Medieval & Modern – 3rd Year

Paper – I (PYQs Soln.)

Unit I

Language/भाषा

Napoleon’s Excessive Ambition:

Napoleon’s Empire was characterised by its heterogeneity:

The French Naval Power Has Several Weaknesses:

During Napoleon’s reign, the French navy was far inferior to that of the United Kingdom. In particular, the defeat of the French fleet in the Battle of the Nile (1798) and in the Battle of Trafalgar (1805) by the British navy demonstrated the strength of the British navy. Both fights were conducted by Admiral Horatio Nelson, who oversaw the British fleet in opposition to the French. Napoleon’s attempt to invade England was thwarted by the British military’s superiority at the time. Furthermore, Napoleon’s Continental System failed as a result of the French navy’s inability to compete with the British.

Disappointment with the Continental System:

As previously stated, Napoleon’s attempt to undermine the British economy through the Continental system proved to be his worst miscalculation. He grossly miscalculated the naval and commercial might of the United Kingdom.

Rather of causing harm to British trade and commerce and causing her economy to collapse, the Continental System had the opposite effect on France. England, backed by a formidable navy, blockedade the European ports and prevented neutral ships from entering the continent. In response to the British embargo, the European nations abandoned the Continental System and continued to trade with the United Kingdom. Napoleon’s attempt to impose the Continental System resulted in the Peninsular War, as well as conflicts against Prussia and Russia, all of which resulted in significant defeats for the French army.

In the Peninsular War, there was a setback:

Even Napoleon himself recognised that it was the Spanish ulcer that ultimately brought him down. Napoleon attempted to establish stronger control over Portugal and Spain in order to enforce the Continental System, which ended in the Peninsular War in 1809 and the French defeat. The fall of the Bourbon King of Spain and the enthronement of Napoleon’s younger brother, Joseph II of France, incited the Spanish people to rise up and fight against the French army of occupation. British backing for the Spanish revolution was demonstrated by the dispatch of Arthur Wellesley, who was tasked with organising and leading the Spanish army of resistance. The French army suffered a crushing defeat during the long-running Peninsular War (1808-1813). Because of Napoleon’s defeat in the Peninsular War, the idea of his invincibility was shattered.

The Russian Campaign Failed Miserably:

A suicidal invasion of Russia by Napoleon with an army of 600,000 men was launched. Aside from the human and financial toll it took, Napoleon’s war against Russia ultimately damaged both his personal and professional reputation. Russia’s scorched-earth approach, combined with a harsh winter, proved to be fatal for the French army’s chances of victory. Hunger, cold, and a Russian invasion contributed to the deaths of a major portion of the French soldiers. Following the collapse of Napoleon’s Grand Army, the Fourth Coalition of powers defeated him in the Battle of Nations (1813) at Leipzig, resulting in the defeat of Napoleon.

Christians are being alienated from their faith:

Another factor contributing to Napoleon’s collapse was the treatment meted out to the Pope by Napoleon. Napoleon’s conquest of the Papal States, followed by the Pope’s imprisonment for refusing to comply with the laws that established the Continental System, alienated Roman Catholics throughout Europe, and particularly in France, during the Napoleonic era. Napoleon suffered a psychological and political setback as a result of his isolation from Catholics.

A coalition of political powers:

After banding together against Revolutionary France, the monarchical European powers maintained their alliance against Napoleon. Napoleon’s ambitious plans for Europe resulted in the formation of a coalition of continental countries against him, which he did not intend. As many as four coalitions against Napoleon were formed by the countries of England, Austria, Prussia, Russia, and later, Sweden. Despite the fact that he had been successful in dismantling the last three alliances either via diplomacy or force, he was unable to prevent them from plotting against him. Napoleon would never be able to defeat England, which was at the heart of the anti-Napoleonic coalition. The British navy and economic resources, as well as the Continental System, played a significant role in allowing England to withstand Napoleon’s onslaught. The British general Arthur Wellesley (Duke of Wellington) played a significant part in the Peninsular War and the Battle of Waterloo, which ultimately resulted in Napoleon’s defeat and eventual defeat.

Notwithstanding his military prowess, Napoleon was a brilliant administrator. His personality was a unique blend of many positive characteristics. He rose to prominence as a result of the French Revolution of 1789. He controlled France from 1799 to 1804 as First Consul, and then from 1804 to 1815 as Emperor of the French Republic. He centralised power and, via a series of reforms, he completely transformed the nation. He was opposed to liberty, but he was in favour of equality. France’s economic development was facilitated by improvements in agriculture, trade, and the tax system. He instituted educational reforms, including the introduction of mandatory military training. His innovative work included the Bank of France and the University of France. He instituted the necessary religious changes, which resulted in religion being brought under the power of the government. He became well-liked, and the people readily accepted him as their Emperor. The code that bears his name is such an essential piece of work that it is still used to guide the nation today. Napoleon was considered to be one of the world’s greatest conquerors. Wellington believed that Napoleon’s presence on the battlefield was worth the expenditure of a force of 40,000 troops. His triumphs enabled France to fend off foreign adversaries. He was victorious in numerous battles, vanquished numerous countries, and founded the mighty empire of France. But, in the end, European countries were victorious in 1815 over Napoleon. His numerous decisions, such as continental strategy, the Russian campaign, the Peninsular war, and others, were the primary reasons for his failure.

INTRODUCTION

Immediately after Napoleon’s fall in 1814 and his “retirement” to Elba, a Congress of European diplomats was summoned to meet at Vienna to give peace to “a tired and timid generation” and to deal with a number of political problems consequent upon the upheavals caused by the Wars of Revolutionary France and those of the Napoleonic period.

All big and small countries of Europe, except Turkey, were invited. Vienna was chosen as the venue of the Congress in view of the leading part played by Austria in the final overthrow of Napoleon. As a tribute to her noble part in the struggle, her Chancellor Count Metternich was selected to preside over its deliberations.

THE PROBLEMS BEFORE THE CONGRESS

- Problem of France. What should be the future government and boundaries of France and what punishment should be meted out to her for causing so much bloodshed during the last 25 years?

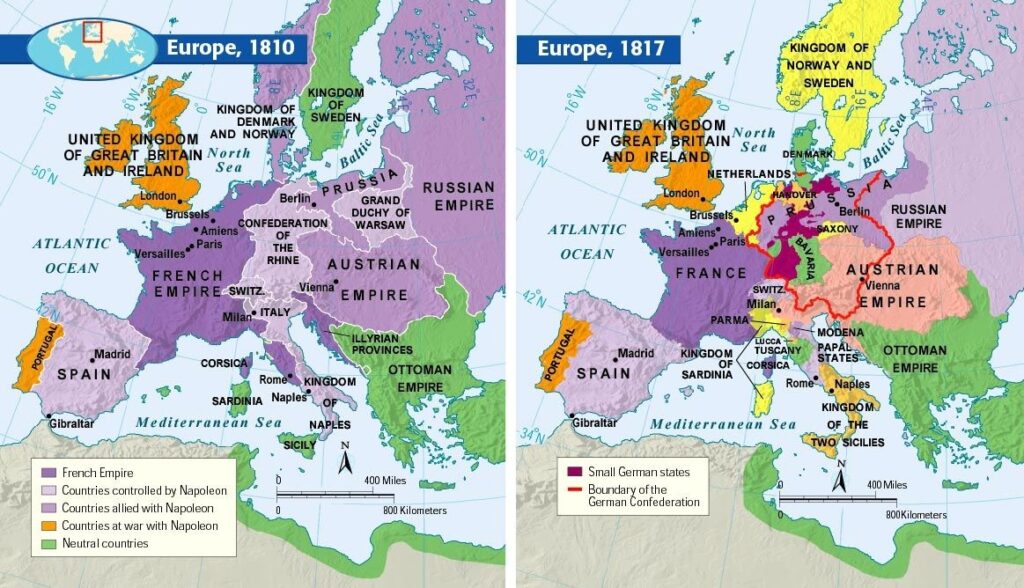

- Reconstruction of the Political Map of Europe. The wars waged by Revolutionary France and Napoleon had completely changed the political map of Europe. Over 200 petty states in Germany had been abolished and the Holy Roman Empire had ceased to exist. New states like the Confederation of the Rhine, the Kingdom of Westphalia, the Grand Duchy of Warsaw and the Kingdom of Italy, etc. had been created by Napoleon. Boundaries of old states like Austria, Prussia and Russia had been altered several times. In short, the up-heaval of the last 25 years had brought about vast political changes in the boundaries of European states. Therefore, the Congress of Vienna had to redraw the political map of Europe and was confronted with the problem of whether to restore or not the old princes who had been dispossessed of their States by France.

THE LEADING PERSONALITIES AT THE CONGRESS

“The Congress was a pageant,” and was associated with much gaiety, feasting and merry-making. The representatives of various countries indulged in an eating and drinking orgy to celebrate their deliverance from the tyranny of Napoleon.

In this galaxy of monarchs and diplomats, the following persons stood out by virtue of their towering personality and they played a significant part in the deliberations of the Congress.

- Foremost among them was Tsar Alexander I, a great idealist and dreamer who was swayed at times by the high ideals of the gospel of Christianity and sometimes was dominated by selfish motives. He was a curious combination of “shrewdness with mysticism, ambition with compassion.” He was young, imaginative and liberal in his outlook, but was “changeable and egoistic and influenced by fear.” On the whole, he stood for a just and fair settlement.

- Emperor Francis I of Austria was obstinate and narrow minded and reactionary in his outlook. “Keep yourselves to what is old, for that is good” was his principle.

- King Frederick William III of Prussia was slow, timid and weak and a great traditionalist. He was terribly fascinated by the Tsar and was extraordinarily reverential to the Emperor.

- Metternich was the most commanding personality from 1815 to 1848. This period in European History is called the “Era of Metternich.” He was the central figure in European diplomacy and was “without a peer in his age or in his style.” He was a shrewd statesman and was a pastmaster in diplomacy, tact and finesse. Like his master, the Emperor, he was also a great reactionary and the most vehement opponent of liberalism. He distrusted all innovations and new ideas and therefore tried his best to maintain the old order.

- Lord Castlereagh, the representative of Great. Britain, was essentially liberal in his outlook, and was an astute statesman, who wielded considerable influence in bringing about compromises when there were deadlocks among the allies.

- Talleyrand, who represented France, was cunning, shrewd and quick to take advantage of the differences among the allies. He had a very keen sense of observation and could exploit the weaknesses of others to his own advantage. He served France ably and saved her from utter humiliation by flattery, chicanery and intrigue. He was so successful in his mission, that, though a representative of the vanquished country, he played a leading role in laying down the policy which formed the basis of the settlement of Vienna. The “Big Four” Austria. Great Britain. Russia and Prussia, had to admit him to their counsels.

THE AIMS OF THE CONGRESS

The deliberations of the Congress had been temporarily suspended by Napoleon’s escape from Elba. After his final defeat at Waterloo, it once again continued with its meetings. Its aims were as follows:

- To Redraw the Political Map of Europe. The wars of the last 23 years had so changed the political boundaries that it was impossible to restore all the European states which existed in 1789. It was not easy to restore the Holy Roman Empire, as the boundaries of some states had been altered several times. The 200 and odd German princes who had been dethroned by Napoleon could not be restored. Notwithstanding this difficulty the Congress still aimed as far as possible to restore the old rulers to their original boundaries.

- To secure permanent Peace in Europe. Revolutionary ideas should be nipped in the bud: never again should France be allowed to spread the principles of Revolution. All germs of liberal opinion must be promptly destroyed. Therefore, the Congress aimed at suppressing all revolutionary movements, wherever they raised their head. For the next ten years or so, the Congress tried to suppress liberalism in Europe by means of the “Concert of Europe” or by means or an alliance of Great Powers.

- To surround France by a Ring of strong States. France should not be allowed to disturb the peace of Europe in future, and hence she should be surrounded by strong and powerful stales on her frontiers. To achieve this end, Prussia, Netherlands and Sardinia were made strong by the addition of large territories so that they might form a bulwark against any further French aggression.

- To distribute the Spoils of War among the Allies. All those countries which had fought against France were to be rewarded at the cost of France and those who had helped her. Therefore territories snatched away from France or her allies were distributed among those who had fought against. France In short, the aim of the Congress was to “divide among the conquerors the spoils of the conquered.”

The Congress mainly worked on the following threefold principles:

1. The Principle of “Legitimacy”. Metternich’s aim was” to restore as far as possible the “rightful” rulers to their old states. This idea was in agreement. with the principle of “legitimacy” which was ably propounded by Talleyrand who cleverly won over Tsar Aleaxnder I to accept this principle and thus saved France for the Bourbons.

In pursuance of this principle, the Bourbons were restored in France and io the thrones of Spain and the Kingdom of Two Sicilies. The House of Orange was restored in Holland, the House of Savoy got Sardinia and Piedmont, and Austria regained Tyrol.

2. The Principle of “Balance of Power” or “Compensation”. But the principle of legitimacy could not be applied to all the States, because during the course of the long wars Great Britain had conquered and annexed a number of colonies belonging to France or to her allies. All of them could not be restored. The British navy had played a very significant role in defeating Napoleon and her services could not be ignored by the Congress. Therefore, she was allowed to appropriate most of the conquered colonies like Mauritius, Tobago, Malta, etc, But those countries besides France which had lost their territories, were compensated in order to maintain the balance of power. Holland got Belgium; Sweden which had lost Finland to Russia was compensated with Norway, and Austria which has renounced her claim to the Austrian Netherlands was rewarded with territories in Italy.

3. To Suppress the Republics. The Congress which was dominated by absolute monarchs and reactionary diplomats was hostile to republics and so the Republics of Genoa and Venice were not restored.

DIFFERENCES AMONG THE BIG AND SMALL POWERS

1. The Future of France. The “Big Four” wanted lo decide everything themselves and ignored the small powers like Spain, Portugal and Sweden. The latter invoked the Treaty of Paris and claimed an equal say in determining the future of France and Europe. Talleyrand took advantage of this cleavage and played the role of a mediator, thus securing for France a voice in the deliberations of the Congress.

2. Differences over Poland and Saxony. Differences also arose between the “Big Four” over the question of the future of Poland and Saxony. Tsar Alexander, on the eve of the battle of Leipzig, had promised Austria and Prussia a share of Poland. But after the battle he changed his mind and now he wanted to appropriate the whole of Poland. In order to win over Prussia, he proposed that Saxony should be given to her.

Metternich was suspicious of the Tsar’s intentions and would not approve of the aggrandizement of Russia and Prussia at the cost of the whole of Poland and Saxony respectively. So supported by Castlereagh he opposed the proposals, And i I seemed that the differences between Russia and Prussia on one side and Great Britain and Austria on the other might lead to the failure of the Congress or even to another war. But Talleyrand’s diplomacy and tact once again stood him in good stead and he eventually suggested a compromise.

Poland was to be repartitioned between Russia, Prussia and Austria, but Russia kept the lion’s share-the so-called “Congress Poland”; Austria retained Galicia; Prussia got Posen and the Corridor. Two-fifths of Saxony was also given to Prussia.

The French Revolution, one of the most pivotal events in world history, was shaped by a complex interplay of causes and forces. Among these, monarchical misrule acted as the spark that ignited the flames of revolution, while the lofty ideals of liberty, equality, and fraternity inspired and sustained the momentum of this profound transformation.

Monarchical Misrule: The Catalyst for Revolution

The mismanagement of the French monarchy, particularly under Louis XVI and his predecessors, was central to the outbreak of the French Revolution in 1789. By the late 18th century, France was burdened by crippling financial problems largely resulting from extravagant royal expenditures and costly wars, including France’s support for the American Revolution. The monarchy’s inability to address the worsening fiscal crisis eroded its legitimacy in the eyes of the people.

The Ancien Régime, the political and social system of pre-revolutionary France, was characterized by gross inequality. Society was divided into three estates: the clergy (First Estate), the nobility (Second Estate), and the commoners (Third Estate). The Third Estate, which represented over 97% of the population, shouldered the heaviest tax burden while being excluded from political decision-making. This glaring social and economic disparity created widespread resentment, particularly as the privileged First and Second Estates enjoyed exemptions from most taxes.

Compounding these systemic issues was the weak leadership of Louis XVI, who lacked the decisiveness and vision to implement necessary reforms. Despite recognizing the gravity of the crisis, he vacillated between attempting to placate reformist demands and defending traditional privileges. His summoning of the Estates-General in 1789 to address the financial crisis backfired, as it provided an unprecedented platform for grievances to coalesce into revolutionary demands. Meanwhile, Queen Marie Antoinette, often portrayed as emblematic of royal excess, became a lightning rod for popular discontent.

These failures were exacerbated by external pressures, such as poor harvests in the late 1780s, which led to widespread famine and skyrocketing bread prices, further alienating the monarchy from the suffering masses. By the eve of the Revolution, the monarchy’s inability to address systemic problems had created an explosive situation, primed for radical change.

The Role of Revolutionary Ideals: Sustaining the Movement

While monarchical misrule ignited the Revolution, it was the ideals of Enlightenment philosophy and the revolutionary vision that sustained its momentum and defined its character. Thinkers like Voltaire, Rousseau, and Montesquieu had laid the intellectual groundwork for revolution by challenging the principles of absolutism and advocating for individual rights, democratic governance, and social equality.

The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, adopted in 1789, encapsulated these lofty ideals. It proclaimed that “men are born and remain free and equal in rights” and asserted principles such as freedom of speech, equality before the law, and the sovereignty of the people. This document became a rallying cry for the revolutionaries and served as a blueprint for subsequent democratic movements worldwide.

The revolution was further fueled by the rise of a new political culture that sought to replace the hierarchical and authoritarian structures of the Ancien Régime with a more egalitarian society. The National Assembly, formed by the Third Estate, emerged as a symbol of popular sovereignty, while revolutionary leaders like Maximilien Robespierre, Georges Danton, and Jean-Paul Marat articulated and amplified the aspirations of the masses.

The ideals of the Revolution found their most dramatic expression during the Reign of Terror (1793-1794), when the revolutionary government, led by the Jacobins, sought to eliminate counter-revolutionary forces and establish a “Republic of Virtue.” While this period was marked by violence and repression, it underscored the extent to which the Revolution was driven by the pursuit of its ideals, even at great cost.

The Global Legacy of the Revolution

The French Revolution was not merely a domestic upheaval; it had profound global ramifications. It inspired revolutionary movements in Europe, Latin America, and beyond, spreading the principles of nationalism, democracy, and human rights. The Napoleonic Code, introduced during the subsequent Napoleonic era, institutionalized many revolutionary ideals and served as a model for legal systems worldwide.

Moreover, the Revolution fundamentally transformed the relationship between the state and its citizens, laying the groundwork for modern concepts of governance. Its emphasis on universal rights and popular sovereignty challenged the legitimacy of monarchies and aristocracies, signaling the dawn of a new political era.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the French Revolution was both a product of monarchical misrule and an embodiment of transformative ideals. While the failures of the French monarchy created the conditions for revolution, it was the powerful vision of liberty, equality, and fraternity that gave the movement its enduring significance. Together, these forces not only reshaped France but also altered the trajectory of global history, making the French Revolution a defining moment in the quest for justice and human dignity.

The Industrial Revolution, which began in England in the mid-18th century, was a transformative period that marked the shift from agrarian economies to industrialized and urbanized societies. It was characterized by significant technological innovations, changes in production methods, and profound social and economic transformations.

Causes of the Industrial Revolution in England

1. Economic Preconditions and Capital Accumulation

England’s economic prosperity in the 18th century provided a strong foundation for industrialization. The country had accumulated significant wealth through its colonial trade network, particularly in the Americas and Asia, which supplied raw materials like cotton and allowed for the export of finished goods. The profits generated from the Atlantic slave trade and plantation economies contributed to the rise of a wealthy merchant class capable of investing in industrial ventures. Additionally, financial institutions, such as banks and joint-stock companies, facilitated capital investment and innovation.

2. Agricultural Revolution

The Agricultural Revolution in England, which preceded the Industrial Revolution, drastically increased food production through innovations such as the seed drill (invented by Jethro Tull) and selective breeding (pioneered by Robert Bakewell). These advancements improved crop yields and livestock quality, reducing the labor required in agriculture. As a result, surplus labor moved to urban centers, providing a workforce for burgeoning industries. The rise in food supply also supported population growth, which created a larger market for manufactured goods.

3. Abundance of Natural Resources

England was uniquely endowed with natural resources essential for industrialization. The country possessed vast reserves of coal and iron ore, critical for powering machinery and building infrastructure. England’s geography, with navigable rivers and ports, facilitated the efficient transportation of raw materials and finished goods. Additionally, the relatively small size of the country allowed for better connectivity and integration of markets.

4. Technological Innovation

England’s Industrial Revolution was driven by a series of technological breakthroughs. Key inventions included the spinning jenny (1764) by James Hargreaves, which revolutionized textile production; the water frame (1769) by Richard Arkwright; and the power loom (1785) by Edmund Cartwright. The most transformative invention was the steam engine, perfected by James Watt in the 1770s, which provided a reliable and versatile source of power for factories, mines, and transportation.

5. Political Stability and Institutional Support

England’s relative political stability following the Glorious Revolution (1688) fostered an environment conducive to economic growth and innovation. The government actively supported industrial development through policies that protected property rights, enforced contracts, and encouraged entrepreneurship. The Patent Law of 1623 incentivized inventors by granting them exclusive rights to their inventions, fostering a culture of innovation.

6. Expanding Markets and Trade Networks

England’s global trade networks, bolstered by its naval supremacy and colonial empire, ensured access to raw materials and markets for manufactured goods. The rise of the domestic market, driven by urbanization and population growth, also contributed to the demand for industrial products. The widespread use of canals and turnpike roads further facilitated trade and communication.

7. Cultural and Scientific Climate

The Enlightenment and the Scientific Revolution in the preceding centuries had created a culture that valued experimentation, empirical observation, and practical application of knowledge. This intellectual climate encouraged inventors and engineers to pursue technological solutions to practical problems, laying the groundwork for industrial innovation.

Impact on Other European Nations

The Industrial Revolution in England had a profound impact on the rest of Europe, setting in motion a process of industrial diffusion and transforming the continent’s economic, social, and political landscapes.

1. Spread of Industrialization

By the early 19th century, industrialization began to spread to other European nations, including Belgium, France, and Germany. Belgium, with its rich deposits of coal and iron, became the first country on the continent to industrialize, developing a strong textile and metallurgical industry. France followed, though at a slower pace due to its turbulent political climate during and after the French Revolution. Germany, despite being politically fragmented, experienced rapid industrial growth after unification in 1871, emerging as a major industrial power by the late 19th century.

2. Economic Transformation

Industrialization fundamentally altered the economies of European nations. Traditional agrarian economies gave way to manufacturing and urbanization. Nations such as Germany and Switzerland became centers of innovation in fields like chemicals, pharmaceuticals, and precision engineering. Railroads, inspired by English innovations, connected markets and accelerated economic integration across the continent.

3. Social Changes

The Industrial Revolution brought significant social changes to European societies. The rise of the factory system created a new working class, while the concentration of wealth in the hands of industrialists and financiers led to the emergence of a powerful bourgeoisie. Urbanization accelerated, as millions migrated from rural areas to industrial cities, transforming the demographic landscape.

However, the rapid pace of industrialization also brought challenges. Poor working conditions, long hours, and low wages in factories led to widespread discontent, giving rise to early labor movements and the eventual emergence of trade unions. In response, governments began to implement social reforms, such as improved working conditions, child labor laws, and public health measures.

4. Political and Ideological Impact

The Industrial Revolution contributed to the rise of ideological movements such as socialism, communism, and liberalism. Thinkers like Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels critiqued the inequalities of industrial capitalism, calling for the overthrow of the bourgeoisie and the establishment of a classless society. The spread of these ideas influenced political movements and revolutions across Europe, particularly in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

5. Technological and Scientific Advancements

European nations embraced the technological and scientific advancements pioneered during the Industrial Revolution, adapting them to their own contexts. For example, Germany became a leader in chemical and electrical industries, with companies like Siemens and BASF spearheading innovation. The application of scientific principles to industry spurred further developments, such as the invention of the internal combustion engine and advancements in steel production.

6. Geopolitical Rivalries and Imperialism

The industrialization of Europe intensified geopolitical rivalries as nations competed for resources, markets, and industrial dominance. Industrial power became a key determinant of military strength, fueling the arms race that culminated in the World Wars. Moreover, industrialized nations expanded their empires, seeking colonies to supply raw materials and serve as markets for manufactured goods.

Conclusion

The Industrial Revolution in England was the product of a unique combination of economic, social, political, and geographical factors. Its innovations and ideas rapidly spread to other European nations, transforming their economies, societies, and political systems. While the Industrial Revolution brought unprecedented economic growth and technological progress, it also introduced new challenges, including social inequality and environmental degradation. Ultimately, it marked the beginning of the modern industrial era, shaping the trajectory of global history and laying the foundation for contemporary industrialized societies.

Napoleon Bonaparte (1769–1821), who rose to prominence during the French Revolution (1787–99), is regarded as one of history’s greatest military leaders. He ruled France from 1804 to 1814 and again in 1815. The Napoleonic Wars (1803–15) and Napoleon’s catastrophic loss at the Battle of Waterloo on June 18, 1815, are what he is best known for today.

Who was Napoleon Bonaparte?

Napoleon Bonaparte, also known as Napoleon I, was born on August 15, 1769, in Ajaccio, Corsica, France. He was the second surviving child of lawyer Carlo Buonaparte and Letizia Ramolino. He was the fourth child, with older brother Joseph and younger siblings Lucien, Elisa, Louis, Pauline, Caroline, and Jérôme. Napoleon underwent Catholic baptism. His father was a lawyer and served as Louis XVI’s representative to Corsica in 1777. Napoleon’s mother played a significant role in his upbringing, instilling strict discipline that helped tame his boisterous behavior. He completed his education on the French mainland and later attended a military academy. Due to being bullied by peers during his youth, Napoleon spent much time alone with books, becoming knowledgeable in geography and history.

The Early Life of Napoleon Bonaparte

- Napoleon attended school on the French mainland and earned his diploma from the military college in 1785.

- Napoleon Bonaparte received a commission in the French Army as a second lieutenant of an artillery detachment.

- Napoleon Bonaparte became associated with the Corsican chapter of the Jacobins, one of many pro-democratic parties in France at the time. At the same time, he was on leave when the French Revolution began in 1789 while he was away from his post.

- The monarchy at the time supported the governor of Corsica, and the Bonaparte family disagreed with them over their pro-democracy views.

- As a result, they left Corsica for mainland France, and Napoleon resumed active military service in 1793.

- Napoleon Bonaparte interacted with Augustine Robespierre, the infamous Maximilien Robespierre’s brother.

- The Reign of Terror, a time of disorder marked by violence against and the execution of people regarded as the enemies of the French Revolution, was ushered in by Maximilien Robespierre.

- But because of his connections to the Robespierre brothers, who lost their position of authority and were executed in July 1794, Napoleon was briefly put under house arrest.

- He was elevated to the rank of major general in 1795 for quelling a rebellion against the revolutionary government supported by the monarchy.

- Napoleon married the French princess Josephine de Beauharnais (1763–1814) in 1796.

- He remarried Marie Louise, Duchess of Parma, in 1814 after divorcing his first spouse. Napoleon II was their only child. Napoleon II later became the king of Rome.

The French Revolution

Napoleon Bonaparte is regarded as a French Revolutionary child. The French Revolution began in 1789 and ended with the ancestors of Napoleon Bonaparte in the late 1790s.

- The French Revolution is a watershed event in the history of modern Europe.

- During the French Revolution, Napoleon Bonaparte climbed quickly through the military ranks.

- The Jacobins were the most well-known and well-liked political organization from the French Revolution, and as a young leader, he soon showed his support for them.

- Napoleon Bonaparte participated in the French Revolutionary Wars, and in 1793 he was given the rank of brigadier general.

Napoleon’s military career

- After completing military training, he joined the French army as the second lieutenant of an artillery detachment in 1785.

- Though a fervent advocate of Corsican nationalism, he finally joined the Jacobins, the pro-French Corsican Republicans, and adopted the goals of the French Revolution, which got underway in 1789.

- By putting down rebellions against the revolutionary government, he advanced through the military ranks during the French Revolution.

- As a result, Napoleon Bonaparte received a promotion to major general.

The Rise of Napoleon Bonaparte

Since 1792, Napoleon has fought in conflicts with other European kingdoms and in the French Revolutionary Wars.

- Treaty of Campo Formio, 1797

- Napoleon led the French army to victory over the larger, better-equipped Austrian soldiers at the Treaty of Campo Formio in 1797.

- France gained new territory due to the Campo Formio Treaty, signed with Austria.

- Battle of Nile, 1798

- He commanded a French mission to take Egypt, a British Protectorate at the time, in the Battle of the Nile (1798).

- The French were completely defeated in the subsequent Battle of the Nile, despite winning the initial Battle of the Pyramids.

- In 1798, he also led a different unsuccessful invasion attempt into Syria, a province of the Ottoman Empire.

- The coup of 18 Brumaire, 1799

- The Directory, a five-person body that had ruled France since the Reign of Terror ended in 1795, staged the coup of 18 Brumaire in 1799.

- Napoleon joined the coup that ousted the director as the political climate deteriorated.

- Battle of Marengo, 1800

- Napoleon’s soldiers expelled the Austrians from Italy after defeating one of France’s longtime adversaries.

- The triumph strengthened Napoleon’s power as the first consul.

- Additionally, the war-weary British consented to peace with the French in the Treaty of Amiens in 1802. (although the peace would only last for a year).

Napoleon I, The Emperor of France

Napoleon Bonaparte became the first consul for life due to the constitutional reform of 1802, which was nothing less than a dictatorship. Then, at a lavish ceremony held in the Notre Dame cathedral later in 1804, Napoleon declared himself the Emperor of France.

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815)

A coalition of European nations and France engaged in a series of conflicts. Napoleon’s 1802 peace treaty was short-lived since by 1803, Britain and France were again at war, and later Russia and Austria joined them.

- Battle of Trafalgar (1805): Napoleon switched his attention to the Austro-Russian forces, which he ultimately beat at the Battle of Austerlitz later that year in one of his finest victories. Britain’s naval success at Trafalgar caused Napoleon to abandon his ambitions to invade England.

- Napoleon Bonaparte devised the Continental System, which blockaded European ports from British Trade, to fight his British adversaries economically. This furthered Napoleon’s reputation as a great general, along with ensuing successes over Russian and Austrian forces.

- The next years saw Napoleon gaining new lands, giving him authority over much of Europe. Along with the Confederation of the Rhine, which was one of Napoleon’s new possessions, the Holy Roman Empire was disbanded, and the rulers of Italy, Naples, Spain, and Sweden were chosen from among his relatives and allies.

What were Napoleon’s Reforms?

- The Napoleonic Code, often known as the French Civil Code, was established by Napoleon on March 21, 1804, and portions of it are still in use today.

- It prohibited birth-based privileges, permitted religious freedom, and mandated that only the most qualified candidates be awarded government employment.

- It includes the commercial code, the criminal code, the military code, and the code of civil procedure.

- Napoleon’s new constitution, which established the first consul, was followed by the Napoleonic Code.

- The post of the first consul was nothing less than a dictatorship.

- Abolished Serfdom and Feudalism: To free the people, Napoleon Bonaparte ended “serfdom and feudalism” in the nation.

- A tenant farmer who lived under serfdom in medieval Europe was subject to his landlord’s whims and confined to an inherited plot of land.

- In European medieval cultures between the 10th to 13th centuries, known as feudalism, a social structure centered on local governmental power and dividing land into units was developed (fiefs).

- Napoleon Bonaparte advocated for universal education and set up a complex system of schools called lycées that is still in use.

The fall of Napoleon Bonaparte

The following factors led to the fall of Napoleon Bonaparte:

- Napoleon’s Continental System, which was largely ineffective and ultimately contributed to his defeat, was an attempt to weaken Great Britain by undermining British commerce.

- The Peninsular War (1807–1814) was a military conflict fought between Spain, Portugal, and the United Kingdom against French invaders and occupiers for control of the Iberian Peninsula.

- Russian invasion: Napoleon sought to deploy proxies to pressure Tsar Alexander I of Russia to halt business with British traders so that the United Kingdom would have to file a peace claim. The campaign’s stated political objective was Poland’s freedom from Russia’s threat.

- The vast French kingdom quickly fell apart after the catastrophic invasion of Russia in 1812.

- Numerous factors, including inadequate supplies, weak leadership, disease, and, not least, the weather, prevented Napoleon from successfully capturing Russia in 1812.

- Napoleon was defeated in 1814, banished to the island of Elba, and defeated again in 1815 in the Battle of Waterloo.

Battle of Waterloo, 1815

- Napoleon escaped to mainland France on February 26, 1815, and was greeted in Paris by jubilant crowds.

- Napoleon Bonaparte launched an effort to reclaim the stolen French property across Europe. He had what is referred to as a “hundred days” reign over France.

- To fight a combined British and Prussian force, the French Army invaded Belgium in 1815. At Ligny, the Prussians were defeated.

- At Waterloo on June 18, the British, under the Duke of Wellington’s command, Arthur Wellesley, with Prussian help, decisively destroyed the French.

- The fight forever eliminated Napoleon’s threat in Europe.

- Napoleon was removed from power once more in June 1815.

Exile on Saint-Helena

- The British imprisoned Napoleon on the Atlantic Ocean island of Saint Helena, 1,870 kilometers off Africa’s west coast.

- To prevent any escape from the island, they also took the precaution of sending a small garrison of soldiers to Saint Helena and the desolate Ascension Island, located between St. Helena and Europe.

- On May 5, 1821, he passed suddenly at 51 while he was there.

- Napoleon Bonaparte was thought to have passed from stomach cancer, although it was rumored that he had been poisoned,

- He requested to be buried on the Seine’s banks but was laid to rest on the island.

- His remains were brought back to France in 1840, where a state funeral was held.

Later Life of Napoleon Bonaparte

- After his defeat at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815, Napoleon was exiled to the remote island of Saint Helena in the South Atlantic.

- During his exile, he lived under strict British supervision and was kept away from political affairs.

- Napoleon spent his time on the island writing his memoirs and reflecting on his life and achievements.

- His health deteriorated during captivity, and he died on May 5, 1821, at 51.

- There are debates and controversies surrounding the cause of his death, with some suggesting he died of stomach cancer or arsenic poisoning.

- Napoleon’s body was initially buried on Saint Helena, but in 1840, his remains were returned to France and laid to rest in a grand tomb at Les Invalides in Paris.

Quotes of Napoleon Bonaparte

- “The only way to lead people is to show them a future: a leader is a dealer in hope.”

- “If you wish to succeed in the world, promise everything, deliver nothing.”

- “Never interrupt your enemy when he is making a mistake.”

- “Envy is a declaration of inferiority.”

- “Most people fail instead of succeed because they trade what they want most for what they want at the moment.”

- Industrial Revolution, in modern history, is the process of change from an agrarian and handicraft economy to one dominated by industry and machine manufacturing. This process began in Britain in the 18th century and from there spread to other parts of the world. Although used earlier by French writers, the term Industrial Revolution was first popularized by the English economic historian Arnold Toynbee (1852-83) to describe Britain’s economic development from 1760 to 1840.

- It was a period during which predominantly agrarian, rural societies in Europe and America became industrial and urban. Prior to the Industrial Revolution, manufacturing was often done in people’s homes, using hand tools or basic machines. Industrialization marked a shift to powered, special-purpose machinery, factories and mass production.

- The iron and textile industries, along with the development of the steam engine, played central roles in the Industrial Revolution, which also saw improved systems of transportation, communication and banking. While industrialization brought about an increased volume and variety of manufactured goods and an improved standard of living for some, it also resulted in often grim employment and living conditions for the poor and working classes.

Changes that Led to Industrial Revolution

- The main features involved in the Industrial Revolution were technological, socioeconomic, and cultural. The technological changes included the following:

- The use of new basic materials, chiefly iron and steel,

- The use of new energy sources, including both fuels and motive power, such as coal, the steam engine, electricity, petroleum, and the internal-combustion engine,

- The invention of new machines, such as the spinning jenny and the power loom that permitted increased production with a smaller expenditure of human energy,

- A new organization of work known as the factory system, which entailed increased division of labour and specialization of function,

- Important developments in transportation and communication, including the steam locomotive, steamship, automobile, airplane, telegraph, and radio, and

- The increasing application of science to industry. These technological changes made possible a tremendously increased use of natural resources and the mass production of manufactured goods

- There were also many new developments in non-industrial spheres, including the following:

- Agricultural improvements that made possible the provision of food for a larger non-agricultural population,

- Economic changes that resulted in a wider distribution of wealth, the decline of land as a source of wealth in the face of rising industrial production, and increased international trade,

- Political changes reflecting the shift in economic power, as well as new state policies corresponding to the needs of an industrialized society,

- Sweeping social changes, including the growth of cities, the development of working-class movements, and the emergence of new patterns of authority, and

- Cultural transformations of a broad order. Workers acquired new and distinctive skills, and their relation to their tasks shifted ; instead of being craftsmen working with hand tools, they became machine operators, subject to factory discipline.

- Finally, there was a psychological change: confidence in the ability to use resources and to master nature was heightened.

Associated Revolutions

Agriculture Revolutions

- The term agricultural revolution refers to the radical changes in the method of agriculture in England in the 17th and 18th centuries. There was a massive increase in agricultural productivity, which supported the growing population. The Agricultural Revolution preceded the Industrial Revolution in England.

- During the Agricultural Revolution, four key changes took place in agricultural practices. They were

- enclosure of lands,

- mechanization of farming,

- four-field crop rotation, and

- selective breeding of domestic animals.

- Prior to the agricultural revolution, the practice of agriculture had been much the same across Europe since the Middle Ages. The open field system was essentially feudal. Each farmer engaged in cultivation in common land and dividing the produce.

- From the beginning of 12th century, some of the common fields in Britain were enclosed into individually owned fields. This process rapidly accelerated in the 15th and 16th centuries as sheep farming grew more profitable. This led to farmers losing their land and their grazing rights. Many farmers became unemployed.

- In the 16th and 17th centuries, the practice of enclosure was denounced by the Church, and legislation was drawn up against it. However, the mechanization of agriculture during the 18th century required large, enclosed fields. This led to a series of government acts, culminating finally in the General Enclosure Act of 1801. By the end of the 19th century the process of enclosure was largely complete.

- Great experiments were conducted in farming during this period. Machines were introduced for seeding and harvesting. Rotation of crops was introduced by Charles Townshend. The lands became fertile by this method.

- Bakewell introduced scientific breeding of farm animals. The horse-drawn ploughs, rake, portable threshers, manure spreaders, multiple ploughs and dairy appliances had revolutionized farming. These changes in agriculture increased food production as well as other farm outputs.

Demographic Revolution

- In 1740s, England witnessed a remarkable growth in her population. This was called as Demographic Revolution (DR).

- So the demand for the commodities increased, this motivated British manufacturers to increase production.

Innovation and Industrialization

- The textile industry, in particular, was transformed by industrialization. Before mechanization and factories, textiles were made mainly in people’s homes (giving rise to the term cottage industry), with merchants often providing the raw materials and basic equipment, and then picking up the finished product. Workers set their own schedules under this system, which proved difficult for merchants to regulate and resulted in numerous inefficiencies.

- In the 1700s , a series of innovations led to ever-increasing productivity, while requiring less human energy. For example, around 1764, Englishman James Hargreaves ( 1722-1778 ) invented the spinning jenny (‘jenny’ was an early abbreviation of the word ‘engine’), a machine that enabled an individual to produce multiple spools of threads simultaneously.

- Another key innovation in textiles , the power loom, which mechanized the process of weaving cloth, was developed in the 1780s by English inventor Edmund Cartwright ( 1743- 1823).

- Developments in the iron industry also played a central role in the Industrial Revolution. Both iron and steel became essential materials, used to make everything from appliances, tools and machines, to ships, buildings and infrastructure.

- The steam engine was also integral to industrialization. By the 1770s, the steam engine went on to power machinery, locomotives and ships during the Industrial Revolution.

Transportation and Industrial Revolution

- The transportation industry also underwent significant transformation during the Industrial Revolution. Before the advent of the steam engine, raw materials and finished goods were hauled and distributed via horse-drawn wagons, and by boats along canals and rivers.

- In the early 1800s, American Robert Fulton built the first commercially successful steamboat, and by the mid- 19th century, steamships were carrying freight across the Atlantic. In the early 1800s, British engineer Richard Trevithick constructed the first railway steam locomotive. In 1830, England’s Liverpool and Manchester Railway became the first to offer regular, time-tabled passenger services.

- By 1850, Britain had more than 6,000 miles of railroad track. Additionally, around 1820, Scottish engineer John McAdam (1756-1836) developed a new process for road construction which made roads smoother, more durable and less muddy.

Communication and Banking

- Communication became easier during the Industrial Revolution with such inventions as the telegraph. A blind English man Rolland Hill (1795-1879) started a system in 1840, through which anybody could send a letter to any place in Great Britain by affixing a one-pence stamp on the letter. In 1844, Samuel Morse invented telegraph machine. In 1876, under water telegraphy was introduced for connectivity between two continents. Underwater cable was laid between North America and Europe and was called ‘Atlantic Cable’. In 1876, Graham Bell invented telephone which revolutionized communication.

- The Industrial Revolution also saw the rise of banks and industrial financiers, as well as a factory system dependent on owners and managers. A stock exchange was established in London in the 1770s; the New York Stock Exchange was founded in the early 1790s.

- In 1776, Scottish social philosopher Adam Smith, who is regarded as the founder of modern economics, published The Wealth of Nations’, which promoted an economic system based on free enterprise, the private ownership of means of production, and lack of government interference.

Quality of Life during Industrialization

- The Industrial Revolution brought about a greater volume and variety of factory-produced goods and raised the standard of living for many people, particularly for the middle and upper classes. However, life for the poor and working classes continued to be filled with challenges.

- Wages for those who labored in factories were low and working conditions could be dangerous and monotonous. Unskilled workers had little job security and were easily replaceable. Children were part of the labor force and often worked long hours and were used for such highly hazardous tasks as cleaning the machinery.

- Industrialization also meant that some craftsman were replaced by machines. Additionally, urban, industrialized areas were unable to keep pace with the flow of arriving workers from the countryside, resulting in inadequate, overcrowded housing and polluted, unsanitary living conditions in which disease was rampant. Conditions for Britain’s working-class began to gradually improve by the later part of the 19th century, as the government instituted various labor reforms and workers gained the right to form trade unions.

Industrial Revolution in England

Reasons for Industrial Revolution in England

- Availability of Capital: The vast amount of capital which England had accumulated out of profits of her growing trade enabled her to make large outlays on machinery and buildings, which in turn contributed to new technological developments. In addition England also possessed a large amount of loanable capital obtained by the bank of England from the rich trade of other countries. Another source of capital for England was her huge colonial possessions.

- Innovation and Scientific Inventions: The Industrial Revolution was stimulated by a number of inventions and developments by British scientists. These inventions were encouraged by freedom of thought. Britain was receptive to intellectual developments from Europe. British thought was secular, rational and focused on science and development. This freedom of thought allowed British scientists to develop new technologies.

- Large Colonial Territories: England had established her extensive colonial empire. In the race for colonisation , France and other states lagged behind. Colonies provided raw materials and new markets to England. England enjoyed monopoly over sea trading. It had the best ports situated on key commercial routes.

- Available Market for Consumption: Towards the middle of the century, a population boom combined with a demand abroad for the products led to the demand needed for a revolution to happen.

- Available Labor Force: Towards the end of 18th century, an epidemic ‘Black death’ broke out in England and lakhs of people died. England became short of farmers and labourers. Thousands of farmers left their villages and came to cities to seek jobs. Due to technological advancements in agriculture also, during early 17th century, many farmers were displaced who started looking for jobs. It increased the number of workers in cities. And they started opening their independent industries.

- Social and Political Stability:

- Britain boasted a remarkably stable government, especially when compared to that of other European nations, who were only beginning to arise from the turmoil created due to over a century of warfare. Other European nations, such as France, Russia and Germany lacked governmental stability due to wars and were more focused on reestablishing their states than industrializing.

- The social stability prevailing in England encouraged the people to invest in sectors where they could hope to receive high dividend in future. This led to the adoption of new techniques and promotion of new industries.

- Availability of Coal and Iron: Britain had huge deposits of both iron and coal, both of which were instrumental to industrialization in general. Iron was used in essentially every tool and machine while coal was utilized to fuel furnaces and factories. With the introduction of the steam engine, coal became even more significant in the industrial process because it fueled locomotives and steamships, both of which were important assets in efficiently transporting goods.

- Protectionist Policy of British Government: Various local taxes and octroi were levied in other European countries but England did not put such barriers. Because of policy of protectionism adopted by British government, trade and industries flourished there.

- Presence of Enterprising People:

- The technological changes in England were made possible because of the presence of a sizable section of people who possessed enterprising spirit and requisite technical qualities.

- Further this class of people were accustomed to handling large enterprises and labour force; were willing to invest money for the discovery of new techniques and give a fair trial to these techniques.

- Risk Taking Private Sector: The presence of the sizable private sector in a country with great capacity of individual businessmen to take risk also greatly contributed to Industrial revolution. These businessmen were willing to take chances on new things. In this they were also supported by the government.

- Better Means of Transport: England possessed a far better means of transportation than any other country in Europe which greatly helped the Industrial revolution. In this task the government played an important role which spent considerable amount on the improvement of roads and construction of canals.

- Geographical Location:

- Being cut off from the mainland of Europe, England remained immune from the wars and upheavals of Napoleonic conflicts and conditions remained quite stable in the country. These stable conditions enabled England to develop its industrial capacity without fear of battle, damage or loss of life.

- Britain’s climate and geography also benefitted their sheep industry and agricultural industry which increased food productions and allowed people to work in the industry.

- Some Other Factors: Unlike France and other countries, serfdom and class system had already been abolished in England. It had an atmosphere useful for the promotion of trade and commerce.

Spread of Industrial Revolution

- In the period between 1760 and 1830, the Industrial Revolution was largely confined to Britain. Aware of their head start, the British forbade the export of machinery, skilled workers, and manufacturing techniques.

- The British monopoly could not last forever, especially since some Britons saw profitable industrial opportunities abroad, while continental European businessmen sought to lure British know-how to their countries .

- Two Englishmen, William and John Cockerill, brought the Industrial Revolution to Belgium by developing machine shops at Liege (c . 1807), and Belgium became the first country in continental Europe to be transformed economically. Like its British progenitor, the Belgian Industrial Revolution centred in iron, coal, and textiles.

- France was more slowly and less thoroughly industrialized than either Britain or Belgium. While Britain was establishing its industrial leadership, France was immersed in its Revolution, and the uncertain political situation discouraged large investments in industrial innovations. By 1848 France had become an industrial power, but, despite great growth under the Second Empire, it remained behind Britain.

- Other European countries lagged far behind. Their bourgeoisie lacked the wealth, power, and opportunities of their British, French, and Belgian counterparts. Political conditions in the other nations also hindered industrial expansion. Germany, for example, despite vast resources of coal and iron, did not begin its industrial expansion until after national unity was achieved in 1870. Once begun, Germany’s industrial production grew so rapidly that by the turn of the century that nation was out producing Britain in steel and had become the world leader in the chemical industries.

- The rise of U.S. industrial power in the 19th and 20th centuries also far outstripped European efforts. And Japan too joined the Industrial Revolution with striking success .

Industrialization in Other Countries

United States of America

- After independence, the USA moved towards industrialization in a phased manner. By the civil war (1861- 65), the USA had become an industrialised nation with the highest Gross National Product (GNP) in the world.

- In the beginning it had to face the following main difficulties in the way of industrialization: lack of capital, shortage of skilled labour, underdeveloped means of transport and ignorance about machines. But because of abundance of natural resources, political stability, government protection and the effort of adventurous entrepreneurs, it soon overcame these difficulties and made rapid progress.

- The main areas were:

Agriculture

- Progress in agriculture provided a strong base to American industrialisation.

- There was a growing demand for the American cotton in the industrial market.

- Harvester and Thresher were invented.

- Rotation of crops was introduced.

- Animal husbandry progressed. Automatic machines were used for cutting and packing meat. Thus, processed food industry considerably grew.

- All these made US a top agricultural country.

Transportation and Communication

- Expansion of transportation and communication played an important role in the economic progress of USA .

- Rapid change was seen in the period between 1789 and 1862.

- Several roads were converted into highways before the end of 18th C. AD.

- In 1825, the longest canal Eirie was built. It connected Albany with Buffalo.

Textile Industry

- Samuel Slater was the founder oftextile industry in America who was called from Britain to set up a spinning jenny and a water frame.

- South New England became the centre of textile industry because the merchants here readily invested their capital in factories and farmers and their families were willing to work in them.

- The factors responsible for this progress were expanding population, custom protection and change in people ’s taste.

Iron and Steel

- Iron and steel is the basis of industrialization.

- In Pennsylvania, the industry developed rapidly as both iron ore and coal were available in plenty.

- Several factories for manufacturing guns and weapons were set up.

- USA adopted the new techniques developed in Britain of iron and steel production.

- Iron and steel were also used for manufacturing Franklin stoves, water pipes and electric poles etc.

Germany

- Industrial revolution in Germany began in 1845 and Berlin, Hamburg, Prague , Vienna were connected by railway lines.

- By 1870 production of iron and steel reached a high point. Several textile mills were set up between 1850 and 1880.

- Transport system was improved.

- Mechanization of industries continued and by 1900 Germany was ready for the takeoff and soon Prussia attained economic leadership.

- Capital investment increased rapidly after 1870 and the population of Germany reached 6.5 million by 1910.

- Before World War I, Germany became an industrial rival of Britain. It left all countries behind in the use of chemicals in agriculture and of science in steel industry.

- In the production of iron and steel, it ranked 2nd after America. Electric goods industry also made rapid progress and enjoyed 50% share in international market.

- The causes of this amazing industrial progress were availability of social capital and its use for building roads, ports, canals and railway lines; expansion of technical education, intelligent use of inventions made in other countries, network of banks and emergence of cartels which maintained the growth rate of the capital and kept the rate of profit high and finally the excellent condition of agriculture.

Russia

- Although it had rich deposits of iron and coal but industrial revolution reached Russia very late because it did not have a good currency system, lacked adequate capital and serfdom still continued there.

- Serfs were freed in 1861 and government invited foreign capitalists to invest in industries.

- The industrial output of Russia rapidly increased between 1860 and 1910.

- During this period, production of iron ore increased tremendously but the engineering industry remained stagnant.

- By 1917, Railways was given more importance and rail network increased to 81000 km.

- More progress was made by Moscow, St. Petersburg and Ukraine.

- Reforms benefitted only a small segment of population. So Russia had all ingredients of becoming an economic power but this was checked by clash of class interests and discontent among the people.

- Lenin’s new economic policy prepared the ground for future development. This policy was continued for 1928 and with the help of five-year plans efforts were made to accelerate economic development.

- The 1st five year plan 1928-1932 laid emphasis on collective farming. The government advanced loans to farmers, supplied them machines and chemical fertilizers on favourable terms and allowed them rebate in taxes.

- The soviet state bought food grains from collective farms at cheaper rates and sold them at higher prices. The difference was utilised for expanding industrialisation.

- One of the drawbacks of economic development during this period was that to meet the targets, the quality of products was compromised. Emphasis on heavy industries created shortage of consumer goods and people had to face rationing and other problems.

Japan

- The Meiji Era (1868 -1912) may be regarded as epoch making in the history of Japan. It was during this period that modernisation of the country took place.

- Japan progressed rapidly after signing of treaty of Kanagawa. In July 1853, the US representative, Commodore Matthew Calbraith Perry , signed the Treaty of Kanagawa with the Japanese government, opening the ports of Shimoda and Hakodate to American trade and permitting the establishment of a U.S. consulate in Japan making the United States the first Western nation to establish relations with Japan since it was declared closed to foreigners in 1683.

- The monetary system was organised and nationalised.

- In 1887 , Yokohama Gold and Silver Banks were established to procure capital for foreign trade.

- Development of Banking system and foreign trade transformed the economy of Japan.

- The government subsidised and encouraged indigenous shipbuilding industry.

- As a result, by the beginning of 10th century, Japan secured foremost position in shipbuilding in the world.

- In 1869, first telegraph line was laid between Tokyo and Yokohama by Mr. Brunton. In 1871, New postal system was introduced in Japan.

- Agricultural reforms were introduced after the reinstallation of Meiji which were: peasants were made owners of land they had been tilling for years; agriculture colleges were opened etc. This further helped Japan in advancing its economy and making Japan the first Asian country to develop.

China

- Civil war broke out in China by the end of World War II and it became a communist country after the revolution of 1949.

- The ownership of the land was given to the farmers and that is how the communist won the popularity among masses.

- China took the help of USSR to modernize its economy and developed shipbuilding industry, organized its air force and rejuvenated its mining activity. Old industries were renovated, means of transport developed and inflation controlled.

- The People’s Bank of China was established to deal with loans and money matters.

- Land was redistributed among the poor and farmers were liberated from exploitation. Land was pooled to make large farms.

- Commune system was introduced which aimed to bring China closer to communism.

- Chinese economy had been socialised to a large extent. Important industries such as petroleum, transport, steel, and communication were nationalised.

- For industrial development, 1st five year plan was initiated. The industrial output recorded an increase of 141% , capital 320% and consumer goods 86% and Chinese goods captured a large market in East Asia.

Effects of Industrial Revolution

- The Industrial revolution in the words of Ramsay Muir was ‘mighty and silent upheaval’ which brought the most momentous change in the condition of human life. Though essentially an economic revolution, it brought significant changes in the social, political and other spheres.

- The trend of economy moved from village to city, from agriculture to industry, from inaction to progress, from small scale to large scale and from national frontiers to international frontiers. In fact no other event in human history of mankind so profoundly affected the human life as the Industrial revolution.

Economic Effects

- It produced far reaching consequences in the economic sphere. In the first place it greatly contributed to the process of humanity through increased production of goods. New factories and workshop came into existence, and produced goods in large quantities with the help of machines.

- These factories operated on the principle of division of labour with each labourer concentrating on some stage of production rather than whole process of production. This not only reduced the cost of goods but also improved their quality.

- Thus industrial revolution made supply of quality goods at cheap rates possible.

- It led to the rise of industrial capitalism and finance capitalism. Before industrial revolution goods were produced at home with the help of simple and cheap tools which did not need much capital. But with the installation of big machines huge capital were needed and a class of capitalist made its appearance .

- Thus, the independent worker became a wage earner, selling his labour to another, and forced to sell it , if he would avoid starvation. Under the factory system women and children became competitors of the men, as they could tend the machines in most industries as well as the men, and would accept lower wages. This dislocation of family from the home to the factory brought with it many evils and abuses, as did also the long hours of labour, the frequent lack of employment, owing to causes which the worker could not control, such as bad management of the business.

- Economic crisis was the inevitable effect of capitalistic economy thus leading to the economic depressions of 1825, 1837 ,1847, 1857, 1866 , 1873, 1888 , 1890, 1900 , 1907 , 1930.

- The industrial revolution provided a boost to trade and commerce. Due to introduction of machines and division of labour, the production of goods increased so much that they could not be consumed by the home market or even by the neighbouring countries. Therefore industrial nations began to look for world markets where their goods could be sold. This resulted in enhancement of trade and commerce, which encouraged Colonisation .

- By bringing the workers together it inevitably led them to organise into unions for the protection and improvement of their individual and collective interests.

Social Effects

- In the social sphere also the Industrial revolution produced far reaching consequences. In the first place, the growth of factory system resulted in the growth of new cities. Workers shifted to places near the factories where they were employed. This resulted in the growth of a number of new cities like Leeds, Manchester, Birmingham etc in Britain, which soon became the centre for industry, trade and commerce.

- The rise of cities was accompanied by growth of slums. Before the advent of industrial revolution, the industries were scattered throughout the country .

- Artisans generally worked in their cottages or shops and were not entirely dependent on trade for their livelihood. They often combined manufacturing and agriculture. This was not possible after the growth of factories as workers had to live at places near to factory. This lead to migration on a large scale from villages to cities and it was a threat to joint family system.

- As a large number of workers had to be provided accommodation, long rows of small one room houses without garden or other facilities were built. With the emergence of new factories and growth in population the problem assumed more serious dimension. In the dark, dingy and dirty houses the workers fell easy prey to various types of diseases and often died premature death.

- The extremely low wages paid by the factory owners made it difficult for them to make both ends meet. As a consequence they were often obliged to send their women and children to factories, where they were work on extremely low wages. The industrialists preferred women and children because they were easy to manage.

- Exploitation of workers especially of women and children resulted in stunted bodies, deformed backs, horribly twisted legs etc. They had to work for 14 to 16 hours. This led to the rise of trade unions. Power of middle class unfolded, power of workers grew. They began to demand respect and fundamental rights. Women also raised demand.

- The conditions of factory life were not conducive to healthy family life. Women were required to work for long hours and they were hardly left with any time or energy to look after their household or children. Further, as they lived in extremely congested quarters they also lost their qualities of modesty and virtue. Often women and children got addicted to alcohol and made their life a miserable one.

- Industrial revolution led to sharp divisions in society. The society got divided into classes – the bourgeoisie and the proletariat. The former consisted of factory owners, great bankers, small industrialists, merchants and professional men. They gathered great wealth and paid very low wages to workers. The other class consisted of labourers who merely worked as tools in the factories.

- With the passage of time the lot of the capitalist classes went on improving and that of the working classes went on deteriorating. This caused great social disharmony, and gave rise to the conflict between the capitalists and workers.

Political Effects

- In the political sphere also, industrial revolution had manifold impact. In the first place it led to the colonisation of Asia and Africa. Great Britain and other industrial countries of Europe began to look for new colonies which could supply them necessary raw materials for feeding their industries and also serve as ready market for their finished industrial products .

- Therefore, the industrial countries carved out extensive colonial empires in the 19th century. These countries added so much of the territories to their empire that one historian has described it as “the greatest land grab movement in the history of the world.” It is well known that the colonialism produced adverse effects on the locals and resulted in their exploitation.

- However, it cannot be denied that it also paved the way for the modernisation of these territories because the Europeans set up certain industrial units in these areas.

- Industrial revolution sharply divided the countries. The industrially advanced countries which possessed necessary finances and skill, invested their surplus capital in backward countries and fully exploited their resources and crippled their industries. Thus the world came to be divided into two groups- the developed and the underdeveloped world, which is a cause of great tension even at present.

- As a result of Industrial Revolution, a large number of Europeans went across the oceans and settled down in America and Australia and contributed to the Europeanisation of these countries. It has been estimated that as against 145,000 people which left Europe in 1820s, over 9 million people left Europe between 1900 and 1910.

- It also provided the boost to the reform movements in England. Many factory laws were enacted to improve the lot of the workers between 1833-45 which tried to limit the working hours for children under eleven years of age to nine hours a day and that of women to 12 hours a day. These Acts also prohibited employment of children in mines and laid down general rules for the health and safety of workers.

- With the setting up of factories in northern part of England larger number of people shifted from south and their population greatly declined. However, these populated cities continued to send same number of representatives to the parliament whereas the new industrial towns were not represented in the parliament. This led to the demand of redistribution of seats. A movement known as Chartist movement began to demand reforms for improving the lot of workers and for introduction of universal suffrage, secret voting, equal electoral districts, no property qualifications for membership, payment of members, and annual elections. In this way we can say that the industrial revolution strengthened forces of democracy in England.

Ideological Effects

- Industrial revolution left a remarkable effect on economic ideology also. In the 18th century, liberalism which was based on the principle of individual liberty prevailed in Europe.

- Liberalism was a political concept and involved constitutionalism, supremacy of the public, equality of all before law, religious tolerance and understanding of nationalism. Industrial revolution in England added the principle of non-interference by the state in economic affairs.

- Adam Smith subscribed to the policy of laissez-faire and pointed out the useless role of state’s control over trade and commerce.

- David Ricardo maintained that every national economy is based on certain eternal laws and the ‘Iron law of Wages’ is one of them. According to this law, it is not possible for a worker to earn more than his livelihood.

- The British government formulated its economic policies on the basis of laissez-faire. British Industrialists also welcomed those policies because the system of capitalism based on free competition enjoyed their support.

- The spirit of public welfares and efforts for improving the condition of workers gave birth to socialism. Socialism aimed at establishing equality in society.

- The ultimate goal of socialism was to eliminate class struggle and form a classless society. In order to achieve these objectives, government’s control over production and distribution of important things was considered necessary.

- Socialism has Three Pillars

- It criticizes modern industrial civilization-private capitalism.

- It is the voice of all workers and working class.

- Demands a just distribution of wealth.

Industrial Revolution: A Critical Analysis

Merits

- Urbanisation: The factory system introduced by the Industrial Revolution created cities and urban centres. In England , cities like Manchester, Birmingham , Leeds, and Sheffield arose . People left their rural homes and gathered around these cities by the hundreds and thousands in quest of work and wages. The population of Manchester increased six fold within a half century.