Political Science – 2nd Year

Paper – II (PYQs Soln.)

Comparative Government

Unit I

Modern Comparative Politics is a major field of political science that examines and compares political systems, structures, and behaviors across different countries to understand patterns, causes, and consequences of political phenomena. Unlike earlier comparative studies that largely focused on descriptive accounts of political institutions, modern comparative politics is theoretically driven and often employs empirical methods to analyze data across countries. By exploring a wide range of political environments, it seeks to build generalizable theories about how political systems work, how they influence societal outcomes, and how they differ across contexts. Modern comparative politics is shaped by several defining features, including behavioralism, structuralism, institutionalism, rational choice theory, political culture, and the study of globalization and transnational factors.

Behavioralism

One of the major shifts in modern comparative politics is the emphasis on political behavior rather than just institutions. Behavioralism, which gained prominence in the mid-20th century, argues that understanding politics requires examining the individual and collective actions of people within political systems. This approach focuses on voter behavior, political participation, interest group activities, and elite decision-making, viewing politics as the result of human behavior rather than just structural arrangements.

The behavioralist approach uses quantitative methods and data analysis to identify patterns in political behavior across different countries. For instance, behavioralism might analyze factors such as voting patterns, political efficacy, ideology, and political attitudes to explain why certain political outcomes occur. Behavioralism has helped shift the focus of comparative politics from merely comparing formal institutions to understanding how these institutions function in practice, based on the behavior and attitudes of those within the political system.

Structuralism

Structuralism is another key feature of modern comparative politics that emphasizes the economic and social structures influencing political outcomes. Structuralist theories argue that political systems cannot be fully understood without considering the underlying economic relationships and class structures within a society. For example, Marxist approaches to comparative politics fall within structuralism, focusing on how class relations and the distribution of economic power affect political systems and policies.

Structuralism often looks at factors such as class divisions, resource distribution, and economic dependencies to explain why political systems develop in certain ways. Structuralist approaches have been used to explain phenomena like authoritarianism, democracy, and revolution, suggesting that political outcomes are closely linked to a society’s economic base and the relationships between social groups. For example, dependency theory in Latin America posits that the region’s political and economic development is heavily influenced by global economic structures that perpetuate inequalities between wealthy and poor countries.

Institutionalism

Institutionalism has become increasingly important in modern comparative politics, as scholars examine how formal and informal institutions shape political behavior and outcomes. Institutions are rules, norms, and structures that guide political life, including constitutions, electoral systems, bureaucracies, and legal systems. Institutionalism in comparative politics is concerned with how these institutions influence political stability, decision-making, and policy implementation.

One prominent strand, new institutionalism, emphasizes the idea that institutions are not just the background against which politics happens, but they actively shape political behavior by establishing incentives and constraints. For example, electoral systems (e.g., proportional representation vs. first-past-the-post) can determine the number of political parties in a system and the likelihood of coalition governments. Institutionalism also considers informal institutions, such as clientelism or patronage networks, which may operate outside formal rules but still significantly influence political outcomes.

By comparing institutions across countries, institutionalist approaches help explain why similar countries might develop very different political systems. For example, comparative studies might explore why parliamentary systems tend to have higher levels of party discipline compared to presidential systems or how federal structures can affect the distribution of power within a country.

Rational Choice Theory

Rational choice theory is a theoretical framework in comparative politics that examines how individuals make political decisions based on rational calculations to maximize their self-interest. This approach assumes that political actors—whether voters, politicians, or organizations—make choices after considering the costs and benefits of different actions.

In comparative politics, rational choice theory is often used to explain electoral behavior, coalition formation, and policy choices. For instance, rational choice theorists analyze how political parties in democratic systems position themselves to appeal to the median voter, as well as how interest groups influence policy by maximizing their lobbying efforts. Rational choice theory has been applied to voting behavior across countries, explaining why voters may choose one party over another based on policy preferences, economic expectations, or short-term gains.

While rational choice theory has faced criticism for sometimes oversimplifying human behavior and ignoring social context, it has provided important insights into strategic interactions in politics. Comparative studies have used rational choice theory to explore phenomena such as coalition politics in multi-party systems and the behavior of autocratic leaders who seek to maintain power through strategic repression and resource distribution.

Political Culture

Political culture is a critical concept in modern comparative politics, focusing on the values, beliefs, and attitudes that shape the political behavior of individuals and groups within a society. Political culture emphasizes how historical, cultural, and social factors influence political stability, legitimacy, and participation.

The concept of political culture can help explain why certain countries develop stable democracies while others experience frequent regime changes or authoritarianism. For example, studies in comparative politics have examined civic culture in Western democracies, looking at how public attitudes towards democracy, trust in institutions, and political engagement contribute to democratic stability. Political culture studies also explore phenomena such as nationalism, ethnic identity, and religious influences on politics, recognizing that cultural factors can play a critical role in shaping political systems.

Example: The political culture approach has been used to analyze the persistence of democratic values in Western countries, as well as the influence of Confucian values on East Asian political systems, which prioritize social harmony and authority over individual freedom. By comparing cultural values and norms across countries, political culture studies can offer explanations for the diversity in political practices and institutions around the world.

Globalization and Transnational Influences

Globalization and transnational influences are increasingly central to comparative politics, recognizing that domestic politics are often shaped by global forces. Economic integration, international organizations, migration, and global communication networks have created a more interconnected world where national boundaries are less significant. This has led to the study of how global trends and transnational actors affect domestic political systems.

For instance, comparative politics examines how international organizations (such as the United Nations, the European Union, and the World Bank) influence national policies by setting norms and providing incentives for specific policies. Additionally, non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and transnational corporations (TNCs) exert significant influence on national politics, pushing for changes in areas such as human rights, environmental policy, and labor standards.

Globalization has also brought new challenges, such as global inequality, transnational terrorism, and climate change, which require cooperative governance across borders. Comparative politics explores how states respond to these challenges, with some embracing international cooperation while others adopt nationalist or isolationist policies. This approach highlights the growing complexity of governance in a globalized world and the need for comparative analysis to understand the interplay between domestic and international forces.

Comparative Analysis of Democratization and Regime Change

One of the core themes in modern comparative politics is the study of democratization and regime change. Scholars analyze factors that lead countries to transition from authoritarian regimes to democracies or vice versa, exploring political, social, and economic conditions that facilitate or hinder democratic governance. This includes examining democratic consolidation, the process through which new democracies stabilize, as well as understanding democratic backsliding, where democracies revert to authoritarian practices.

Comparative studies on democratization often investigate the role of civil society, economic development, political institutions, and international influences in fostering or undermining democracy. For example, modernization theory argues that as countries become more economically developed, they are more likely to adopt democratic systems due to the growth of a middle class that demands political representation. Others explore how external factors, like foreign aid or international pressure, impact democratization, particularly in countries transitioning from authoritarianism.

Methodological Advancements

Modern comparative politics has made significant strides in methodology, utilizing both quantitative and qualitative methods to analyze political systems. Comparative politics often relies on cross-national statistical analyses, using large datasets to identify patterns and causal relationships between variables such as economic development, education levels, and political stability. Advanced statistical techniques, like regression analysis and experimental designs, allow researchers to make inferences about causal relationships in complex political phenomena.

At the same time, qualitative methods—such as case studies, interviews, and process tracing—remain valuable in comparative politics. These methods are particularly useful for studying unique political systems, historical developments, and detailed mechanisms of change. Qualitative comparative analysis (QCA) combines elements of both approaches to analyze patterns across small-to-medium sample sizes.

Conclusion

Modern comparative politics encompasses a diverse array of approaches and focuses on understanding political systems through behavioral, structural, institutional, rational, cultural, and global lenses. By employing a range of methodologies and theories, modern comparative politics seeks to provide insight into the complexities of political life in different countries, offering explanations for both universal patterns and unique differences. As global challenges and international influences continue to grow, comparative politics remains essential for understanding how political systems adapt, transform, and influence the lives of people across the world.

The political systems approach in comparative politics, derived from the work of political scientist David Easton, provides a framework for analyzing how different political entities function within broader social contexts. This approach, which emerged in the mid-20th century, has become one of the foundational models in the field of comparative politics, offering insights into how political systems interact with their environments and manage demands, stresses, and change.

Theoretical Foundations and Key Concepts

The political systems approach is grounded in systems theory, originally developed in the natural sciences and later adapted to the social sciences. David Easton defined a political system as “a set of interactions abstracted from the totality of social behavior, through which values are authoritatively allocated.” This definition highlights the interactional and functional aspects of political systems and the role of authority and legitimacy in governance.

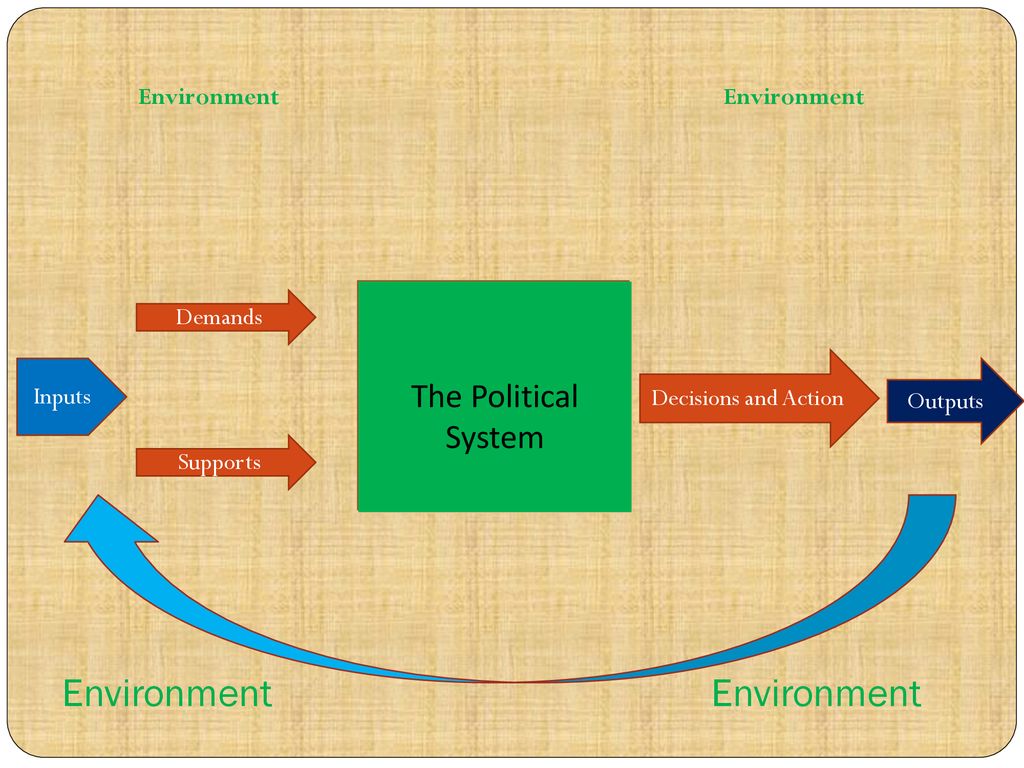

Easton’s model of a political system includes three primary components:

Inputs: These are the demands and supports that arise from society and influence the political system. Demands represent the needs or requests from individuals and groups (e.g., calls for economic reform, education, healthcare improvements), while support refers to the legitimacy and backing provided by the populace.

Process (or Throughput): This is where demands are converted into authoritative decisions or policies. The process involves complex interactions within the system, including decision-making, policy formulation, and implementation. It reflects how the political system processes societal demands and transforms them into binding outputs.

Outputs: These are the decisions, policies, and actions taken by the political system in response to inputs. Outputs have an impact on society, influencing social, economic, and political landscapes and, in turn, affecting future demands and support levels.

Feedback Loop: One of the key contributions of Easton’s approach is the emphasis on feedback, where the results of political outputs feed back into the system, influencing future demands, supports, and the system’s overall stability. Feedback allows the system to adjust to societal changes and either enhance or diminish its legitimacy.

Importance and Contributions

The political systems approach has contributed significantly to comparative politics by providing a structured method to examine how different political entities function within various socio-economic and cultural environments. Some of the main contributions of this approach include:

Holistic Perspective: The systems approach emphasizes the interconnectedness of a political system with its social, economic, and cultural environment. This holistic view enables researchers to understand how external pressures influence political stability and decision-making processes, offering a more integrated understanding of governance.

Stability and Change Analysis: The model’s feedback mechanism allows for the analysis of stability and change within political systems. By understanding how feedback impacts inputs, researchers can assess the adaptability and resilience of political systems over time. For example, Easton’s model helps explain why some systems, like democracies, tend to have more adaptive feedback mechanisms, while authoritarian regimes may struggle to address societal demands, risking instability.

Cross-Cultural Applicability: The political systems approach is widely applicable across different political contexts, enabling comparative studies between various forms of government, from democracies to authoritarian regimes. This adaptability makes it a powerful tool for comparing systems across nations, highlighting common patterns and differences.

Focus on Legitimacy and Authority: Easton placed a strong emphasis on the importance of legitimacy in the stability of political systems. When a system loses legitimacy, it risks a loss of support, increased demands for change, and potentially, systemic breakdown. This focus is critical for analyzing contemporary issues like political disenchantment, populism, and the decline of democratic institutions in various parts of the world.

Practical Applications in Comparative Politics

The political systems approach has been used extensively to study a wide range of political phenomena, such as political stability, policy-making processes, and regime change. Some of the prominent applications include:

Analyzing Democratic Resilience: In democracies, the systems approach helps examine how institutions respond to citizens’ demands and how feedback mechanisms (e.g., elections, referendums) reinforce or weaken democratic legitimacy. Comparative studies have applied this model to understand why some democracies are more resilient to crises than others, examining the feedback process in places like Western Europe versus emerging democracies in Eastern Europe.

Authoritarian Regime Stability: The approach has also been used to evaluate authoritarian systems, where feedback mechanisms are often suppressed. The absence of open feedback channels in authoritarian regimes can lead to discontent and unrest, as societal demands go unaddressed. This has been evident in various historical cases, such as the fall of the Soviet Union or recent political instability in authoritarian states where political suppression ultimately led to crises.

Policy Analysis in Developing Nations: The systems approach has been instrumental in studying policy effectiveness in developing countries, where governments face significant demands from their populations for services like healthcare, education, and infrastructure. By understanding the demand-support dynamic and feedback mechanisms, researchers can assess how these governments adapt their policies to maintain legitimacy and respond to evolving social needs.

Limitations and Criticisms

While the political systems approach has provided valuable insights, it is not without limitations. Some of the main critiques include:

Abstract and Mechanical: Critics argue that Easton’s model is overly abstract and treats political systems as mechanistic entities. This simplification overlooks the complexities of human behavior, individual agency, and ideological conflicts that shape political outcomes. By emphasizing system processes, the approach may fail to capture the nuances of political struggles and individual motivations.

Limited Agency and Power Dynamics: The political systems approach has been criticized for its lack of focus on power relations and agency within political systems. Unlike models that emphasize conflict, negotiation, and power struggles, Easton’s framework primarily views politics as a process of managing demands and support, downplaying the significance of political actors and groups that influence decision-making through power and coercion.

Inadequate Explanation of Change: Although Easton incorporated feedback mechanisms, critics argue that the model is limited in explaining fundamental political transformations and revolutionary changes. The systems approach is more effective in explaining incremental change within stable systems, but it struggles to address why some systems experience sudden and profound upheavals, as seen in revolutions or regime collapses.

Ethnocentric Bias: Some scholars argue that the model has an ethnocentric bias due to its origins in Western political thought. It may not fully account for the unique cultural and historical factors influencing non-Western political systems, especially those that do not fit neatly into a systems-based framework. This has led to critiques that the model imposes a Western-centric view of political stability and legitimacy.

Conclusion

The political systems approach has been a significant advancement in comparative politics, providing a structured way to analyze how political systems manage societal demands, maintain stability, and adapt to change. Its contributions to understanding political stability, legitimacy, and resilience have shaped both theoretical and empirical studies, offering insights into democratic resilience, authoritarian stability, and policy-making dynamics in diverse contexts.

However, the model’s limitations—particularly its abstract nature, limited focus on power dynamics, and challenges in explaining transformative change—suggest the need for complementary approaches. Despite these critiques, the political systems approach remains an influential model in comparative politics, valuable for understanding institutional stability, legitimacy, and policy adaptation in a rapidly changing world.

Comparative politics is a significant branch of political science. It provides an insightful lens to examine and interpret the myriad political structures that govern societies across the globe.

What is Comparative Politics?

Comparative politics is a technique in political science that involves examining and contrasting different political systems to decipher the complex characteristics of political phenomena. By conducting comparative analyses of diverse political systems, structures, functions, and performances, comparative politics enhances our understanding of governance patterns and political behaviours across nations.

Key domains within comparative politics consist of:

- Diverse political systems and their structures

- The interplay of political behaviour and ideology

- The formulation and execution of public policies

- The principles and practices of governance and democracy

- The mechanisms of political development and change

History and Evolution of Comparative Politics

The origins of comparative politics can be traced back to ancient Greek philosophers such as Aristotle. They compared the constitutions of different city-states. However, it was not until the 19th century that comparative politics emerged as a distinct subfield of political science. This was due in part to the expansion of European empires and the increasing need to understand different political systems.

Nature and Scope of Comparative Politics

The nature of comparative politics is multi-faceted, with each aspect contributing towards a broader comprehension of global political systems.

- Comparative politics adopts a global perspective, enabling the comparison of political systems, institutions, or behaviours across different countries.

- The nature of comparative politics extends beyond description; it is fundamentally analytical. It offers a detailed analysis of political phenomena, fostering a thorough understanding of the subject.

- Comparative politics endeavours to decipher causal relationships. It seeks to answer not only the ‘what’ and ‘why’ but also the ‘how’ – delving deeper than merely describing political phenomena to explain the cause-effect relationship.

- The nature of comparative politics intersects with numerous other disciplines, such as sociology, economics, and anthropology. This multidisciplinary approach provides a holistic view of political phenomena.

Approaches of Comparative Politics

There are a variety of approaches to comparative politics, each with its own strengths and weaknesses. Some of the most common approaches include:

Traditional Approach

The traditional approach to comparative politics is based on the study of formal political institutions. This includes legislatures, executives, and judiciaries. This approach focuses on the structure and functions of these institutions. It also deals with the relationships between them.

Behavioral Approach

The behavioral approach to comparative politics emerged in the mid-20th century. It emerged as a reaction to the traditional approach. Behaviorists argue that the study of formal institutions is not enough to understand how political systems actually work. They focus on the behavior of political actors, such as voters, parties, and interest groups.

Structural Approach

The structural approach to comparative politics focuses on the broader social, economic, and international forces that shape political systems. Structuralists argue that these forces play a key role in determining:

- the distribution of power and

- the outcomes of political processes.

Cultural Approach

The cultural approach to comparative politics focuses on the role of culture in shaping political systems and processes. Culturalists argue that cultural values and norms play an important role in determining:

- how people think about politics and

- how they take part in political life.

Rational Choice Approach

The rational choice approach to comparative politics is based on the assumption that political actors are rational actors. They make decisions based on their own self-interest. Rational choice theorists use game theory and other economic models to study political behavior.

Significance of Comparative Politics

The study of comparative politics offers multiple benefits:

- Comparative politics provides a deeper understanding of global political systems, their institutions, functions, and behaviors, which enriches knowledge and fosters global perspectives.

- Comparative politics can reveal the likely outcomes of policy decisions by studying similar policies in different political contexts. This understanding can influence better policy-making and reform.

- By studying the factors that contribute to democratic development and stability in different countries, comparative politics can provide valuable insights into strengthening democratic systems.

Limitations of Comparative Politics

Despite its many advantages, comparative politics is not without limitations:

- The extreme variability in political systems worldwide can make it challenging to draw precise comparisons and could potentially lead to inaccurate conclusions.

- Comparative politics may often overlook the influence of unique cultural contexts on political systems, thus potentially missing crucial nuances in the analysis.

- Drawing causal inferences in comparative politics can be challenging due to the complex and interdependent nature of political phenomena.

The modern approach to comparative politics emerged as a response to the limitations of the traditional approaches that had previously dominated the field. Comparative politics as a discipline sought to understand political systems across countries, but early methods were often descriptive, Eurocentric, and focused on normative questions rather than empirical analysis. The development of a modern approach reflected a shift toward scientific rigor, empirical research, and systematic comparison across different political systems, grounded in both social science methodologies and interdisciplinary insights.

The Need for a Modern Approach in Comparative Politics

Shortcomings of the Traditional Approach

The traditional approach to comparative politics, also known as the legal-institutional approach, was primarily concerned with the formal institutions of government—such as constitutions, legislatures, and courts. Rooted in legalistic and historical methods, this approach was often descriptive rather than analytical, focusing on the formal structures of government in individual countries without systematically comparing their processes or outcomes. Several factors necessitated the shift toward a modern approach:

Descriptive and Normative Focus: Traditional approaches in comparative politics were largely descriptive, detailing how government structures were organized in various states but lacking a broader analysis of political dynamics and processes. It also had a normative bias, often prescribing what “should be” rather than investigating what “is.”

Eurocentrism and Limited Scope: Early comparative studies were heavily Eurocentric, focusing primarily on Western political systems. This limited scope failed to address the diversity and complexity of political systems in non-Western countries, particularly in newly independent states in Africa, Asia, and Latin America.

Static Analysis: Traditional approaches often ignored the dynamic aspects of political life, such as social movements, class conflicts, and ideological shifts. These approaches viewed political systems as static and fixed entities, without acknowledging the continuous processes of change, adaptation, and influence exerted by social, economic, and cultural factors.

Lack of Empirical Rigor: The traditional approach relied on historical and legalistic methods rather than empirical data, limiting its ability to provide accurate, evidence-based insights into political phenomena. This lack of empirical rigor made it challenging to generalize findings and test hypotheses, an essential part of scientific inquiry.

Global Political Changes and the Rise of Behavioralism

The need for a modern approach was also driven by post-World War II global transformations and the rise of new social science methodologies, such as behavioralism. During this period, the world saw a wave of decolonization, leading to the emergence of many new states with distinct political systems and challenges. Scholars recognized that the legal-institutional focus of traditional approaches was insufficient to understand the complexities of governance and political development in these newly formed states. The behavioral revolution in political science further emphasized the importance of empirical research, quantitative methods, and focus on political behavior over mere institutional descriptions.

Behavioralism encouraged the study of politics as an empirical science, with an emphasis on hypotheses, data collection, and the study of political behavior, including voting patterns, political socialization, and elite dynamics. This paved the way for the development of a more comprehensive and systematic approach in comparative politics that could be applied universally.

Characteristics of the Modern Approach to Comparative Politics

The modern approach to comparative politics incorporates a range of theoretical frameworks and methodologies, drawing from fields such as sociology, psychology, and economics. The main features of the modern approach include:

Empirical and Scientific Methods: The modern approach emphasizes the scientific method, using empirical data, hypothesis testing, and statistical techniques to understand political phenomena. Quantitative methods, such as survey research and regression analysis, became crucial for collecting and analyzing data on political behavior, institutions, and policies.

Focus on Political Processes and Behavior: Unlike the traditional focus on formal structures, the modern approach examines political processes and behavior within and around these structures. This includes studying political participation, party competition, leadership styles, political socialization, and the impact of public opinion on policy-making.

Comparative and Cross-National Analysis: The modern approach prioritizes systematic comparison across countries, rather than studying political systems in isolation. Scholars look for patterns, similarities, and differences across different political systems, which allows for more generalizable conclusions and insights.

Interdisciplinary Perspective: Modern comparative politics integrates insights from multiple disciplines, including economics, sociology, and anthropology, to develop a more nuanced understanding of political dynamics. For example, the modernization theory uses insights from economics to explain how economic development influences political change.

Focus on Systemic Theories and Models: Building on systems theory, scholars like David Easton developed models that view political systems as entities interacting with their environment. This led to theories such as the political systems approach, structural-functionalism, and dependency theory, which allowed for a more comprehensive understanding of how different political systems function and adapt to change.

Is the Modern Approach an Improvement?

The modern approach marks a significant improvement over the traditional approach in several ways, enhancing both the depth and breadth of comparative political analysis. Some key improvements include:

1. Greater Explanatory Power

The modern approach provides a better understanding of political behavior, social influences, and economic factors affecting governance. While the traditional approach often focused on the “ideal” structure of government, the modern approach investigates how institutions work in practice and how they are affected by broader social forces. For example, political culture theory, developed by Gabriel Almond and Sidney Verba, shows how cultural attitudes toward authority and civic participation influence democratic stability, a factor overlooked by traditional models.

2. Ability to Address Complex Political Phenomena

The modern approach enables scholars to address complex political phenomena such as political development, regime change, and political instability. Through theories like dependency theory and world-systems theory, modern comparative politics explores how global economic structures and colonial histories shape political outcomes in developing nations.

3. Enhanced Scientific Rigor

By emphasizing empirical research, the modern approach provides a scientifically rigorous foundation for comparative politics. Hypotheses can be tested, variables can be measured, and patterns can be identified with a degree of precision unavailable to traditional approaches. This empirical basis allows for more reliable and valid conclusions.

4. Comparative Focus and Global Applicability

Modern approaches are not limited to Western systems and can be applied across diverse contexts, making them better suited to understanding political phenomena in the Global South. The post-colonial states of Africa and Asia, for example, pose unique challenges to governance, often marked by ethnic diversity, economic dependency, and weak institutional structures. Modern approaches, such as state theory and post-colonial theory, address these unique political realities, while traditional approaches failed to account for them adequately.

5. Theoretical Diversity and Innovation

The modern approach has led to a rich array of theories and models that offer multiple perspectives on political phenomena. For instance, rational choice theory focuses on how individuals make decisions based on self-interest, while institutionalism examines how institutions shape political outcomes. This diversity of approaches allows for a deeper and more flexible understanding of politics.

Criticisms and Limitations of the Modern Approach

While the modern approach has clear advantages, it is not without its criticisms:

Reductionism and Over-Quantification: Some critics argue that the modern approach is overly quantitative, which can lead to reductionism, where complex political phenomena are oversimplified into numerical data, losing valuable contextual nuances.

Lack of Emphasis on Normative Analysis: The focus on empirical analysis has led some to criticize the modern approach for neglecting normative questions about what “ought to be” in political systems. Some argue that understanding ethical and moral dimensions is essential to the study of governance and justice.

Ethnocentrism in Theoretical Models: Some theories within the modern approach, such as modernization theory, have been critiqued for their Western-centric assumptions about economic and political development, which do not always align with the experiences of non-Western societies.

Conclusion

The modern approach to comparative politics represents a substantial improvement over the traditional approach, addressing its limitations by incorporating scientific rigor, empirical analysis, and cross-national comparisons. It provides a more comprehensive and flexible framework for understanding diverse political systems, political behavior, and the impact of social, economic, and cultural factors on governance. By moving beyond the limitations of descriptive and normative analysis, the modern approach has allowed comparative politics to evolve into a truly scientific discipline, capable of analyzing complex and global political phenomena.

However, as with any approach, it is essential to recognize the limitations of modern methods and to continue refining them, especially to accommodate diverse cultural and political contexts. Despite its criticisms, the modern approach remains a pivotal step in the evolution of comparative politics, transforming the field into a rigorous, scientifically grounded area of study that is well-equipped to address the complexities of contemporary political life.

Comparative politics is the subfield of political science that involves the systematic analysis, comparison, and study of various political systems, institutions, processes, behaviors, and outcomes across different countries or regions. This discipline seeks to identify patterns, similarities, and differences among political entities in order to develop insights, theories, and generalizations about political phenomena and their underlying causes. By examining and comparing different cases, comparative politics aims to provide a deeper understanding of how political systems function and how they respond to challenges within diverse cultural, historical, and social contexts.

The primary goal of comparative politics is to identify patterns, trends, and factors that influence political outcomes in different countries. Researchers in this field often compare different countries or regions to draw insights and develop theories about political phenomena. By comparing different cases, scholars can identify general principles and causal relationships that may shed light on the functioning of political systems and the factors that shape them.

According to John Blondel, comparative politics is “the study of patterns of national governments in the contemporary world”.

M.G. Smith described that “Comparative Politics is the study of the forms of political organisations, their properties, correlations, variations and modes of change”.

E.A Freeman stated that “Comparative Politics is comparative analysis of the various forms of govt. and diverse political institutions”.

Comparative politics can encompass a wide range of topics, including:

- Political Institutions: Comparative politics studies the structures of government, including systems such as democracies, autocracies, and hybrid regimes. It examines the roles and powers of various branches of government, electoral systems, and legal frameworks.

- Political Culture and Behavior: This area focuses on citizen attitudes, political participation, voting behavior, and political ideologies. It explores how cultural and social factors influence political preferences and actions.

- Public Policy: Comparative politics analyzes how different countries develop and implement policies to address challenges in areas such as economics, healthcare, education, and social welfare.

- State-Society Relations: This topic explores the interaction between governments and civil society, including social movements, interest groups, and non-governmental organizations.

- Conflict and Cooperation: Comparative politics examines the causes of domestic and international conflicts, as well as mechanisms for conflict resolution and cooperation between nations.

- Development and Governance: Scholars study how different political systems impact economic development, governance effectiveness, and the distribution of resources.

Evolution

The evolution of comparative politics as a subfield within political science has undergone several key stages over time. While the following overview is not exhaustive, it highlights some of the significant developments and shifts that have shaped the field’s progression:

- Early Foundations and Area Studies (19th Century – Early 20th Century): Comparative politics has roots dating back to the 19th century, where scholars like Alexis de Tocqueville and Max Weber made comparative observations about political systems. This early stage often focused on studying individual countries or regions in isolation, emphasizing cultural and historical factors.

- Modernization Theory and Behavioralism (Mid-20th Century): In the mid-20th century, the field began to evolve with the emergence of modernization theory and behavioralism. Scholars sought to identify universal patterns of political development and behavior across different countries, focusing on factors such as economic development, industrialization, and citizen attitudes. Comparative studies were conducted with an aim to discover generalizable principles.

- Institutionalism and Structured Comparisons (1960s – 1970s): During this period, there was a growing emphasis on examining political institutions and their impact on political behavior and outcomes. Comparative politics increasingly used structured and systematic methods to compare political systems, focusing on variables such as electoral systems, party systems, and executive-legislative relations.

- Critiques and Cultural Turn (1980s – 1990s): The 1980s and 1990s saw a shift toward critiques of the assumptions underlying comparative politics. Scholars questioned the applicability of Western theories to non-Western contexts and highlighted the importance of cultural, historical, and contextual factors in shaping political outcomes. This period saw the rise of postcolonial and feminist perspectives within the field.

- New Institutionalism and Rational Choice (Late 20th Century): The late 20th century witnessed the rise of new institutionalism and rational choice approaches within comparative politics. These perspectives focused on formal political institutions and their role in shaping political behavior and outcomes. Rational choice theory emphasized the rational calculations of individuals in making political decisions.

- Globalization and Complex Interdependence (Late 20th Century – 21st Century): As globalization intensified, comparative politics expanded its focus to include the study of international factors that influence domestic politics. This period saw increased attention to topics such as transnational issues, global governance, and the impact of international organizations on state behavior.

- Methodological Innovations and Mixed Methods (21st Century): Contemporary comparative politics continues to evolve with the integration of quantitative and qualitative research methods. Scholars often employ mixed-method approaches to gain a more comprehensive understanding of complex political phenomena. Additionally, the field increasingly engages with interdisciplinary approaches, incorporating insights from sociology, anthropology, economics, and other disciplines.

Throughout its evolution, comparative politics has become more inclusive, recognizing the diversity of political systems and the importance of context in shaping political outcomes. The field remains dynamic, adapting to changes in the global political landscape and incorporating new theoretical perspectives and methodological tools.

Comparative governments vs Comparative politics

Comparative governments and comparative politics are closely related subfields within political science that share similarities but also have distinct focuses and objectives. Here’s a comparison between the two:

1. Scope and Focus:

- Comparative Governments: This subfield primarily focuses on the examination of the structures, functions, and dynamics of various governmental systems. It delves into the specific institutions, branches of government, and decision-making processes within different political systems.

- Comparative Politics: Comparative politics, on the other hand, takes a broader approach by analyzing not only governmental structures but also the entire political landscape, including institutions, political behavior, public policies, political culture, and more.

2. Level of Analysis:

- Comparative Governments: This subfield often employs a micro-level analysis, zooming in on the details of specific government institutions, such as executive offices, legislatures, and judiciaries.

- Comparative Politics: Comparative politics operates at a more macro-level, considering a range of factors that influence the functioning of political systems. It includes the interactions between various political institutions and actors.

3. Emphasis:

- Comparative Governments: The main emphasis here is on the structural aspects of government, such as the design of constitutions, forms of executive leadership, types of legislatures, and judicial systems.

- Comparative Politics: This subfield emphasizes the broader study of political systems, their interactions, and their outcomes. It looks at how political institutions, behavior, and culture interact and influence one another.

4. Questions Addressed:

- Comparative Governments: Researchers in this subfield may address questions related to how different forms of government (e.g., presidential vs. parliamentary) affect policy-making, governance, and decision-making.

- Comparative Politics: Comparative politics researchers address a wide range of questions, including the study of political ideologies, public opinion, social movements, political parties, electoral systems, and the impact of globalization on political systems.

5. Methodology:

- Comparative Governments: Research in this subfield often involves in-depth analysis of specific government structures and institutions using case studies, interviews, and document analysis.

- Comparative Politics: Research methods in comparative politics vary widely and can include both qualitative and quantitative approaches. Researchers may use cross-national statistical analysis, surveys, ethnography, and historical research to explore political phenomena.

6. Interdisciplinary Connections:

- Comparative Governments: While still rooted in political science, comparative governments may have stronger connections to legal studies and constitutional law due to its focus on government structures.

- Comparative Politics: Comparative politics often integrates insights from various disciplines, including sociology, anthropology, economics, and international relations, to provide a more holistic understanding of political systems.

In summary, while both comparative governments and comparative politics involve the study of political systems, the former focuses more narrowly on governmental structures and processes, whereas the latter takes a broader approach encompassing a wider range of political phenomena and interactions.

Nature of Comparative politics

The nature of comparative politics is characterized by its interdisciplinary approach, its focus on cross-national analysis, and its exploration of the diverse elements that shape political systems and behaviors. Here are some key aspects that highlight the nature of comparative politics:

- Interdisciplinary Approach: Comparative politics draws on insights and methodologies from various disciplines, including political science, sociology, anthropology, economics, history, and more. This interdisciplinary approach helps provide a comprehensive understanding of political systems by considering cultural, historical, economic, and social factors.

- Cross-National Analysis: At its core, comparative politics involves the systematic comparison of political systems, institutions, behaviors, and outcomes across different countries or regions. This cross-national analysis allows researchers to identify patterns, similarities, and differences that shed light on the functioning of political systems and the factors that influence them.

- Contextual Sensitivity: Comparative politics recognizes the importance of context in shaping political outcomes. It acknowledges that political systems are embedded within specific cultural, historical, and social contexts, and therefore, a one-size-fits-all approach may not be appropriate. This sensitivity to context contributes to a more nuanced understanding of political phenomena.

- Theory Development: Comparative politics aims to develop theories and generalizations about political behavior and outcomes. By systematically comparing different cases, researchers can identify underlying causal mechanisms and principles that explain why certain political phenomena occur. These theories contribute to the broader body of knowledge in political science.

- Methodological Pluralism: Comparative politics employs a wide range of research methods to explore political systems. Researchers use both quantitative methods (statistical analysis, surveys) and qualitative methods (case studies, ethnography) to gather data and generate insights. The choice of method often depends on the research question and the nature of the phenomena being studied.

- Focus on Political Institutions and Behavior: Comparative politics examines not only the formal structures of political institutions (such as legislatures, executives, and judiciaries) but also the behavior of political actors, including citizens, political parties, interest groups, and elites. This dual focus provides a comprehensive view of how political systems function.

- Globalization and Interdependence: The nature of comparative politics has evolved to reflect the increasing interconnectedness of the world. Scholars now examine how international factors, such as globalization, trade, migration, and international organizations, impact domestic political systems and policies.

- Diversity of Political Systems: Comparative politics recognizes the diversity of political systems around the world. It encompasses the study of democracies, autocracies, hybrid regimes, federal systems, and various other governance structures. This diversity allows for a more inclusive understanding of political realities.

- Practical Relevance: Comparative politics has practical implications for policymakers, international relations, and global governance. Insights gained from cross-national analysis can inform policy decisions, aid in conflict resolution, and contribute to a deeper understanding of global political dynamics.

In essence, the nature of comparative politics involves exploring the complexities of political systems through a multi-faceted lens, considering context, theory, methodology, and interdisciplinary perspectives to achieve a more comprehensive understanding of political phenomena.

Scope of comparative politics

The scope of comparative politics is broad and encompasses a wide range of topics, issues, and areas of inquiry. It involves the systematic study and analysis of political systems, institutions, behaviors, and outcomes across different countries or regions. Here are some key areas that fall within the scope of comparative politics:

- Political Institutions: Comparative politics examines various political institutions such as executive branches, legislatures, judiciaries, and local governments. It explores how these institutions are structured, how they interact, and how they shape political processes and outcomes.

- Forms of Government: The scope includes the study of different forms of government, including democracies, autocracies, monarchies, and hybrid regimes. It investigates how these forms of government function, their strengths, weaknesses, and the impact they have on citizens’ lives.

- Political Behavior: Comparative politics explores political behavior, including voting patterns, political participation, public opinion, and political ideologies. It seeks to understand why individuals and groups make certain political choices and how these choices impact the political system.

- Political Parties and Electoral Systems: This area focuses on the role of political parties, their organization, ideologies, and electoral strategies. Comparative politics also examines various electoral systems, such as proportional representation and first-past-the-post, and how they influence representation and governance.

- Public Policy: The scope includes the study of public policies across different countries, including social welfare, healthcare, education, economic policies, and environmental regulations. Researchers analyze policy formulation, implementation, and the effects of policies on societies.

- Political Culture and Identity: Comparative politics investigates the cultural and identity-based factors that influence political behavior and attitudes. It explores how cultural norms, traditions, and historical experiences shape citizens’ perceptions of politics and their engagement with the political process.

- Conflict and Cooperation: This area focuses on domestic and international conflict, negotiation, diplomacy, and conflict resolution. Comparative politics examines the causes of conflicts, how different political systems manage conflicts, and the role of international actors in mediating disputes.

- Globalization and Transnational Issues: The scope of comparative politics has expanded to include the study of how globalization impacts political systems. This includes analyzing the effects of global trade, migration, communication, and the role of international organizations on domestic politics.

- State-Society Relations: Comparative politics explores the interactions between governments and civil society, including non-governmental organizations (NGOs), social movements, interest groups, and advocacy networks. It examines how these interactions influence policy-making and political change.

- Development and Governance: The field studies the relationship between political systems and economic development, examining how different governance structures impact economic growth, poverty reduction, and inequality.

- Institutional Design and Reform: Comparative politics also delves into the design and reform of political institutions. It examines how constitutional design, electoral reforms, and institutional changes can influence political stability and democratic governance.

- Regime Transitions and Democratization: The scope includes the study of regime changes, transitions from authoritarianism to democracy, and democratic consolidation. It analyzes the factors that facilitate or hinder the establishment and maintenance of democratic political systems.

The scope of comparative politics is not limited to these areas alone; it is a dynamic and evolving field that adapts to changes in the global political landscape and incorporates emerging issues and perspectives. By systematically comparing different cases, comparative politics contributes to our understanding of political systems, their interactions, and the factors that shape their outcomes.

Conclusion

Overall, the evolution of comparative politics reflects its adaptability to changing theoretical paradigms, methodological innovations, and the complex global political landscape. As the field continues to evolve, it remains a crucial avenue for understanding political systems’ dynamics and contributing to the broader discourse on governance, democracy, and international relations.

Political investigators use different approaches tools to arrive at greater political understanding. Approaches support in defining the kinds of facts which are relevant.

The diversity of approaches is used by political scientists to attack the complexity of political systems and behaviour.

Conventionally, the study of comparative politics is termed as ‘comparative government’. It includes the study of political institutions existing in various states .The features, advantages, demerits, similarities and dissimilarities of political institutions were compared. It was an attempt to ascertain the best of political institutions. The focus (Traditional view), continued to remain popular up to the end of the 19th century. In the 20th century, the study of political government underwent revolutionary changes. The traditional focus of the study of politics got substituted by new scope, methodology, concepts, techniques which were known as contemporary view of the study of politics. Political researchers made great attempts to develop a new science of ‘comparative politics’. They espoused comprehensiveness, realism, precision and use of scientific methods as the new goals for the study of comparative politics. This new endeavour is nowadays promoted as ‘modern’ comparative politics. In the modern assessment, the scope of comparative politics is much wider. It includes the analysis and comparison of the actual behaviour of political structures, formal as well as informal. Researchers believe that these political structures, governmental or non- governmental, directly or indirectly affect the process of politics in all political systems.

Both traditional and modern comparative politics adopt different approaches to its study. Traditional scientists follow narrow and normative approach. It involves descriptive studies with a legal institutional framework and normative prescriptive focus. Whereas modern political scientists follow empirical, analytical studies with a process orientated or behavioural focus and they adopt scientific methodology. It seeks to analyse and compare empirically the actual behaviour of political structures.

TRADITIONAL APPROACHES

The traditional approach to Political Science was broadly predominant till the occurrence of the Second World War. These approaches were mainly associated with the traditional outlook of politics which underlined the study of the state and government. Consequently, traditional approaches are principally concerned with the study of the organization and activities of the state and principles and the ideas which motivate political organizations and activities. These approaches were normative and principled. The political philosophers supporting these approaches and raised questions such ‘what should be an ideal state?’ According to them, the study of Political Science should be limited to the formal structures of the government, laws, rules and regulations. Therefore, the supporters of the traditional approaches stress various norms such as what ‘ought to be’ or ‘should be’ rather than ‘what is’.

Characteristics of Traditional approaches:

- Traditional approaches are mostly normative and stresses on the values of politics.

- Prominence is on the study of different formal political structures.

- Traditional approaches made very little attempt to relate theory and research.

- These approaches consider that since facts and values are closely interlinked, studies in Political Science can never be scientific.

There are many types of traditional approaches that are as follows:

Philosophical approach

Philosophical approach is conventional approach to study politics. Customarily, the study of politics was subjugated by philosophical reflections on universal political values that were regarded as essential to the just state and the good state. The oldest approach to the study of politics is philosophical. Philosophy “is the study or science of truths or principles underlying all knowledge and being.” It entails that philosophy or philosophical approach tries to explore the truth of political incidents or events. It discovers the objective of political writings or the purpose of political writer.

Main aim of philosophical approach is to evaluate the consequences of events in a logical and scientific manner. Van Dyke opined that “philosophy denotes thought about thought. Somewhat more broadly it denotes general conceptions of ends and means, purposes and methods.” The purpose of philosophical approach is to explain the words and terms used by the political theorists. The enquiry started by the philosophical approach removes confusion about the assumptions.

Several Greek philosophers such as Plato and Aristotle were the creators of this approach. The main subject of Plato’s writings was to define the nature of an ideal society. This approach states that values are inseparable from facts. It is mainly an ethical and normative study of politics, hence is concerned with what ‘should be’ or ‘ought to be’. This approach seeks to understand our fundamental nature and aim as human beings, recognizing principles and standards of right conduct in political life. It is normative in character and believes in developing norms or certain standards. It followed the logical method where investigator has his own values and determined philosophies.

Benefit of philosophical approach is that it enters into the depth of every aspect of political phenomena and examines them without any partiality. Its interpretation of political activities conjures interest in the minds of students of politics. Words and phrases used by philosophers highlight point on the subject. Philosophical approach enhances linguistic clarity. That is why it is said that this approach aims at thought about thought.

Philosophical approach use procedure of logical analysis. It uses reason to explore the truth. The truth which this approach establishes may be of various kinds-normative, descriptive or prescriptive. But the philosophical approach is indifferent to the nature or category of truth.

This approach also tries to establish standards of good, right and just. Many critics observed that this approach determines what is in the interest of the public and he identifies interest more with ends that with means.

In the huge arena of political science, there are a number of great or outstanding books. Philosophical approach explores the meaning and central theme of these books as well as the exact purpose of the authors. In the contemporary Greek city-states of Plato morality, moral values and idealism ruined to such an extent that he received a great shock and seriously thought to recuperate these and this urge encouraged him to write The Republic. He wanted to establish that politics and morality are not an etheric concepts. Rather, an ideal and moral body politic can be made a real one through the selfless administration by a philosopher-king. John Locke composed his Second Treatise to rationalize the interests and objectives of the new middle class and he struggle of people for liberty.

Other political philosopher such as Machiavelli and Hobbes wrote to support royal absolutism. Some critics may not agree with the views of these philosophers or the arguments of these books, but it must not be forgotten that the books were written at particular and critical moment of history.

It is well established that Philosophical approach helps people to understand the contemporary history and the nature of politics suggested by philosophers. In other words, the philosophical approach aids to comprehend the political ideologies of past centuries. In this sense, the philosophical approach is very important for researchers and people.

Application of the philosophical approach in political science focuses on the great ideas, values and doctrines of politics. The normative-philosophical approach is the ancient and the least scientific approach to the study of politics and it has been taken over although not completely displaced by contemporary approaches.

Criticism of the Philosophical Approach

Though philosophical approach is highly important for scholars and other people to the study of politics, critics have raised several problems about its worth. It is documented in literature that one of the central ideas of political philosophy is idealism and it is conspicuous in Plato’s The Republic. Critics argued that idealism itself is quite good but when its practical application arises it appears to be a myth.

Plato emphasized Idealism in his theory, but it had not practical importance and be fully realised that idealism would never be translated into reality. It is a subject of absolute imagination. Machiavelli and Hobbes wrote with the only purpose of supporting the status quo.

The philosophical intellectuals of the earlier periods were impractical philosophers. They had no intention to promulgate ideas which can change society. They were apathetic to people’s liking and disliking, their love for liberty, their sorrows and sufferings and they failed to provide prophylactic devices. As an academic discipline, philosophical approach is appropriate, but in practical guide for action, it has barely any importance.

Historical approach

This approach states that political theory can be only understood when the historical factors are taken into consideration. It highlights on the study of history of every political reality to analyse any situation. Political theorists like Machiavelli, Sabine and Dunning believed that politics and history are strongly inter-related, and therefore, the study of politics always should have a historical viewpoint. Sabine considered that Political Science should include all those subjects which have been discussed in the writings of different political thinkers since Plato. History defines about the past as well as links it with the present events. Without studying the past political events, institutions and political environment, the analysis of the present would remain largely imperfect.

Main attribute of historical approach is that history as a written or recorded subject and focuses on the past events. From history, researchers come to know how man was in the past and what he is now. History is the store-house of events. From the profiles, autobiographies, descriptions by authors and journalists investigators know what event occurred in the past.

It is to be prominent that the events must have political revealing or they must be politically significant. These events provide the best materials upon which theory and principles of political science are built. History communicates researchers how government, political parties and many other institutions worked, their successes and failures and from these, they receive lessons which guide them in determining the future course of action.

Evaluation of Historical Approach: The historical approach to the study of politics has numerous challenges from several quarters. One of the main fulcrums of the challenges is that history has two faces. One is documentation of facts which is quite naive and the other is construal of facts and phenomena. The accretion of evidences is to be judged from a proper perspective.

The implication is that adequate care should be taken while evaluating evidence and facts and such a caution is not always strictly followed and, as a result, the historical facts do not serve the purpose of those who use it. This is the main complaint against the historical approach to the study of politics.

Alan Ball has also criticized the historical approach. He debated that “past evidence does leave-alarming gaps, and political history is often simply a record of great men and great events, rather than a comprehensive account of total political activity.” Very few historians interpret historical events and evidences broadly and freely .

Institutional approach

There is a strong belief that philosophy, history and law have bestowed to the study of politics and it is in the field of institutional approaches. Institutional approaches are ancient and important approach to the study of Political Science. These approaches mainly deals with the formal aspects of government and politics. Institutional approach is concerned with the study of the formal political structures like legislature, executive, and judiciary. It focused on the rules of the political system, the powers of the various institutions, the legislative bodies, and how the constitution worked. Main drawback of this approach was its narrow focus on formal structures and arrangements. In far- reaching terms, an institution can be described as ‘any persistent system of activities in any pattern of group behaviour. More concretely, an institution has been regarded as ‘offices and agencies arranged in a hierarchy, each agency having certain functions and powers.

The study of institutions has been dominant not only to the arena of comparative politics, but to the political science field as a whole. Many writers have argued that institutions have shaped political behaviour and social change. These authors have taken an “institutionalist” approach which treat institutions as independent variables.

The institutional approach to political analysis emphasises on the formal structures and agencies of government. It originally concentrated on the development and operation of legislatures, executives and judiciaries. As the approach developed however, the list is extended to include political parties, constitutions, bureaucracies, interest groups and other institutions which are more or less enduringly engaged in politics.

Though, descriptive-institutional approach is slightly old, political experts still concentrate chiefly on scrutinising the major political institutions of the state such as the executive, legislature, the civil service, the judiciary and local government, and from these examinations, valuable insights as to their organisation can be drawn, proposals for reform conversed and general conclusions obtainable. The approach has been critiqued for the disregard of the informal aspects of politics, such as, individual norms, social beliefs, cultural values, groups’ attitudes, personality and the processes. Institutional approach is also criticized for being too narrow. It ignores the role of individuals who constitute and operate the formal as well as informal structures and substructures of a political system. Another problem is that the meaning and the range of an institutional system vary with the view of the scholars. Researchers of this approach ignored the international politics (J. C. Johari, 1982).

Legal approach

In the realm of traditional approaches, there is a legal or juridical approach. This approach considers the state as the central organization for the creation and enforcement of laws. Therefore, this approach is associated with the legal process, legal bodies or institutions, and judiciary. In this approach, the study of politics is mixed with legal processes and institutions. Theme of law and justice are treated as not mere affairs of jurisprudence rather politics scientists look at state as the maintainer of an effective and equitable system of law and order. Matters relating to the organizations, jurisdiction and independence of judicial institutions become and essential concern of political scientists. This approach treats the state primarily as an organization for creation and enforcement of law (J. C. Johari, 1982).

The supporters of this approach are Cicero, Bodin, Hobbes, John Austin, Dicey and Henry Maine. In the system of Hobbes, the head of the state is highest legal authority and his command is law that must be obeyed either to avoid punishment following its infraction or to keep the dreadful state of nature away. Other scientists described that the study of politics is bound with legal process of country and the existence of harmonious state of liberty and equality is earmarked by the rule of law (J. C. Johari, 1982). The legal approach is applied to national as well as international politics. It stands on assumptions that law prescribes action to be taken in given contingency and also forbids the same in certain other situations. It also emphasizes the fact that where the citizens are law abiding, the knowledge of the law offers an important basis for predictions relating to political behaviour of people. Though it is effective approach but not free from criticism. This approach is narrow. Law include only one aspect of people’s life. It cannot cover entire behaviour of political actions (J. C. Johari, 1982).

Criticism of traditional approaches

The traditional approaches have gloomily unsuccessful to identify the role of the individuals who are important in moulding and remoulding the shape and nature of politics. In fact, individuals are important players of both national and international politics. The focus is directed to the institutions.

It is astounding that in all the institutions, there are individuals who control the structure, functions and other aspects. Singling out institutions and neglecting individuals cannot be pronounced as proper methods to study politics. The definition politics as the study of institution is nothing but an overstatement or a travesty of truth.

Other political researchers argued that traditional approach is mainly descriptive. Politics does not rule out description, but it is also analytical. Sheer description of facts does not inevitably establish the subject matter of political science. Its purpose is study the depth of every incident. Investigators want to know not only occurrence, but also why a particular incident occurs at a particular time.

The standpoint of the traditionalists is limited within the institutions. Political researchers in modern world are not motivated to limit their analysis of politics within institutions. They have explored the role of environment into which is included international politics multinational corporations, non-governmental organisations or trans-national bodies.

It is assumed that traditional analysis is inappropriate for all types of political systems both Western and non-Western. To recompense this deficiency, the political scientists of the post-Second World War period have developed a general system approach which is quite comprehensive. The outstanding feature of traditional approaches is that there is value laden system.

Introduction

Difference between comparative politics and comparative government is very subtle that they are often referred to as one. Studying the political system in terms of divisions, countries, and regions has had substantial history. Politics is the practice and theory related to governance- organized control of the human community which also describes the practice of distribution of power not only within a particular community but also with interrelating communities. Furthermore, a political system is a framework of practices within a particular political territory. That is to say, the political system of one country may (or sometimes may not) be different from that of another country or territory. The body with the political power of a particular territory is called a government.

What is Comparative Politics?

Comparative politics is a term referring to the study of political understanding of more than one nationstate or country in order to make precise comparisons. It is an area of study in politics that is largely discussed and studied all over the world. There are two main approaches to comparative politics: one being the cross national approach and the other being the area studies approach. The first type of approach involve simultaneous studying of a large number of nation-states in order to obtain a wider understanding of theories and their applications. The latter type of approach deals with an in-depth analysis of politics within a particular political territory, a state, a country, a nation-state, or a region of the world.

What is Comparative Government?

The comparative government is a sub-division of politics that systematically studies, analyses, and compares the nature of governments in a number of selected countries. A government is the topmost hierarchical body of governance in the country or a nation-state. Through the study of comparative government, different forms of governments encountered around the world are studied, analyzed, and compared with a view to understanding the differences and seeking any potential practices a country can learn from another and adapt.What is the difference between Comparative Politics and Comparative Government?

- Comparative politics is a wider body whereas comparative government is one of its sub-divisions.

- Comparative politics studies and compares different theories and political practices of countries or/and nation-states. Comparative government is the study, analysis, and comparison of different government systems around the world.

- Comparative politics is not only about the government; it encompasses studying political aspects in terms of governance, foreign policies, etc. However, comparative government only compares different forms of governmental bodies in the world.

Despite these differences mentioned, the terms comparative politics and comparative government are often referred together in the sense that if a university offers a course in this field, it would best be on comparative politics and government. They are not often separated when studied.

Introduction to Comparative Politics

Comparative politics is a subfield of political science that examines and compares political systems, institutions, processes, and behaviors across countries. Over time, the study of comparative politics has evolved significantly, transitioning from traditional approaches focused on descriptive and normative analysis to modern approaches emphasizing empirical and scientific methods. This evolution reflects shifts in the academic priorities of the discipline, influenced by broader intellectual trends and technological advancements.

Traditional Approach to Comparative Politics

1. Nature and Focus

The traditional approach to comparative politics dominated the field from its inception until the mid-20th century. This approach is primarily descriptive, normative, and historical, focusing on formal institutions and legal frameworks.

- Key Characteristics:

- Emphasis on formal institutions such as constitutions, legislatures, and judiciaries.

- Use of historical analysis to understand the evolution of political systems.

- Normative concerns with prescribing the “ideal” political system.

- Limited attention to informal political structures, behavior, or cultural influences.

- Scope: Comparative studies were often confined to the Western world, particularly European countries, reflecting a Eurocentric bias.

2. Theoretical Underpinnings

The traditional approach relied heavily on political philosophy and legal analysis. It drew inspiration from classical theorists such as Plato, Aristotle, and Montesquieu, who emphasized normative ideals over empirical realities.