Medieval & Modern – 2nd Year

Paper – II (PYQs Soln.)

Part B

Unit I

Language/भाषा

The Government of India Act of 1858, also known as the Act for the Better Government of India, was a landmark piece of legislation passed by the British Parliament that marked a significant shift in Indian governance. It effectively ended the British East India Company’s rule over India and transferred administration to the British Crown.

The Government of India Act of 1858 established the British Raj, which lasted until India’s independence in 1947. The Act was a response to the Indian Rebellion of 1857, recognising the need for a more direct and centralised form of government.

What is the Government of India Act 1858?

The Government of India Act 1858, passed by the British Parliament on August 2, 1858, transferred authority over India from the East India Company to the British Crown. This shift was proposed due to flaws in the existing governance system, initially by Prime Minister Lord Palmerston. After Palmerston’s resignation, Edward Stanley introduced the revised bill titled “An Act for the Better Governance of India.” With this act, the British government took direct control over India, replacing the Company’s rule with a new administrative framework designed to improve governance.

Government of India Act 1858 Background

The Government of India Act 1858 is deeply rooted in the political, economic, and social unrest that sparked the Revolt of 1857. The East India Company, which had been administering India since the mid-18th century, was heavily criticised for its policies, which were perceived as exploitative and oppressive.

- The Revolt of 1857, also known as the First War of Indian Independence, exposed the weaknesses of the Company’s rule and demonstrated the need for a more direct and centralised form of governance.

- In response to the revolt and the realisation that the Company was incapable of effectively managing the administration, the British government decided to take direct control of Indian territories.

- The British Parliament passed the Government of India Act in 1858, also known as the Act for Better Government of India. This act was a watershed moment, reflecting the British determination to restructure Indian governance and prevent similar widespread uprisings from occurring in the future.

Queen Victoria’s Proclamation of 1858

Queen Victoria’s Proclamation of 1858 marked the transfer of power in India from the British East India Company to the British Crown. The proclamation, issued on November 1, 1858, sought to establish direct governance by the British monarch and ensured the British Crown’s sovereignty over India.

- It promised to respect Indian princes’ rights, avoid interference in religious matters, and abolish the Doctrine of Lapse.

- The proclamation aimed to stabilise British rule following the 1857 rebellion by ensuring the protection of Indian states and granting Indian subjects equal rights under British law.

Government of India Act 1858 Provisions

The Government of India Act of 1858 was enacted following the Revolt of 1857. The Act for the Good Government of India abolished the East India Company and introduced several key provisions to reorganise the governance of India:

- Transfer of Power: The Government of India Act of 1858 transferred the East India Company’s powers, territories, and revenues to the British Crown, effectively ending the Company’s rule in India.

- The act vested the British Crown with direct control over the Indian territories, with the monarch represented by the Governor-General of India.

- The Governor-General was also given the title of Viceroy, reflecting the Crown’s direct authority.

- Establishment of Secretary of State for India: The Government of India Act of 1858 established the position of Secretary of State for India, a member of the British Cabinet in charge of Indian affairs.

- A 15-member Council of India was also formed to assist the Secretary of State. The initiative and final decision were to be with the Secretary of State, and the council was to be advisory.

- He was also the point of contact between the British government in Britain and the Indian administration. He also had the authority to send secret communications to India without consulting his council.

- Governor-General and Viceroy: The Governor-General of India was appointed Viceroy, acting as the Crown’s representative in India. Lord Canning became the first Viceroy under the new system.

- Abolishment of Dual Government: The Government of India Act of 1858 abolished the Board of Control and the Court of Directors, effectively ending the double government system.

- Reorganisation of Indian Civil Services: The Government of India Act 1858 established the Indian Civil Services (ICS), which were open to Indians via competitive examinations.

- Expansion of Legislative Councils: The Government of India Act 1858 expanded the powers of legislative councils. It enabled the establishment of legislative councils at the provincial level, where laws could be enacted, amended, or repealed. These councils consisted of both official and non-official members.

- However, Indian representation was limited and did not accurately reflect the Indian population. The majority of the members were British officials.

- Military Reforms: The Act of 1858 brought the Indian Army under the direct control of the British Crown, with the Commander-in-Chief of India being subordinate to the Governor-General.

- Princely States: It was decided that the remaining Indian princes and chiefs (over 560 in number) would retain their independence as long as they accepted British rule.

Government of India Act 1858 Significance

The Government of India Act 1858 was crucial in reshaping India’s governance and transitioning power from the East India Company to the British Crown. The Act was significant for several reasons:

- Direct Rule of British: The Government of India Act of 1858 centralised India’s administration, placing it directly under the control of the British Government. This marked the start of the British Raj, a period of direct colonial rule that continued until 1947.

- End of Company Rule: The Government of India Act 1858 ended the rule of the East India Company, which had served as the primary agent of British imperialism in India for over a century. This shift marked a significant reorganisation of colonial governance.

- This Act also abolished the dual governance system envisioned by Pitt’s India Act of 1784, declaring India a direct British colony.

- Foundation for Future Reforms: The Government of India Act of 1858 paved the way for future legislative reforms in India, including the subsequent Government of India Act of 1935, which increased Indian representation in government.

Government of India Act 1858 Limitations

While the Government of India Act 1858 introduced significant changes in India’s governance, it had notable limitations that hindered meaningful Indian participation and maintained the colonial power structure.

- Lack of Indian Representation: The Government of India Act 1858 did not provide for any meaningful representation of Indians in the new administrative structures. The governance of India remained firmly in British hands, with little input from Indian leaders.

- Centralisation of Power: The Government of India Act of 1858 centralised power within the British government, reducing the autonomy of Indian provinces and restricting their capacity for self-governance.

- Continuation of Colonial Exploitation: While the Government of India Act of 1858 reorganised the administration, it did not address the root causes of the Revolt of 1857, which were economic exploitation and social inequality. The British Crown maintained policies favouring imperial interests over the welfare of the Indian people.

- Failed Reforms: The Government of India Act of 1858 failed to create a comprehensive constitutional framework for India, resulting in ambiguous legal and administrative guidelines.

- For example, the act instituted some reforms in the Indian Civil Services, but it did not significantly increase opportunities for Indians to advance to higher administrative positions.

The Government of India Act of 1858 marked a pivotal shift to direct British rule in India, centralizing power under the Crown and introducing major administrative reforms. However, it failed to address critical issues like Indian representation and ongoing colonial exploitation. Despite its limitations, the act established the British Raj, laying the groundwork for future reforms and, ultimately, Indian independence.

Emergence of Indian National Congress

The Indian National Congress was founded in 1885 under the leadership of A.O. Hume. Originally known as the Indian Nation Union, the establishment of the Indian National Congress in 1885 was not a coincidence. It emerged as a result of a political awakening process that began in the 1860s and 1870s, culminating in the late 1870s and early 1880s.

This process experienced a significant turning point in 1885 when modern political thinkers, who saw themselves as champions of the nation’s interests rather than specific interest groups, witnessed the fruition of their efforts. They formed a nationalist organization that operated on a pan-Indian scale, serving as a platform, coordinator, focal point, and representation of the emerging national politics.

History

- The Indian National Congress was founded by 72 delegates on December 28, 1885, at Gokuldas Tejpal Sanskrit College in Mumbai (then Bombay). It was created by former Indian Civil Services Officer Allan Octavian Hume. The Congress was established to foster a climate that would allow for polite dialogue between Indians and the British.

- Only educated Indians were invited to the Congress. Through the Congress, the British could gain support for their rule in India. This was made feasible because educated Indians were more receptive to modernization concepts and could therefore influence other Indians. The General Secretary of the Congress was Allan Octavian Hume, and the President of the Congress was Womesh Chunder Banerjee.

Foundation

- The foundation for the establishment of a pan-Indian organization began to take shape in the late 1870s and early 1880s. A.O. Hume, a retired English civil official, played a crucial role in crystallizing this idea by seeking the assistance of prominent intellectuals of that era.

- To hold the inaugural session, Hume obtained permission from Lord Dufferin, who was the viceroy of India at the time. However, due to a cholera outbreak in Poona, the original location, the session was moved to Bombay. In 1883, Hume expressed his desire to create an organization that would represent educated Indians and advocate for increased participation in government. He conveyed this intention through an open letter addressed to graduates of Calcutta University.

- An important milestone in the history of the Indian National Congress was the participation of Kadambini Ganguly, the first woman to graduate from Calcutta University. In 1890, she delivered a speech at the Congress, highlighting the commitment of the freedom movement to ensuring equal rights and opportunities for Indian women in public life.

Feature

- The Indian National Congress (INC) was the first nationwide political movement in India, initially focused on promoting Indian participation in governmental affairs. However, its objective later evolved to strive for complete independence from British rule. After India gained independence, the INC transformed into a prominent political force within the country. In its early stages, the INC followed a moderate approach, employing constitutional means and discourse as its primary tactics.

- During this period, the party’s demands were limited to advocating for increased representation of Indians in the armed services and government, without explicitly discussing independence. Over time, the party’s demands and strategies became more radical.

- By 1905, clear divisions had emerged within the party. The more recent faction, known as the extremists, employed more radical tactics, while the long-standing moderates pursued a more restrained approach. Alongside the Indian National Congress, provincial conferences, associations, newspapers, and literature also played significant roles in the nationalist movement.

Objective

- The primary objective of the Indian National Congress (INC) was to promote and enhance Indian participation in governmental affairs. As the country’s first large-scale political movement, the INC aimed to establish friendly connections among nationalist political activists from different regions of the nation. It sought to foster a sense of national unity that transcended barriers of caste, religion, and province.

- The INC had multiple goals, including the compilation and submission of a list of general demands to the government. Additionally, the organization aimed to organize and shape public opinion across the country. It actively worked towards creating and promoting an anti-colonial nationalist ideology while upholding a strong sense of national unity among all citizens, irrespective of their religious, caste, or provincial identities.

Role of A. O Hume

- A.O. Hume played a significant role in the establishment and early years of the Indian National Congress (INC). While the idea for an all-India congress was discussed by a small group before Hume’s involvement, it is believed that his Indian Union, which he founded after leaving the Civil Service, contributed to the formation of the Congress.

- Hume, the son of British radical activist Joseph Hume, inherited his father’s political beliefs and initially had an interest in European revolutionary groups. He began his career with the East India Company in 1849 and was stationed in the Northwestern Provinces of India. During his time there, he developed an interest in initiatives aimed at promoting education, addressing social issues, and advancing agriculture. Hume even launched a newspaper in 1861 to raise awareness about political and social matters among the residents of Etawah.

- Hume’s pro-Indian stance and his efforts to improve Indian welfare were not appreciated by other British commanders. In 1870, he became Secretary to the Government of India, but his opinions led Viceroy Northbrook to threaten his dismissal. Hume’s strained relationship with Lord Lytton further led to his demotion in 1879, and he eventually left the civil service in 1882.

- After settling in Shimla, Hume developed a strong interest in Indian politics. He felt a closer connection to the Bombay and Poona factions of Indian leaders rather than those in Calcutta, such as Surendranath Banerjee and Narendra Nath Sen. Hume also acquainted himself with Viceroy Lord Ripon and became interested in his plan for local self-government.

- Overall, A.O. Hume’s background, experiences, and passion for Indian politics contributed significantly to his role as one of the key figures behind the formation of the Indian National Congress.

Foundation Theories

- There are several theories surrounding the foundation of the Indian National Congress (INC). Here are three prominent theories:

Safety Valve Theory (Lala Lajpat Rai)

- According to this theory, proposed by Lala Lajpat Rai, it is speculated that A.O. Hume, a retired English civil officer, established the INC as a means to address the growing discontent and unrest against British rule. It is suggested that Viceroy Dufferin may have suggested the idea of an annual gathering of intelligent Indians for political discussions. However, there is no concrete evidence to support the claim that Dufferin influenced the formation of the INC or that it was intended as a “safety valve” to vent out frustrations.

Conspiracy Theory (R.P. Dutt)

- The conspiracy theory, put forth by Marxist historian R.P. Dutt, suggests that the INC was a scheme orchestrated by bourgeois leaders to suppress a potential uprising of the Indian people. According to this theory, the INC was formed as a deliberate strategy to control and manipulate the nationalist movement.

Lightning Conductor Theory (G.K. Gokhale)

- G.K. Gokhale proposed the Lightning Conductor Theory, which posits that politically aware Indians wanted to establish a national organization to voice their political and economic aspirations. However, if they had attempted to create such an organization independently, the authorities would have strongly opposed it and likely suppressed its existence. Therefore, the early leaders of the INC utilized A.O. Hume as a “lightning conductor” or catalyst to unite patriotic forces and provide a platform for their political aspirations, albeit under the guise of a “safety valve.”

- It is important to note that these theories offer different perspectives on the motives and circumstances surrounding the establishment of the Indian National Congress. The accuracy and validity of each theory may vary, and further research and analysis are necessary to ascertain the true factors that contributed to the foundation of the INC.

Moderate Group

The period between 1885 and 1905 is commonly referred to as the Moderate Phase, led by moderate leaders. During this time, influential figures like Dadabhai Naoroji, Pherozshah Mehta, D.E. Wacha, W.C. Bonnerjea, and S.N. Banerjee held prominent positions in Congress and shaped its policies. These leaders were strong advocates of “liberalism” and pursued moderate political approaches. They were known as Moderates to differentiate them from the extremists who emerged in the early twentieth century. The emergence of Indian nationalism in the late 19th century was influenced by various factors such as the spread of Western education, socio-religious reforms, British policies, and other contributing elements.

Features

- During the Moderate Phase, which took place between 1885 and 1905, the Early Nationalists, commonly known as the Moderates, emerged as a significant group of political leaders in India, marking the beginning of the organized national movement. Two prominent moderate leaders were Pherozeshah Mehta and Dadabhai Naoroji.

- The Moderates consisted primarily of educated middle-class professionals, including lawyers, teachers, and government officials, many of whom had received their education in England. Their political activities followed a constitutional approach, focusing on lawful agitation and demonstrating a gradual and orderly political progression.

- The Moderates held the belief that the British authorities genuinely intended to be fair to the Indians but lacked awareness of the actual conditions in India. They believed that by shaping public opinion within the country and presenting public demands through resolutions, petitions, meetings, and other means, the authorities would gradually meet these demands.

- To achieve their objectives, the Moderates employed a two-pronged strategy. Firstly, they aimed to create strong public opinion to awaken consciousness and foster national spirit among the people. They also worked towards educating and uniting individuals on common political issues. Secondly, they sought to persuade the British government and public opinion to implement reforms in India in line with the nationalist agenda.

- In 1899, a British committee of the Indian National Congress was established in London, serving as its representative body. Dadabhai Naoroji played a significant role in advocating for India’s cause on international platforms, dedicating a considerable portion of his life and resources to this endeavour.

- Although there were plans to hold a session of the Indian National Congress in London in 1892, the proposal was postponed due to the British elections in 1891 and was subsequently not revived.

Objectives

- The objectives of the Moderate Phase during the late 19th and early 20th century in India were as follows:

- Establish a democratic, nationalist movement: The Moderates aimed to create a movement that would advocate for the rights and aspirations of the Indian people within a democratic framework.

- Politicize and politically educate people: The Moderates sought to raise political awareness among the Indian population, particularly the educated middle class, and educate them about their rights and responsibilities as citizens.

- Establish a movement’s headquarters: The Moderates aimed to establish a central headquarters or organization that would serve as a platform for coordinating and directing nationalist activities throughout the country.

- Promote friendly relations among nationalist political workers: The Moderates emphasized the importance of fostering friendly relationships and cooperation among nationalist political workers from different regions of India, with the goal of creating a unified front against colonial rule.

- Create and spread an anti-colonial nationalist ideology: The Moderates aimed to develop and propagate an ideology that emphasized the need to oppose and challenge British colonial rule in India.

- Formulate and present popular demands to the government: The Moderates believed in formulating popular demands related to economic and political reforms, which would serve as a rallying point to unite the Indian people behind a common agenda. These demands would be presented to the government for consideration.

- Develop and consolidate a sense of national unity: The Moderates worked towards fostering a sense of national unity among people of all religions, castes, and provinces in India. They aimed to transcend divisions and create a shared identity based on the idea of Indian nationhood.

- Promote and cultivate Indian nationhood with care: The Moderates recognized the importance of nurturing and preserving the concept of Indian nationhood, paying attention to its development and ensuring its growth in a thoughtful and deliberate manner.

Important Leaders

- The Moderate Phase of the Indian national movement was characterized by the leadership of several prominent figures. Here are some important leaders from that period:

- Dadabhai Naoroji: Often referred to as the “Grand Old Man of India,” he was the first Indian to be elected to the British House of Commons. Naoroji authored the influential book ‘Poverty and Un-British Rule in India,’ which highlighted the economic drain caused by British policies in India.

- Womesh Chandra Bonnerjee: He served as the first president of the Indian National Congress (INC). Bonnerjee, a lawyer by profession, was also the first Indian to serve as Standing Counsel.

- G. Subramania Aiyer: He founded the newspaper ‘The Hindu,’ through which he criticized British imperialism. Aiyer also established the Tamil newspaper ‘Swadesamitran’ and was a co-founder of the Madras Mahajana Sabha.

- Gopal Krishna Gokhale: Gokhale was an influential leader and political mentor to Mahatma Gandhi. He founded the Servants of India Society, which aimed to promote social and political reforms in the country.

- Surendranath Banerjee: Known as ‘Rashtraguru’ and ‘Indian Burke,’ Banerjee founded the Indian National Association, which later merged with the INC. He was also associated with the Bengalee newspaper. Banerjee faced racial discrimination when he was fired from the Indian Civil Service.

- Other notable moderate leaders include Rash Behari Ghosh, R.C. Dutt, M.G. Ranade, Pherozeshah Mehta, P.R. Naidu, Madan Mohan Malaviya, P. Ananda Charlu, and William Wedderburn. These leaders played significant roles in advocating for India’s rights and pushing for political and social reforms during the Moderate Phase.

The method used by the Moderates

- The Moderates employed several methods to advance their objectives during the Moderate Phase of the Indian national movement. Here are some of the key approaches they used:

- Reform Demands and Criticism: The Moderates articulated reform demands and openly criticized government policies. They highlighted the need for social, economic, and political reforms in India.

- Emphasis on Patience and Reconciliation: The Moderates believed in peaceful and non-violent methods. They prioritized patience and reconciliation over violent confrontations, seeking to resolve issues through dialogue and negotiation.

- Constitutional and Peaceful Means: The Moderates relied on constitutional and peaceful means to achieve their goals. They adhered to legal frameworks and advocated for reforms within the existing system.

- Education and Political Consciousness: The Moderates placed great emphasis on educating people and raising their political consciousness. They aimed to inform and engage the public on matters of national importance, fostering a sense of political awareness among the masses.

- Formation of Public Opinion: The Moderates organized lectures and discussions in different parts of India and England to shape public opinion. They utilized platforms to generate awareness and garner support for their cause. The publication of the weekly journal ‘India’ aimed at disseminating information among the British people.

- Criticism through Newspapers and Journals: The Moderates utilized various newspapers and journals to criticize government policies and advocate for reforms. Publications like the Bengali newspaper, Bombay Chronicle, Hindustan Times, Induprakash, Rast Goftar, and the weekly journal India were utilized to voice their concerns and perspectives.

- Advocacy for Government Investigation: The Moderates called for government investigations into the problems faced by the people and sought viable solutions to address these issues.

- Organizing Meetings and Discussions: The Moderates regularly held meetings and discussions to address social, economic, and cultural issues. These gatherings took place in various locations, including England, Mumbai, Allahabad, Pune, and Calcutta, among others.

- By employing these methods, the Moderates sought to create awareness, mobilize public support, and influence policy-making in their pursuit of reform and progress for

Contributions of Moderate Nationalists

- Economic Critique of British Imperialism

- The Moderate Nationalists made significant contributions to the Indian national movement. Here are some key areas where they made their mark:

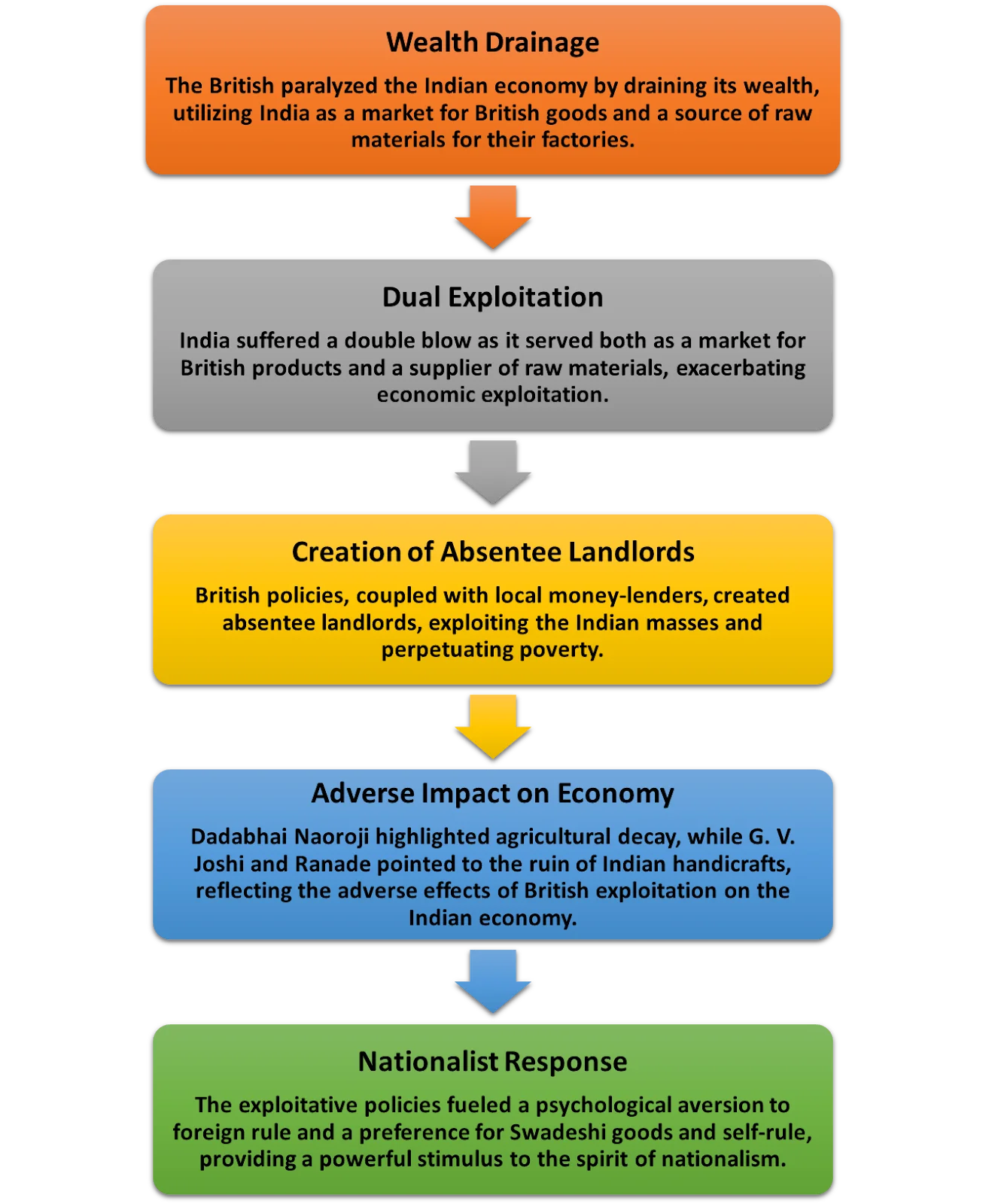

- Economic Critique of British Imperialism: Leaders like Dadabhai Naoroji, R.C. Dutt, Dinshaw Wacha, and others critically examined the political economy of British rule in India. They put forth the “drain theory,” which explained the British exploitation of India’s resources and advocated against the conversion of India’s self-sufficient economy into a colonial one. They created public opinion that British rule was the primary cause of India’s poverty and economic backwardness. They called for an end to economic dependence on Britain, the development of an independent Indian economy, and the involvement of Indian capital and enterprise.

- Demands for Economic Reforms: The Moderate Nationalists demanded various economic reforms to alleviate the deprivation in India. They called for a reduction in inland revenue, the abolition of the salt tax, better working conditions for plantation labourers, and a decrease in military spending, among other measures. Their economic demands aimed to address the exploitative practices and policies of British imperialism in India.

- Advocacy for Constitutional Reforms: Despite limited official power, the Moderate Nationalists actively participated in India’s legislative councils, which were established by the Indian Councils Act (1861). They used these platforms to push for constitutional reforms and to advance the cause of the national movement. While the councils were initially designed as impotent bodies, the work done by the nationalists within them helped in the growth of the national movement.

- Council Expansion and Reform: From 1885 to 1892, the Moderate Nationalists focused on demands for council expansion and reform. They called for greater participation of Indians in the councils and sought more powers for the councils, particularly in terms of control over finances. These demands aimed to increase Indian representation and influence in the decision-making processes of the colonial administration.

- By highlighting the economic exploitation under British rule, advocating for economic reforms, and pushing for constitutional changes, the Moderate Nationalists played a crucial role in shaping public opinion, mobilizing support, and laying the foundation for the broader Indian national movement.

Campaign for General Administrative Reform

- The Moderate Nationalists campaigned for general administrative reform in India, advocating for various changes and improvements. Here are the key grounds on which they campaigned:

- Indianisation of Government Service: The Moderates argued for the inclusion of Indians in government services. They highlighted the economic benefits of employing Indians, as British civil servants received high salaries and remitted a significant portion of their earnings out of India, leading to an economic drain on national resources. They also emphasized the political and moral aspects, arguing that excluding Indians from positions of power was discriminatory and unjust.

- Separation of Judicial and Executive Powers: The Moderates criticized the existing system where the judicial and executive powers were not clearly separated. They advocated for the separation of these powers to ensure a more efficient and impartial administration of justice.

- Criticism of Bureaucracy and Judicial System: The Moderates voiced concerns about the oppressive and tyrannical nature of the bureaucracy. They highlighted the bureaucratic inefficiencies and the time-consuming judicial system, calling for reforms to make these systems more responsive, transparent, and accessible.

- Opposition to Aggressive Foreign Policy: The Moderates criticized the aggressive foreign policy of the British government, which resulted in actions such as the annexation of Burma, the invasion of Afghanistan, and the suppression of tribals in the North West. They argued for a more restrained and just approach to dealing with foreign affairs.

- Increased Spending on Welfare and Development: The Moderates advocated for increased government spending on welfare measures such as health and sanitation, education (particularly elementary and technical education), irrigation works, agricultural improvements, and the establishment of agricultural banks for cultivators. They emphasized the need to prioritize social and economic development to improve the conditions of the Indian population.

- Protection of Indian Laborers in British Colonies: The Moderates raised concerns about the mistreatment and racial discrimination faced by Indian labourers in other British colonies. They called for better treatment and protection of the rights of Indian labourers, highlighting the need for fair and just treatment regardless of their location.

- Through their campaign for general administrative reform, the Moderate Nationalists aimed to address systemic issues, improve governance, and protect the interests and well-being of the Indian population.

Protection of Civil Rights

- The Moderate Nationalists actively advocated for the protection of civil rights in their fight for freedom and independence. They recognized the importance of fundamental rights such as freedom of expression, thought, association, and the press. Here are some key points related to their efforts:

- Spread of Democratic Ideas: The Moderate Nationalists embarked on a continuous campaign to promote modern democratic ideals among the Indian population. They aimed to raise awareness and consciousness about civil rights and the principles of democracy.

- Integration of Civil Rights in the Freedom Struggle: As the national movement progressed, the defence of civil rights became an integral part of the struggle for freedom. The Moderate Nationalists understood that the preservation of civil liberties was crucial in challenging colonial oppression and establishing a just and democratic society.

- Outrage over Arrests and Deportation: The arrest of prominent leaders like Bal Gangadhar Tilak and several journalists in 1897, as well as the arrest and deportation of the Natu brothers without a trial, sparked widespread public outrage. These incidents highlighted the violation of civil rights by the colonial authorities and further fueled the demand for their protection.

- The Moderate Nationalists fought to safeguard civil rights as they recognized their significance in ensuring individual freedoms, promoting democratic values, and challenging oppressive colonial policies.

Achievements of the Moderates

- The Moderate Nationalists made significant achievements in their pursuit of constitutional reforms and political representation. Here are the key accomplishments of the Moderates:

- Indian Councils Act of 1892: The Moderates’ demands for constitutional reform were partially met through the Indian Councils Act of 1892. This act increased the number of members in the Imperial Legislative Councils and Provincial Legislative Councils, allowing for greater Indian representation.

- Expansion of Legislative Councils: The act granted additional responsibilities to the Legislative Councils, such as the ability to engage in budget debates and question the executive. This expansion of their role gave Indian representatives a platform to voice their concerns and participate in the decision-making process.

- Implementation of Indirect Elections: The Indian Councils Act introduced indirect elections (nominations) in both the central and provincial legislative councils. While not fully elected, these nominations allowed for some Indian representation in the councils.

- Demand for Greater Representation and Budget Control: The Moderates, during Congress sessions, criticized the limited scope of the reforms. They demanded a majority of elected Indians in the councils and sought control over the budget. They argued that elected representatives should have the ability to vote on and amend the budget, emphasizing the principle of “No taxation without representation.”

- The achievements of the Moderates in securing constitutional reforms and expanding representation laid the foundation for further advancements in the Indian national movement. While they faced limitations and continued to advocate for more substantial changes, their efforts marked an important step forward in the struggle for political rights and self-governance.

Limitations of the Moderates

- The Moderate Nationalists had certain limitations in their approach and goals within the national movement. Here are some key limitations:

- Limited Mass Involvement: The Moderate Nationalists were predominantly composed of educated elites, such as lawyers, teachers, and government officials. They did not actively seek or prioritize the involvement of the masses in their movement. Unlike leaders like Mahatma Gandhi, who emphasized mass participation and mobilization, the Moderates relied more on intellectual and bureaucratic approaches.

- Distanced from the Masses: The Moderates’ attachment to Western political thought and their emphasis on constitutional methods sometimes created a disconnect between them and the broader population. Their intellectual and elite background made it challenging for them to fully connect with and understand the aspirations and struggles of the common people.

- Limited Goal of Autonomy: Unlike more radical and revolutionary factions within the national movement, the Moderates did not aim for complete independence from British rule. They were content with achieving dominion status, which would grant increased autonomy and self-rule while still being within the British Empire. This more moderate stance may have limited their ability to rally broader support for complete independence.

- It is important to note that these limitations should be understood in the context of the specific time and circumstances in which the Moderate Phase operated. While they had their constraints, the Moderates played a significant role in laying the foundation for the subsequent stages of the Indian national movement.

Evaluation of Early Nationalist

- The evaluation of the Early Nationalists, also known as the Moderates, can be seen in the following light:

- Progressive Forces: The Early Nationalists represented the most progressive forces in India during their time. They advocated for constitutional reforms, civil rights, and economic independence from British imperialism. Their ideas and actions were instrumental in shaping the early stages of the national movement.

- National Awakening: The Moderates played a significant role in creating a widespread national awakening among Indians. They emphasized the need for unity and a sense of belonging to one nation, uniting people across regions, religions, and castes in the common struggle against colonial rule.

- Political Education and Modern Ideas: The Moderates actively worked to educate people about politics and popularize modern ideas. They played a crucial role in raising political consciousness and spreading awareness among the masses.

- Exposing Exploitative Colonial Rule: The Moderates effectively exposed the exploitative nature of colonial rule in India. They highlighted the economic drain and social injustices caused by British policies, undermining the moral foundations of colonialism.

- Realistic and Grounded Approach: The political work of the Moderates was based on hard realities rather than shallow sentiments or religious factors. They focused on practical reforms and gradual progress within the existing system, aiming to govern India in the interests of Indians.

- Foundation for a Mass-Based Movement: The Moderates laid the groundwork for a more vigorous and mass-based national movement that would follow in the years ahead. Their efforts provided a foundation for future leaders and organizations to mobilize the masses and broaden the struggle for independence.

- Limitations in Broadening the Base: One of the criticisms of the Moderates is their limited ability to broaden their democratic base and expand the scope of their demands. They primarily represented the educated elite and did not actively engage or involve the larger masses in the movement.

- In conclusion, the Early Nationalists, or Moderates, played a crucial role in the Indian national movement. They brought progressive ideas, created national awakenings, exposed colonial exploitation, and laid the groundwork for future mass-based movements. However, their limitations in broadening their base and expanding demands are also acknowledged.

Conclusion

- In conclusion, the Moderate Phase of the Indian national movement, led by the Early Nationalists, made significant contributions to the struggle for independence. They believed in peaceful and constitutional methods, seeking to transform colonial rule into a form of national rule that would be in India’s best interests. However, their approach was limited by their reliance on the educated elite and their hesitation to challenge British rule directly.

- While the Moderates were not able to achieve widespread mass participation and lacked radical political positions, their efforts were instrumental in creating a sense of Indian nationalism and raising awareness about the exploitative nature of the colonial rule. They fought for the interests of the emerging Indian nation and laid the foundation for future nationalists who would adopt more militant and mass-based approaches in the struggle against colonialism.

- The Moderates played a significant role in shaping the early stages of the national movement, and their contributions should be recognized in the broader context of India’s journey towards independence.

INTRODUCTION

In the world of today,local government may be said to be a part of the five-tier system of government.The concept of local government is as old kings and kingdoms. There were many kingdoms with excellent local governmentswith the emergence of sovereign states,local governments at the bottom of administrative hierarchy attained significance.Modern states are huge in size. As a result it created a wide gap between state and the masses.The local governments have provided people at the local level to express their grievances and settle it the local level itself.Inbrief,the sole purpose of local government is to solve local level.The following are the definitions of the local self government: Encyclopedia Britanica: “Local government is one where in fixed territory decisions are taken and implemented”, J.J. Clarke: “Local government is a part of national government which looks after the administrative needs of the people of a particular area” Harris: “Local government is a system of government in which living in a particular locality have a responsibility and raise money for their expenditure”

The Panchayat Raj System in India dates back to times of Ramayana and Mahabharata. Kautilya’s “Arthashatrs”and the Megasthanese “Indica” makes areference to panchayat system in India. Ancient India the Gupta village administration was on the whole organized, both at the Centre and the provinces. Gramika was the head of the village but in addition to him there were other officials known as Dutas or messenger,s imakaras or boundary-makers,herds-men, kartri, Lekhaka(scribes), Dandika (Chastiser). Reference is also made to the Parishad or the village assembly, V.D.Mahajan, History of India (from beginning to 1526AD,Pp 271). The Cholas village administration set up highly efficient system of administration. The development of village autonomy was the most unique feature of the Chola administrative system. The two records of Parantaka I (800AD inscription Manur, Uttiramerur, refers to village kudavolai system) contained resolution passed by the local mahasabha on the constitution Variyam or Executive Committes. Each of the 30 wards of the village was to nominate selectioned persons possessing certain qualifications.

LOCAL GOVERNMENT-A BRITISH CREATION

Although local government existed in India in ancient times, in its present structure and style of functioning, it owes existence to the British rule in India. Neither the system of village self-government that prevailed in earlier times,nor the methord of town government which was then in existencevisualized the type of periodically elected representative government responsible to the electorate that had evolved in the west and was planted in India by the British government. “Local self government in India, in the sense of a representative organization, responsible to a body electors, enjoying wide powers of administration and taxation, and funtionning both as a school of training in responsibility and as a vital link in the chain of organisms that make up the government of the country, is British creation.

REGULATING ACT OF 1773

The earlist efforts in municipal Government in India were made in the Presidency towns of Madras,Calcutta and Bombay. In 1687, an order of the Courtof Directors directed the formation of a Corporation of European and Indian members of the city of Madras. However, the Corporation did not survie.Under the Regulating Act of 1773 the Gorvernor-General nominated the servants of the Company and other British inhabitants, to be the Justice of Peace, to appoints for the cleaning and repairing of the street of Calcutta, Madras and Bombay.

In the year 1817 and 1830,spasmodic attempts were made in Madras and Calcutta to undertake works paid out of the lottery funds and much was done with this money in laying out these towns. In1840, an Act widened and in 1841 an Act was passed for Madras. These Act widened the purpose for which the municipalassessment was to be utilized. The inhabitants of the towns were given control over the assessment and collection of taxes. There was no response from the public. In 1845 an Act was passerine for Bombay. This Act concentrated the administrative powers in the hands of a conservancy Board on which were two European an three Indian Justice,with the senior Magistrate of Police as Chairman. The first Act deals with the conservancy and improvement of the Presidency towns. The second act provided for the better assessment and collection of rats. Special Acts were passed for the appointment of the commissioners in each town. In the CalcuttaAct 1856,special provisions were made for gas lighting and the construction of sewers.In the Bombay Act of 1858,power was given to levydues.

NON-PRESIDENCY TOWNS

Outside the Presidency towns there was practically no attempt at municipal legislation before 1842. An Act was passed in that year in Bengal, but it practically remaned a dead lefter another Act was passed in 1850 which applied to the whole of British India . Under this Act and subsequent provincial Act, large number of municipalities were set up in allprovinces. In most provinces, the commissioners were nominated and from the point of view of self-government,these Acts did not go far enough.

MAYO’S RESOLUTION OF 1870

It was only after 1870 that real progress was made in direction of local-self government. Lord Mayo’s government in their Resolution of 1870 dealing with decentralization of finance, referred to the necessity of talking further steps to bring local interests and supervision to bear on the management of funds devoted to educatin, sanitation, public works, etc. New municipal Acts were passed in the various provinces between 1871 and 1874. The Acts extended the elective priniciple. The results of the policy of 1870 were described in the Resolution of the Local self-government,1882,thus considerable progress haad been made since 1870. A large income from local rates and cesses had been secured, and some provinces the management of the income had been freely entrusted to local bodies.

RIPON’S RESOLUTION OF 1881

The next step was taken during the viceroyality of Lord Ripon who has been rightly called the father of Local Self-government in India. His resolution on Local Self-government is a great landmark in the growth of Local Self-government in the country. After pointing out the beneficial effects on the local finance of the resolution of 1870,the resolution of 1881 stated that the Governor-General of India thought time had come when further steps should be taken todevelop the idea of Lord Mayo’s Government. It was asserted that agreements with the provincial Government regarding finance should not ignore the question of Local Self-revenues to the local bodies.

RESOLUTION OF 1882

In this Resolution of Lord Ripon took special pains to make it clear that the expansion of the system of Local Self-government. Would not bring about a change for the better from the point of view of efficiency in municipal administration.

Lord Ripon’s resolution enunciated the following principles which were henceforth to inform and guide local government in India:

1. Local bodies should have mostly elected non-governmental members and chairman.

2. The state control over local bodies should be indirect rather than direct.

3. These bodies must be endowed with adequate financial resources to carry out their functions.To thi end,certain sources of local revenue should be made available to the local bodies which should also receive suitable grants from the provincial budget.

4. Local government personnel should operate under the administrative control of the local bodies. The government personnel who are deputed to the local government must be treated as employees of the localg government and subject to government its control.

5. The resolution of 1882 should be interpreted by the provincial government according to the local conditions prevalent in provinces.

Another significant stage in the history 0f local government was the publication in 1909 of the report of Royal commission upon Decentralization, set up in 1906. It made the following principal recommendations:

1. The village should be regarded as the basic unit of local self-government institutions and every village should be constituted in urban areas.

2. There should be a subatantial majority of elected members in the local bodies.

3. The municipality should elect its own president,but the district collecter should continue to be the president of the district local board.

4. Municipalities should be given the necessary authority to determine the taxes and to prepare their budgets after keeping a minimum reserve fund.Thegovernment shouldgive grants for public works like water-supply,drainagescheme,etc.

5. The bigger cities should have the services of full-time nominated officer.Local bodies should enjoys full control over their employees subject,of course to certain safe-guards for the security of services.

INDIA ISSUED THE RESOLUTION REAFFIRMING 1918

In 1918 the object of self government is to train the people in the managementof their own local affairs and the political education of this sort must in the main take precedence over consideration of departmental efficiency. It follows from this that local bodies should be as representative as possible of the people whose affairs they are called upon to administer, that their authority in the matter entrusted should be real and not nominal and that they should not be subjected to un-nessarycontrol, should learn mistakes and profiting bt them.

The resolution contained the following:

1. Panchayats should be vevied in the villages.

2. local bodies should contain a large elective msjority.

3. local government should be made broad-based by suitably extending the franchise.

4. The president of the local body should be a member of the public and elected,rather than nominated.

5. Local should be allowed freedom in the preparation of the budget,theimposion of taxes and sanction of works.

THE GOVERNMENT OF INDIA ACT OF 1935

The diarchic system of government at the provincial level was replaced by provincial autonomy. The national movement for independence was also reaching new proportions. With the growing strength of the national movement in India ceased to be a mere experimental station of self-government The central provinces set up on enquiry committee in 1935, the united provinces in 1938, and Bombay in 1939. Although the recommendations of the municipal enquiry committees were unevently carried out in various provinces, there was a definite trend towards democratization of local government by further lowering of the franchise and abolition of system of nominations, and secondly by the separation of deliberative functions from excutive ones.

CENTRAL PROVINCES SHEME OF LOCAL GOVERNMENT

An account of local government of this period should contain a description of the scheme of local government formulated originally in 1937 and implemented, in a modified form, in 1948, the central provinces. The architect of this scheme was D.P. Mishra who was the minister of local self-government at time. This scheme was a bold,even revolutionary attempt at the reconstraction of local government in the provinces. It to do away with one stroke the duality of the administrative system-one district administration and another, local government with its two independent entities of rural government and urban local government.

After independent India the janapada scheme was impliemented in 1948. Despite its shortcoming it had a historical role play in the evolution of local government in the Central Provinces. The local government committee, set up in 1957, by Madya Pradesh, observed in its report submitted in 1958. We have, asresult, people available with experience of work of local bodies to man new bodies. We have also a body of people who are accustomed to pay taxes,organize special development or welfare activities and carry out generally other works of public utility: forinstance, it is through their agency that wells are constructed in each district on public participation basis. In the new setup of the three-tier system that we are now proposing, use could be made with great benefit of the people so experienced particularly at the block level institutions.

CONCLUSION

Provides that village panchayats should be recorganiesed and more powers should be India became independent in 1947. Article 40 of the constitution of India given to them so that they can function successfully as units of self-government. Panchayat Raj were passed in many States with a view to give ms core power to village Panchayats. The panchayat is subjected to a wide-ranging system of direction,control and regulation by the state government.The state government has the power to delimit and alter its jurisdiction, to effect mergemenr, and even to extonguishit. It is control over the panchayat extends to almost every aspect of its work, suchas, appointment of staff, records management,financial administration, election etc,

Indian Councils Act of 1892 was passed with the objective of increasing the size of legislative councils in India thereby increasing the engagement of Indians with respect to the administration in British India. Following the foundation of the Indian National Congress, the Indian Councils Act of 1892 represents a significant milestone in India’s constitutional and political history.

Historical Background

- Following the Great Revolt of 1857, British realised that it needed to ensure the help of its Indian subjects in administering India.

- In addition, as nationalism grew in popularity, Indians became more cognizant of their rights.

- Following the founding of the Indian National Congress, the Indian Councils Act of 1892 represents a significant milestone in India’s constitutional and political history.

- After the Act of 1861, the growth of the Indian Constitution is essentially a story of political discontent and agitation interspersed with Council Reforms.

- The reforms that were reluctantly accepted were always found to be insufficient, resulting in dissatisfaction and a demand for more reforms.

- During the 1885-1889,as a result of the growing nationalism, the Indiana National Congress raised several demands through its sessions.

The following were the main demands:

- An ICS test was to be held simultaneously in England and India.

- Expansion of the Legislative Councils, including the adoption of the election-in-place-of-nomination basis.

- Opposition to Upper Burma’s annexation.

- Military spending should be reduced

- Ability to have previously forbidden financial chats.

Lord Dufferin, the Viceroy at the time, convened a commission to investigate the situation. On the other side, the Secretary of State opposed the idea of a direct election. However, he agreed to indirect electoral representation.

Objective

Increase in the size of various legislative councils in India thereby increasing the engagement of Indians with respect to the administration in British India.

Indian Councils Act of 1892 was passed with the objective of increasing the size of legislative councils in India.

|

Key Provisions

- It raised the number of (non-official) members in the Central and Provincial Legislative Councils while keeping the official majority.

- Bombay – 8

- Madras – 20

- Bengal – 20

- North Western Province -15

- Oudh – 15

- Central Legislative Council minimum – 10, maximum 16

- The Act made it clear that the members appointed to the council were not there as representatives of any Indian body, but as nominees of the Governor-General.

- Members could now debate the budget without voting right. They were also barred from asking follow-up questions.

- The elected members were permitted to discuss official and internal matters.

- The Governor General in Council was given the authority to set rules for member nomination, subject to the approval of the Secretary of State for India.

- To elect members of the councils, an indirect election system was implemented.

- Members of provincial councils could be recommended by universities, district boards, municipalities, zamindars, and chambers of commerce.

- Provincial legislative councils were given more powers, including the ability to propose new laws or repeal old ones with the Governor General’s assent.

Significance

- It was the first step toward a representative system of government in contemporary India.

- The number of Indians increased, which was a good thing.

- Despite the fact that Indians did not have the power to veto the majority, their opinions were heard.

- The principle of election, which was accepted in 1892, allowed non-officials to have a free and open discussion on the government’s financial strategy. As a result, the administration had an opportunity to clear up misconceptions and respond to criticism.

- The statute gave members of the council the authority to issue interpellations on subjects of public concern.

Limitations

- Despite being the first step toward a representative government in modern India, this act provided no benefits to the common man.

- This act created the stage for the development of numerous revolutionary forces in India because the British only made a minor concession.

- Many leaders, including Bal Gangadhar Tilak, faulted Congress’s moderate strategy of petitions and persuasions for the lack of significant progress and called for a more assertive policy against British rule.

Conclusion

The Indian Councils Act, 1892 is a significant milestone in India’s constitutional and political history. The act increased the size of various legislative councils in India thereby increasing the engagement of Indians with respect to the administration in British India. The Indian Councils Act, 1892 was the first step towards the representative government in modern India. The act created the stage for the development of revolutionary forces in India because the British only made a minor concession.

- By the beginning of the twentieth century, a new wave of leaders emerged in the Indian nationalism who were distinct from the earlier Moderate leaders. This group was referred to as Extremists due to their adoption of more radical and assertive methods in their fight against British colonial rule. These Extremist leaders believed that more aggressive tactics were necessary to achieve India’s freedom.

- The Extremist leaders were often younger and more inclined towards direct action and confrontation with the British authorities. They rejected the gradualist approach of the Moderates and instead advocated for more assertive measures to scare away the British from India. Their methods included acts of protest, civil disobedience, and, in some cases, even armed resistance.

- Bhagat Singh, Chandrashekhar Azad, and Rajguru are examples of prominent Extremist leaders who played significant roles in the fight for independence. They became symbols of resistance and sacrificed their lives for the cause.

- The Extremists represented a shift in the tactics and strategies employed in the national movement. While the Moderates sought reforms within the framework of British rule, the Extremists demanded complete independence and were willing to use more forceful means to achieve it.

- It’s important to note that the Extremist phase was a significant development in the trajectory of the Indian national movement. It reflected the growing frustration and impatience among a section of leaders who believed that more radical measures were necessary to challenge British colonialism.

Extremists and the Partition of Bengal

- The partition of Bengal in 1905 by the British government was a significant event that triggered the rise of the Extremist or Radical factions within the Indian National Congress. The decision to partition Bengal was met with widespread opposition and protests from the Indian population, particularly in Bengal. The Extremists emerged as a response to the failure of the Moderate leaders’ attempts to address this issue through constitutional means.

- Leaders such as Lala Lajpat Rai, Bal Gangadhar Tilak, Bipin Chandra Pal, and Aurobindo Ghosh played pivotal roles in this new phase of the national movement. They were labeled as Radicals or Extremists because they believed that more aggressive and militant methods were necessary to challenge British colonialism and achieve India’s independence.

- The Extremists rejected the gradualist approach of the Moderates and advocated for more assertive and forceful means of resistance. They called for boycotts, strikes, and mass protests as methods of challenging British rule. They believed that achieving freedom required strong and uncompromising actions.

- The rise of the Extremists marked a significant shift in the tactics and ideology of the national movement. They brought a more assertive and confrontational approach to the struggle for independence. The partition of Bengal and the British government’s response to it catalyzed this new phase and the emergence of Extremist leaders.

The rise of Extremism in the Indian national movement can be attributed to several key factors:

- Disappointment with Moderate Achievements: The failure of the Moderate leaders to achieve significant results and bring about substantial reforms despite their efforts led to growing disillusionment among Indians. This disappointment fueled the desire for a more assertive and radical approach.

- Economic and Social Hardships: The severe economic conditions during the famine and plague of 1896-97, exacerbated by British policies, deepened the grievances of the Indian population. The hardships experienced by the people further fueled discontent and a desire for more radical action.

- Influence of Global Events: The influence of global events, such as the Russian Revolution and the overthrow of the Czar in 1917, inspired Indian nationalists with the idea of revolutionary change and the possibility of challenging oppressive regimes.

- Impatience and Frustration: The lack of significant progress and the slow pace of reforms under the Moderate leaders led to a sense of impatience and frustration among Indian nationalists. They felt that more radical measures were needed to achieve their goals and secure Indian independence.

- Partition of Bengal: The partition of Bengal in 1905, orchestrated by Lord Curzon, was a major catalyst for the rise of Extremism. It sparked widespread protests and nationalist sentiments, as it was seen as a deliberate attempt to divide and weaken the Indian population.

- National Pride and Cultural Identity: The growing sense of national pride and the revival of Indian cultural identity played a significant role in motivating Indians to take more extreme measures in their struggle against British rule. They resented British attempts to Westernize and undermine Indian culture.

- Inspiration from International Movements: The national movements in other countries, such as Persia, Egypt, and Turkey, inspired Indian nationalists. The success and resilience of these movements against colonial powers served as a source of motivation and solidarity for the Extremist leaders.

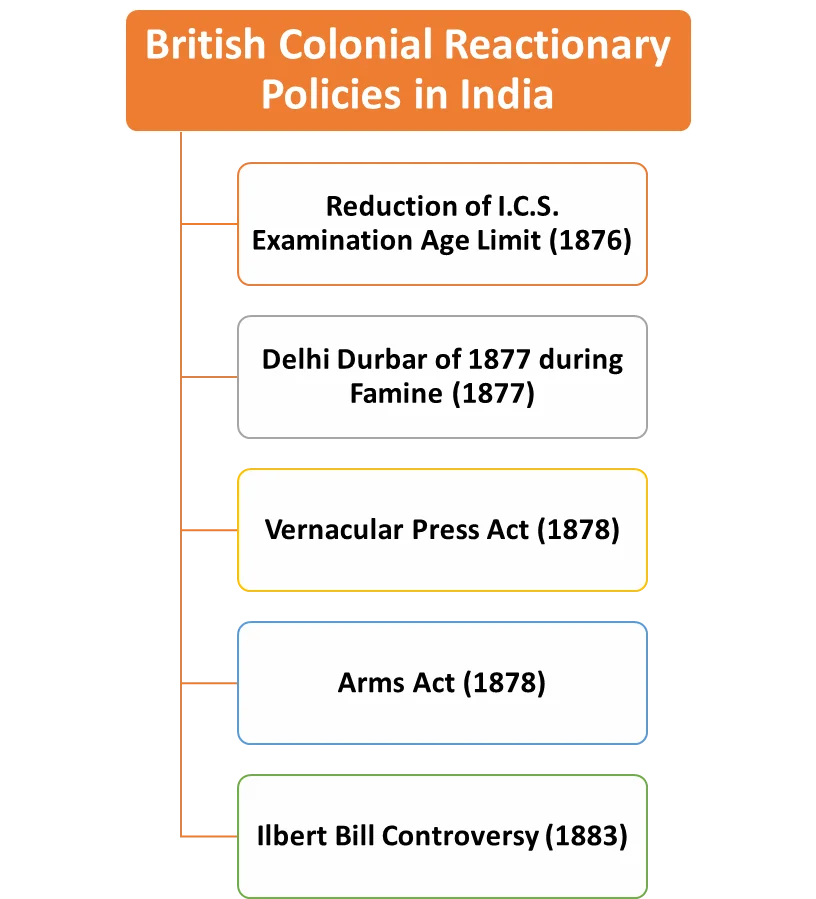

- Reaction to British Arrogance: The arrogance displayed by British officials, particularly during the Delhi Durbar, where the plight of the people suffering from famine was ignored, further angered Indians and contributed to the rise of Extremism.

- These factors collectively contributed to the emergence of the Extremists, who sought to adopt more radical and militant methods in their struggle for India’s independence. They believed in the urgency of the cause and were willing to confront the British authorities more aggressively.

Surat Split

- The Surat Split of 1907 was a significant event that highlighted the ideological differences between the Moderates and the Extremists within the Indian National Congress. The split occurred during the Congress session held in Surat, Gujarat. Here are some key points regarding the Surat Split:

- Leadership Conflict: The main cause of the split was the disagreement over the selection of the Congress president. The Extremists, led by Bal Gangadhar Tilak, wanted him to be the president, while the Moderates, represented by Rash Behari Ghosh, preferred their candidate. The Moderates used procedural rules to shift the venue to Surat, where they hoped to exclude Tilak from the presidency.

- Differences in Approach: The Moderates, who advocated for a gradual and constitutional approach towards attaining self-government within the British Empire, aimed to distance the Congress from more radical resolutions such as swadeshi (boycott of foreign goods), boycott movements, and national education. The Extremists, on the other hand, supported more assertive and militant methods in the struggle for independence.

- Suppression of Voices: During the session, the Moderates prevented Tilak from speaking, which angered the Extremists. This suppression of voices and the refusal to accommodate the demands of the Extremists created further animosity and led to a deadlock.

- Demand for Boycott: In response to the exclusion of Tilak and the refusal to address their demands, the Extremists demanded a boycott of the Surat Session, leading to a significant division within Congress.

- Violence and Disruption: The Surat Session witnessed violent clashes and disruptions between the supporters of the Moderates and the Extremists. The session ultimately ended in chaos and the split of the Congress into two factions.

- The Surat Split marked a significant turning point in the Indian national movement, with the division between the Moderates and the Extremists becoming more pronounced. While the Moderates aimed for incremental reforms and cooperation with the British, the Extremists sought a more confrontational and radical approach. Despite the violence and division, the split highlighted the growing frustration and divergence of strategies within Congress as different leaders pursued their visions of achieving independence.

Methods of Extremist Leaders

- The Extremist leaders adopted more assertive and militant methods in their struggle for independence. Here are some key methods employed by the Extremist leaders:

- Demand for Swaraj: The Extremists aimed for the attainment of “Swaraj,” which meant either complete autonomy and freedom from British rule or a total Indian control over the administration, without necessarily breaking away from the British Empire.

- Inclusion of a Larger Section of People: The Extremists had a broader reach and involved a larger section of people in the movement, including the lower middle class. They aimed to mobilize and unite the masses in their fight against British rule.

- Non-Constitutional Methods: Unlike the Moderates, who focused on constitutional means, the Extremists went beyond the traditional methods of protest and made use of strikes, boycotts, burning of foreign goods, and other forms of non-cooperation to challenge British authority.

- Confrontation: Extremist leaders believed in confrontation rather than persuasion. They openly challenged and opposed British imperialistic policies in India and did not shy away from direct confrontations with the colonial administration.

- Promotion of the Swadeshi Movement: The Extremists actively supported and promoted the Swadeshi movement, which encouraged the use of indigenous goods and the establishment of Indian banks, mills, factories, etc. This movement aimed to reduce dependence on foreign goods and boost Indian industries.

- Pride in Indian Culture: Extremists took pride in Indian culture and history. They drew inspiration and courage from ancient Indian scriptures and heroes. They aimed to revive and promote Indian traditions and values, opposing the Westernization of Indian society.

- Sacrifice and Patriotism: Extremist leaders were willing to sacrifice anything, including their lives, for the cause of the motherland. They instilled a sense of self-respect and patriotism among the masses, citing the bravery and sacrifices of past Indian heroes.

- Opposition to British Rule: Unlike the Moderates, who sometimes had equivocal positions, the Extremists clearly opposed British rule and showed no loyalty to the British Crown. They viewed the British as the primary obstacle to Indian self-rule.

- The Extremist leaders played a crucial role in mobilizing the masses, promoting self-reliance, and challenging British authority in India. Their methods aimed at achieving a more radical transformation of Indian society and governance, reflecting the growing discontent and desire for complete independence from British rule.

Government Reaction to Extremist

- The British government reacted strongly to the activities and influence of the Extremist leaders. They implemented several laws and took aggressive measures to suppress the Extremist movement. Here are some notable actions taken by the government:

- Laws to Restrict Activities: The British government passed laws such as the Seditious Meetings Act of 1907, the Indian Newspapers (Incitement to Offences) Act of 1908, the Criminal Law Amendment Act of 1908, and the Indian Press Act of 1910. These laws aimed to restrict the activities of the Extremists, curb freedom of speech and assembly and control the press.

- Imprisonment of Tilak: Bal Gangadhar Tilak, one of the prominent Extremist leaders, was sentenced to imprisonment. He was sent to Mandalay Prison in Burma (now Myanmar) for his alleged support of the revolutionaries involved in the killing of two British women, even though their original target was a British magistrate.

- Repression and Surveillance: The British government intensified its efforts to suppress the Extremist movement through repression and surveillance. Extremist leaders and their supporters were closely monitored, and any sign of subversive activities was dealt with harshly.

- Bans on Extremist Literature and Publications: The government imposed strict censorship and bans on Extremist literature and publications. They aimed to control the dissemination of ideas that challenged British rule or promoted anti-colonial sentiments.

- Use of Police and Security Forces: The British government employed police and security forces to crack down on Extremist activities. Raids, arrests, and crackdowns on public meetings and gatherings were common methods used to suppress the movement.

- These measures reflected the British government’s determination to counter the Extremist movement and maintain its control over India. They sought to restrict the influence and activities of the Extremist leaders and maintain law and order in the face of growing resistance to British rule.

List of Extremist Leaders

- Lala Lajpat Rai: Also known as Punjab Kesari (Lion of Punjab), Lala Lajpat Rai was a prominent Extremist leader from Punjab. He played a crucial role in mobilizing the masses and advocating for Swaraj (self-rule) through radical means.

- Bal Gangadhar Tilak: Bal Gangadhar Tilak was an influential Extremist leader from Bombay (now Mumbai). He strongly advocated for Swaraj and played a significant role in organizing mass movements such as the Ganapati and Shivaji festivals to mobilize people against British rule.

- Bipin Chandra Pal: Bipin Chandra Pal was an Extremist leader from Bengal. He was part of the Lal-Bal-Pal trio along with Lala Lajpat Rai and Bal Gangadhar Tilak. He vehemently criticized British policies and advocated for complete independence from colonial rule.

- Aurobindo Ghosh: Aurobindo Ghosh, also known as Sri Aurobindo, was a prominent Extremist leader from Bengal. He was involved in revolutionary activities and played a crucial role in inspiring the youth towards the cause of independence. However, he later turned towards spirituality and became a renowned spiritual philosopher.

- Rajnarayan Bose: Rajnarayan Bose was an Extremist leader and one of the founders of the Indian National Association. He played a significant role in promoting nationalist ideas and organizing public meetings to raise awareness about the need for self-rule.

- A. K. Dutt: Ashwini Dutta was indeed a prominent Indian freedom fighter, philanthropist, educationist, social reformer, and nationalist. He played a significant role in the Indian independence movement and worked towards the betterment of society. His educational achievements and legal background contributed to his activism and leadership in various social and political endeavours.

- V. O. Chidambaram Pillai: V. O. Chidambaram Pillai, also known as V.O.C., was an Extremist leader from Tamil Nadu. He was a lawyer and a prominent figure in the Swadeshi movement. He played a crucial role in promoting indigenous industries and advocating for self-rule.

- These leaders, along with others, played significant roles in the Extremist phase of the Indian independence movement and contributed to the struggle for freedom from British rule.

Impact of Extremist Period

- The Extremist period in the Indian independence movement had a significant impact on society and various aspects of Indian life. Here are some key impacts:

- Cultural Revival: Extremist leaders like Bal Gangadhar Tilak emphasized the revival of Indian culture and heritage. Celebrations of festivals like Ganpati Puja and the glorification of historical figures like Shivaji helped instil a sense of pride in Indian traditions and values, countering the influence of Westernization.

- Popularization of Nationalist Slogans: Tilak’s powerful slogan “Swaraj is my birthright and I shall have it” resonated with the masses and became a rallying cry for the freedom struggle. It inspired a sense of determination and unity among Indians in their fight against British colonial rule.

- Boycott Movements: The Extremists promoted boycotts of British goods and institutions, including education. This led to a significant shift in the Indian economy as indigenous industries and products gained prominence, providing employment and economic opportunities for Indians. Boycotts also served as a form of protest against British policies and exploitation.

- Education Reforms: Extremists focused on reforming the education system to promote nationalism and self-reliance. They advocated for the establishment of national universities that were free from government control, allowing for the development of an education system aligned with Indian values and aspirations.

- Mobilization of Masses: The Extremist leaders successfully mobilized a larger section of society, including the lower middle class and rural population, into the freedom movement. This broadened the base of the nationalist movement and made it more representative of the aspirations of the masses.

- Overall, the Extremist period brought about significant social and cultural reforms, fostered a sense of national pride and unity, and laid the foundation for a more assertive and militant phase of the Indian independence movement.

Work of the Extremist

- The Extremists were a group of Indian nationalists who emerged in the early 20th century. They were dissatisfied with the moderate approach of the Indian National Congress and advocated for a more militant and aggressive stance against British rule.

- The Extremists believed that India could only achieve independence through a mass movement of the people. They called for boycotts of British goods, strikes, and other forms of civil disobedience. They also revived traditional Indian symbols and festivals in order to generate a sense of national pride and unity.

- Some of the most prominent Extremists included Bal Gangadhar Tilak, Bipin Chandra Pal, and Lala Lajpat Rai. They played a significant role in the Indian independence movement, and their ideas helped to shape the course of the struggle.

Here are some of the specific works of the Extremists:

- Boycott of British goods: The Extremists called for a boycott of British goods to weaken the British economy and pressure them to leave India. They encouraged people to buy Indian-made goods instead of British goods.

- Use of Swadeshi goods: The Extremists also promoted the use of Swadeshi goods or goods that were made in India. They believed that this would help to boost the Indian economy and create jobs.

- Public meetings: The Extremists held public meetings to spread their message and mobilize support for their cause. They spoke at these meetings about the evils of British rule and the need for independence.

- Passive resistance: The Extremists also practiced passive resistance, or refusing to cooperate with the British authorities. This included refusing to pay taxes, boycotting government schools, and refusing to serve in the British army.

- National education: The Extremists also believed that it was important to provide Indians with a national education, one that would instill in them a sense of pride in their country and its culture. They founded schools and colleges that taught Indian history, culture, and languages.

- The work of the Extremists helped to raise awareness of the Indian independence movement and to mobilize support for the cause. They played a significant role in shaping the course of the struggle, and their ideas continue to inspire people today.

Achievements of Extremists

- The achievements of the Extremists during the Indian independence movement were significant and had a lasting impact on the course of the struggle. Some of their key achievements include

- Demand for Swaraj: The Extremists were the first to boldly demand complete self-rule or Swaraj for India. They advocated for the idea that Indians had the inherent right to govern themselves and should strive for independence from British colonial rule.

- Mass Mobilization: The Extremists played a crucial role in mobilizing the masses and involving a wider section of society in the freedom struggle. They recognized the importance of grassroots participation and actively worked towards raising awareness and garnering support among the common people.