Ancient History – 2nd Year

Paper – II (PYQs Soln.)

Unit I

Language/भाषा

The Dakshinapath Campaign of Samudragupta, one of the most celebrated rulers of the Gupta Empire (c. 335–375 CE), is a landmark event in Indian history. Often hailed as the “Napoleon of India” for his military prowess, Samudragupta’s southern campaign expanded Gupta influence and demonstrated his strategic acumen. This campaign not only asserted the political dominance of the Gupta Empire but also played a key role in fostering cultural and economic interactions between northern and southern India.

Historical Background and the Objectives of the Campaign

Samudragupta inherited the Gupta throne from his father, Chandragupta I, and was determined to establish himself as a paramount ruler over the Indian subcontinent. By the time of his ascension, the Gupta Empire was a dominant power in northern India. However, the fragmented political situation in the Deccan and the southern regions of India (referred to as Dakshinapatha) presented an opportunity for territorial expansion.

The primary objectives of the Dakshinapath Campaign were to:

- Assert the sovereignty of the Gupta Empire over key territories in the Deccan and southern India.

- Expand the Gupta influence beyond the Vindhya ranges.

- Secure alliances with southern rulers and establish a tributary system.

The Course of the Campaign

The Dakshinapath Campaign, meticulously chronicled in the Prayag Prashasti (Allahabad Pillar Inscription), penned by Samudragupta’s court poet Harisena, describes in detail the ruler’s conquests and victories.

Samudragupta marched southward with his powerful army, crossing the Vindhya ranges and penetrating into the Deccan plateau. He targeted a series of kingdoms in Dakshinapatha. The campaign can be divided into two phases:

Military Conquest

Samudragupta launched a series of battles against various rulers of southern India, subjugating them through military force. Harisena’s inscription lists twelve southern kingdoms defeated by Samudragupta during this campaign:

- Kosala (central India).

- Mahakantara and Kaurala (forested regions of central and eastern India).

- Devarashtra (present-day Maharashtra).

- Erandapalla (southern Maharashtra).

- Kanchi (Pallava kingdom, present-day Tamil Nadu).

- Avamukta, Pishtapura, Vengi, and Palakkad (eastern Andhra Pradesh region).

- Kottura and Damana (southern Karnataka region).

The rulers of these kingdoms were either killed, imprisoned, or subjugated, and they were compelled to acknowledge Samudragupta’s supremacy. Despite his military superiority, Samudragupta did not seek to annex these territories permanently. Instead, he allowed many of the defeated rulers to retain their kingdoms in exchange for their loyalty and tribute.

Diplomatic Subjugation

Unlike his campaigns in northern India, which involved direct annexation, Samudragupta adopted a more pragmatic approach in the south. After defeating the southern rulers, he reinstated them as tributaries. This strategic decision allowed him to avoid the logistical difficulties of administering distant territories while simultaneously projecting Gupta influence into southern India.

Key Features of the Dakshinapath Campaign

Military Genius

Samudragupta’s success in the Dakshinapath Campaign highlights his remarkable military leadership. The campaign involved crossing rugged terrains, including forests, mountains, and rivers, which posed logistical challenges. His ability to mobilize his army and execute swift, decisive campaigns demonstrated his strategic acumen.

Policy of Non-Annexation

A distinctive feature of the Dakshinapath Campaign was Samudragupta’s decision not to annex the southern territories. This policy underscores his understanding of the geographical and political realities of the Deccan. By transforming the southern kingdoms into tributary states, he established a network of alliances without overextending his empire.

Cultural Diplomacy

The campaign also facilitated cultural exchanges between northern and southern India. Samudragupta’s policy of reinstating the defeated rulers as tributaries fostered goodwill and ensured the flow of wealth, artisans, and scholars between the two regions. The Gupta influence on art, literature, and administrative practices extended into southern India as a result.

Consequences of the Campaign

The Dakshinapath Campaign significantly strengthened Samudragupta’s position as a paramount ruler and left an indelible mark on Indian history.

Political Supremacy

The campaign elevated Samudragupta’s status as a Chakravarti (universal ruler). By subjugating the southern kingdoms, he consolidated his authority over a vast territory stretching from the Himalayas to the Deccan. This political unification, albeit temporary, contributed to the Gupta Empire’s reputation as a pan-Indian power.

Economic Impact

The tribute extracted from the southern rulers brought immense wealth to the Gupta court. This economic prosperity funded cultural and architectural endeavors, contributing to the Golden Age of the Gupta Empire. Trade routes connecting northern and southern India became more secure, enhancing economic integration across the subcontinent.

Cultural and Religious Influence

The Dakshinapath Campaign facilitated the spread of Brahmanical culture, Sanskrit language, and Gupta-style art and architecture into southern India. This period saw the rise of Sanskrit inscriptions, temple construction, and the promotion of classical Hinduism in the Deccan and beyond. The Pallava rulers of Kanchi, for instance, were influenced by Gupta cultural and administrative practices.

Legacy

Samudragupta’s southern campaign is celebrated as a testament to his statesmanship and military prowess. The Dakshinapath Campaign set a precedent for later rulers who sought to unify the Indian subcontinent. It also underscored the importance of diplomacy and cultural exchange in building a legacy of influence that extended beyond territorial conquests.

Conclusion

The Dakshinapath Campaign of Samudragupta is a defining chapter in the history of the Gupta Empire. It exemplifies the ruler’s vision of creating a pan-Indian empire through a combination of military conquests and diplomatic alliances. By asserting Gupta influence over the southern kingdoms, Samudragupta not only consolidated his political supremacy but also fostered cultural integration and economic prosperity. The campaign stands as a testament to his unparalleled leadership and remains a key example of statecraft in ancient Indian history.

For nearly 250 years the Gupta empire provided political unity, good administration and economic and cultural progress to North India. The period, therefore, has been rightly regarded as the most glorious epoch in Indian history. But then it disappeared from the scene.

The difficulties of the empire began during the later period of the reign of Kumar Gupta I. Skanda Gupta faced them successfully but could not finish them. The difficulties were converted into weaknesses after him when his weak successors failed to rise to the occasion. This led to the disruption and finally to the extinction of the empire. The Gupta empire also met the fate of the Maurya empire and the causes too, more or less, were similar.

Skanda Gupta successfully checked the invasion of the Hunas as a crown- prince and as an emperor he inflicted a crushing defeat on them. He also succeeded in eliminating completely the threat posed by Pushyamitras to the empire from the South. Yet these campaigns heavily taxed the financial and military resources of the empire. Therefore, he was forced to lower the quality of his gold coins.

It meant that the empire was under financial strain. However, Skanda Gupta was successful. But. after him, the Gupta rulers proved incompetent. Their incompetence increased the number of internal and external enemies. The provincial governors began to assert independence right from the reign of Puru Gupta. Emperor Budha Gupta was hardly able to maintain a show of suzerainty over his governors.

After him even the nominal suzerainty was thrown off by the governors and they became independent rulers. The same way, the later Gupta rulers failed to face their external enemies like the Vakatakas and the Hunas. Thus, the incompetence of the Gupta rulers after Skanda Gupta was one of the primary causes of the downfall of the empire. In the absence of competent rulers no empire could be preserved in those times. The Guptas also lost their empire primarily because of their own incompetence.

Another factor which brought ruin to the Gupta rulers was their own internal dissensions. After Kumara Gupta the succession to the throne was always disputed. Probably, even Skanda Gupta had to fight against Pura Gupta to get the throne. And after the death of Pura Gupta the rival princes of the family of Skanda Gupta and Pura Gupta fought against themselves and the empire was divided.

Probably, for a few years, Narsimha Gupta ruled in Magadha while at the same time Vainya Gupta ruled over the eastern part of the empire and Bhanu Gupta ruled in the West. Budha Gupta who ascended the throne in 477 A.D. was not the ruler of a consolidated empire, but rather, the head of a federal state.

After him, even that semblance of unity was overthrown and different Gupta princes or rulers took opposite side in the struggles and political convulsions of their period. This, certainly, helped in bringing about the downfall of the empire.

Put together, the incompetence of the later Gupta rulers and their internal conflicts weakened the central authority which encouraged both external and internal enemies of the empire to take advantage of it. While the Vakataka-rulers and the Hunas endangered the Imperial territories from outside, the provincial governors broke up the unit} of the empire from within by asserting their independence.

The success of Yasodharmana in Malwa encouraged others. The Maitrakas assumed independence at Valabhi, the Maukharis created an independent kingdom in the upper Ganges valley and the Gandas wrested Bengal from the Guptas. The weak Gupta rulers failed to check the disintegration of the empire.

The Vakatakas had created a powerful kingdom in South-west. Samudra Gupta had not harmed them while Chandra Gupta II had entered into a matrimonial alliance with them by marrying his daughter Prabhavati to the then Vakataka ruler Rudrasen II. But when the Gupta empire weakened, the Vakataka rulers tried to take advantage of it.

Narendra Sen attacked the territories of the empire in Malwa, Kosala and Mekhala during the period of Budha Gupta which weakened the authority of the Guptas in Madhva Pradesh and Bundelkhand. Afterwards, the Vakataka ruler Hansen also attacked the boundaries of the empire. These attacks of the Vakataka rulers were primarily responsible for weakening the authority of the Guptas in Malwa. Gujarat and Bundelkhan 1 and encouraging their governors to assert their independence.

A few scholars have expressed the view that the invasions of the Hunas were primarily responsible for the downfall of the Gupta empire. But it is not generally accepted. The view expressed by Dr R.C. Majumdar is more tenable and now generally accepted. He says that the invasions of the Hunas were not primarily but only partially responsible for the downfall of the empire. The Hunas were defeated so severely by Skanda Gupta that they did not dare to invade the empire for about the next fifty years.

And, when they started their attacks again the empire had already become weak because of its internal dissensions. Of course, the Huna Kings Toramana and Mihirakula succeeded in penetrating deep into the Indian territories as far as the borders of Magadha. But then, at that time, they were not fighting against the lively and mighty Gupta empire but against its ghost. The mighty Gupta empire was already dead. At that time it existed only in name.

The Hunas did not contribute in any way to its death. In fact, they came when only the last ceremonies were due. Even then the Hunas were not very much successful in India because they, too, had lost their wave-strength by that time. The Kingdom of Toramana did not cross the river Indus and Mihirakula was defeated twice here, once by Narsiinha Gupta II and once by Yasodharman of Mandasor (Malwa).

Thus, the Hunas neither directly contributed to the downfall of the Gupta empire nor were they capable of it when they attempted it next time, once they were defeated by Skanda Gupta. However, it is accepted that their attacks, no doubt, put a heavy pressure on the financial and military resources of the empire and therefore, were partially responsible for its downfall.

Dr H.C. Raychaudhury puts forward a different reason for the downfall of the empire. He says that the later Gupta rulers were influenced by Buddhism and its principle of non-violence. This brought about a negative influence on their military strength and that also contributed, partially, to their downfall. Narsimha II was inclined towards Buddhism and it is stated that he once captured Mihirakula but left him free on the advice of his Buddhist mother.

Such acts cannot be justified in matters concerning state-politics and none would deny that the attitude of non-violence or passivity is harmful to the military strength of a state and, thus, creates danger to its existence. The later Gupta rulers definitely failed to maintain their military- strength and. thereby to pursue a forceful policy against their external enemies and internal dissenters which, certainly, resulted in the downfall of the empire.

After Budha Gupta, there existed virtually no Gupta empire as such. Narsimha Gupta was simply the ruler of Magadha. The rest of the empire was lost by him. Afterwards Magadha was also occupied by Maukhari ruler Isana- Varcnan near about 544 A.D. though it is believed that the Gupta rule existed in north Bengal up to 550 A.D. or so and in Kalinga till 569 A.D.

Thus, ended the mighty Gupta empire. The internal weakness of the empire was primarily responsible for its downfall though, of course, external attacks also contributed to it. Dr R.C. Majumdar rightly concludes, “Indeed, from various points of view the end of the Gupta empire offers a striking analogy to that of the Mughal empire. The decline and downfall of both was brought about mainly by internal dissensions in royal family and the rebellion of feudal chiefs and provincial satraps, though foreign invasion was an important contributory factor.”

Chandragupta II, also known as Vikramaditya, is regarded as one of the greatest rulers of the Gupta dynasty. Chandragupta II was the son of Samudragupta and Datta Devi. According to historical records, Chandragupta II was a strong, vigorous ruler who was well qualified to govern and expand the Gupta Empire. He ruled the Gupta Empire from 380 to 412 C.E., during the Golden Age of India. Based on coins and a supia pillar inscription, it is believed that Chandragupta II adopted the title ‘Vikramaditya.’

Features

- Chandragupta II (c. 380 – c. 412 CE), also known as Vikramaditya and Chandragupta Vikramaditya, was the third ruler of India’s Gupta Empire and one of the dynasty’s most powerful emperors.

- Chandragupta carried on his father’s expansionist policy, primarily through military conquest.

- He defeated the Western Kshatrapas and expanded the Gupta Empire from the Indus River in the west to the Bengal region in the east, and from the Himalayan foothills in the north to the Narmada River in the south, according to historical evidence.

- Prabhavatigupta, his daughter, was queen of the southern Vakataka kingdom, and he may have had influence in the Vakataka territory during her regency.

- During Chandragupta’s reign, the Gupta Empire reached its pinnacle. According to the Chinese pilgrim Faxian(Fa-Hien), who visited India during his reign, he ruled over a peaceful and prosperous kingdom.

- The legendary Vikramaditya is most likely based on Chandragupta II (among other kings), and the noted Sanskrit poet Kalidasa may have served as his court poet.

Names and Titles

- Chandragupta II was the dynasty’s second ruler to bear the name “Chandragupta,” following his grandfather Chandragupta I. As evidenced by his coins, he was also known simply as “Chandra.”

- According to his officer Amrakardava’s Sanchi inscription, he was also known as Deva-raja. His daughter Prabhavatigupta’s records, issued as a Vakataka queen, refer to him as Chandragupta as well as Deva-gupta.

- Another spelling of this name is Deva-shri. According to the inscription on the Delhi iron pillar, King Chandra was also known as “Dhava.”

- Chandragupta was given the titles Bhattaraka and Maharajadhiraja, as well as the moniker Apratiratha (“having no equal or antagonist”).

- The Supiya stone pillar inscription, which was commissioned during the reign of his descendant Skandagupta, also refers to him as “Vikramaditya.”

Background

- According to his own inscriptions, Chandragupta was the son of Samudragupta and queen Dattadevi.

- Chandragupta succeeded his father on the Gupta throne, according to the official Gupta genealogy. The Sanskrit play Devichandraguptam, along with other evidence, suggests that he had an elder brother named Ramagupta who ascended to the throne before him.

- When Ramagupta is besieged, he decides to surrender his queen Dhruvadevi to a Shaka enemy, but Chandragupta disguises himself as the queen and kills the enemy.

- Later, Chandragupta dethrones Ramagupta and ascends to the throne.

- Modern historians debate the historicity of this narrative, with some believing it is based on true historical events and others dismissing it as a work of fiction.

Military Career

- The Udayagiri inscription of Chandragupta’s foreign minister Virasena suggests that the king had a distinguished military career. It is stated that he “bought the earth,” paying for it with his prowess, and reduced the other kings to the status of slaves.

- His empire appears to have stretched from the mouth of the Indus and northern Pakistan in the west to the Bengal region in the east, and from the Himalayan terai region in the north to the Narmada River in the south.

- The Ashvamedha horse sacrifice was performed by Chandragupta’s father, Samudragupta, and his son, Kumaragupta I, to demonstrate their military prowess.

- The discovery of a stone image of a horse near Varanasi in the twentieth century, and the misreading of its inscription as “Chandramgu” (taken to be “Chandragupta”), led to speculation that Chandragupta also performed the Ashvamedha sacrifice. However, no actual evidence exists to support this theory.

Conquests

Western Kshatrapas

- According to historical and literary evidence, Chandragupta II had military victories against the Western Kshatrapas (also known as Shakas), who ruled in west-central India.

- The “Shaka-Murundas” are mentioned among the kings who tried to appease Chandragupta’s father Samudragupta in the Allahabad Pillar inscription.

- Samudragupta may have reduced the Shakas to a subordinate alliance, and Chandragupta completely subjugated them.

- The Western Kshatrapas was the only significant power to rule in this region during Chandragupta’s reign, as evidenced by their distinct coinage. The Western Kshatrapa rulers’ coinage abruptly came to an end in the last decade of the fourth century.

- This type of coin reappears in the second decade of the fifth century and is dated in the Gupta era, implying that Chandragupta subjugated the Western Kshatrapas.

Punjab

- Chandragupta appears to have marched through the Punjab region and up to the Vahlikas’ country, Balkh in modern-day Afghanistan.

- Some short Sanskrit inscriptions in Gupta script at the Sacred Rock of Hunza (in modern-day Pakistan) mention the name Chandra.

- Several of these inscriptions mention the name Harishena, and one mentions Chandra with the epithet “Vikramaditya.” Based on the identification of “Chandra” with Chandragupta and Harishena with Gupta courtier Harishena, these inscriptions can be regarded as additional evidence of a Gupta military campaign in the area.

- This identification, however, is not certain, and Chandra of the Hunza inscriptions could have been a local ruler.

- The phrase “seven faces” mentioned in the iron pillar inscription refers to Indus’ seven mouths. The term is thought to refer to the Indus tributaries: the five rivers of Punjab (Jhelum, Ravi, Sutlej, Beas, and Chenab), as well as the Kabul and Kunar rivers.

- It is quite possible that Chandragupta passed through the Punjab region during this campaign: the use of the Gupta era in an inscription found at Shorkot, as well as some coins bearing the name “Chandragupta,” attest to his political influence in this region.

Bengal

- The identification of Chandra with Chandragupta II also implies that Chandragupta won victories in the Vanga region of modern-day Bengal.

- According to his father Samudragupta’s Allahabad Pillar inscription, the Samatata kingdom of the Bengal region was a Gupta tributary.

- The Guptas are known to have ruled Bengal in the early sixth century CE, but there are no records of their presence in this region during the intervening period.

- It is possible that Chandragupta annexed a large portion of the Bengal region to the Gupta empire, and that this control lasted into the sixth century.

- According to the inscription on the Delhi iron pillar, an alliance of semi-independent Bengal chiefs unsuccessfully resisted Chandragupta’s attempts to extend Gupta influence in this region.

Matrimonial Alliance

- According to Gupta records, Dhruvadevi was Chandragupta’s queen and the mother of his successor Kumaragupta I. Dhruva-svamini is mentioned on the Basarh clay seal as a Chandragupta queen and the mother of Govindagupta.

- It appears that Dhruvasvamini was most likely another name for Dhruvadevi, and that Govindagupta was Kumaragupta’s uterine brother.

- Chandragupta also married Kuvera-naga (alias Kuberanaga), whose name indicates that she was a princess of the Naga dynasty, which held considerable power in central India before Samudragupta subjugated them.

- This matrimonial alliance may have aided Chandragupta in consolidating the Gupta empire, and the Nagas may have aided him in his war against the Western Kshatrapas.

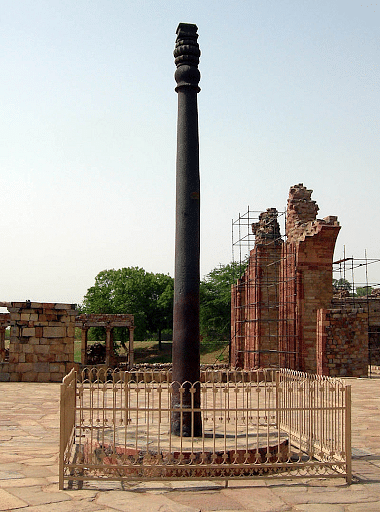

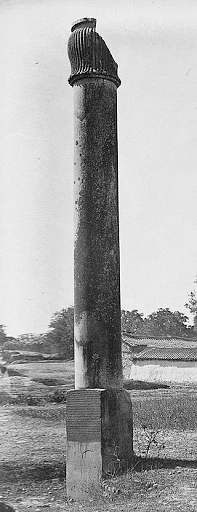

Mehrauli Iron Pillar

- Close to the Qutub Minar stands one of Delhi’s most unusual structures, an iron pillar with an inscription declaring that the pillar was created by artisans in the fourth century C.E. in honour of Hindu God Vishnu and in memory of Chandragupta II.

- The Mehrauli Iron Pillar was originally located on a hill near Beas, and it was brought to Delhi by Radhakumud Mookerji, a king of the Gupta Empire. This pillar attributes the following to Chandragupta II (Vikramaditya):

- Conquest of the Vanga countries when he fought alone against an enemy alliance.

- Valakas was defeated in a battle that spanned Sindhu’s seven mouths.

- Spread Chandragupta II’s fame to the southern seas.

- He attained Ekadhirajjyam through the prowess of his arms .

- He named the Mehrauli Iron Pillar Vishnupasa in honour of the Hindu God Vishnu.

Iron Pillar in Delhi

Sanchi Inscription

- The Chandragupta II Sanchi inscription is an epigraphic record that documents a donation to the Buddhist establishment at Sanchi during the reign of King Chandragupta II.

- It is from the Gupta era and dates from the year 93.

- Sanchi is located in Madhya Pradesh’s Raisen District.

- The inscription is located on the railing of the main stupa, immediately to the left of the eastern gate.

Inscription of Chandragupta II at Sanchi

Administration

Several feudatories of Chandragupta are known from historical records:

- Maharaja Sanakanika, a feudatory whose construction of a Vaishnava temple is recorded in the Udayagiri inscription.

- Maharaja Trikamala, a feudatory known from a Gaya inscription engraved on a Bodhisattva image.

- Maharaja Shri Vishvamitra Svami, a feudaotry known from a seal discovered in Vidisha.

- Maharaja Svamidasa, the ruler of Valkha, was also most likely a Gupta feudatory; is dated in the Kalachuri calendar era.

Various historical records identify the following Chandragupta ministers and officers:

- Vira-Sena, Foreign minister is known from the Udayagiri inscription, which records his construction of a Shiva temple.

- Amrakardava, a military officer, is remembered in the Sanchi inscription for his contributions to the local Buddhist monastery.

- Shikhara-svami was a minister who wrote the political treatise Kamandakiya Niti.

Navratnas

Chandragupta II was known for his deep interest in art and culture, and his court was adorned with nine gems known as Navratna. The diverse fields of these 9 gems demonstrate Chandragupta’s patronage of the arts and literature. The following is a brief description of the nine Ratnas:

- Amarsimha: Amarsimha was a Sanskrit poet and lexicographer, and his Amarkosha is a vocabulary of Sanskrit roots, homonyms, and synonyms. It is also known as Trikanda because it is divided into three sections: Kanda 1, Kanda 2, and Kanda 3. It contains ten thousand words.

- Dhanvantri: Dhanvantri was an excellent physician.

- Harisena: Harisena is credited with writing the Prayag Prasasti, or Allahabad Pillar Inscription. The title of Kavya’s inscription, but it contains both prose and verse. The entire poem is in one sentence, including the first eight stanzas of poetry, a long sentence, and a concluding stanza. In his old age, Harisena was in the court of Chandragupta and describes him as Noble, asking him, “You Protect all this earth.”

- Kalidasa: Kalidasa is India’s immortal poet and playwright, and a peerless genius whose works have become famous throughout the world in the modern era. The translation of Kalidasa’s works into numerous Indian and foreign languages has spread his fame throughout the world, and he now ranks among the top poets of all time. Rabindranath Tagore not only popularised Kalidasa’s works but also elaborated on their meanings and philosophy, making him an immortal poet and dramatist.

- Kahapanaka: Kahapanka was an astrologer. There aren’t many details available about him.

- Sanku: Sanku worked in architecture.

- Varahamihira: Varahamihira (d. 587) was a Ujjain resident who wrote three important books: Panchasiddhantika, Brihat Samhita, and Brihat Jataka. The Surya Siddhanta is included in the Panchasiddhantaka, which is a summary of five early astronomical systems. Another system he describes, the Paitamaha Siddhanta, appears to share many similarities with Lagadha’s ancient Vedanga Jyotisha. Brihat Samhita is a collection of topics that provide interesting details about the beliefs of the time. Brihat Jataka is an astrology book that appears to be heavily influenced by Greek astrology.

- Vararuchi: Vararuchi is the name of another gem of Chandragupta Vikramaditya, a grammarian and Sanskrit scholar. Some historians have linked him to Katyayana. Vararuchi is credited with writing the first Grammar of the Prakrit language, Prakrit Prakasha.

- Vetalbhatta: Vetalbhatta was a magician.

Religion

- Many of Chandragupta’s gold and silver coins, as well as the inscriptions issued by him and his successors, describe him as a parama-bhagvata, or devotee of the god Vishnu.

- One of his gold coins, discovered at Bayana, refers to him as chakra-vikramah, which translates as “[one who is] powerful [due to his possession of the] discus,” and depicts him receiving a discus from Vishnu.

- In the year 82 of the Gupta era, Chandragupta’s feudatory Maharaja Sanakanika built a Vaishnava cave temple, according to an Udayagiri inscription.

- Chandragupta was also accepting of other religions. The Udayagiri inscription of Chandragupta’s foreign minister Virasena records the construction of a temple dedicated to the god Shambhu (Shiva).

- In the year 93 of the Gupta era(c. 412-413 CE), his military officer Amrakardava made donations to the local Buddhist monastery, according to an inscription discovered near Udayagiri .

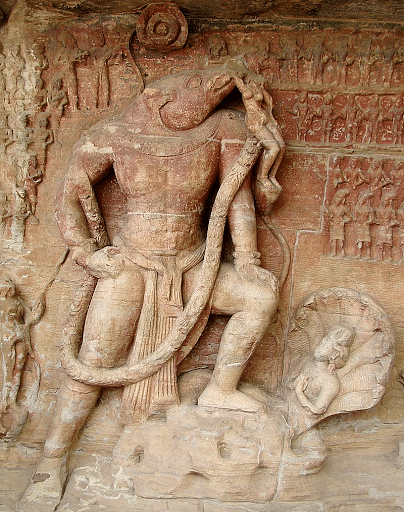

Development of Vaishnavism in India, and the establishment of the Udayagiri Caves with Vaishnava iconography

Coinage

- Most of the gold coin types introduced by his father Samudragupta were continued by Chandragupta, including the Sceptre type, the Archer type, and the Tiger-Slayer type.

- However, Chandragupta II also introduced several new types, including the Horseman and Lion-slayer types, which were used by his son Kumaragupta I.

- Chandragupta’s gold coins depict his martial spirit as well as his peacetime pursuits.

Gold coin of Chandragupta II

Fa-Hien’s Visit

- Pataliputra was largely ignored by warrior kings such as Samudragupta and Vikramaditya, but it remained a magnificent and populous city throughout Chandragupta II’s reign.

- Patliputra was later reduced to reigns following the Hun invasions in the sixth century. Shershah Suri, on the other hand, rebuilt and revitalized Pataliputra as today’s Patna.

- Fa Hien’s accounts provide a contemporary account of Chandragupta Vikramaditya’s administration. Fa Hien (337 – ca. 422 AD) was so engrossed in his search for Buddhist books, legends, and miracles that he couldn’t recall the name of the mighty monarch under whose rule he had lived for 6 years.

- He saw and was impressed by Asoka’s palace at Pataliputra, so it is certain that Asoka’s palace existed even during the Gupta era. He also mentions a stupa and two monasteries nearby, both of which are attributed to Asoka.

- He mentioned 600-700 monks living there and receiving lectures from teachers from all over. He mentions that the towns of Magadha were the largest in the area of the Gangetic Plains, which he refers to as central India.

- Fa Hien goes on to say that the people of the western part (Malwa) were content and unconcerned. He mentions that they are not required to register their household or appear before a magistrate. People did not lock their doors. The passports, and those who wanted to stay or go, did not bind them.

- Fa Hien goes on to say that no one kills living things, drinks wine, or eats onion or garlic. There are no pigs or fowls, no cattle trading, and no butchers. All of this was done by Chandals alone.

- Fa Hien studied Sanskrit without interruption for three years at Pataliputra and two years at the Port of Tamralipti. The roads were clear and safe for the passengers to travel on.

- The accounts of Fa Hien show that India was probably never better governed than during the reign of Chandragupta Vikramaditya.

- The account of Fa-Hien and his unobstructed itinerary all around gives details about the Golden Era of Mother India, attesting to the prosperity of the Indians and the tranquillity of the empire.

Conclusion

Chandragupta II, a powerful and energetic ruler, was well-suited to rule over a vast empire. Kumaragupta I, also known as Mahedraditya, succeeded Chandragupta II. His reign lasted 40 years and was assigned to him during the years 415-455 AD. He was a capable ruler, and there is no doubt that his empire grew rather than shrank.

Skandagupta (r. 455–467) was an Indian Gupta Emperor. According to the inscription on his Bhitari pillar, he restored Gupta supremacy across the subcontinent by defeating his enemies, who could have been rebels or foreign invaders. He repelled an invasion by the Indo-Hephthalites (known as Hunas in India), who were most likely the Kidarites. He appears to have kept control of his inherited territory and is widely regarded as the last of the great Gupta Emperors. The Gupta genealogy after him is unclear, but he was most likely succeeded by Purugupta, his younger half-brother.

Features

- Skandagupta was a Gupta Emperor from northern India. Skandagupta was the son of Gupta emperor Kumaragupta I.

- He ascended to the throne in 455 AD and reigned until 467 AD.

- Skandagupta demonstrated his ability to rule by defeating Pushyamitras during his early years in power, earning the title of Vikramaditya.

- During his 12 year reign, he not only defended India’s great culture, but also defeated the Huns, who had invaded India from the north west.

- He is widely regarded as the final of the great Gupta Emperors.

Background

- Skandagupta was the son of Kumaragupta I, the Gupta emperor. His mother could have been a junior queen of Kumaragupta’s concubine.

- This theory is based on the fact that Skandagputa’s inscriptions mention his father’s name but not his mother’s.

- Skandagupta’s Bhitari pillar inscription, for example, names the chief queens (mahadevis) of his ancestors Chandragupta I, Samudragupta, and Chandragupta II but not his father Kumaragupta.

- Some scholars believe that Devaki was his mother’s name based on the inscription.

Ascension to the Throne

- Skandagupta ascended to the throne in the year 136 of the Gupta era. According to the Bhitari pillar inscription, he restored “his family’s fallen fortunes.”

- He prepared for this, according to the inscription, by sleeping on the ground for a night and then defeating his enemies, who had grown wealthy and powerful.

- After defeating his opponents, he went to see his widowed mother, who was crying “tears of joy.”

- His mother was most likely Kumaragupta’s junior wife, not the chief queen, and thus his claim to the throne was illegitimate.

- According to the Junagadh inscription, the goddess of fortune, Lakshmi, chose Skandagupta as her husband after rejecting all other “sons of kings.”

- Skandagupta’s coins depict a woman presenting him with an unidentified object, most likely a garland or ring.

- Following Kumaragupta’s death, it is said that several people in the Gupta empire assumed sovereign status. Kumaragupta’s brother, Govindagupta, is among them.

Conflict with the Huns

- The Indo-Hephthalites (also known as the White Huns or Hunas) invaded India from the northwest during Skandagupta’s reign, advancing as far as the Indus River.

- Skandagupta defeated the Huns, according to the inscription on the Bhitari pillar.

- The date of the Hun invasion is unknown. It is mentioned in the Bhitari inscription after describing the conflict with the Pushyamitras (or the Yudhyamitras), implying that it occurred later during Skandagupta’s reign.

- However, a possible reference to this conflict in the Junagadh inscription suggests that it occurred at the start of Skandagupta’s reign or during his father Kumaragupta’s reign.

- The Junagadh inscription, dated to the Gupta era’s year 138 (c. 457- 458 CE), mentions Skandagupta’s victory over the mlechchhas (foreigners).

- The victory over the mlechchhas occurred in or around the year 136 of the Gupta era (c. 455 – 456 CE), when Skandagupta ascended to the throne and appointed Parnadatta as governor of the Saurashtra region, which included Junagadh.

- Because Skandagupta is not known to have fought any other foreigners, these mlechchhas were most likely Hunas.

- If this identification is correct, it is possible that Skandagupta was sent as a prince to check the Huna invasion at the border, and Kumaragupta died in the capital while this conflict was going on; Skandagupta returned to the capital and defeated rebels or rival claimants to ascend the throne.

Bhitari Pillar Inscription of Skandagupta

- Skandagupta’s Bhitari pillar inscription was discovered in Bhitari, Saidpur, Ghazipur, Uttar Pradesh, during the reign of Gupta Empire ruler Skandagupta (c. 455 – c. 467 CE).

- The inscription is extremely important in understanding the chronology of the various Gupta rulers, among other things. It also mentions Skandagupta’s conflict with the Pushyamitras and the Hunas.

- The inscription is written in 19 lines, beginning with a genealogy of Skandagupta’s ancestors, followed by a presentation of Skandagupta himself, and finally a presentation of his achievements.

Bhitari Pillar and Inscription

Western India

- The inscription on the Junagadh rock, which contains inscriptions of earlier emperors Ashoka and Rudradaman, was engraved on the orders of Skandagupta’s governor Parnadatta.

- According to the inscription, Skandagupta appointed governors for all provinces, including Parnadatta as governor of Surashtra.

- It is unclear whether the verse refers to routine appointments made by the king or his actions following a political upheaval caused by a war of succession or invasion.

- The inscription lists several qualifications for the governorship of Surashtra, stating that only Parnadatta possessed these qualifications.

- Again, it’s unclear whether these were actual qualifications for being a governor under Skandagupta’s rule, or if the verse is simply meant to praise Parnadatta.

- Parnadatta appointed his son Chakrapalita as magistrate of Girinagara (near modern Junagadh-Girnar), presumably the capital of Surashtra.

Coinage

- Samudragupta issued fewer gold coins than his predecessors, and some of these coins contain a smaller amount of gold. It is possible that the various wars he fought strained the state treasury, but this cannot be proven.

- Skandagupta issued five different types of gold coins: Archer, King and Queen, Chhatra, Lion-slayer, and Horseman type. His silver coins come in four varieties: Garuda, Bull, Altar, and Madhyadesha type.

- The initial gold coinage was based on his father Kumaragupta’s old weight standard of approximately 8.4 gm. This initial coinage is extremely rare.

- Skandagupta revalued his currency at some point during his reign, switching from the old dinar standard to a new suvarna standard weighing approximately 9.2 gm.

- These later coins were all of the Archer type, and all subsequent Gupta rulers followed this standard and type.

Skandagupta coin in Western Satraps style

Skandagupta’s coin facing Garuda

Conclusion

Skandagupta’s last known date is 467-468 CE (year 148 of the Gupta era), but he most likely ruled for a few more years. Skandagupta was most likely succeeded by Purugupta, who appears to be his half-brother. Purugupta was Kumaragupta I’s son from his chief queen and thus his legitimate successor. It is possible that he was a minor at the time of Kumaragupta I’s death, which allowed Skandagupta to ascend the throne. Skandagupta appears to have died heirless, or his son may have been dethroned by Purugupta’s family.

Samudragupta, a prominent character in ancient Indian history, ascended to power as king of the Gupta Empire in 335 CE, succeeding his father Chandragupta I. Samudragupta, known for his military strength and diplomatic intelligence, led a series of victories and expansions that established Gupta rule over the Indian subcontinent. His rule was marked by a golden age of cultural prosperity, with the encouragement of the arts, literature, and study, establishing the Gupta Empire as a symbol of civilization and intellectual life in South Asia.

Conquest of Samudragupta

The following describes the military conquest of Samudragupta:

North Indian Campaign

The first year of his reign was to subjugate the provinces of the Ganges under a plan called “Aryavarta”.He twice led his campaigns to the north; In the first Samudragupta vanquished three kings and in the second, he defeated nine kings. He seems to have made his way to Chambal, killed all the kings of the region, and made his region a part of the Gupta Empire. As mentioned in the 14-21 lines of Prayag Prasasthi, Samudragupta attacked and defeated the ruler of the upper Ganges valley (probably the unknown king Kota in the Bulandshahr region) and then defeated nine kings in northern India.

According to the Allahabad inscription, during his northern campaigns, he defeated nine kings and annexed them to his kingdom and he called it “Digvijay”. He defeated nine kings of Aryavarta: Nandin, Balavarman, Nagasena, Rudradeva, Chandravarman, Mathila, Gangapathinaga, Nagadatta and Achyuta.

South Indian Campaign

After consolidating his power in the north, Samudragupta turned his attention to the south and launched an expedition, and his army travelled some 3,000 miles. He defeated the twelve kings of South India. But he put it back. These kings became their trap and agreed to get respect. He called it “Dharmavijay”.

Samudragupta defeated 12 kings of South India are:

- Mahendra of Kosala

- Vyagraraja of Mahakantara

- Mantharaja of Kowrala

- Mahendra of Pistapura

- Swamydatta of Kottura

- Damana of Yarandapalli

- Vishnugopa of Kanchi

- Hastivarman of Vengi

- Neelaraja of Avamukta

- Ugrasena of Palakkad

- Kubera of Devarashtra

- Dhananjaya of Kustalapura.

Campaign to the Forest and Tribal Areas

Having conquered the northern and the southern states, Samudragupta moved towards the tribal and the forest areas. It is presently located in Jabalpur and Deccan, Madhya Pradesh. The Line 22 of the Allahabad Prashasti provides the details of his campaign and states that the kings of the forest kingdom were enslaved as well as the defeated kings were appointed by the Gupta emperor to rule their territory.

Conquest of Border States

Samudragupta’s conquest of the border states was a strategic effort to increase Gupta dominance and secure the empire’s borders. He conquered adjacent kingdoms and territory in a series of military expeditions, expanding Gupta dominion to the Himalayas, the Deccan Plateau, and beyond. These victories not only strengthened the Gupta Empire’s territorial control, but also facilitated trade routes, promoted cultural interaction, and reinforced Gupta dominance over varied ethnic and geographical settings.

Territorial Expansion and Administration of Samudragupta

Samudragupta’s territorial expansion and administration were essential for the establishment and control of the Gupta Empire. Through smart military battles and diplomatic agreements, he extended Gupta power over the Indian subcontinent, from the Himalayas to the Deccan Plateau.

- Once territories were conquered, Samudragupta implemented effective administrative policies to rule the diverse regions under Gupta control. He established administrative centers, appointed governors, and enacted laws to ensure efficient governance and maintain order.

- Samudragupta’s administration was characterized by a decentralized system that allowed local rulers a degree of autonomy while remaining loyal to the central authority of the Gupta Empire.

- Also, Samudragupta’s administration encouraged economic prosperity and cultural exchange by promoting trade, agriculture, and the arts. His patronage of literature, philosophy, and the sciences contributed to a flourishing of intellectual and cultural life within the empire.

- Overall, Samudragupta’s territorial expansion and administration were important in transforming the Gupta Empire into a strong political and cultural force in ancient India, leaving a legacy of imperial governance and cultural achievement that lasted for centuries.

Achievements of Samudragupta

Samudragupta’s achievements are varied, including:

- Military Conquests: Samudragupta expanded the Gupta Empire through a series of successful military campaigns, conquering several kingdoms and territories across the Indian subcontinent.

- Territorial Expansion: Under his rule, the Gupta Empire reached its peak, extending its borders from the Himalayas to the Deccan Plateau and from the Arakanese coast to present-day Gujarat.

- Diplomatic Skill: Samudragupta’s diplomacy and statesmanship enabled him to form alliances, sign peace treaties, and preserve internal stability inside his empire, resulting in an era of relative peace and prosperity.

- Patronage of Arts and Culture: He was a great patron of the arts, literature, and learning, attracting scholars, poets, and intellectuals to his court and encouraging a golden age of Indian civilization.

- Cultural Influence: Samudragupta’s reign witnessed major advancements in literature, philosophy, and the arts, contributing to the development of classical Indian culture and thought.

- Administrative Reforms: He implemented effective administrative policies and systems to rule the vast territories of the Gupta Empire, promoting efficient governance and economic prosperity.

- Legacy: Samudragupta’s achievements established the Gupta Empire as the dominating political and cultural power in ancient India, leaving an impact that influenced the direction of Indian history for centuries.

Digvijay Policy of Samudragupta

The Digvijay Policy of Samudragupta was a strategic approach to conquest characterized by the ambition to achieve universal dominance. Under this policy, Samudragupta aimed to conquer all directions or “digvijaya,” including the entire Indian subcontinent. He attempted to increase Gupta’s authority and establish dominance over surrounding kingdoms and territory through a series of military operations and diplomatic moves. This strategy allowed Samudragupta to consolidate and extend Gupta’s dominance, resulting in the empire’s territorial expansion and increased political and military power. The Digvijay Policy expresses Samudragupta’s vision of imperial conquest and his desire to establish the Gupta Empire as the dominant force in ancient India.

Samudragupta’s Legacy and Impact on Indian History

Samudragupta’s had a great legacy and influence on Indian history. As one of ancient India’s greatest monarchs, his achievements had a lasting impact on the subcontinent’s cultural, political, and social landscape.

- Samudragupta’s military conquests and territorial expansion greatly enlarged the boundaries of the Gupta Empire, establishing it as one of the largest and most powerful empires of its time. His reign marked the peak of Gupta power and influence.

- Under Samudragupta’s patronage, the Gupta Empire experienced a golden age of cultural and intellectual achievement. His support for the arts, literature, and learning attracted scholars, poets, and intellectuals to his court, encouraging a climate of creativity and innovation.

- Samudragupta’s diplomacy and statesmanship enabled him to craete alliances, negotiate treaties, and maintain stability within his empire. His ability to balance military might with diplomatic finesse contributed to the Gupta Empire’s longevity and prosperity.

- Samudragupta’s administrative reforms laid the foundation for efficient governance and economic prosperity within the Gupta Empire. His decentralized system of administration allowed for local autonomy while preserving centralized authority, promoting stability and unity.

- Samudragupta’s reign is remembered in Indian history as a time of exceptional success and glory. His conquests, administration, and support of the arts continue to attract praise and academic research.

Conclusion

In conclusion, Samudragupta’s conquests and expansion show his outstanding leadership and intelligence. He built the Gupta Empire into a powerful political and cultural force in ancient India by conducting smart military battles, negotiating diplomatically, and implementing administrative changes. His territorial expansion, cultural patronage, and diplomatic prowess left a legacy of imperial power and cultural development that lasted for centuries. Samudragupta’s reign reflects a golden age of affluence and awakening, one that has left a lasting impression on India’s history. As we consider his conquests and achievements, we are reminded of one of India’s greatest rulers’ lasting legacy, as well as the significant impact of his reign on the evolution of Indian civilization.

The Gupta Empire (c. 320–550 CE) is considered one of the most significant dynasties in Indian history, often referred to as the “Golden Age” due to its remarkable achievements in politics, culture, art, and science. The early history of the Gupta dynasty, leading up to the reign of Chandragupta I, lays the foundation for the empire’s later glory. The origins of the Guptas reflect a story of gradual rise from a modest regional power to a dominant force in northern India.

Origins of the Guptas

The Guptas originated as a minor ruling family in the region of Magadha (modern-day Bihar) and possibly Uttar Pradesh. Historical accounts suggest that their early power base was located in or around the fertile Ganges Valley, a region that had long been the heartland of ancient Indian civilizations.

Unlike earlier dynasties like the Mauryas and Kushanas, the Guptas began with a modest background, possibly as vassals or local chieftains. Their rise to power was characterized by careful alliances, conquests, and consolidation. While their precise ethnic and geographical origins remain uncertain, inscriptions and coins provide evidence of their gradual ascent.

The first significant figure of the dynasty is Sri Gupta, regarded as the founder of the Gupta lineage. Sri Gupta, whose reign is dated to the late 3rd century CE, likely ruled over a small territory in eastern India. His status as a “Maharaja” (great king) suggests that he exercised sovereignty, albeit on a limited scale. Not much is known about his reign, but he laid the groundwork for the dynasty’s expansion.

Ghatotkacha: The Transitional Leader

Sri Gupta was succeeded by his son, Ghatotkacha, who is also referred to as a “Maharaja” in inscriptions. Ghatotkacha’s reign appears to have been transitional, as he consolidated the gains made by his father while maintaining the Gupta lineage’s autonomy. Like his predecessor, he likely ruled a small kingdom in Magadha, strategically positioned to benefit from the economic and cultural vitality of the region.

Ghatotkacha’s leadership helped stabilize the dynasty, preparing it for greater expansion under his son, Chandragupta I. Although his reign did not witness significant territorial expansion, Ghatotkacha’s contributions were critical in ensuring a secure power base for his successors.

Chandragupta I: Architect of Gupta Ascendancy

The reign of Chandragupta I (c. 320–335 CE) marked a turning point in the early history of the Gupta dynasty. Under his leadership, the Guptas transitioned from a minor regional power to an emerging empire, setting the stage for the dynasty’s dominance in northern India.

Royal Title and Political Ambitions

Chandragupta I adopted the grand title of “Maharajadhiraja” (King of Kings), reflecting his ambition to position the Guptas as a major power. This title signified a new phase in the dynasty’s history, as it projected a sense of imperial authority and legitimacy.

Marriage Alliance with the Licchavis

One of Chandragupta I’s most significant achievements was his marriage alliance with the Licchavis, an influential ruling family of north Bihar. Chandragupta married Kumaradevi, a Licchavi princess, and this union proved to be a masterstroke in Gupta statecraft. The Licchavis controlled fertile territories and trade routes in the Gangetic plain, and their support provided Chandragupta with substantial resources and political legitimacy. Coins issued during Chandragupta’s reign depict him alongside Kumaradevi, emphasizing the importance of this alliance.

Territorial Expansion

While the Guptas remained centered in Magadha, Chandragupta I expanded the dynasty’s influence westward and northward. This expansion established Gupta control over key regions such as Prayaga (modern Allahabad), which would later become a strategic and cultural hub of the empire.

Significance of Early Gupta Rulers

The early Gupta rulers—Sri Gupta, Ghatotkacha, and Chandragupta I—played critical roles in laying the foundation of the empire’s later greatness. They demonstrated remarkable foresight in consolidating their power in Magadha, strategically leveraging alliances, and carefully expanding their territories. Their leadership ensured political stability and economic prosperity, enabling the dynasty to flourish in subsequent generations.

Economic Foundations

The early Guptas capitalized on the rich agricultural productivity of the Ganges Valley. This region had long been a center of trade, commerce, and cultural exchange. By securing control over this area, the Guptas positioned themselves as inheritors of the Mauryan legacy, ensuring a steady flow of revenue to sustain their growing state.

Cultural Developments

While the early Gupta rulers were primarily focused on political consolidation, their era also marked the beginning of cultural and artistic expressions that would define the Gupta “Golden Age.” The Gupta court patronized scholars and religious institutions, setting a precedent for the intellectual and cultural achievements of later reigns.

Legacy of Chandragupta I

Chandragupta I’s reign concluded with the transfer of power to his son, Samudragupta, whose military and administrative brilliance would elevate the Gupta Empire to its zenith. However, Chandragupta I’s contributions should not be understated. By forging strategic alliances, adopting imperial titles, and expanding Gupta influence, he laid the groundwork for the dynasty’s transformation into a pan-Indian empire.

In conclusion, the early history of the Guptas reflects their remarkable rise from obscurity to prominence. The contributions of Sri Gupta, Ghatotkacha, and Chandragupta I provided the political stability, economic resources, and strategic alliances necessary for the dynasty’s later achievements. Chandragupta I, in particular, stands out as a visionary leader whose efforts established the framework for the Gupta Empire’s Golden Age, a period that would define classical Indian civilization for centuries.