Medieval & Modern – 2nd Year

Paper – II (A) (Short Notes)

HISTORY OF MEDIEVAL INDIA (1526-1740)

Unit I

Language/भाषा

- The fifteenth century of the Christian era was a period of rapid political decay, contrasting with the promising developments of the previous century.

- In the fourteenth century, centralised monarchies were strong and growing, showing promise for the improvement of social and political conditions in both East and West.

- The middle class began to demand and receive a share of power in the West, while strong monarchs in the East fostered trade, expanded their dominions, and suppressed disorder.

- However, the fifteenth century saw the collapse of this centralised power, with states falling apart into fragments and disorder reappearing with greater force.

- The fifteenth century was a time of unparalleled confusion, a formless epoch lacking coherence and stability in political society.

- Despite the outward chaos, beneath the surface, the elements of modern political society were slowly beginning to take shape, ready for a more coherent structure in the future.

- The sixteenth century witnessed the beginning of this reconstruction, although it was marked by harsher, less humane conditions compared to the artistic flourishing of the fifteenth century.

- The arts of life had flourished during the fifteenth century, with small courts across India and Europe cultivating architecture and fine arts to a high degree.

- The sixteenth century, focused on large-scale projects and enterprises, lacked the delicacy and attention to detail of the previous era.

- The early sixteenth century in India and elsewhere was a period of transition, shaped by the conditions of the preceding centuries.

- In the first half of the fourteenth century, the Khiljis and Tughlaqs expanded the Delhi Sultanate‘s empire from the Sindh to the Bay of Bengal, from the Himalayas to the Krishna River.

- Despite the extensive territory, the Delhi Sultanate was often unable to maintain control over distant provinces, as frequent revolts made the monarchy resemble a continuous military campaign.

- Ala-ud-din Khilji and Muhammad bin Tughlaq were able to exercise authority, but the central control was weakened over time, leading to the decline of the empire.

- The power of provincial governors grew as they became disconnected from Delhi’s court. Many of them became independent monarchs, leading to the fragmentation of the empire.

- Timur‘s invasion in 1398 ultimately collapsed the Delhi Sultanate, ending the centralized power and marking its fall with an undeserved sense of tragedy.

- During the fifteenth century, there was no unified Hindustan, only a collection of small, independent states.

- Despite this fragmentation, the development of these small states laid the foundation for the political reconstruction that would follow.

- By the middle of the fifteenth century, these small states grouped into four major clusters of power:

- The Northern belt of Muhammadan power:

- Sindh in the south

- Multan

- Punjab, nominally a vice-royalty of Delhi, but controlled by Afghan families

- Delhi itself, claiming to be the emperor of Hindustan

- Jaunpur, ruled by the Sharqi dynasty

- Bengal, largely independent and distant from the politics of Hindustan

- The Southern Muhammadan belt:

- Gujarat, a distinct geographical entity

- Mandu in Malwa

- Khandesh

- The Deccan, under the Bahmanid dynasty

- Rajputana, consisting of resilient and independent Hindu principalities like Marwar and Mewar.

- The Hindu powers of the South, including:

- The powerful Vijayanagara Empire in the South, involved in constant warfare with northern kingdoms

- The lesser kingdom of Orissa, acting as a barrier to Bengal’s southern expansion

- The Northern belt of Muhammadan power:

- The political situation in Hindustan at the opening of the sixteenth century was shaped by these two major groups of Muhammadan powers, both threatened by Hindu forces to the south.

- The development of these kingdoms will be outlined to assess the political forces present in Hindustan as the sixteenth century begins, focusing particularly on the Afghan Kingdom of Delhi.

- The origin of the Vijayanagara Empire is obscure, emerging from the chaos caused by Muhammad bin Tughlaq‘s raids that affected the Hindu states of the south.

- The empire was established by two Kanarese feudatories, Bakka and Harihara, from the Hoysala dynasty. They built the empire on the ruins of earlier kingdoms, growing rapidly.

- Bakka reigned from 1334 to 1367, and Harihara from 1367 to 1391.

- Abd-ur-Razzak, an Arabian ambassador, visited the empire half a century after Harihara’s death and described its power and prosperity in his book Matla-us-Sadain.

- Vijayanagara was a large and populous city with a kingdom extending from Sarandip to Gulbarga, and from Bengal to Malabar—over 1000 parasangs in distance.

- The country was fertile and well-cultivated, with 300 seaports and over 1000 elephants. The army consisted of 1,100,000 men.

- The kingdom’s king held the most absolute power in Hindustan and was known as the Rai.

- The city of Vijayanagara was described as unmatched in size and structure, with seven fortified walls, each successive wall increasing in protection.

- Outside the outer wall, there was an esplanade lined with stones, preventing easy access to the city.

- The fortress was circular, situated on a hilltop, built with stone and mortar, and guarded by diligent tax collectors.

- The seventh fortress contained the royal palace, and the distance from the northern gate to the southern gate was two parasangs.

- The area between the first three walls included cultivated fields, gardens, and houses, while shops and markets crowded the spaces between the third and seventh walls.

- Four bazaars surrounded the king’s palace, with each market specialized, and flowers were vital for daily life, sold fresh in the city.

- People from all walks of life wore jewels and gilt ornaments.

- The king’s treasury was filled with molten gold and treasures, reflecting the wealth and prosperity of the kingdom.

- The political significance of the distant Vijayanagara Empire was its constant struggle with the Southern Muhammadan states, preventing any one state from gaining ascendancy and threatening the Rajputana region.

- Vijayanagara also affected the Southern Muhammadan belt, particularly the Bahmanid kingdom in the Deccan.

- The Bahmanid kingdom originated from a revolt against Delhi in 1347, led by Zafar Khan, who declared himself independent under the title of Ala-ud-din.

- The Bahmanid kingdom extended from Berar to the River Krishna and from the ocean to Indore, reaching its height under Muhammad and his successors.

- The Bahmanid kingdom faced constant struggles with Vijayanagara, and its expansion was checked by this rivalry.

- Firoz Shah (1397–1422), a notable ruler, presided over a golden age in the kingdom. He was an eccentric and talented ruler, promoting peace alongside military efforts.

- Despite its large size, the Bahmanid kingdom failed to achieve lasting political importance due to the restraining influence of Vijayanagara.

- After Mahmud Gawan‘s death in 1481, the kingdom began to fragment, splitting into several independent states:

- Berar (1484–1527)

- Ahmadnagar (1489–1633)

- Bijapur (1489–1686)

- Golconda (1512–1687)

- The fragmentation of the Bahmanid kingdom diminished Muhammadan power in Central India by the early sixteenth century.

- Khandesh, a small kingdom north of the Bahmanid realm, originated from a region governed by Firoz bin Tughlaq.

- Malik Raja Farukhi, appointed governor in the area, declared his independence and ruled wisely until his death in 1399.

- His successor, Malik Nasir, tried to intervene in the Deccan wars, but the kingdom’s resources were insufficient for success.

- Adil Khan Farrukhi (1457–1503), the last notable ruler of Khandesh, encouraged the manufacture of gold and silver cloth and fine muslins, contributing to the kingdom’s cultural development.

- Khandesh was insignificant politically but a prosperous region, reminiscent of the small states of fifteenth-century Italy, where prosperity flourished despite lack of political power.

- Khandesh’s political importance was slight, but it demonstrates how civilization and prosperity can thrive without significant political influence.

- Malwa was initially governed by a local Rajput dynasty and was annexed by Ala-ud-din Khilji in 1304.

- The kingdom gained independence in 1387 when Dilawar Khan Ghori, a Delhi nobleman, was appointed as viceroy and later declared himself king in 1401. The state lasted until 1531.

- Throughout its existence, Malwa suffered due to the rising Rajput power of Mewar, which was much stronger.

- Hoshang Shah (1405–1435), the greatest king of Malwa, managed to hold his own for a time, but towards the end of his reign, the powerful Rana Kumbha of Mewar proved irresistible.

- In 1440, Mahmud Khan Khilji, who seized the throne in 1435 as Wazir, was defeated and captured by Rana Kumbha‘s Rajputs.

- By the end of the fifteenth century, Rajputs dominated Malwa’s politics, with Hindus occupying key positions in the state. Medni Rao, a famous Rajput chieftain, acted as a kingmaker.

- Mahmud II, a puppet king, sought the help of the King of Gujarat, but Medni Rao called in Rana Singram Singh of Mewar, who captured Mahmud II in 1519 and attacked Gujarat, conquering Ahmadnagar in 1520.

- The rise of Rajput predominance in Malwa’s internal politics reflected the growing influence of the Rajput confederacy at the start of the sixteenth century.

- Gujarat, the last of the Muhammadan kingdoms of the South, had been conquered by Islam in 1196 and was under Delhi’s control until the time of Timur‘s invasion.

- Muzaffar Khan, an able administrator, was sent by Delhi to restore order in Gujarat. In 1396, he established an independent kingdom, which lasted until 1572.

- Ahmad Shah, Muzaffar’s grandson, poisoned him in 1410 and became a capable ruler, managing internal reforms and military success against Hoshang Shah of Malwa.

- Sultan Mahmud Begarha (1459–1511) ruled Gujarat during its golden age, achieving peace, encouraging trade, and expanding his dominions, notably by conquering Junagadh and Champaner.

- However, his successor, Musaafir II, faced misfortune, particularly when he tried to prevent Malwa from falling under Hindu domination, resulting in a disastrous war with Mewar.

- After Musaafir II’s death, a disputed succession led to internal troubles in Gujarat when Babur entered India on his fifth expedition.

- Rajputana, particularly Mewar, began to rise in importance at the end of the fifteenth century.

- Mewar, recognized as the premier Rajput state, reached great power under Rana Kumbha (1419–1469), who built thirty-two out of eighty-four fortresses to defend his realm.

- Rana Kumbha successfully resisted attacks from Malwa and other Muhammadan neighbors, and in 1440, he defeated the combined forces of Malwa and Gujarat.

- After Kumbha’s death in 1469, his successor Rai Mai faced conflicts with his sons Singram Singh, Prithwi Raj, and Jai Mai.

- In 1509, Singram Singh succeeded to the throne after the deaths of his brothers, bringing Mewar to the peak of its power.

- Under Singram Singh, Mewar had a powerful army with 80,000 horses, seven high-ranking rajas, 104 chieftains, and 500 war elephants.

- Singram Singh defeated forces from Delhi and Malwa, and no Hindu ruler in Hindustan could resist his might. His success marked the decline of Muslim power and the rise of the Rajput confederacy.

- Babur‘s arrival in India shifted the balance of power back towards the Muhammadans, weakening the Rajput ascendancy.

- In Sindh, the local Rajput dynasty, the Sumeras, was subdued in the thirteenth century by Islam. However, in 1336, a Rajput dynasty, the Jams, re-established independence.

- Sindh was ruled by the Jams until 1520, when it was conquered by Shah Beg Arghun, a governor from Qandahar.

- Shah Beg‘s son, Shah Husain, expanded the conquest by annexing Multan, and Sindh remained under Arghun rule until it was fully incorporated into Delhi in 1590.

- Bengal was relatively isolated and self-sufficient after its conquest by the Muhammadans, continuing to nominally submit to Delhi throughout the thirteenth century.

- Muhammad bin Tughlaq‘s reign saw Bengal revolt, and after a period of anarchy, Shams-ud-din took control in 1344 and established a dynasty that lasted until 1386.

- Following further anarchy, Raja Kans, a Hindu zarqindar, ruled until 1426.

- In 1461, Malik Andil, a former slave, ascended the throne with the support of Abyssinian mercenaries, ruling for over thirty years while maintaining order and prosperity.

- Bengal was commercial, literary, and artistic, but had little influence on the politics of Hindustan, interfering minimally with its neighbors.

- Jaunpur became independent in 1394 when Mahmud bin Tughlaq appointed his minister, the eunuch Khwaja Jahan, as governor. He declared himself independent with the title Malih-us-Sharq.

- Under his adopted son, Ibrahim Shah (1401-1440), the kingdom grew in power, maintaining its independence and focusing on architecture, industry, and agriculture.

- Mahmud Shah (1440-1457), his successor, attempted to expand his empire but was defeated by Bahlol Lodi, the Viceroy of Punjab, and forced to retreat.

- Mahmud Shah died in 1457, leading to a period of intrigue. Husain Shah, the last Sharqi king, emerged victorious.

- Husain Shah expanded his kingdom by conquering Orissa and attacking Gwalior, forcing the Raja to pay tribute. In 1473, he attacked Bahlol Lodi, but was defeated, leading to Jaunpur being annexed by Delhi in 1478.

- Delhi’s Kingdom: The Saiyid dynasty ended in 1451 with the abdication of Shah Alam. Bahlol Lodi, from the Lodi tribe, succeeded in establishing a strong rule in Delhi.

- Bahlol Lodi was a respected ruler, described as a simple man who avoided display and had personal connections with his subjects. He addressed nobles as Masnad Ali and often sought to pacify them by going to their homes and apologizing personally.

- Under Bahlol Lodi, Delhi was brought under order, and Jaunpur was re-annexed to Delhi. However, his rule was personal, relying on the support of his tribe rather than official structures.

- Sultan Bahlol’s strategy to strengthen his position involved writing letters (firman) to Afghan chiefs in Roh offering them positions in his service, leading to their mass support.

- Sultan Sikandar, Bahlol’s son, ruled from 1489-1517 but struggled to fill his father’s shoes. Despite nominal control over Delhi, Jaunpur, and Punjab, actual power lay with local vassals.

- The country was divided into jagirs (land grants) given to Afghan tribes such as the Farmulis, Lohanis, Sarwanis, and Sahu-Khails.

- Significant jagirs included Saran and Champaran held by Mian Husain, and Oudh, Ambala, and Hodhna controlled by Mian Muhammad Kala Pahar.

- Azam Humayun, a prominent jagirdar, had 45,000 horse and 700 elephants, and bought 2,000 copies of the Quran annually.

- Daulat Khan had 4,000 cavalry, and other nobles controlled significant military forces with as many as 25,000 troops among the lesser chiefs.

- The period of openhanded rule during Sultan Sikandar’s reign was later regarded as a Golden Age by historians of the Afghan dynasty during the time of the Mughal emperors.

- Historians frequently describe the peaceful, orderly administration of Sultan Sikandar’s reign, which was marked by stability and integrity.

- Sultan Sikandar ensured that every business had its appointed time and established customs were not changed. He maintained a regular process of accounting for prices and events in different districts.

- If anything seemed wrong, he conducted immediate inquiries to address it. Business during his reign was described as honest, straightforward, and peaceful.

- A new life prevailed during his reign, where people, both high and low, practiced politeness, self-respect, integrity, and devotion to religion.

- The study of belles lettres was promoted, and factory establishments were encouraged. Young nobles and soldiers were engaged in useful work.

- Nobles and soldiers were content, with each chief being appointed to the government of a district. Sikandar aimed to gain the goodwill and affection of the people.

- He put an end to war and disputes with other monarchs and nobles, ensuring peace for the sake of his officers and troops.

- Sikandar’s reign was marked by safety, enjoyment, and popularity, winning the hearts of both the high and low.

- The peaceful and prosperous period ended under Ibrahim, Sikandar’s son, who, despite being brave, was haughty, morose, and suspicious.

- Ibrahim’s tyrannical rule alienated the nobles, weakened his power, and led to active opposition from those he should have conciliated.

- His cruelties and crimes reversed the positive outcomes of his father’s reign, leading to distraction and rebellion in the kingdom.

- Panjab and Jaunpur revolted, and Ibrahim was twice defeated by the Rajputs.

- At the opening of the sixteenth century, the Muhammadan powers were weak and divided. The Rajput confederacy, led by Mewar, was on the brink of seizing the empire.

- However, the Fates intervened. Singram Singh was cheated of his prize, and the forces of Islam were re-established, while the Rajputs were doomed to endure rather than enjoy their victory.

- The key turning point was the arrival of Zahir-ud-din Muhammad, also known as Babur, who would become the Tiger and alter the course of history in India.

Babur Biography – The Founder of the Mughal Empire: Babur, the founder of the Mughal Empire and father of the Mughal emperor Humayun, was born on February 14, 1483. Recognized as one of the important Mughal rulers, he achieved remarkable victories for solidifying the dynasty’s presence in Delhi, surpassing the unsuccessful attempts of various sultanates to establish a stable rule. Under his leadership, the Mughal Empire exerted its dominance over India for almost three centuries.

Who were Mughals and Who was Babur?

Mughals belonged to the powerful branch of Turks, who were called Chagatai, named after second son of Genghis Khan, very eminent Mongol leader. The foundation of Mughal empire in India was laid by Babur, who belonged to Chagatai Turk.

Overview on Babur

| Aspect | Details |

|---|---|

| Name | Zahir-ud-Din Muhammad Babur |

| Birth | February 14, 1483 |

| Death | December 26, 1530 |

| Birthplace | Andijan, Timurid Empire (present-day Uzbekistan) |

| Reign | April 30, 1526 – December 26, 1530 |

| Title | Founder of the Mughal Empire |

| Dynasty | Timurid |

| Achievements | – Established the Mughal Empire in the Indian subcontinent |

| – Won the Battle of Panipat against Ibrahim Lodi in 1526 | |

| – Introduced Persian culture and art to India | |

| – Authored the Baburnama, an autobiography | |

| Legacy | – Laid the foundation for the Mughal Empire in India |

| – Introduced gunpowder and artillery in Indian warfare | |

| – Cultivated gardens and promoted arts and literature | |

| – Babur’s descendants ruled over India for generations | |

| Notable Battles | – Battle of Panipat (1526) |

| – Battle of Khanwa (1527) | |

| – Battle of Ghaghra (1529) |

Early Life of Babur – The Founder of the Mughal Empire

Zahir-ud-din Muhammad, also known by the names “Babur” or “Lion,” came into the world on February 14, 1483, as a member of the Timurid royal dynasty in Andijan, which is situated in present-day Uzbekistan.

- Babur’s father, Umar Sheikh Mirza, was the Emir of Ferghana, and his mother, Qutlaq Nigar Khanum, was the daughter of Moghuli King Yunus Khan.

- By the time Babur was born, the last Mongol ancestors had married into Turkic and Persian communities, blending into the local culture. Influenced significantly by Persia, they had embraced Islam, with the majority adopting the mystical Sufi-infused variant of Sunni Islam.

- In 1494, the Emir of Ferghana passed away unexpectedly, leading to 11-year-old Babur taking the throne. However, his rule faced threats, as several uncles and relatives conspired to overthrow him.

- Driven by the belief that a strong offense is the best defense, the young emir embarked on a quest for expansion. By 1497, his ambition had landed him at the gates of the storied Silk Road city of Samarkand, which he promptly conquered. However, his bold move left him exposed to internal threats. In his absence, his uncles and the lords of Andijan seized the opportunity to rise in revolt.

Babur and the Mughal Empire

At a young age, barely in his teens, Babur ascended the throne of Fergana in 1494 CE. However, his reign was short-lived. In the face of competing claims to the throne, fueled by the belief in divine rights in Genghis Khan’s lineage, Babur was ousted by his cousins.

Forced to flee his homeland of Fergana, Babur, a descendant of the legendary conqueror Timur, sought refuge in Afghanistan. Though exiled, his ambition remained undimmed. He dreamed not only of reclaiming his father’s kingdom but also of restoring and expanding the vast empire once under Timur’s dominion.

- Babar’s growing power attracted many of Lodi’s discontented subjects, including family members, military personnel, and government officials. Armed with gunpowder and the support of these allies, Babur faced Ibrahim Lodi’s vastly superior army at the First Battle of Panipat in 1526. Despite the odds, Babur’s strategic use of artillery and innovative tactics secured a decisive victory, marking a turning point in his pursuit of empire.

- With Agra as his new capital, Babur set his sights on expanding his dominion over northern India. However, his ambition met with fierce resistance from the Hindu Rajput princes, who refused to acknowledge his rule. The ensuing conflicts cast a shadow over his efforts to solidify his nascent kingdom.

- In 1527 CE, Babur achieved a pivotal victory against the Rajput princes, led by Rana Sanga, at the Battle of Khanwa. Though this triumph did not bring immediate peace, it marked a significant milestone in consolidating his burgeoning empire and weakening Rajput resistance.

Babur’s Military Conquests

Some important military conquests of Babur are as follows:

Battle of Panipat

- Prior to his full-fledged invasion, Babur conducted four reconnaissance missions to India, gaining valuable knowledge of the land and its people. This paved the way for his grander ambitions, particularly after receiving invitations from two powerful figures: Maharana Sangram Singh of Mewar and Daulat Khan Lodi, the governor of Punjab, who both sought his aid in overthrowing the ruling Sultan Ibrahim Lodi.

- The Battle of Panipat was fought on April 21, 1526, on the plains of Panipat, north of Delhi. Despite facing an overwhelming force of approximately 100,000 soldiers under Ibrahim Lodi, Babur’s army, with only 12,000 actively engaged warriors, emerged victorious in the First Battle of Panipat.

- This remarkable feat stemmed from Babur’s strategic brilliance and innovative tactics. He skillfully employed the Rumi (Ottoman) strategy of war, then a revolutionary approach, and strategically deployed his limited forces. Notably, Babur’s effective use of cannons, a cutting-edge weapon in the 16th century, proved instrumental in securing his victory.

Battle of Khanwa

- Though initially inviting Babur to aid him against Ibrahim Lodi, Rana Sanga grew wary of Babur’s ambition to remain in India. Recognizing the potential threat, Rana Sanga formed a confederacy of Rajput princes, uniting them against the foreign invader.

- The year 1527 witnessed a clash of titans at the Battle of Khanwa near Fatehpur Sikri, where Babur and the formidable Rana Sanga, a legendary warrior who had lost an arm and an eye in battle, faced off. Despite commanding a larger army, Rana Sanga was ultimately defeated by Babur’s superior weaponry and tactical prowess. This victory, more significant than the Battle of Panipat, cemented the foundation of the Mughal Empire in India.

Battle of Chanderi

- By 1527, Babur had established a foothold in India, shifting his capital from Kabul to Delhi. Chanderi, strategically located on the border of Malwa and Bundelkhand, was a crucial political and economic hub ruled by Rajput king Medini Rai. Despite being Rana Sanga’s close ally and fighting alongside him at Khanwa, Medini Rai evaded capture and escaped Rana Sanga’s control.

- Seeking to expand his empire, Babur offered Medini Rai the Shamsabad fort in exchange for Chanderi. However, the offer was rejected. Determined to conquer the city, Babur engaged in the Battle of Chanderi on January 20, 1528, facing the Rajput forces. Medini Rai remained defiant, but ultimately, Chanderi fell to Babur on January 29, 1528.

Battle of Ghaghra

Following his victory over the Rajputs, Babur decisively defeated the Afghans at the Battle of Ghagra in 1529, solidifying his control over northern India. His vast empire encompassed Kabul, Agra, Awadh, Gwalior, Bihar, and portions of Rajasthan and Punjab. Choosing Delhi as his capital, Babur officially established the Mughal Empire in India.

Rana Sangha and Babur

Rana Sangha of Mewar was one of the greatest Rajput ruler and gave one of the toughest resistance for Babur’ s extension of rule in India. On March 16, 1527, Rana Sangha along with other rulers like Marwar, Amber, Gwalior, Ajmer and Chanderi and also Sultan Mahmood Lodi, met in Kanhwa for decisive battle, aim was preventing for imposition of another foreign repression on Babur and then he took the title of “Ghazi”. On May 6, 1529, Babur met with allied Afghans of Bihar and Bengal and with this battle, Babur occupied important portion of northern India.

Babur’s Succession and End of Life

- In the autumn of 1530, illness struck Babur. Sensing his imminent demise, his brother-in-law conspired with certain nobles within the Mughal court to usurp the throne. Their ambition aimed to bypass Humayun, Babur’s designated heir and eldest son, and seize power for themselves.

- Hearing of his father’s illness, Humayun raced to Agra to claim his rightful place on the throne. Sadly, soon after his arrival, Humayun himself fell gravely ill.

- After Babur’s death at the age of 47 on December 26, 1530, Humayun inherited a shaky empire besieged by internal and external adversaries.

Achievements of Babur (1526-1530)

Babur is considered to be the founder of Mughal rule in India. Before him India was split up into many pretty independent states which were often in a state of internecine warfare. Babur’s great achievement was that he crushed the independence of these States, subjugated them and built a significant empire. All this he accomplished in a short period of four years.

- Conquest of the Punjab – Babur the king of Kabul led serious expeditions to Hindustan but it was not until the close of 1525 that he seriously embarked upon he task of conquering our country. With a large force that he possessed , he marched towards the Punjab, Daulat Khan Lodhi offered resistance , but he was ultimately defeated. Thus Punjab was conquered by Babur. Daulat Khan was pardoned and given some jagir for his maintenance.

- First Battle of Panipat( April 1526) – Babur later marched towards Delhi in order to fight against Sultan Ibrahim Lodhi. At the historic field of Panipat, the Mughals and the Afghans came face to face. Ibrahim’s army consisted of about one lakh soldiers while Babur’s forces were nearly 25,000. Even though his army was outnumbered but his cavalry and artillery led by Ustad Ali and Mustafa gave victory to Babur. Thousands of Afghans including Sultan Ibrahim Lodhi were killed in the field. Thus the Afghans suffered a crushing defeat.

- Occupation of Delhi and Agra – After the victory of Panipat , Babur sent forces under Humayun to capture Agra and he himself preceded towards Delhi to take its possession. Babur occupied Delhi very easily, then he went to Agra, which Humayun had already occupied it. Babur bestowed jagirs, grants and gifts upon all his soldiers, as well as his friends and relatives to win their faith and cooperation

- Conquests of neighbouring Afghan Territories – The victory at Panipat and the occupation of Delhi and Agra did not make Babur the master of the whole of India. There were a large number of Afghan chiefs in the territories of Sambhal, Biyana, Mewat, Dholpur, Gwalior, Rapri, Etawah, Kalpi, Kannauj and Bihar who had asserted independence in their respective territories and had fortified their strongholds. Babur encouraged his soldiers with his speech and they in return expressed their determination. Babur directed his officials to march in various directions to conquer the territories of Sambhal, Rapri, Etawah, Kannauj and Dholpur were conquered.

- Battle of Kanwah (March 1527) – The most formidable rival of Babur was Rana Sangram Singh, the Rajput chieftain of Mewar who had organised a confederacy of the Rajput chiefs and was determined to revive Hindu Padshahi in India. The Rajputs and the Mughals came face to face at Kanwah -a village a few miles from Sikri. Rana Sangram Singh was the leader of the Rajput and Afghan chiefs. Babur’s plan of the battle was almost the same as that of the battle of Panipat. Babur fought against the Rajputs and defeated them. This gave a blow to Rajput confederacy.

- Capture of Chanderi (January 1528) – There was no doubt the Rajputs had suffered a miserable defeat at Kanwah but still they were not completely crushed. Medni Rao of Chanderi was a powerful Rajput chief who by virtue of his strength played the the role of King maker in Malwa. In January 1528 Babur personally marched towards Chanderi with a large force. Medini Rao shut himself up in the fort with 5000 men. Babur with full determination attacked the fort of Chanderi. The Rajiputs offered tough resistance , the Rajput women even performed Jauhar. Still the fort was captured by Babur on January 29, 1528. Soon after this Rana Sangram Singh died and his death gave a fatal blow to Rajput power. Having captured Chanderi Babur proceeded to subdue the rebellious Afghan chiefs.

- Battle of Ghagra (May 1529) – Mahmud Lodhi the brother of late Ibrahim had become the master of Bihar and the adjoining territories towards the east. Babur sent his son Askari with a large force against him and soon afterwards followed himself. On his way Babur procured the submission of many Afghan chiefs. Disserted by many of his supporters and feeling himself too weak, Mahmud took shelter with Nusrat Shah of Bengal. Babur now marched towards Bengal and on 6th of My 1529 he inflicted a crushing defeat upon the Afghans at the battle of Ghagra. After this Babur concluded a treaty with Nusrat Shah by which each party agreed to respect the sovereignty of the other. Nusrat Shah also promised not to give shelter to the enemies of Babur.

Thus Babur conquered quite a a large portion of Hindustan extending from the Indus to Bihar and from Himalayas to Gwalior and Chanderi. He ruled over it, administered it and thereby laid the foundation of the Mughal empire. But unfortunately Babur could not get time to take the roots of the empire deep into the soil of our country for the inevitable death took him away on 26th December, 1530.

Conclusion

Despite his brief reign of four years, Babur left a lasting legacy in India. His profound love for nature sparked the creation of exquisite gardens, a tradition that became an integral element of Mughal architecture in the years to come. In 1529, Babur decisively defeated the combined forces of Afghans and Mahmud Lodi, effectively crippling resistance and securing the survival of the fledgling Mughal dynasty. His conquests significantly expanded the empire’s boundaries, encompassing a vast region stretching from Kabul in the west to Ghagra in the east and from the Himalayas in the north to Gwalior in the south.

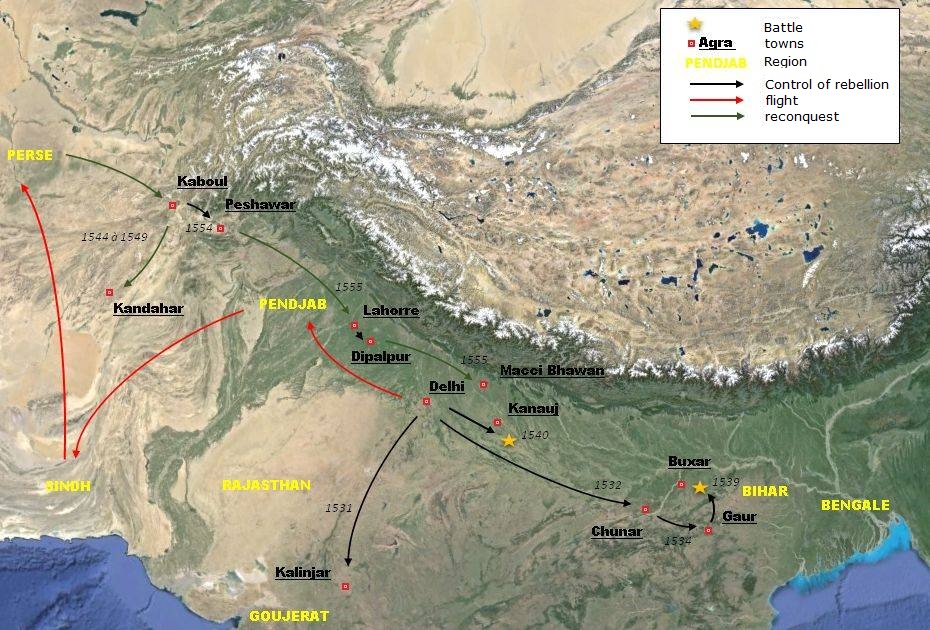

- After the sudden demise of Babur, he was succeeded by his oldest son Humayun. Humayun is probably the only king in the history of India whose rule included two spells, one from 1530-1540 and the other from 1555 to 1556 after his fifteen years’ of exile from India.

- Humayun, literally means ‘fortunate’ but through most part of his life, he remained ‘unfortunate’. He inherited a rich-legacy of difficulties but he made it richer by his own blunders. As a ruler he lacked foresight and was incapable of taking a long term view of political and military problems. He faced many challenges in firmly establishing the Mughal empire.

- Due to untimely death of Babur, the administration had not yet been consolidated. Babur spent almost his time in wars and could not take suitable steps to organize the administration of the territories he conquered.

- The Mughal army was a heterogeneous body of several races – Chaghatais, Uzbeks, Mughals, Persian, Afghans and Hindustanis, etc. Such an army could be kept under control and disciplined only under the leadership of a capable, dashing and inspiring commander like Babur. Humayun was too weak for this purpose.

- The finances were precarious. After getting enormous wealth from the royal treasuries of Delhi and Ajmer, Babur distributed it so lavishly among his soldiers and nobles that very little were left for Humayun to conduct the affairs of his administration. In due course, these nobles became very powerful and they posed a great threat to the stability of the Mughal Empire.

- Babur did not urge Humayun to follow the Timurid tradition of dividing the empire among all the brothers as the Empire itself was in infancy. However, on his deathbed, he had counselled him to be kind and forgiving towards his three brothers. Humayun made Kamran the ruler of Kabul and Kandhar, Askari, the ruler of Rohilkhand and Hindal, the ruler of Mewat (comprising the modern territories of Alwar, Mathura and Gurgaon).

- Thus, his sphere of influence and power was reduced. Moreover, there was ungratefulness and incompetency of Humayun’s brothers.

Retreat and Rise of the Afghans

- Even after the Battle of Ghaghra, the Afghans had not been subdued, and were nursing the hope of expelling the Mughals. The Afghans who were ruling Delhi a few years back still had ambition to capture power again.

- Bahadur Shah, the ruler of Gujarat, was also an Afghan. He was also ambitious of the throne of Delhi. But the most important and powerful Afghan, who later drove away Humayun, was Sher Shah in the East. Hence it was Bahadur Shah in the West and Sher Shah in the East which hemmed in Humayun and he fought many battles with them.

- Humayun failed to estimate the growing power of Sher Shah Suri. He should not have accepted the half-hearted submission of Sher Shah when Humayun besieged the Chunar fort. In fact he should have nipped him in the bud.

- But Humayun lacked resolution and sustained energy, foresight and quick grasp of situation. In the Battle of Kannauj, he made blunders in choosing a low land for encampment and for remaining inactive before the enemy for two months.

- Thus, many of the troubles of Humayun were of his own making. He did not understand the nature of Afghan power. Due to existence of large numbers of Afghan tribes scattered over north India, the Afghans could always unite under a capable leader and pose a challenge. Without winning over the local ruler and zamindars to his side, the Mughals were bound to remain numerically inferior.

- Sher Khan was superior to Humayan in preparing and planning battles and in fighting the enemy. Sher Shah had more experience, more knowledge of strategies, and more organizing capacity. He never missed an opportunity and could use wily tricks and crafty means to conquer the enemy.

- Even in the case of Bahadur Shah, Humayun lacked military strategy and quick decision making thus kept losing opportunities. Rajputs requested him for assistance and entreated him to attack Bahadur Shah at Chittor. However, Humayun wasted time, thus allowing his opponents to make adequate preparations and to consolidate their positions.

- But, still the Gujarat Campaign was not a complete failure. While it did not add to the Mughal territories, it destroyed forever the threat posed to the Mughals by Bahadur Shah. Soon after, Bahadur Shah drowned in a scuffle with the Portuguese on board one of their ships.

- During Humayun’s Malwa Campaign, Sher Shah had further strengthened his position and became unquestioned master of Bihar with widespread support of the Afghans. Soon after, he acquired Bengal also. But Humayun was not prepared to leave Bengal to Sher Khan as it was the land of gold, rich in manufactures, and a centre for foreign trade. Humayun’s march to Bengal, was the prelude to the disaster which overtook his army at Chausa almost a year later. His brother Hindal rebelled against him and Humayun was cut off from all news, supplies and reinforcements.

- Then Humayun showed bad generalship and political sense by crossing the Karmnasa river and being very weakly positioned against Sher Khan’s onslaught. Humayun barely escaped with his life from the battlefield, swimming across the river with the help of a water carrier. This defeat in battle of Chausa greatly weakened his position. Moreover, again in the Battle of Kannauj, Humayun was defeated.

This battle decided the issue between Sher Shah and the Mughals. Sher Shah became the new ruler of North India and ordered Humayun to leave India.

Humayun’s Later Life

- After ruling for ten years, Humayun was forced to spend 15 years out of India. Humayun became a prince without a kingdom. He wandered in Sindh and its neighbouring regions for the next two and a half years, hatching various schemes to regain his kingdom. But neither the ruler of Sindh or Marwar nor his brothers were willing to help him.

Worse, his own brothers turned against him, and tried to have him killed or imprisoned. Ultimately, Humayun took shelter at the court of Iranian King of Safavid Dynasty, and with his help recaputured Qandhar and Kabul from Kamran in 1545. - Although not as vigorous as Babur, Humayun showed himself to be a competent general and politician till his ill-conceived Bengal campaign. In 1555, following the breakup of the Sur empire, he was able to recover Delhi.

- Humayun’s life was a romantic one. He went from riches to rags, and again from rags to riches. It is not doing justice to Humayun when it is said that he was a failure.

- True, he failed against Sher Shah but after Sher Shah’s death, he seized every opportunity to come to power. But his spirit was not subdued. Even after 15 years of exile, he could recapture his throne of Delhi and restore the power and prestige of the Mughals. However, he did not live long to enjoy the fruits of victory and died from a fall from the first floor of the library building in his fort in Delhi within six months of coming to power.

Nasir al-Din Muhammad also known as Humayun, was the second emperor of the Mughal Empire, ruling over territory that is now Eastern Afghanistan, Pakistan, Northern India, and Bangladesh from 1530 to 1540 and again from 1555 to 1556. Humayun succeeded his father to the throne of Delhi and the Mughal lands in the Indian subcontinent in December 1530. When Humayun came to power at the age of 22, he was an inexperienced monarch. Humayun’s worst enemies were the Afghans. They were the masters of Delhi only a few years ago, and they have not given up their desire to reclaim it.

Causes of Conflict

- Babur had taken Delhi’s throne from the Afghans. As a result, they were hostile to Humayun.

- Sher Shah Suri was an Afghan as well.

- Sher Shah cemented his authority in Bihar while Humayun was busy battling Bahadur Shah of Gujarat.

- Sher Shah was the proud owner of Chunar’s stronghold and had united the majority of the Afghan nobles under his banner.

- He assaulted Bengal twice and demanded a large sum of money from the ruler.

- Humayun knew that subduing Sher Shah was required.

Afghan Struggle

Humayun and Sher Shah met with each other three times, in Chunar, Chausa, and Kannauj.

Siege of Chunar (1532)

- Humayun was frightened by Sher Shah’s success in Bengal and Bihar.

- Instead of heading straight to Bengal, where he could have enlisted the support of Bengal’s monarch, Humayun spent six months besieging the fort of Chunar in Bihar, which was under Sher Shah’s control.

- Sher Shah made a fully voluntary submission after seeing his weakness, and Humayun captured the fort of Chunar.

Battle of Chausa (1539)

- For approximately six years, there appeared to be no major confrontations between Sher Shah and Humayun. Sher Shah’s position grew significantly during this time.

- Humayun travelled to Bengal on the behest of the ruler of Bengal and spent around eight months there in 1538.

- Sher Shah conquered a number of cities over these eight months, including Banaras, Sambhal, and others. Meanwhile, Hindal, Humayun’s brother, declared himself Emperor of Delhi.

- Humayun chose to return from Bengal to Agra. Sher Shah, however, blocked his way at Chausa, the Bihar-Uttar Pradesh border.

- For three months, the two armies stood facing each other. This created tension between both armies. Mughals were tricked.

- Sher Shah devised a strategy at this point. He stated that he was going up against a tribal chief who had been disobeying him.

- In the early hours of June 26, 1539, after marching a few miles in that direction, he returned unexpectedly in the night and attacked Humayun’s army from three sides. Humayun was wounded and lost the battle.

- To save his life, he threw his horse into a river and was saved from drowning by a water carrier. As a result, Sher Shah Suri declared himself a Sultan and captured West Bengal.

Battle of Kannauj (1540)

- Humayun arrived in Agra after his defeat at Chausa and sought support from his brothers. All of the brothers, however, were unable to unite.

- Humayun gathered a large army, primarily made up of young recruits, and marched towards Kannauj.

- Sher Shah has already set up camp in Kannauj and won this battle. The success of Sher Shah was crucial.

- Humayun escaped and pushed his way to Agra.

- As a result, Humayun had to spend roughly fifteen years in exile after his defeat at Kannauj, from 1540 to 1554.

Causes of Defeat of Humayun and Sher Shah’s Success

- Humayun’s inability to realize the essence of Afghan authority and lack of organizational skills.

- His brothers were unhelpful and Humayun was unable to maintain consistent effort.

- Sher Shah’s diplomatic capitulation and Humayun’s release of Chunar.

- Humayun wasted most of the time in celebration and procrastination.

- Sher Shah launched an unexpected attack against Humayun’s troops in Kannauj.

- Humayun’s army lacked command cohesion.

Conclusion

Humayun and Afghans under the command of Sher Shah Suri fought the Second Afghan-Mughal war (1532-1540). Sher Shah Suri was a prominent Afghan nobleman who desired to take control of Delhi and Agra. He consolidated his stronghold in Bihar and Bengal while Humayun was engaged in conquering Gujarat. He also cut off Humayun’s connection to Agra. Sher Shah defeated the Mughal army in the Battle of Kanauj later that year. In 1540, the Afghans won and all Mughals were banished from India. Sher Shah Suri claimed to be the king of Delhi and Agra.

Humayun’s early life

As the story goes, Humayun fell ill and his father Babur prayed for his recovery and transfer his illness to him. His prayer was granted. Humayun recovered, Babur fell ill and died soon.

After the death of his father, Humayun ascended the throne of Delhi. Nasir-ud-Din Muhammad Humayun who is popularly known as Humayun was the eldest son of Babur. Kamran, Askari and Hindal were his step brothers. He learnt Turki, Arabic and Persian. He worked as governor of a province in Kabul.

He took part in the battles of Panipat and Khanwa. He looked after the administration of Hissar, Firuza and Sambhal. He was nominated by Babur as his successor. Humayun is probably the only king in the history of India whose rule included two spells, one from 1530-40 and the other in 1555-56 after his fifteen years’ exile from India. Humayun, literally meaning ‘fortunate’ but through most part of his life, he remained ‘unfortunate’. He is again the only king who on the advice of his father treated his half-brothers in real brotherly affection but without any reciprocal response from them rather betrayal from one.

Early difficulties faced by Humayun and Babur’s Legacy

The throne inherited by Humayun was full of thorns. He had to face several difficulties right from his accession. Among the major factors which contributed to his difficulties and problems were the legacy of Babur’s will, the unfriendly treatment of his brothers and relatives and lastly, the hostile attitude of the Afghans and the Rajput’s.

Babur had entered the country as a stranger and spoiler. He had defeated the armies and broken the power of the reigning dynasty i.e. the Lodis. The only hold which he and the Mughals had upon the people of India was military force. Babur had not created a strong administrative machinery to control such a vast empire.

1. Division of empire according to Babur’s will

Humayun very faithfully implemented the will of his father. He treated all his young step brothers very kindly. He made Kamran the ruler of Kabul and Kandhar, Askari, the ruler of Rohilkhand and Hindal, the ruler of Mewat (comprising the modern territories of Alwar, Mathura and Gurgaon). Thus his sphere of influence and power was reduced. This division weakened the unity of the empire.

2. Ungratefulness and incompetency of Humayun’s brothers

Kamran, after taking Kabul and Kandhar, took Punjab forcibly. Hindal too declared himself emperor. Askari lost some part of the area allotted to him. All these actions had an adverse effect on Humayun.

3. Hostile attitude of Humayun’s own relatives

Mutual conspiracies and jealousies of Humayun’s relatives created several problems for him. Muhammad Jama Mirza, a powerful noble and the husband of Humayun’s sister, Muhammad Mehdi Khwaja, Babur’s brother-in law, and Muhammad Sultan Mirza, Humayun’s cousin were quite powerful and ambitious. They created several problems for him.

4. Lack of suitable administrative machinery

Babur spent almost his time in wars and could not take suitable steps to organize the administration of the territories he conquered.

5. Want of a well-integrated and unified army

The Mughal army was a heterogeneous body of several races—Chaghatais, Uzbeks, Mughals, Persian, Afghans and Hindustanis, etc. Such an army could be kept under control and disciplined only under the leadership of a capable, dashing and inspiring commander like Babur. Humayun was too weak for this purpose.

6. Babur’s Distribution of Jagirs

Babur’s nobles and soldiers had rendered great assistance to him in his conquests. Therefore, in order to please them Babur gave them Jagirs liberally, In due course these nobles became very powerful and they posed a great threat to the stability of the Mughal empire.

7. Paucity of funds

After getting enormous wealth from the royal treasuries of Delhi and Ajmer, Babur distributed it so lavishly among his soldiers and nobles that very little were left for Humayun to conduct the affairs of his administration.

8. Hostility of the Afghans

The Afghans who were ruling Delhi a few years back still had ambition to capture power again. Bahadur Shah, the ruler of Gujarat, was also an Afghan. He was also ambitious of the throne of Delhi. But the most important and powerful Afghan, who later drove away Humayun, was Sher Shah.

9. Belied Rajput’s hopes

Though the power of the Rajput’s had been weakened by Babur, yet they cherished some hopes of recovering their lost power and territories.

Humayun’s own responsibility for most of his Difficulties

As a ruler he lacked foresight and was incapable of taking a long term view of political and military problems. He was not a good judge of men and circumstances. He lacked sustained effort and after a victory he would fritter away his energy in revelry.

No doubt, he inherited a rich-legacy of difficulties but he made it richer by his own blunders. His lethargy was chronic. Though beset with dangers and better enemies all around, he did not develop the ‘Killer’s instinct’. He was daring as a soldier but not cautious as a general. He failed to pounce upon opportunities as well as upon his enemies in time. In the words of Lane-poole, “Humayun’s greatest enemy was he himself.”

1. Weak personality

Humayun lacked resolution and sustained energy, foresight and quick grasp of situation. “He revelled at the table when he ought to have been in the saddle”. He was slow to understand men, slow to grasp golden opportunities, slow to decide, slow to win a battle. As observed by Lane-poole, “He lacked character and resolution. He was incapable of sustained efforts after a moment of triumph and would busy himself in his ‘harem’ and dream away the precious hour in the opium eaters’ paradise while his enemies were thundering at his gate.

2. Underestimating Sher Shah’s strength

He failed to estimate the growing power of Sher Shah Suri. He should not have accepted the halfhearted submission of Sher Shah at chunar. In fact he should have nipped him in the bud.

3. Negative response to Rajput’s’ request

He should have given a positive response to the request of the Rajput’s and attacked Bahadur Shah of Gujarat at Chittor and should have completely crushed his power.

4. Lack of military strategies

Humayun did not attack his strong opponents at the appropriate time. Instead of rushing to Chittor to attack Bahadur Shah, he wasted time in festivities at Mandu. Likewise, instead of punishing the rebels in Bihar, he spent several months on his way in besieging minor places. All this gave time to his adversaries to make adequate preparations and to consolidate their positions.

5. Defensive attitude

After his defeat at Chausa, he always remained on the defensive. He did not attempt to recapture the territory.

6. Wrong choice of site

In the battle of Kanauj, he made blunders in choosing a low land for encampment and for remaining inactive before the enemy for two months.

7. Leniency to his enemies

He pardoned again and again those who revolted against him. This he did not only in the case of Kamran but also in the case of Mohammad Zaman Mirza.

8. Sher Shah – more capable

It must be admitted that he was no match for Sher Khan who was in every respect superior to him in preparing and planning battles and in fighting the enemy. Sher Shah had more experience, more knowledge of strategies, more organizing capacity. He never missed an opportunity and could use wily tricks and crafty means to conquer the enemy while Humayun could not do anything, which did not beloved a king as well as gentleman, and refined person.

Success at the end

It is not doing justice to Humayun when it is said that he was a failure. True he failed against Sher Shah but after his death, he seized every opportunity to come to power. But his spirit was not subdued. Even after 15 years of exile he could recapture his throne of Delhi and restore the power and prestige of the Mughals. “He went from riches to rags and again from rags to riches.”

In his personal life, Humayun was an obedient son, lovable husband, affectionate father and a good relative. He was generous and attached in temperament, cultured and fond of learning. He was the lover of humanity and the model of a gentleman.

Humayun possessed a dominant will. Dr. S. Roy has rightly commented, “With all his weaknesses and failings, Humayun has a significant place in Indian history which is not, perhaps, always duly appreciated. The well- timed restoration of the Mughal power was a real achievement which paved the way, for the splendid imperialism of Akbar.”

After ruling for ten years, he was forced to spend 15 years out of India. When he was able to recover Delhi, he could hardly enjoy the fruits of his victory, as within six months, he fell down from the stairs of his library in Delhi fort and died.

Nasir al-Din Muhammad also known as Humayun, was the second emperor of the Mughal Empire, ruling over territory that is now Eastern Afghanistan, Pakistan, Northern India, and Bangladesh from 1530 to 1540 and again from 1555 to 1556. Humayun succeeded his father to the throne of Delhi and the Mughal lands in the Indian subcontinent in December 1530. When Humayun came to power at the age of 22, he was an inexperienced monarch. Humayun’s worst enemies were the Afghans. They were the masters of Delhi only a few years ago, and they have not given up their desire to reclaim it.

Humayun and Afghans – Causes of Conflict

- Babur had taken Delhi’s throne from the Afghans. As a result, they were hostile to Humayun.

- Sher Shah Suri was an Afghan as well.

- Sher Shah cemented his authority in Bihar while Humayun was busy battling Bahadur Shah of Gujarat.

- Sher Shah was the proud owner of Chunar’s stronghold and had united the majority of the Afghan nobles under his banner.

- He assaulted Bengal twice and demanded a large sum of money from the ruler.

- Humayun knew that subduing Sher Shah was required.

Humayun – Afghan Struggle

Humayun and Sher Shah met with each other three times, in Chunar, Chausa, and Kannauj.

Siege of Chunar (1532)

- Humayun was frightened by Sher Shah’s success in Bengal and Bihar.

- Instead of heading straight to Bengal, where he could have enlisted the support of Bengal’s monarch, Humayun spent six months besieging the fort of Chunar in Bihar, which was under Sher Shah’s control.

- Sher Shah made a fully voluntary submission after seeing his weakness, and Humayun captured the fort of Chunar.

Battle of Chausa (1539)

- For approximately six years, there appeared to be no major confrontations between Sher Shah and Humayun. Sher Shah’s position grew significantly during this time.

- Humayun travelled to Bengal on the behest of the ruler of Bengal and spent around eight months there in 1538.

- Sher Shah conquered a number of cities over these eight months, including Banaras, Sambhal, and others. Meanwhile, Hindal, Humayun’s brother, declared himself Emperor of Delhi.

- Humayun chose to return from Bengal to Agra. Sher Shah, however, blocked his way at Chausa, the Bihar-Uttar Pradesh border.

- For three months, the two armies stood facing each other. This created tension between both armies. Mughals were tricked.

- Sher Shah devised a strategy at this point. He stated that he was going up against a tribal chief who had been disobeying him.

- In the early hours of June 26, 1539, after marching a few miles in that direction, he returned unexpectedly in the night and attacked Humayun’s army from three sides. Humayun was wounded and lost the battle.

- To save his life, he threw his horse into a river and was saved from drowning by a water carrier. As a result, Sher Shah Suri declared himself a Sultan and captured West Bengal.

Battle of Kannauj (1540)

- Humayun arrived in Agra after his defeat at Chausa and sought support from his brothers. All of the brothers, however, were unable to unite.

- Humayun gathered a large army, primarily made up of young recruits, and marched towards Kannauj.

- Sher Shah has already set up camp in Kannauj and won this battle. The success of Sher Shah was crucial.

- Humayun escaped and pushed his way to Agra.

- As a result, Humayun had to spend roughly fifteen years in exile after his defeat at Kannauj, from 1540 to 1554.

Causes of Defeat of Humayun and Sher Shah’s Success

- Humayun’s inability to realize the essence of Afghan authority and lack of organizational skills.

- His brothers were unhelpful and Humayun was unable to maintain consistent effort.

- Sher Shah’s diplomatic capitulation and Humayun’s release of Chunar.

- Humayun wasted most of the time in celebration and procrastination.

- Sher Shah launched an unexpected attack against Humayun’s troops in Kannauj.

- Humayun’s army lacked command cohesion.

Conclusion

Humayun and Afghans under the command of Sher Shah Suri fought the Second Afghan-Mughal war (1532-1540). Sher Shah Suri was a prominent Afghan nobleman who desired to take control of Delhi and Agra. He consolidated his stronghold in Bihar and Bengal while Humayun was engaged in conquering Gujarat. He also cut off Humayun’s connection to Agra. Sher Shah defeated the Mughal army in the Battle of Kanauj later that year. In 1540, the Afghans won and all Mughals were banished from India. Sher Shah Suri claimed to be the king of Delhi and Agra.

Sher Shah Suri founded the Suri dynasty and he originated from Afghanistan who took control over the Mughal Empire in the year 1540 after defeating the second Mughal emperor Humayun. He had a significant contribution in the suri dynasty and he introduced a long-term bureaucracy in the calculated revenue system. He made a systematic relationship between the ruling king and the people. Sher Shah Suri captured Delhi to expand his sultanate and Gwalior and Malwa. He had a great contribution to the suri dynasty and after his death he was buried in Sasaram. His tomb was very significant in the sultanate’s history as well.

Overview of Sher Shah Suri

Sher shah suri was the founder of the Suri dynasty after defeating the Mughal emperor Humayunh in 1540. His capital was in Sasaram in the modern day of Bihar. He was the person who introduced the “rupee” in the calculated system of revenue. Sher Shah Suri was very brave and he ruled over Bihar. He changed some ruling posts and introduced many posts which have been divided into the Sarkars post. Sher Shah Suri was one of the greatest leader among the muslim rulers of india. He brought some private posts such as administrative army and taxation posts. He built roads, house rents and many wellbeing things for the people. He was known for introducing the postal for the people of the Indian continent.

Salient Features of Sher Shah’s General Administration

Sher Shah, by the dint of his military skill, daring acts, great courage and resourcefulness not only established a mighty empire.

But also by his shrewd capacity for organizing, unique forethought and intimate knowledge of administration, made necessary arrangements for smooth and efficient administration and controlling the coveted empire.

Some of the salient features of his administration are given below:

A benevolent despot

Dr. Ishwar Prasad has rightly observed, “The Government of Sher Shah, though autocratic was enlightened and vigorous.” Sher Shah himself used to say, “It behoves the great to be always active.” And he himself adhered to this maxim. According to Crooke, “He was the first Musalman ruler who studied the good of the people.” Sher Shah believed, “Tyranny is unlawful in everyone, especially in a sovereign who is the guardian of his public.”

Advice of the council of Ministers

Sher Shah had a number of ministers to assist him in his administrative work. The ministers looked after their respective departments. Their appointment and dismissal was at his discretion.

Provincial administration

Historians have differed on the issue of Sher Shah’s provincial administration. While Qanungo has opined that there was no administrative unit called ‘Suba’ or ‘Iqta’, Dr. P. Saran states that there were ‘Subas’ where military officers were appointed by She Shah.

The entire kingdom was divided into provinces. Some provinces were very large and others small. There was no uniformity with regard to their income, size and administration. In the sensitive provinces like Lahore, Multan and Malwa, military governors looked after the administration. On the other hand, the province of Bengal was administered by a civilian.

(a) Sarkars:

A province was divided into a number of Sarkars (Districts). In all there were 47 districts. There were two chief officers in every district. The one chief Shiqdar or Shiqdar-i- Shiqdaran was a military officer. He maintained peace and order in the district, helped in the collection of revenue and other taxes and also supervised the work of his subordinate officers called Shiqdars.

The other officer was called the chief Munsif or Munsif- i-Muinsfan. He was primarily a judicial officer who looked after justice in the district. He also looked after the working of his subordinate judicial officers in the parganas. These two officers were helped by a number of junior officers and other subordinates in carrying out their duties.

(b) Parganas:

Each Sarkar was divided into small units called the parganas and each Pargana was further subdivided into a number of villages. Like the Sarkars, there were two chief officers called a Shiqdar (military officer) and Munsif (civilian judge) who were assisted by other staff in the discharge-of their duties.

(c) Villages:

A village was the smallest self-sufficient unit, administered by village panchayats. Sher Shah introduced the system of transferring officers of the Sarkars and the Paragans every two or three years so that they may not develop vested interest, the root cause of corruption.

Sources of income

Important sources of income were:

- Land revenue

- (Taxes on the transportation of raw and finished products

- (The royal mint

- Confiscation of the unclaimed property

- Tributes from the rajas, nawabs jagirdars, etc.

- Gifts from the foreign travellers

- Salt tax

- Jaziya on the Hindus

- One-fifth of the Kham (booty).

Land and revenue administration

The revenue administration of Sher Shah has been regarded as one of the best during the medieval period.

Important features of the revenue administration were as under:

- Land for the purpose of revenue was divided into three categories on the basis of production—good, average and bad.

- Generally land revenue was one-third of the produce, but could be paid both in cash and kind.

- The land of each cultivator was measured according to a uniform standard and its quality was ascertained.

- Lease deeds (pathas) were drawn between the farmers and the government. The area, the type of the soil, and the rates of land revenue were recorded on the lease deeds which were got signed by the farmers. The deeds confirmed the rights of the farmers on the lands.

- Land revenue was remitted on poor crops.

- Financial assistance (Taqavi loans) was granted to the farmers when needed by them.

- The Sultan had ordered that while fixing the land revenue, the peasants should be treated with generosity but once settled they were asked to pay their revenue regularly.

In the words of Qanungo, “The land revenue administration of Sher Shah was a valuable heritage for the Mughals. He tried to levy the land revenue in accordance with the income of the peasants. The British adopted this system.”

Welfare of farmers

Sher Shah was very particular about the welfare of the peasants. He used to say, “If I oppress them they will abandon their villages and the country will be mined and deserted.”

Law and order

The most important contribution of Sher Shah was the reestablishment of law and order across the length and breadth of the empire. Dacoits and robbers were dealt with very sternly. It has been stated by several historians that during the reign of Sher Shah, an old woman might place a basket of golden ornaments on her head and go on a journey without any fear. No thief or robber would come near her for fear of punishment.

Local responsibility for theft

The local people or the head (Mukhiya) of the village was responsible for the safety of the people of the area and the travellers. It was the responsibility of the village Panchayat or the local people to produce the culprit or to pay for the stolen goods. In case the local officers of the village failed to trace the murderer, the headman was given the penalty of death. This method helped to wipe off thefts, robberies and murders.

Fair judicial administration

Sher Shah used to say and act upon it, “Justice is the most excellent of religious rites.” No one could escape punishment on account of high status.

The Sultan was the highest judicial authority in the state. Sher Shah held his court every Wednesday in the evening. Next to him was the chief Qazi who was the head of the department of justice.

There were subordinate Qazis in every district and in all important cities. The criminal law was severe. The offenders were punished by fines, flogging, imprisonment and even cutting of the limbs.

Efficient Espionage System

Sher Shah’s efficient administrative system largely depended upon his well-organised espionage system. The king kept himself posted with the minutest happening in his kingdom. The nobles were afraid of indulging in activities not conducive to the stability of the rule of the Sultan. Even the rates prevailing in the mandis were made available to the king. Spies were kept at all important places and at all importantt offices.

Well organised ‘dak’ system

The saraits were also used as Dak Chaukis. Two horses were kept at every sarai so that the news-carriers could get fresh horses at short intervals to maintain speed.

Currency

The ratio of exchange between the Dam and rupee was fixed at 64 to 1. The same coin-rupee ratio served the basis of the currency during the Mughal and British periods. Earlier there was no fixed ratio among so many coins of various metal alloys. He abolished the old and mixed metal currency. He issued fine coins of gold, silver and copper of uniform standard.

Network of roads

Sher Shah constructed a network of roads connecting important parts of his empire within his capital. He repaired old roads.

Sher Shah constructed the following four highways:

- Sadak-e-Azam (Grand Trunk Road) starting from Sonargaon in Eastern Bengal passing through Agra, Delhi and Lahore and terminating at Peshawar, covering a distance of about 3,000 km;

- From Agra to Jodhpur and the Chittor fort;

- From Agra to Burhanpur;

- From Lahore to Multan.

Prosperous Trade and Commerce

Law and order in the kingdom, protection of traders on roads, issue of new currency and the simplication of taxes helped in the promotion of trade and commerce. Trade tax was collected only at two places. One, where the goods entered the territory of his empire and the other where the goods were sold. All other internal trade taxes were abolished.

Sarais

About 1700 sarais were constructed on both sides of the roads. Each sarai had separate rooms for the Hindus and the Muslims. Each sarai had a well and a mosque. These sarais also served as dak Chaukis. In view of the special significance of these sarais, they were called as veritable arteries of the empire.”

Beautiful buildings

Sher Shah built the following buildings:

- Mausoleum of Sher Shah at Sasaram in Bihar

- Fort of Rohtasgarh on the banks of the river Jhelum in the north-west.

- Purana Qila at New Delhi,

- Mosque in the Purana Qila.

The Mausoleum of Sher Shah built in the midst of a lake on a lofty plinth, ranks among the most beautiful buildings in India.

Promotion of education

For the education of the Muslims, a Maktab was attached to every mosque for imparting elementary education and teaching Arabic and Persian. Madrasas were set up for higher education. Endowments and grants were given to educational institutions. Provision was also made for scholarships on the basis of merit.

Introduction

On 30th October 1553, Islam Shah died and the battle of Panipat, in which the Afghans were decisively defeated, took place on 5 November 1556. This three-year period, from Islam Shah’s death to the defeat at the hands of the Mughals, is regarded as the period of disintegration of the Sur Empire, which Sher Shah and Islam Shah had built with such great effort.

Disintegration was brought about by two processes which were continuing simultaneously. One was the process of the growing Mughal pressure against the Surs.

Disintegration was triggered by two concurrent processes. One factor was the increasing Mughal pressure on the Surs. Mughal military pressure on the Surs began in December 1554. In fact, Humayun set out from Kabul in November 1554 with the intention of re-occupying Northern India. The news he received in Kabul about the growing factional tussle within the Sur Empire after Islam Shah’s death encouraged him to embark on this expedition. On 24 February 1555, Humayun occupied Lahore.

On 22nd June 1555, he defeated the Afghan forces led by Ibrahim Sur in the Battle of Sirhind.

Side by side with this was the second process the growing situation of the factional tussle within the Sur Empire which tended to get accentuated as the Mughal pressure against them mounted. In this discussion, we will be focusing on this second process.

Causes for the Decline of Sur Dynasty

It shall be pertinent at this stage to examine the question as to why the second Afghan Empire so ably founded by Sher Shah did not last long after him and disintegrated within fifteen years of his departure. Some of the causes which contributed to the decline of the Sur Dynasty where as follows:

1. Factional Fights and Rivalries

For having a proper understanding of the role that was played by different nobles and princes in this tussle, we should first of all have a broad view of the distribution of important military commanders in the Sur empire at the time of Islam Shah’s death. One knows that towards the last few years of Islam Shah’s reign he had almost totally displaced the senior nobles of Sher Shah’s time by his own favorites in high positions and important military commands. In fact when Islam Shah died, it was this group of the nobles who were called upon to manage the empire and serve under his successors. Some of their names occur in chronicles of the time. After the elimination of the Niazis in 1547-49, Islam Shah appointed to Punjab one of his relatives, Ahmad Khan Sur, who was the son-in law of Nizam and Adil Shah. So Ahmad Shah Sur was at this time the muqta of Punjab after the elimination of Niazis in 1549.

Malwa was still controlled by Shuja’at Khan, who was one of those officers of Sher Shah who survived Islam Shah’s reign. He is often referred to as ‘Sur’ in some later histories like Niamatullah’s Tarikh-i Khan Jahani. But Abbas Khan never identifies him with Surs. On the other hand he gives the hint that he was related to the Niazi clan. He belonged to Sher Shah’s khasa khail. And when an attempt had been made to assassinate him by Islam Shah, he had fled to Malwa. Towards the end of Islam Shah’s reign, he was again under cloud and if Islam Shah would have survived, Shuja’at Khan would have been eliminated.

Mewat (that is the whole wilayat extending from Mewat located south-east of Delhi, upto Jodhpur, including Ajmer and Ranthambhor, that is to say the whole of Rajputana) during the reign of Sher Shah was controlled by the khasa khails. After him the region was controlled by Haji Khan Sultani, a non-Afghan noble who belonged to Sher Shah’s khasa khail. He was again one of those who had survived Islam Shah.

The wilayat of Bengal, having 19 sarkars was controlled by Sur officers raised to high positions by Islam Shah, such as Muhammad Khan Sur or Muhammad Khan Gauria (the titled being so as he had lived a long time at Gaur). He was a powerful Sur officer who had risen after the elimination of other Sher Shah’s officers here.

The charge of sarkar Bayana was controlled by Ghazi Khan Sur. It was a geographically significant territory as being located west of Agra, anyone stationed there could put pressure on Agra. Ghazi Khan had become influential by this time due to his relationship with the Sur clan. He was the father of Ibrahim Khan Sur, who was married to Nizam’s daughter. He had made efforts to ascend the throne by the critical support of his father.

Then the Kararani Afghan tribe had risen to prominence under Sher Shah. They had come on the top in clash with Sher Shahi nobles under Islam Shah. Taj Khan Kararani, the senior-most Kararani noble had played an important role in the elimination of the khasa khails. Taj Khan was the muqta of Sambhal under Islam Shah.

He was holding a number of parganas in Awadh as iqta. The rich parganas like Lucknow, Allahabad and Kakori were held by him at the time of Islam Shah’s death.

Another Kararani noble, Ahmad Khan Kararani was holding the charge of the wilayat of Jaunpur. Still further west, one of the brothers of Taj Khan, Sulaiman Khan Kararani had the charge of Bihar at this time. The Kararanis, thus together were controlling a very large part of the Sur Empire. All of them were strong adherents of Islam Shah.

Then of course, there were a few other important sarkars, for example, the sarkar of Kannauj, controlled by Shah Muhammad Farmuli who was originally a noble of the Lodi Empire. Shah Muhammad Farmuli did not enjoy any high position under Sher Shah, who was averse to giving high position to the remnants of the Lodi nobility exception being one or two. But when struggle arose between Sher Shahi and Islam Shahi nobles, Islam Shah used some remnants of the Lodi nobility in putting down his enemies. Thus the Farmulis under Shah Muhammad regained the high position they had held under the Lodis.

Another group of the same category was the Nauhanis who had been neglected by Sher Shah. Under Islam Shah they had improved their position. Thus the sarkar Bahraich situated to the north of Awadh was controlled by Rukn Khan Nauhani.

So it is obvious that the people who were in control were those promoted by Islam Shah. Shuja’at Khan and Haji Khan Sultani were the only two exceptions, who had also held similar positions under Sher Shah. They were loyal to Sher Shah’s family.

2. The Successors

After the death of Islam Shah, Firoz who was 2-3 years old was put on the throne.

Within a fortnight or so he was killed by his maternal uncle, Mubariz, the son of Nizam, who declared himself the king with the title of Adil Shah. He came to be known as ‘Adili’. With his accession a struggle arose. The nobility refused to co- operate with him.

One can put forward only two explanations for the manner in which the nobles refused to co-operate with Adili and came out in the open against him. One explanation is the revulsion which was created against Adili over the assassination of Firoz, not only because it was a barbaric act but also because many of the nobles who were intensely loyal to Sher Shah’s dynasty, including those raised to high positions by Islam Shah, felt revolted that the last surviving member of Farid’s dynasty had been put to death and the kingship had passed to the hands of Sher Shah’s step brother (Nizam) who was also a rival of Sher Shah.

Secondly, it was also a result of the deliberate policy pursued by Adil Shah which was aimed at replacing Islam Shah’s nobles by two set of nobles of whose loyalty he was more certain. One set of noble brought to prominence were those Sher Shahi nobles who were in rebellion against Sher Shah for most part of the reign. They were people like Isa Khan Niazi, one of the surviving members of the Niazi clan. Then there were persons like Shamsher Khan, the younger brother of Khawas Khan, son of Sukha.

Then there was Sarmast Khan, a member of a minor Afghan tribe of Sarvini, which was put on a low ladder by the Afghan nobility. He had risen to power and status during the early part of Islam Shah’s reign, but then had fallen from his grace and an attempt had been made to eliminate him. He was now taken in by Adil Shah.

Others were his personal adherents, some of whom were non-Afghans. For example Hemu, who from the time of Islam Shah was a noble of some status? He was a Brahmin of the Gaur caste who hailed from Rewari in the Mewat region. He had been a shahna-i bazar and had risen as a noble under Islam Shah on account of his competence. In 1551 he was important enough to be sent receive Mirza Kamran when the later came to visit Islam Shah for seeking help against Humayun. His position under Adil Shah was unprecedented: he was enjoying the same position as that of the wakil us saltanat under the Mughals – he exercised powers over the nobles in the name of Adil Shah. Although the office of the wakil and wazir were with Shamsher Khan, the real authority in civil and military affairs was in the hands of Hemu. He naturally inducted several persons of his clan to the Sur nobility. Example can be given of Mujahid Khan, originally a menial servant belonging to a non-Muslim caste, but converted and raised to the position of a trusted noble of Adil Shah who had affection for him. Then there was Daulat Khan, a neo- Muslim. There were a number of those nobles who had been neglected by Surs earlier, but had arisen now: e.g., Bahadur Khan Sherwani.

3. The New vs. Old Group: Revolts

The rise of such nobles was naturally resisted by the older group of Sur nobility who started opposing the policies of Adil Shah. Stances of resistance by Islam Shahi nobles against the new sultan’s attempt to dislodge them from their iqtas became noticeable in the very first few months of Adil Shah’s reign.