- Anglo-Chinese Convention was a treaty signed between the Qing Dynasty of China and the British Empire in 1906.

- This treaty, which was signed in the absence of Tibet, reaffirmed the Chinese suzerainty over Tibet. By the terms of the treaty:

- The British agreed not to annex or interfere in Tibet in return for indemnity from the Chinese

government. - China agreed not to permit any other foreign state to interfere with Tibet’s territory or internal administration.

- The British agreed not to annex or interfere in Tibet in return for indemnity from the Chinese

Shimla Conference 1913

- After the Chinese Revolution of 1911, the. Dalai Lama announced his independence.

- Instead of recognising Tibet as an independent state, the British invited representatives of China and Tibet to a tripartite conference in Shimla in May 1913. At the conference:

- The Tibetans sought to acknowledge their independence, repudiate the Anglo-Chinese Convention of 1906, and the revision of the trade regulations.

- The Chinese Government wanted that their sovereignty over Tibet should be recognised and their right to control foreign and military affairs of the country should be accepted.

- The British were more interested in the Indo-Tibetan border than Tibet’s internal problems.

- On 27 April 1914, two agreements were concluded.

- Tibet was divided into two zones, ‘Outer Tibet’ and ‘Inner Tibet’. Chinese suzerainty over the whole of Tibet was recognised.

- Outer Tibet would remain in the hands of the Tibetan Government at Lhasa under Chinese suzerainty, but China would not interfere in its administration.

- Inner Tibet would be under the jurisdiction of the Chinese government.

- It was decided to draw a boundary between Tibet and British India (McMahon line).

- Tibet was divided into two zones, ‘Outer Tibet’ and ‘Inner Tibet’. Chinese suzerainty over the whole of Tibet was recognised.

- However, China refused to ratify the conference’s agreement (including the demarcated border) and did not accept Tibet as an independent nation.

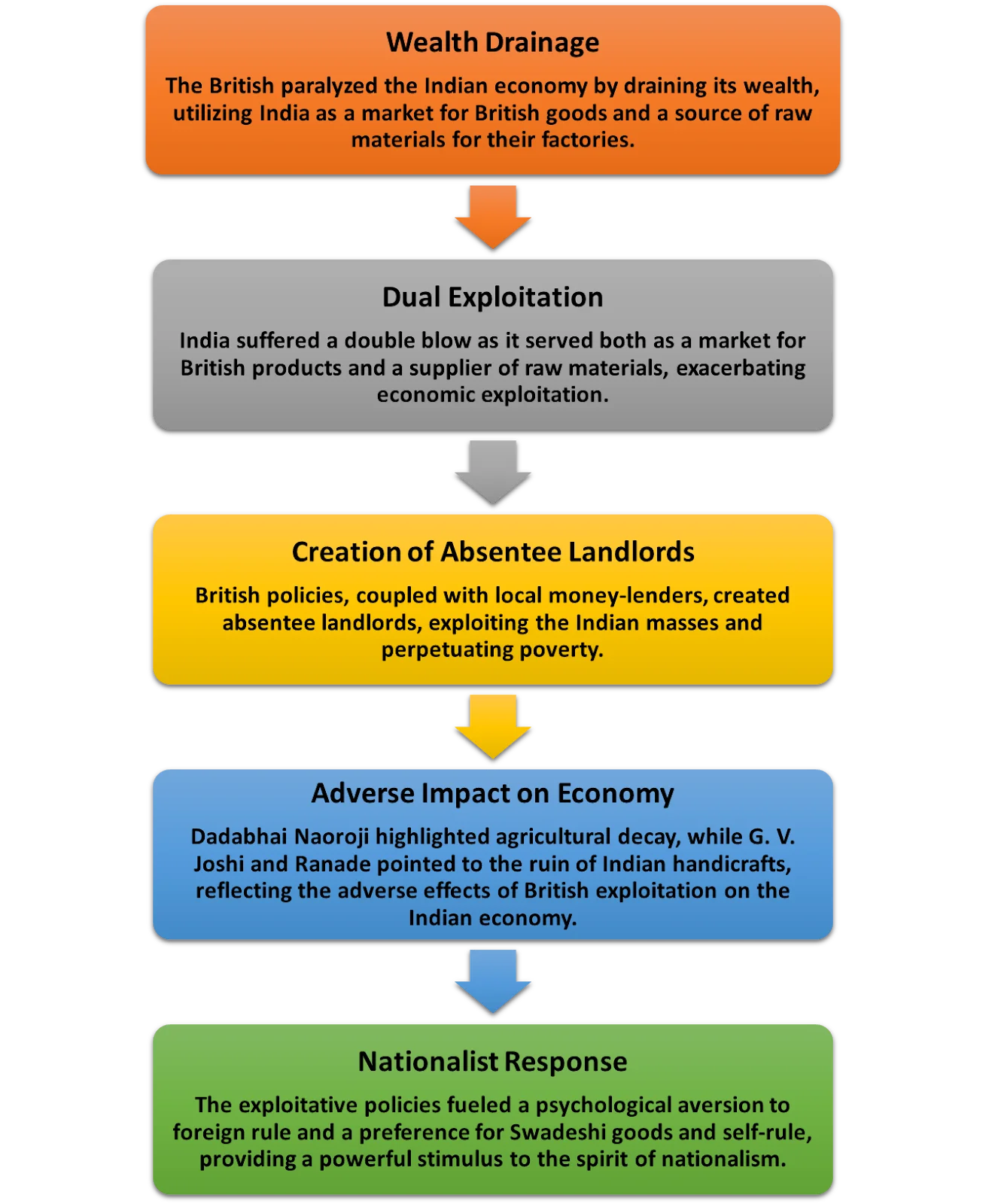

The 19th century in India was a period of profound socio-economic and political changes under British colonial rule. Among these transformations was the emergence of the middle class and a new elite class, groups that played a pivotal role in the intellectual, political, and cultural developments of the period. These groups were distinct from the traditional aristocracy and peasantry, representing a new socio-economic force shaped by colonial policies, education, and economic changes. Their attitudes toward social reform evolved significantly over the decades, particularly after 1870, as they navigated the challenges of modernity and tradition.

Factors Responsible for the Rise of the Middle and New Elite Class

1. British Educational Policies:

The cornerstone of the middle class’s emergence was the introduction of Western education. Starting with the Charter Act of 1813, British policies aimed to produce a class of Indians proficient in English to serve as intermediaries in administration and commerce. Lord Macaulay’s Minute on Education (1835) emphasized English as the medium of instruction, creating a generation of Indians well-versed in Western thought, science, and philosophy. Institutions like Hindu College (1817) in Calcutta and the universities of Calcutta, Bombay, and Madras (1857) produced a Western-educated intelligentsia that formed the nucleus of the new middle class.

2. Expansion of Administrative and Professional Opportunities:

The British administrative framework expanded significantly in the 19th century, creating new job opportunities. Indians were recruited into subordinate positions in the Indian Civil Service, legal professions, railways, postal services, and education. This professional class, though subordinate to Europeans, gained social prestige and financial security, becoming the backbone of the new elite.

3. Growth of Urban Centers:

Urbanization played a crucial role in the emergence of the middle class. Cities like Calcutta, Bombay, Madras, and Lahore became administrative, industrial, and cultural hubs under colonial rule. These cities provided opportunities in trade, commerce, and public services, fostering the growth of a professional and mercantile middle class.

4. Economic Changes:

The Industrial Revolution in Britain had a profound impact on India. While it de-industrialized traditional Indian industries, it created opportunities in sectors like railways, tea plantations, and mining. Indian entrepreneurs, particularly from communities like the Marwaris, Parsis, and Chettiars, amassed wealth by engaging in trade and industry, forming a segment of the new elite.

5. Social and Religious Reforms:

The early 19th century witnessed a wave of reform movements, such as the Brahmo Samaj (founded by Raja Rammohan Roy) and the Arya Samaj (led by Dayananda Saraswati), which emphasized rationalism, education, and social justice. These movements inspired educated Indians to challenge orthodox practices, creating a class of progressive leaders committed to societal improvement.

6. Press and Print Media:

The growth of vernacular and English-language newspapers and journals, such as The Hindu, Amrita Bazar Patrika, and Kesari, helped shape public opinion and fostered political awareness among the middle class. These publications became platforms for debating social, economic, and political issues, amplifying the voice of the new elite.

Attitude Toward Social Reform After 1870

After 1870, the middle and elite classes became increasingly involved in addressing social issues, but their approach was shaped by their specific socio-political context. Their attitudes toward reform evolved in three broad phases:

1. Reform-Oriented Phase (1870s–1890s):

The middle class and elite were initially enthusiastic about social reform. Many were influenced by Western ideas of liberalism, rationalism, and equality, as well as the earlier reformist traditions of figures like Rammohan Roy. Their focus was on eradicating social evils such as caste discrimination, child marriage, sati, and the denial of women’s rights.

Leaders like Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar championed widow remarriage, while reformist groups like the Brahmo Samaj and Prarthana Samaj campaigned against caste oppression and emphasized education for women. Legal reforms, such as the Age of Consent Act of 1891, which raised the minimum age of marriage for girls, were often the result of their efforts.

However, this phase also witnessed resistance from orthodox groups, who perceived these reforms as an attack on Indian traditions. The reformists, while progressive, were careful to align their advocacy with Indian cultural values to avoid alienating the broader population.

2. Rise of Nationalist Concerns (1890s–1920s):

By the late 19th century, the focus of the middle and elite classes began to shift from social reform to political reform and nationalism. The formation of the Indian National Congress in 1885 provided a platform for addressing political grievances against colonial rule. Many leaders, such as Dadabhai Naoroji, Gopal Krishna Gokhale, and Bal Gangadhar Tilak, emerged from the ranks of the middle class.

Their emphasis on nationalism influenced their attitude toward social reform. They argued that political independence should take precedence over internal social issues, which could be addressed after achieving self-rule. Tilak, for instance, opposed the Age of Consent Act, viewing it as unnecessary British interference in Indian society.

While the reformist zeal did not vanish, it took a back seat to the struggle for independence. This shift reflected the growing tension between the reformist and nationalist priorities of the middle class.

3. Rise of Conservatism and Pragmatism (Post-1920s):

After 1920, the middle class and new elite became more conservative in their approach to social reform. This was partly due to the influence of leaders like Mahatma Gandhi, who emphasized a return to Indian traditions and values. Gandhi’s approach to social issues, such as untouchability, differed from earlier reformers; he sought to address these problems within the framework of Indian culture rather than adopting Western solutions.

The elite also became increasingly pragmatic, recognizing the limitations of colonial rule in implementing reforms. They focused on self-help initiatives, such as establishing schools, libraries, and cooperative societies, to uplift marginalized communities. While they supported gradual reform, their efforts were often constrained by the complexities of balancing tradition, reform, and the nationalist agenda.

Conclusion

The rise of the middle and new elite class in 19th-century India was a transformative development driven by education, economic changes, and the expansion of professional opportunities under British rule. Their attitudes toward social reform reflected their complex position as intermediaries between tradition and modernity. While their initial efforts focused on addressing social evils and promoting education, the growing nationalist sentiment after 1870 shifted their priorities toward political reform. This dual commitment to reform and nationalism defined their legacy, as they laid the groundwork for both India’s modern social institutions and the struggle for independence.

Brahmo Samaj was a powerful religious movement in India that contributed significantly to the development of contemporary India. It was founded on August 20, 1828, in Calcutta, by Raja Ram Mohan Roy and Dwarkanath Tagore as a reformation of the prevailing Brahmanism of the time (specifically Kulin practices), and it launched the Bengal Renaissance of the nineteenth century, which pioneered all religious, social, and educational advancements of the Hindu community.

Background

- In August 1828, Raja Rammohan Roy formed the Brahmo Sabha, which was eventually renamed Brahmo Samaj.

- He intended to formalize his views and goals through the Sabha.

- “Worship and devotion of the Eternal, Unsearchable, Immutable Being who is the Author and Preserver of the Universe,” the Samaj stated.

- Prayers, meditation, and Upanishad readings were to be the modes of worship, and no graven image, statue or sculpture, carving, painting, picture, portrait, or other similar object was to be permitted in Samaj structures, emphasizing the Samaj’s aversion to idolatry and useless rituals.

- The Brahmo Samaj’s long-term aim, to cleanse Hinduism and promote monotheism, was founded on reason and the Vedas and Upanishads.

- The Samaj also attempted to assimilate teachings from other religions while maintaining its emphasis on human dignity, rejection of idolatry, and condemnation of societal ills like sati.

- Rammohan Roy was opposed to the formation of a new religion.

- He merely wished to rid Hinduism of the wicked practices that had infiltrated the religion.

- Traditionalists like Raja Radhakant Deb, who founded the Dharma Sabha to combat Brahmo Samaj propaganda, were vocal in their opposition to Roy’s progressive ideals.

Features

- Polytheism and idol worship were condemned.

- It abandoned belief in heavenly avataras (incarnations).

- It rejected the idea that any text could have ultimate power over human reason and conscience.

- It maintained no firm stance on the doctrines of karma and soul transmigration, leaving individual Brahmos to believe what they wanted.

- The caste system was criticized.

- Its primary goal was to worship the everlasting God. Priesthood, ceremonies, and sacrifices were all condemned.

- It centered on prayers, meditation, and scripture reading. It thought that all religions should be together.

- It was contemporary India’s first intellectual reform movement.

- It resulted in the growth of rationality and enlightenment in India, which aided the nationalist cause indirectly.

Significance

- Many dogmas and superstitions were tackled by the Samaj in terms of social change.

- It denounced the prevalent Hindu anti-foreign travel bias.

- It campaigned for sati to be abolished, the purdah system to be abolished, child marriage and polygamy to be discouraged, widow remarriage to be encouraged, and educational opportunities to be provided.

- It also took on casteism and untouchability, but with limited success in these areas.

- The Brahmo Samaj’s impact, on the other hand, was limited to Calcutta and, at most, Bengal. It had no long-term consequences.

- It was the first intellectual reform movement in contemporary India, in which societal problems were criticized and attempts were made to eradicate them.

- It resulted in the growth of rationality and enlightenment in India, which aided the nationalist cause indirectly.

- Raja Ram Mohan Roy and his Brahmo Samaj were instrumental in bringing Indian society’s attention to the serious challenges of the day.

- It was the progenitor of all contemporary India’s social, religious, and political movements.

Brahmo Samaj and Debendranath Tagore

- When he joined the Brahmo Samaj in 1842, Maharishi Debendranath Tagore (1817–1905), father of Rabindranath Tagore and a product of the best in traditional Indian learning and Western intellect, gave the theist movement a new vitality and a defined form and structure.

- Previously, Tagore was the leader of the Tattvabodhini Sabha (established in 1839), which was dedicated to the methodical study of India’s past with a rational perspective, as well as the spread of Rammohan’s ideals through its organ Tattvabodhini Patrika in Bengali.

- Due to the informal union of the two sabhas, the Brahmo Samaj gained new energy and strength of membership.

- The Brahmo Samaj grew throughout time to include famous Rammohan followers, Derozians, and independent thinkers like Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar and Ashwini Kumar Datta.

- Tagore operated on two fronts: the Brahmo Samaj was a reformist movement inside Hinduism, and it strongly fought Christian missionaries for their critique of Hinduism and attempts at conversion outside of Hinduism.

- The revived Samaj advocated for widow remarriage, women’s education, polygamy abolition, better ryot circumstances, and temperance.

Brahmo Samaj and Keshab Chandra Sen

- When Debendranath Tagore appointed Keshab Chandra Sen (1838–84) as acharya shortly after the latter joined the Brahmo Samaj in 1858, the Brahmo Samaj witnessed a new burst of vitality.

- Outside of Bengal, branches of the Samaj were established in the United Provinces, Punjab, Bombay, Madras, and other cities, thanks to the efforts of Keshab.

- The Brahmo Samaj of India was created by Keshab and his supporters in 1866, whereas Debendranath Tagore’s Samaj became known as the Adi Brahmo Samaj.

- Keshab’s incomprehensible conduct of marrying his 13-year-old daughter to the minor Hindu Maharaja of Cooch-Behar with all the customary Hindu ceremonies sparked another division in Keshab ‘s Brahmo Samaj of India in 1878.

- Some of Keshab’s followers had begun to regard him as an incarnation, much to the chagrin of his progressive followers.

- In addition, Keshab was accused of authoritarianism.

- After 1878, Keshab’s disgruntled supporters formed the Sadharan Brahmo Samaj, a new organization.

- Ananda Mohan Bose, Sib Chandra Deb, and Umeshchandra Dutta founded the Sadharan Brahmo Samaj.

- The Brahmo teachings of faith in a Supreme being, one God, the conviction that no scripture or man is infallible, and belief in the demands of reason, truth, and morality were all restated.

- In the Madras province, several Brahmo centers have been established.

- In Punjab, the Dayal Singh Trust established Dayal Singh College in Lahore in 1910 to instill Brahmo beliefs.

Raja Ram Mohan Roy

- Raja Ram Mohan Roy was born on May 22, 1772, in Radhanagar, Bengal, to an orthodox Brahman family.

- Ram Mohan Roy had his early education in Patna, where he studied Persian and Arabic and read the Quran, Sufi mystic poets’ writings, and Arabic translations of Plato and Aristotle’s works.

- He learned Sanskrit and perused the Vedas and Upnishads in Banaras.

- Raja Ram Mohan Roy was the father of Modern India’s Renaissance and a relentless social reformer who ushered in India’s period of enlightenment and liberal reformist modernization.

- In November 1930, he set sail for England, where he would be there to prevent the repeal of the Sati Act.

- The putative Mughal Emperor of Delhi, Akbar II, bestowed the title of ‘Raja’ to Ram Mohan Roy, who was to express his concerns to the British king.

- Tagore alluded to Ram Mohan as “a dazzling light in the firmament of Indian history” in his presentation, titled “Inaugurator of the Modern Age in India.”

- Ram Mohan Roy was heavily inspired by Western contemporary ideas, emphasizing rationality and a scientific attitude to life.

- The religious and social deterioration of Ram Mohan Roy’s home Bengal was his urgent challenge.

- Instead of helping to ameliorate society’s state, he considered that religious orthodoxies had become sources of harm and detriment to social life, as well as sources of problem and befuddlement for the people.

- Tuhfat-ul-Muwahhiddin (a gift to deists), Raja Ram Mohan Roy’s first published work, was published in 1803 and revealed illogical Hindu religious beliefs and immoral practices such as believing in revelations, prophets, and miracles.

- In Calcutta, he established the Atmiya Sabha in 1814 to fight idolatry, caste rigidities, useless rituals, and other societal problems.

- Roy did a lot to spread the word about the advantages of contemporary education to his fellow people.

- While Roy’s English school taught mechanics and Voltaire’s philosophy, he backed David Hare’s attempts to create the Hindu College in 1817.

- In 1825, he founded Vedanta College, which provided education in both Indian and Western social and physical sciences.

Conclusion

India’s Brahmo Samaj is even more radical, emphasizing female education and caste disparities. The creation of the Indian Reform Association in 1870 led to the passage of the Indian Marriage Act in 1872, which legalized inter-caste marriage. Since the special relationship to Hinduism has been lost, Samaj has become more general. Along with Hinduism, Islam, Christianity, and other religions were now included.

Arya Samaj is a monotheistic Hindu reform movement in India that supports principles and practices based on the Vedas’ irrefutable authority. On 10 April 1875, the sannyasi (ascetic) Dayanand Saraswati created the samaj. Arya Samaj was the first Hindu group to practice proselytization. Since 1800, the group has also campaigned to advance the civil rights struggle in India.

Background

- Swami Dayananda Saraswati (1824-83) founded the Arya Samaj in 1875. He was a Sanskrit expert who had never studied English.

- He issued the slogan, “Back to the Vedas.”

- He was unconcerned with the Puranas. Swami learned Vedanta from a blind instructor named Swami Virajananda in Mathura. His viewpoints were similar to Ram Mohan Roy’s.

- The Arya Samaj’s social values include, among other things, God’s fatherhood and Man’s fraternity, gender equality, total justice, and fair play between man and man and country and nation.

- Intercaste marriages were also promoted, as were widow remarriages.

- Disbelief in polytheism and image worship, hostility to caste-based limitations, child marriage, opposition to the ban of sea journeys, and advocacy for female education and widow remarriage were all key programs shared by Brahmo Samaj and Arya Samaj members.

- Swami Dayananda Saraswati, like other reformers of his day, held the Vedas to be everlasting and infallible.

Features

- Believes in the infallibility of the Vedas and regards them as the ultimate source of all truth and knowledge.

- It was believed that post-Vedic books such as Puranas were to blame for the contamination of the Vedic religion.

- Opposes God’s idolatry and reincarnation idea, but supports the notion of ‘Karma’ and soul transmigration.

- Dayanand also rejected the doctrine of fate/destiny Niyati.

- Believes in a single God who does not have a physical existence.

- Rejects Brahmanical domination over Hindu spiritual and social life. Brahmins’ claim to be conduits between man and God is condemned.

- Supported the Four Varna System, however, it should be based on merit rather than birth.

- Everyone has an equal position in the spiritual and social lives of Hindus.