Geography – 3rd Year

Paper – III (PYQs Soln.)

2 Marker Questions

Language/भाषा

Population geography relates to variations in the distribution, composition, migration, and growth of populations. Population geography involves demography in a geographical perspective. It focuses on the characteristics of population distributions that change in a spatial context. This often involves factors such as where population is found and how the size and composition of these population is regulated by the demographic processes of fertility, mortality, and migration.

Contributions to population geography are cross-disciplinary because geographical epistemologies related to environment, place and space have been developed at various times. Related disciplines include geography, demography, sociology, and economics.

History

Since its inception, population geography has taken at least three distinct but related forms, the most recent of which appears increasingly integrated with human geography in general. The earliest and most enduring form of population geography emerged in the 1950s, as part of spatial science. Pioneered by Glenn Trewartha, Wilbur Zelinsky, William A. V. Clark, and others in the United States, as well as Jacqueline Beaujeu-Garnier and Pierre George in France, it focused on the systematic study of the distribution of population as a whole and the spatial variation in population characteristics such as fertility and mortality. Population geography defined itself as the systematic study of:

- the simple description of the location of population numbers and characteristics

- the explanation of the spatial configuration of these numbers and characteristics

- the geographic analysis of population phenomena (the inter-relations among real differences in population with those in all or certain other elements within the geographic study area).

Accordingly, it categorized populations as groups synonymous with political jurisdictions representing gender, religion, age, disability, generation, sexuality, and race, variables which go beyond the vital statistics of births, deaths, and marriages. Given the rapidly growing global population as well as the baby boom in affluent countries such as the United States, these geographers studied the relation between demographic growth, displacement, and access to resources at an international scale.

Arithmetic Density: This is the most common measure, calculated by dividing the total population by the total land area. It provides a straightforward measure of population distribution but does not consider variations in land usability.

Physiological Density: This type measures the population relative to the arable land area, offering a better understanding of the pressure on productive land. Regions with high physiological density may struggle to produce enough food for their population.

Agricultural Density: This focuses on the ratio of farmers to arable land, reflecting the efficiency of a region’s agricultural practices. Lower agricultural density often indicates advanced farming technologies, while higher density may suggest subsistence farming practices.

Urban Density: This refers to the population within urbanized areas, highlighting patterns of urbanization and city planning. It is critical for managing urban resources and infrastructure effectively.

Residential Density: This considers the number of people living in residential areas, offering insights into housing and settlement patterns.

Understanding these types of population density is crucial for policymakers and planners in addressing challenges like overcrowding, resource distribution, and sustainable development. Each type provides unique perspectives to evaluate human interaction with the environment and land resources.

Underpopulation means when a country’s population is fewer than required for development. It can lead to problems like a shortage of human resources and labour, an ageing population, low economic growth, etc.

Causes of Under Population

In some places, the population is not optimum. Many things can cause underpopulation.

- Natural disasters like earthquakes, floods, famines and epidemics can cause people to die. This reduces the population.

- Volcanic eruptions destroy homes. People leave as they cannot stay after eruptions.

- People move away from dry, desert areas with scarce resources. Fewer babies are born where conditions are tough.

- Few jobs mean fewer people want to stay. They move to find work elsewhere.

- No jobs make it hard for young people to begin families. This lowers birth rates.

- Little fresh water and fertile land limit how many people an area can support. Some move away.

- Isolated areas with few roads have trouble attracting new people.

- Poor internet and phone connectivity keep people from moving in. This shrinks populations.

- When medical care is not readily available, more babies and people die. This decreases the population.

- Too much violence and crime chase people out of areas. They move to safer places to live.

- When cities become too pricey, many residents leave to find cheaper places to live. This reduces the population.

- Governments can create policies that limit who can live in areas. Immigration restrictions lower the population.

- When an area has little economic activity and work, people leave for jobs elsewhere. This lowers populations.

- Poor education systems make families go elsewhere. They want good schools for their children. This reduces numbers.

- Some people choose to leave busy, crowded cities and suburbs. They move to less populated rural areas.

- The main things that cause underpopulation in places are natural disasters, lack of jobs, poor infrastructure, bad healthcare, violence, high costs, government policies and few opportunities. When these issues make life hard, people leave areas. This decreases populations and causes underpopulation.

Effects of Under Population

When an area has fewer people than normal, certain consequences result. This phenomenon of underpopulation brings about various impacts.

- With fewer people, there is a smaller demand for goods and services.

- Businesses have trouble making profits as the population falls. Some stores close down.

- Fewer taxpayers mean lower tax revenues for governments. This hurts funding for public services.

- Fewer workers are available to fill jobs. Companies struggle to find enough employees.

- Decreased economic activity slows the development and growth of underpopulated areas.

- Less demand for housing keeps property values from rising much.

- With fewer businesses, less competition forms. This limits choices and options for people.

- Public services often get cut due to a lack of funds from lower tax revenues.

- Health care and education quality can suffer with too few doctors, nurses and teachers per resident.

- It costs governments more per person to provide services in underpopulated areas.

- The prices of goods tend to be higher due to a lack of scale for businesses.

- It is harder for companies to spread fixed costs like rent and equipment across many customers.

- Governments have trouble maintaining underused roads, water systems and public buildings.

- Few people generate a reduced need for utilities like electricity, water treatment and internet services.

- Transportation options dwindle as there are insufficient passengers or customers to make robust systems viable.

- Retired people and slow population growth mean fewer younger, qualified workers.

- Universities, colleges and training centres face declining enrollments.

- The skills and knowledge of those who leave are lost to underpopulated areas.

- Fewer people limit dating prospects and options for making friends.

- Less cultural and recreational activities form due to small customer bases.

- Neighbourhoods become less tight-knit, with fewer residents to interact with.

- There are proportionally more elderly and young people relative to working-age residents.

- This means fewer people must support more retirees and children.

- Abandoned homes and empty lots in underpopulated towns create eyesores.

- Public areas like parks suffer when smaller populations cannot maintain them.

- Unused farmland reverts to wilderness and becomes overgrown.

- The primary effects of underpopulation in places include economic problems, lower living standards, higher costs, infrastructure challenges, loss of skilled workers, limited social opportunities, higher dependency and environmental impacts. All of these consequences stem from having too few people living in an area.

Advantages And Disadvantages Of Underpopulation

Here’s a table outlining the advantages and disadvantages of underpopulation:

Advantages | Explanation | Disadvantages | Explanation |

Greater resource availability | With fewer people, there is less demand for resources such as food, water, and energy. This can lead to an abundance of resources per capita, resulting in higher standards of living. | Decline in economic growth | A significant decline in population can lead to reduced economic growth. A smaller workforce may result in decreased productivity, innovation, and consumer demand, impacting industries and overall economic development. |

Reduced strain on infrastructure | Underpopulation can relieve pressure on infrastructure systems such as transportation, healthcare, and education. With fewer people to serve, it becomes easier to maintain and upgrade infrastructure efficiently. | Aging population and strained healthcare systems | Underpopulation often leads to an aging population, which can strain healthcare systems and social welfare programs. The ratio of elderly individuals to working-age individuals may increase, putting pressure on pensions and healthcare funding. |

Less environmental impact | Lower population density can lead to reduced environmental impact, including less pollution, decreased deforestation, and improved biodiversity. It allows for better conservation of natural resources and habitats. | Limited workforce and skill shortages | With fewer people available in the workforce, there may be skill shortages in various sectors. This can impact productivity, hinder technological advancements, and limit the ability to meet the demands of a changing economy. |

Lower unemployment rates | In an underpopulated society, there are fewer people competing for available jobs. This can result in lower unemployment rates and potentially lead to higher wages and better working conditions. | Decreased cultural diversity | Underpopulation can lead to a decline in cultural diversity and a loss of unique traditions and languages. Smaller communities may struggle to preserve their cultural heritage and maintain social cohesion. |

Increased personal freedom | With a smaller population, individuals may experience greater personal freedom and autonomy. There can be more space for self-expression, creativity, and exploration of diverse lifestyles and cultural practices. | Increased burden on individuals | In an underpopulated society, individuals may face increased burdens and responsibilities. There may be fewer support systems in place, leading to a heavier workload for each person in terms of caregiving, community participation, and other societal roles. |

Conclusion

Underpopulation poses serious challenges to the development of a country. The government must focus on all measures like increasing fertility rates, reducing female foeticide, skill development and job creation to reverse this problem and achieve balanced population growth in the future. With better policies and initiatives, the country can turn underpopulation into an opportunity to boost its economy and human development indices.

As populations grow, the demand for resources increases, often leading to resource depletion, environmental degradation, and competition for scarce resources. For example, overpopulation in certain regions can strain water supplies, agricultural production, and energy systems, leading to food insecurity, rising prices, and social tensions. Conversely, areas with small populations and abundant resources may experience underutilization, which can hinder economic development.

The relationship is also shaped by the carrying capacity of the environment, which refers to the maximum number of individuals an area can support without depleting its resources. Exceeding this capacity can result in ecological imbalances and a decline in living standards.

Technological advancements play a critical role in mediating this relationship by improving resource extraction, production efficiency, and sustainable consumption. However, unequal access to technology and resources often exacerbates global disparities, with some regions facing acute shortages while others overconsume.

Effective policy interventions are essential to address population-resource challenges. Strategies such as promoting renewable energy, improving agricultural productivity, implementing population control measures, and encouraging sustainable practices can help align resource availability with population needs. A balanced approach ensures that human well-being and environmental integrity are maintained for future generations.

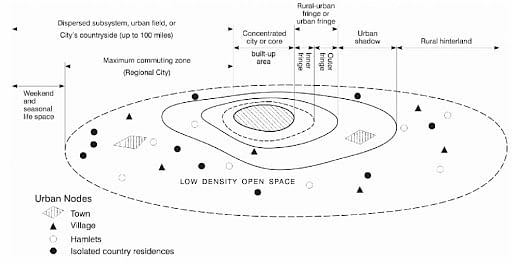

Urban fields refer to the spatial and functional areas influenced by a city, encompassing its urban core and the surrounding regions that are economically, socially, and functionally connected to it. These fields are shaped by urbanization processes and highlight the dynamic interaction between the city and its hinterland. They play a crucial role in regional development, resource distribution, and social integration.

The urban core is the central area of high population density and concentrated economic activities, often serving as the hub for governance, commerce, and cultural institutions. Surrounding the core, the urban fringe or peri-urban areas exhibit a mix of urban and rural characteristics, where urban expansion meets traditional rural landscapes. These areas are critical for accommodating urban growth, housing developments, and infrastructure expansion.

Urban fields are also defined by functional linkages such as transportation networks, trade, communication, and the flow of goods, services, and people. The extent of an urban field depends on the size and influence of the city. For example, global cities like New York or London have extensive urban fields that extend internationally, while smaller cities have more localized fields.

Understanding urban fields is essential for regional planning and sustainable urban development. Proper integration of the core and peripheral areas ensures balanced growth, minimizes environmental degradation, and promotes social equity. Policymakers use the concept of urban fields to address challenges like urban sprawl, resource allocation, and connectivity, ensuring that both urban and surrounding rural areas benefit from development.

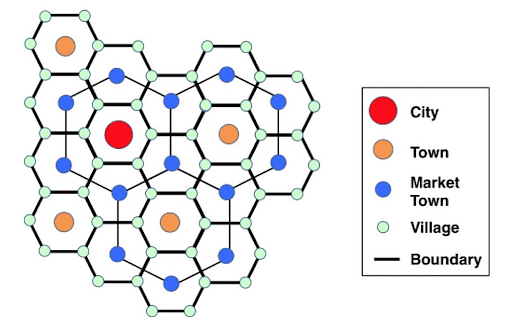

In geography, the hierarchy of urban settlements refers to the ranked order of cities and towns based on their size, function, and interaction. Larger cities have more complex functions and dominate smaller places in the hierarchy.

History Of Urban Settlements

The hierarchy of urban settlements has changed over time. Some urban centers have grown as they took control of trade and resources, while others have declined.

- Cities first started developing around 5,000 years ago. Early settlements centered around natural resources like rivers and farmland. As cities grew, a hierarchy of urban settlements formed based on size, political control, and specialization of economic functions.

- The first cities were small, with only a few thousand residents. They functioned as religious and administrative centers and controlled nearby agricultural land. These early urban settlements were part of the hierarchy of urban settlements as towns.

- As trade and empire-building expanded over thousands of years, some towns became primate cities that dominated the hierarchy of urban settlements. These cities had tens of thousands of residents and controlled long-distance trade networks. They collected taxes from subject towns and used the wealth to build important government buildings and cultural sites. Primate cities dominated the urban hierarchy of their time.

- Specialization of functions also defined the hierarchy of urban settlements. Some urban centers specialized as trading ports, while others functioned as industrial or administrative centers. Within the overall urban hierarchy, settlements specialized in specific economic activities that supported and interconnected with each other.

- In Europe, Rome emerged as a primate city dominating the urban hierarchy during the Roman Empire around 1500 years ago. At its peak, Rome had over 1 million residents and controlled the political and economic activities of millions across Europe and the Mediterranean. When the Roman Empire declined in the West, Rome’s control over the urban hierarchy also declined.

- During the Middle Ages in Europe, the hierarchy of urban settlements changed again. Many towns became smaller industrial or market centers, while primate cities became rare. Investment shifted from urban infrastructure to the Church and monarchy. This fragmented urban hierarchy lasted for hundreds of years.

- The industrial revolution starting around 200 years ago, transformed the urban hierarchy again. New industrial cities like Manchester and Birmingham in England rapidly grew based on their industrial specialization. As industrial cities formed new regional urban hierarchies, primate cities re-emerged, like London in the United Kingdom. Transportation improvements allowed primate cities to coordinate economic activities across wider regions.

- Today, cities have continued growing, and the hierarchy of urban settlements has become more complex with globalization. Mega-cities with over 10 million residents have emerged that dominate global urban hierarchies through control of information, finance, and innovation. At the same time, smaller cities and towns continue serving as industrial, administrative, or retirement centers within national urban hierarchies.

- In summary, the hierarchy of urban settlements has shifted over thousands of years based on control of resources, political power, and specialization of economic functions. As urban networks have expanded from local to global scales, the most dominant cities in the urban hierarchy have gained more influence over political and economic systems. Still, urban hierarchies remain dependent on smaller settlements specializing in important supporting activities. The future evolution of the hierarchy of urban settlements will likely continue to transform based on technological changes and the emergence of new global challenges.

Types

The hierarchy of urban settlements can be divided into multiple categories based on factors like population size, level of development, and functions performed. Here are the main types of urban centers:

- Large Cities: Large cities, also known as metropolitan areas, are the most developed and populous urban centers. They typically have over a million residents and are characterized by high levels of economic, political, and cultural importance. Large cities offer the most advanced facilities and opportunities.

- Regional Hubs: Regional hubs, or regional centers, serve as economic and administrative focal points for their surrounding areas. They tend to have populations ranging from 100,000 to a million people and play an essential role in organizing and promoting development within their regions. They provide many important services and amenities for the region.

- Middle-Sized Towns: Middle-sized towns, also called intermediate centers, are urban settlements larger than villages but smaller than regional hubs. They tend to have populations from 10,000 to 100,000 residents and play an important part in providing local services and driving economic and social progress within their immediate areas. They link villages to regional hubs.

- Small Villages: Small villages constitute the least developed urban centers. They tend to have populations anywhere from a few hundred to 10,000 residents and are characterized by low levels of economic activity and influence. They primarily provide basic services and facilities to meet the essential needs of their residents. Villages depend on larger towns and cities for many services.

- In summary, the hierarchy of urban settlements ranges from small villages at the bottom to large metropolitan areas at the top. As you move up the hierarchy, urban centers provide more advanced facilities, functions, and opportunities due to their increased population size, development, and importance.

Examples

- Metropolitan areas are the largest and most developed urban centers in a region. They contain massive populations and a wide range of economic and political functions. Cities like New York City, Tokyo, and Mumbai exemplify metropolitan areas. They contain millions of residents and serve as hubs for business, transportation, entertainment, and government for their entire regions.

- Regional centers, though smaller than metropolitan areas, still serve important functions for their regions. They act as economic and political hubs, providing jobs, commerce, and services that support surrounding areas. Cities like Manchester in England and San Francisco in California are examples of large regional centers. They have hundreds of thousands of residents and attract people from surrounding towns and rural areas for economic opportunities and cultural activities.

- Intermediate centers typically play a more localized role in their region’s economic and social development. Though smaller than regional centers, they still have substantial populations and businesses that provide jobs, services, and amenities for surrounding rural areas. Austrian cities like Salzburg and English villages like Cheltenham exemplify intermediate centers. They have populations in the tens of thousands and enough economic activity to draw residents from neighboring rural towns.

- Small towns and villages tend to have much lower levels of economic activity and political influence compared to larger urban areas. They typically provide basic services and jobs for immediately surrounding rural populations but do not significantly impact regions. English villages like Cirencester and California towns like Mendocino exemplify small towns and villages. They have relatively small populations and economic and political roles that are limited to their town boundaries.

Issues With Hierarchy Of Urban Settlements

The hierarchy of urban settlements shows how cities and towns rank based on size, population, and importance. However, this hierarchy has several problems.

- For one, it treats all cities and towns as economic units instead of communities where people live. It focuses on rankings based on economic output, importance as a center of trade, and population size. But cities and towns are more than economic units. They are places where people build homes and lives.

- The hierarchy also ignores factors like quality of life, sustainability, and equality. Smaller towns and villages often have better environments, lower costs of living, and closer-knit communities. But the hierarchy values economic output and political influence over liveability.

- The hierarchy can contribute to the overdevelopment of larger cities. As cities move up the hierarchy, they receive more investment and resources. But this continuous growth does not consider the environmental impact or population pressures on infrastructure. It encourages the unsustainable growth of “successful” cities.

- The hierarchy does not consider equality between urban settlements. Areas lower on the hierarchy receive less investment and have fewer jobs and opportunities. This leads to inequality in access to resources between larger and smaller urban settlements.

- The rigid rankings in the hierarchy are also unrealistic. Many small towns now have global economic connections. And some regional centers now face issues commonly associated with larger metropolitan areas. The lines between rankings are blurring.

- A better approach would value all urban settlements for the communities they provide rather than just their economic output. It would distribute resources based on the needs of communities rather than hierarchy. And it would promote sustainable growth for urban settlements of all sizes.

In geography, the term K-7 typically refers to the seven key concepts that form the foundation for understanding geographical studies. These concepts provide a framework to analyze and interpret the interaction between humans and the environment, as well as spatial patterns and processes. The K-7 concepts are:

Place: Refers to specific locations on Earth that have unique physical and human characteristics. Understanding place involves exploring what makes a location distinct and how it connects to other places.

Space: Focuses on the arrangement of features on Earth’s surface, examining patterns of distribution, density, and movement. It helps in analyzing how resources, populations, and activities are distributed geographically.

Environment: Examines the relationship between humans and their surroundings, including natural and built environments. It emphasizes the importance of sustainable interaction with the environment.

Scale: Considers the level of analysis, from local to global, to understand geographical phenomena. Scale helps in linking small-scale processes to larger systems and vice versa.

Interconnection: Highlights the connections and relationships between people, places, and environments. This includes economic, cultural, and environmental linkages that shape global systems.

Change: Focuses on the dynamic nature of places and environments over time. It helps in understanding the causes and consequences of both natural and human-induced changes.

Sustainability: Emphasizes the need for responsible management of resources and environments to ensure they are available for future generations.

These concepts collectively guide geographical inquiry and foster a holistic understanding of the complex interactions that shape our world. They are crucial for addressing contemporary challenges such as climate change, urbanization, and global inequalities.

In the complex, ever-evolving terrain of urban studies, one concept stands apart for its ability to decode the structural makeup of our cities: Urban Morphology. This unique field is to urban planning and design what genetics is to biology. By dissecting the urban fabric, urban morphology unlocks an intimate understanding of the DNA of our cities, paving the way for better-informed decisions on sustainable urban growth and development.

What is Urban Morphology?

Broadly, urban morphology refers to the study of the physical form and structure of cities. It’s an amalgamation of insights from various disciplines including geography, architecture, planning, and social sciences. By evaluating the interplay between the built environment and socio-economic forces, urban morphology elucidates patterns and processes shaping the spatial configurations of cities.

In essence, this discipline acts as a microscope that magnifies our understanding of the urban fabric — the street patterns, the building designs, the public spaces, and more. It’s through this intricate lens that we can perceive the dynamism of urban evolution and reinterpret the cityscape in the light of the past, the present, and the future.

History of Urban Morphology: Tracing the Evolution of Urban Studies

Delving into the study of urban morphology is akin to embarking on a fascinating journey through time. By understanding the genesis and progression of this discipline, we not only gain valuable insights into the foundations of our modern cities but also acquire a robust framework to comprehend their present intricacies and future trajectories.

Urban morphology, as a distinct field of study, first germinated in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. However, the underpinnings of the discipline trace back to ancient civilizations. The planned cities of the Harappan civilization, the gridiron plan of Roman cities, or the organically evolved medieval cities — all reflect an implicit understanding of what we now recognize as principles of urban morphology.

In the modern academic landscape, two schools of thought emerged predominantly in the study of urban morphology – the Italian school, led by Saverio Muratori, and the British school, steered by M.R.G Conzen. While the Italian school focused on the historical fabric of the cities and viewed the city as a living organism, the British school, on the other hand, emphasized the geographical aspects of urban development, analyzing the patterns of land use and building forms over time.

In the 20th century, urban morphology experienced a renaissance as urban issues gained prominence against the backdrop of rapid urbanization and industrialization. The discipline began to incorporate insights from related fields such as sociology, economics, and environmental science, evolving into an interdisciplinary domain.

Today, the field of urban morphology continues to be an essential pillar of urban studies, contributing significantly to the sustainable planning and development of our cities. By understanding its history, we can appreciate the rich tapestry of influences that have shaped it and leverage its lessons to forge a brighter urban future.

Elements of Urban Morphology

Underneath the surface complexity of the urban landscape are fundamental building blocks, the primary elements of urban morphology. Each element represents a different facet of a city’s physicality and functionality.

- Streets: The arteries of a city, defining connectivity and accessibility.

- Blocks: Defined by the network of streets, they house diverse urban activities.

- Buildings: From residential homes to towering skyscrapers, they shape the city’s skyline and define its character.

- Open Spaces: Public spaces like parks and plazas, contributing to a city’s livability.

- Land Use: Defines the distribution of various activities such as residential, commercial, industrial, and so on.

By closely studying these elements, we can unravel the urban structure, pinpoint its strengths and weaknesses, and work towards creating more livable, sustainable cities.

Different Types of Models in Urban Morphology: Unraveling Urban Patterns

The study of urban morphology involves deciphering the city’s form and structure. But given the complexity and diversity of cities, is there a unifying framework or model that we can use? Thankfully, urban morphology offers several models that encapsulate typical patterns of urban development. Let’s delve into some of the key models that help us understand and predict the spatial form and growth of cities.

- Concentric Zone Model: Proposed by sociologist Ernest Burgess in 1925, this model visualizes the city as a series of concentric circles radiating from a central business district (CBD). The model highlights the influence of socio-economic factors on the spatial organization of cities.

- Sector Model: Developed by Homer Hoyt in 1939, this model portrays cities as pie-shaped sectors radiating from the CBD. According to Hoyt, certain areas of a city are more attractive for various uses, leading to a sectoral distribution of similar land uses.

- Multiple Nuclei Model: Harris and Ullman’s 1945 model suggests that cities develop around several nodes or nuclei, each with its own specialty. These could be a CBD, a university, an industrial park, or a residential suburb.

- Urban Realms Model: Proposed by James Vance in 1964, this model describes the city as a collection of self-sufficient, semi-independent ‘realms,’ each with its own economic, social, and political entity.

- Bid-Rent Theory: This model, developed by William Alonso in 1964, explains the spatial organization of cities based on economic theory. It postulates that land values decrease as one moves away from the CBD, impacting the location of different land uses.

- Edge City Model: Garreau’s 1991 model recognizes the significance of suburban nodes. The ‘edge cities’ are described as a major concentration of retail and office space situated on the periphery of older urban areas.

It’s important to remember that while these models provide a simplified representation of urban morphology, they may not fully encapsulate the unique complexities of every city. Urban morphology is an evolving field, continually adapting to the changing dynamics of urban development. However, these models still serve as valuable tools, helping us analyze, interpret, and envision the urban landscape.

Shape and Structure of Urban Areas: Architecting the Urban Landscape

A distinctive aspect of urban morphology lies in its examination of the shape and structure of urban areas. This feature embodies the patterns and forms that lend cities their unique physical identity. Grasping this aspect is pivotal to understanding the nature and character of cities.

Urban Shape

Urban shape refers to the overall form or outline of an urban area. It is an overarching parameter that provides a bird’s-eye view of the city. Shapes of cities have been influenced by various factors over the course of history: topographical constraints, technological advancements, socio-cultural evolution, and economic factors.

Cities can be classified into several typical forms based on their shape:

- Linear Cities: These are stretched along a line, often a river, coast, road, or railway. An example is the Nile Valley in Egypt.

- Star-shaped Cities: These cities grow radially from a central point, like spokes on a wheel. Paris, with its boulevards radiating from the Arc de Triomphe, is a classic example.

- Circular or Ring Cities: These are shaped around a central core. The Ringstrasse in Vienna reflects this pattern.

- Gridiron Cities: Characterized by a network of perpendicular streets, these cities were prevalent in ancient Rome and later adopted in many American cities like New York.

- Organic Cities: These have evolved gradually over time, often with winding streets and irregular patterns. Many medieval European cities, such as Venice, show this characteristic.

Urban Structure

Urban structure refers to the internal layout or arrangement of different components within a city. It captures the organization of land use, the layout of streets, the arrangement of buildings, and the distribution of open spaces.

Understanding the structure of urban areas involves studying:

- Street Patterns: This includes grid patterns (as in Manhattan), radial patterns (as seen in Moscow), or irregular patterns (as found in many ancient cities).

- Building Patterns: How are buildings arranged? Are they densely packed, or is there significant open space? Are they low-rise or high-rise?

- Land Use Distribution: This pertains to the spatial allocation of residential, commercial, industrial, and recreational zones.

- Transportation Network: The layout and connectivity of roads, railways, airports, and ports define the accessibility and mobility within a city.

By studying the shape and structure of urban areas, urban morphology provides a blueprint of the city. It lays bare the inherent logic of urban growth and organization, assisting planners, architects, and policymakers in making informed decisions for the future of our cities.

Factors Affecting Urban Morphology

Urban morphology doesn’t exist in isolation; it is continually shaped and reshaped by a multitude of external influences. Here are some key factors affecting urban morphology:

- Historical Context: Cities, like organisms, evolve over time. Each phase of development leaves its mark on the urban fabric, influencing its form and function.

- Geographical Constraints: The physical geography of a location, including topography and climate, often dictates the shape and structure of cities.

- Socio-economic Forces: Market dynamics, population growth, and societal norms can lead to urban transformations.

- Political Decisions: Policies and planning decisions play a crucial role in shaping the cityscape.

- Technological Innovations: From the advent of railways to the rise of the internet, technology impacts how cities grow and adapt.

Understanding these factors, their interconnections and implications can lead to better urban planning strategies, making our cities more resilient and inclusive.

Population planning refers to the strategies and policies implemented by governments and organizations to regulate population growth and ensure a balanced relationship between population size and available resources. It is essential for addressing challenges related to overpopulation, resource scarcity, and sustainable development.

The primary goal of population planning is to promote economic stability, improve living standards, and ensure the equitable distribution of resources. This is achieved through measures such as family planning programs, promoting reproductive health awareness, and encouraging the use of contraceptives to enable individuals to make informed decisions about family size.

In countries experiencing rapid population growth, population planning focuses on reducing the fertility rate through education, particularly for women, as well as improving access to healthcare and economic opportunities. Conversely, in countries facing population decline, policies may include incentives for higher birth rates, such as tax benefits, paid parental leave, and childcare support.

Population planning also involves managing the impact of demographic changes, such as urbanization and aging populations. For instance, policies may address urban infrastructure needs or reform pension systems to accommodate an increasing proportion of elderly citizens.

Effective population planning requires collaboration between governments, non-governmental organizations, and international agencies. It also considers cultural and social factors to ensure that policies are inclusive and respectful of human rights. By aligning population dynamics with development goals, population planning plays a critical role in building resilient societies and ensuring a sustainable future.

Types of settlement refer to the classification of human habitation based on their size, function, and spatial organization. Settlements serve as the foundation of human activity, reflecting the relationship between people and their environment. They can be broadly categorized into rural and urban settlements, with further subcategories based on their characteristics.

Rural Settlements: These are typically small in size and focus on agriculture and primary activities. They are further classified into:

- Compact Settlements: Characterized by closely spaced houses and a high population density. These are common in fertile agricultural regions, where land is intensely cultivated.

- Dispersed Settlements: Marked by scattered houses, often found in areas with difficult terrain, poor soil fertility, or forested regions. Examples include settlements in hilly areas or deserts.

- Linear Settlements: Arranged in a line along natural or man-made features like rivers, roads, or railway lines.

Urban Settlements: These are larger and focus on secondary and tertiary activities like industry, trade, and services. They are categorized into:

- Towns: Intermediate in size, serving as administrative or market centers.

- Cities: Larger settlements with diverse economic activities and infrastructure.

- Metropolises: Very large cities with populations in the millions, acting as hubs for national or international activities.

- Megalopolises: Formed by the merging of several large cities, creating vast urban corridors.

Settlements evolve based on factors like natural resources, climate, and economic opportunities. Understanding the types of settlement helps in regional planning, resource management, and addressing challenges like urban sprawl and rural depopulation. These classifications are essential for sustainable development and enhancing the quality of life in different habitation types.

The functional classification of towns is a useful geographic tool for classifying urban settlements. This classification is based on the functions the towns perform and the services they provide. This helps understand the various roles and importance of different towns within a country.

What is the Functional Classification of Towns?

Functional classification of towns is a method of categorizing urban centers based on their primary functions and specializations. This classification system helps to understand the different roles that cities play within a region or country. Towns can be classified into various categories based on their functions. This includes administrative towns, mining towns, industrial towns, tourist towns, commercial towns, and transport towns, among others.

Quantitative and Qualitative Methods of Functional Classification of Towns

There are two main methods used for the functional classification of urban areas: quantitative and qualitative.

- Quantitative methods use statistical data to classify towns. This data can include information on the following:

- the size of the town,

- the number of people employed in different industries, and

- the level of education in the town.

- Qualitative methods use expert knowledge to classify towns. This knowledge can come from geographers and economists who study urban development.

Christaller’s Central Place Theory

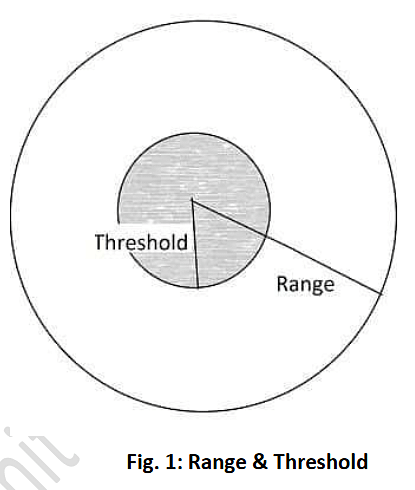

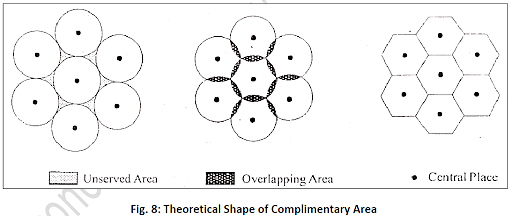

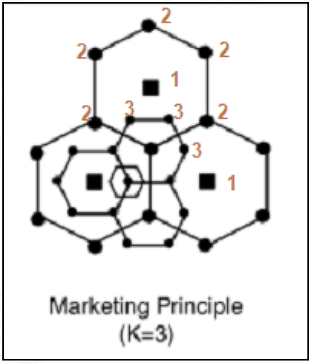

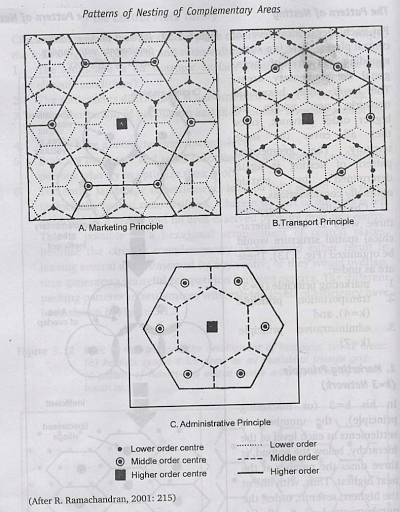

Walter Christaller’s central place theory from 1933 forms the basis for the functional classification of urban areas. As per this, settlements develop ‘central functions’ of providing goods and services to their ‘hinterland’. The variety of central functions determines their ‘order’ or level.

Different Orders of Towns as per Christaller

- First-order towns – Provide immediate daily needs to their rural surroundings.

- Second-order towns – Provide specialised goods and services in addition to the functions of first order towns. They cater to a larger hinterland.

- Third-order towns – Have the widest range of specialised institutions. They cater to an even larger hinterland. They become sub-regional or regional centres.

- Fourth and higher-order towns – Perform more specialized functions at national and international levels.

Popular Functional Classification of Towns

Here are some of the most well-known functional classifications of towns:

M. Aurousseau’s classification (1921)

Aurousseau’s classification is based on the primary functions of towns. He classified towns into six categories. This classification is one of the most comprehensive. Geographers have used it for many years. The six categories are:

- Administrative: Towns that serve as the administrative hub for a region or country.

- Defense: Towns that are important for military purposes.

- Cultural: Towns that are home to cultural institutions. This includes museums, theaters, and libraries.

- Production: Towns that are home to industries such as manufacturing, mining, and agriculture.

- Communication: Towns that are important transportation nodes. This includes airports, train stations, and seaports.

- Recreation: Towns that are popular tourist destinations.

Harris’s Classification (1943)

Harris’s classification is based on the economic activities of towns. He classified towns into nine categories. This classification focuses on the quantitative analysis of urban functions. The nine categories are:

- Manufacturing: Towns that are home to manufacturing industries.

- Retailing: Towns that are home to retail businesses, such as shops and supermarkets.

- Diversified: Towns that have a mix of economic activities.

- Wholesaling: Towns that are home to wholesale businesses such as distribution centers.

- Transportation: Towns that are important transportation nodes.

- Mining: Towns that are home to mining industries.

- Educational: Towns that are home to colleges, universities, and other educational institutions.

- Resort or retirement: Towns that are popular tourist destinations or retirement communities.

- Others: Towns that do not fit into any of the other categories.

Howard Nelson’s Classification (1955)

Howard Nelson’s classification focuses on the qualitative aspects of urban areas. Nelson classified towns into four categories. This classification is based on the functions of towns and their level of specialization. The four categories are:

- Service: Towns that provide a variety of services, such as education and healthcare.

- Trade: Towns that are home to retail businesses and wholesale markets.

- Manufacturing: Towns that are home to manufacturing industries.

- Diversified: Towns that have a mix of economic activities.

Functional Classification of Indian Cities

Functional classification of Indian cities is a method of categorizing urban centers in India based on their primary functions and specializations. Here are some of the most well-known functional classifications of Indian cities:

M.S. Mehta’s classification (1964)

Mehta classified Indian cities into five categories: administrative, industrial, commercial, educational, and cultural.

G.S. Aurora’s classification (1966)

Aurora classified Indian cities into six categories:

metropolitan cities, state capitals, district headquarters, industrial cities, commercial cities, and tourist cities. This classification is based on the size and functions of cities.

R.L. Singh’s classification (1971)

Singh classified Indian cities into four categories:

metropolises, large cities, medium-sized cities, and small cities. This classification is based on the population size of cities.

Here are some examples of Indian cities classified by their functions:

Functional Classification of Indian Cities | |

Function | Cities |

Administrative centers | New Delhi, Mumbai, Chennai, Kolkata, Bengaluru |

Industrial centers | Ahmedabad, Surat, Pune, Kanpur, Jamshedpur |

Commercial centers | Mumbai, Delhi, Bengaluru, Chennai, Kolkata |

Educational centers | Pune, Delhi, Bengaluru, Hyderabad, Kolkata |

Cultural centers | Jaipur, Udaipur, Varanasi, Amritsar, Madurai |

Transport hubs | Delhi, Mumbai, Chennai, Kolkata, Bengaluru |

Recreational centers | Goa, Manali, Shimla, Nainital, Udaipur |

Problems with Functional Classification of Cities

The following are some of the major issues with the functional classification of towns:

- Most settlements perform many functions and cannot be precisely slotted into one category.

- With development, lower-order towns take up higher-order functions. Hence, the classification becomes less relevant.

- The functional classification does not consider aspects like spatial expansion and infrastructure development of towns.

Slums are marked by substandard housing, overcrowding, and insecure tenure, where residents may not have legal ownership of the land or homes they occupy. These conditions lead to heightened vulnerability to environmental hazards such as floods, fires, and diseases. Slum dwellers often face social and economic marginalization, with limited access to education, healthcare, and employment opportunities.

The growth of slums is closely linked to rural-to-urban migration, where people move to cities seeking better livelihoods but are unable to afford proper housing. This creates informal settlements on the outskirts of cities or within neglected urban areas. Despite these challenges, slums are also hubs of informal economies, fostering entrepreneurship and community networks.

Addressing the issues of urban slums requires a multi-faceted approach. Governments and urban planners must focus on providing affordable housing, improving infrastructure, and enhancing access to basic services. Slum upgrading programs, which aim to improve living conditions without displacing residents, have proven successful in many cases. Additionally, policies promoting inclusive urban development and poverty alleviation are crucial for addressing the root causes of slum formation.

While urban slums present significant challenges, they also highlight the resilience and resourcefulness of their inhabitants. Proper interventions can transform these areas into vibrant, sustainable communities.

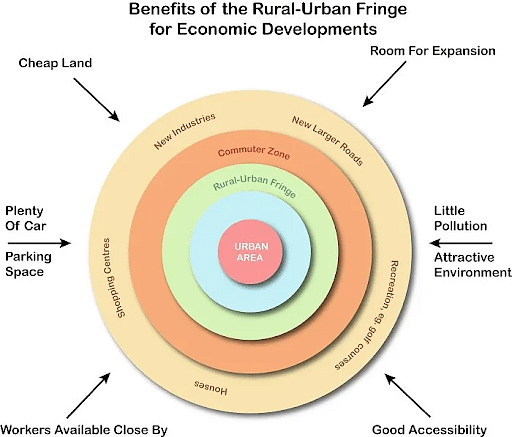

The rural urban fringe is a transition zone between city and country where rural and urban land use coexist. The fringe exists in the agricultural hinterland, where land use is changing, and is characterised in relation to the metropolis. The rural-urban fringe is a transitory zone that has lately been identified by the presence of rural and urban groups on sociological grounds. However, contemporary means of communication, as well as means of people and products mobility, have effectively disseminated the social views between the two groups of rural and urban dwellers.

Rural Urban Fringe

- The interface zone between the city’s entirely urban industrial, urban commercial physical expansion and the absolute rural agricultural landscape with village panchayat system, where new urban land use is replacing rural land use as well as occupational pattern, is referred to as the rural-urban fringe.

- It’s the point where the city and the countryside collide.

- It is a transitional zone between agricultural and other rural land uses and urban land uses.

- The fringe, which is well inside the urban sphere of influence, is defined by a diverse range of land use, including dormitory communities and houses for middle-income commuters who work in the centre metropolitan region.

- At the municipal border of the rural-urban fringe, suburbanization occurs.

- Many academics have attempted to draw attention to the differences in such comparable circumstances.

- Kurz and Fletcher attempted to define the distinction between fringe and urban regions in 1958. Wissink coined the terms fringe, suburb, and faux suburb in 1961.

- It is outside of the city’s formal boundaries, the rural-urban fringe is a neglected area. Many academics refer to the peripheral area by various names.

- Burgess refers to it as a “peripheral zone,” whereas the Census of India refers to it as an “Out Urban Area.” Some refer to it as the “Rural-Urban Continuum.”

Rural-Urban Fringe

Historical Development

- Following WWII, there was a flurry of inner-city buildings. However, this did not provide adequate homes for everyone who needed it.

- Others were constructed on the outskirts of towns and cities.

- The majority of residential development is occurring in the suburbs. The population density is lower than in the city centre, and the residences are often larger due to the reduced cost of land.

- As residential development extended to the suburbs, a transportation network grew, strengthening the suburbs’ access to the metropolis.

- Out-of-town retail areas have benefited from decreased land prices and additional space since the 1970s.

- Many cities have been losing population due to counter-urbanization since the late 1970s, with individuals departing for a variety of reasons.

- People seek a better quality of life in a rural setting that is calmer and cleaner.

- More individuals are willing and able to travel longer distances to work. Businesses are relocating to areas with better transportation links and lower construction costs.

- Part-time home working has risen as a result of flexible working and new technologies.

- People who have retired depart the city where they formerly worked.

- As a result, smaller towns and villages in locations with good communication links have expanded, resulting in a lot of ‘in-filling.’ Up-filling is the process of filling in gaps inside a village or town’s boundaries.

Characteristics

Land use Characteristics

- The pattern of land usage is always shifting.

- The residential sector is rapidly expanding.

- Small farms with extensive agricultural production are common.

- Service and other public services are insufficient.

- Development of science and business parks.

- Expansion of the airport

- Speculative construction is widespread.

Social Characteristics

- Rural urban periphery, also known as “Greenfield site” (undeveloped land outside of an existing built-up metropolitan region), is favoured by major corporations looking for new places for headquarters, offices, residences, and industrial estates.

- As a result, land usage is functionally and socially segregated.

- Selective Immigration: The rural urban edge draws residents from the middle class, who make up a tiny but strong and economically significant section of the city’s population.

- In the fringe region, service and other public amenities are insufficient, leading to immigration.

- Commuting: People who live on the outskirts of town have to commute to work every day.

- This leads to a twofold problem of traffic congestion in the city, with the local government being tasked with providing transportation services that can handle peak loads.

Types

- The rural-urban fringe is a vibrant area. With the expansion of urban facilities, it alters its shape and boundaries.

- The fringe area is divided into two categories.

- The primary urban fringe

- Secondary urban fringe

- The primary urban fringe is a strip that runs along the city’s administrative boundary.

- It sees quick expansion of urban infrastructure and diverse activities after development.

- It’s known as ‘True fringe’ by Myres and Beegle, ‘Inner fringe’ by Whiteland, and ‘Inner fringe or urban-suburban fringe’ by MMP Sinha.

- Secondary urban fringe – A secondary urban fringe is a region that is beyond the primary urban fringe.

- It has a lot of rustic traits that have taken a long time to establish. There are fewer functions in the city.

Structure

- Suburban expansion, the urban corridor, housing complexes, and village panchayats that have been converted into newly residential urban villages characterise the urban fringe.

- It includes urban land uses such as crematoriums, sewage treatment facilities, polluting industrial units, industrial slums, and the unplanned expansion of urban commercial marketplaces.

- Rural land use continues to dominate, and occupational shifts are more visible than landscape shifts. This is the city’s rubbish dump or dumping site.

- Urban shadow: This is the region where the fringe will spread in the future, and it is experiencing increased land pressure, urbanisation, and is mostly characterised by market gardening.

- The area is still rural, and land prices are skyrocketing.

- The daily urban system, also known as the commuter’s zone, is a zone where individuals commute to the rural urban edge to sell, buy, do business, and trade with city businesspeople.

- There are functionally connected villages that serve as daily city demand suppliers.

- The broadest possible area of urban impact is referred to as a city region.

Stages of Growth

- Rural stage: Agriculture land usage is mostly focused on intensive grain production at this stage.

- The village panchayat and local culture are dominant, with little urban impact.

- Changes in agricultural land use: The city’s influence has arrived, and agriculture has been modified to fulfil the city’s needs.

- Intensive grain cultivation has been replaced with market gardening items and dairy.

- Occupational transition: Agricultural labourers and cultivators are becoming city workers in the tertiary/service sector.

- Many farmers have become landless as a result of the high cost of land, which is necessary for municipal purposes.

- Over the course of the region, crematoriums, sewage treatment facilities, airports, bus stations, industrial units, Small Townships, and suburbs emerge.

- There are also slum and squatter colonies.

- Almost every area of the country’s environment has been converted to urban land use at this time.

- The development of colonies, hypermarkets, marketing centres, and wholesale markets.

- Unplanned and chaotic expansion characterises this era, resulting in urban misery.

- As a result, rapid urban strategy is essential for the region’s regeneration.

- Finally, as part of the reconstruction plan, the urban hamlet will be mixed in with the main city.

Reasons for Development

- The following are some of the main causes behind the growth of fringe areas.

- Population Growth

- Increased wealth and income

- Technologies of transportation and communication

- Increased capital expenditures on new infrastructure.

- External and internal forces are primarily responsible for the growth of the rural urban fringe.

- Internal forces: People are more likely to leave the city and dwell in the countryside as a result of these causes.

- Due to a lack of space in the city, the cost of land leasing is rising.

- Degradation of the environment

- There is a scarcity of housing.

- Land is in higher demand for tasks that can’t be performed in the city centre.

- External factors: These operate as an attracting element.

- commuting service (developed transport)

- Land is inexpensive.

- Municipal taxes are not applicable.

- Stability of the environment

Demarcation

- The delineation of the Fringe zones is a serious issue.

- Many academics have expressed various points of view. Cities have different qualities and purposes.

- In determining the boundaries of the region, the researchers took into account a number of elements.

- There are two strategies for separating the rural and urban areas.

- Empirical method

- Statistical method

Empirical method

- The empirical approach is a very old method that assumes a continuous built-up region as a demarcation foundation.

- For the delimitation of the fringe belt zone, the following indices might be used as a starting point.

- alterations in land usage

- In the built-up area, there have been several changes.

- House types Occupational structure of the population

- Industrial and non-agricultural activities are distributed.

- Essential services are limited.

- The distribution of educational institutions..

- Based on direct observation, the Rural Urban Fringe was studied at a distance of 10-20 kilometres from the city’s municipal limits.

- The following criteria were observed during the Indian census:

- The population density must be fewer than 400 people per square kilometre.

- The population growth rate over a decade should be at least 40%.

- There should be more than 800 girls for 1000 males in the sex ratio (due to outmigration for work)

- Bus or local train service should be available at the city’s outskirts.

- Male workers in non-agricultural occupations account for 50% or more of the workforce.

Statistical method

- In 1980, Dr. M.M.P. Sinha used statistical approaches to demarcate the urban outskirts.

- With the aid of Isochrone, he attempted to determine the influence area first. He calculated the word limit to be (T) 100.

- Outside, the region is regarded as 0. The urban index ranges from 0 to 100, with values assigned to the number of settlements.

- A link has been discovered between all of the village’s elements. Villages with values of less than +30 and -30 have been omitted. The scale of urbanity is determined by taking the mean value of all other parameters.

- The population density diminishes as we walk out from the city. Away from the metropolis, the sex ratio rises. This results in a positive correlation.

- It is now appropriate to classify it as

- Inner fringe zone or area of convenience

- Outer fringe zone or slowly progressive zone.

Issues

- Growth that is unplanned and chaotic.

- With land pollution and subsurface pollution, urban rubbish and the city’s dumping site are polluting the environment.

- sewage treatment plants, crematoriums

- Slums and their ramifications

- Property speculation, concentration of land ownership, and fast growing land values plague the periphery area.

- Polluting industries are being sent to the fringe.

- Because the urban temperament differs from the rural temperament, crime and vandalism result from the interplay of two interacting civilizations.

- Changes in social psychology and social alignments are taking place. Beliefs are shattered, and society and families are experiencing increasing disturbances.

- There is a lack of water sources, there is no public sewage disposal, and the streets are not well-planned.

- Small towns and revenue villages outside of municipalities lack administrative and financial infrastructure.

- The outskirts are served by inadequate public transportation.

Benefits

- Land is less expensive – since the Rural-Urban Fringe is less accessible than the inner city, and because most people must commute to the inner city for employment, fewer people are prepared to reside there.

- As a result, land prices are lower.

- There is less traffic congestion and pollution – because the neighbourhood is a new development on the periphery with a smaller population than the central city, there is less traffic congestion and pollution.

- It is a modern development with plenty of land, it has simpler access and improved road infrastructure.

- More open space creates a more pleasant atmosphere; yet, as development progresses, the quantity of open space reduces, as does the friendly environment.

- The rural-urban fringe is defined by a diverse range of land uses, the majority of which need enormous tracts of land.

- As urban sprawl continues, new housing projects are being built.

- Parks for science and business

- Supermarkets and hypermarkets

- Out-of-town shopping malls and retail parks

- Changes in the workplace

- Hotels and conference centres are available.

- Expansion of the airport

Benefits of Rural-urban Fringe

Conclusion

Rapid urbanisation has long been a prominent element of the global landscape. Today’s cities are undergoing fast transformation. They are expanding in size and number while also developing a distinct personality. The rural-urban fringe is the transition zone between the city’s totally urban industrial and commercial physical growth and the absolute rural agricultural landscape with village panchayat system, where new urban land use and occupational patterns are replacing rural land use and pattern.

Migration of population refers to the movement of people from one place to another, either within a country (internal migration) or across international borders (international migration). It is a significant demographic process influenced by various push and pull factors.

Push factors are conditions that drive people away from their place of origin, such as poverty, unemployment, political instability, natural disasters, or lack of access to education and healthcare. For example, conflicts or environmental degradation can force individuals to migrate in search of safety and better living conditions.

Pull factors, on the other hand, attract individuals to a new location. These include opportunities for employment, better living standards, access to quality education, and political stability. Developed countries or urban areas often attract migrants due to these advantages.

Migration can take various forms:

- Voluntary Migration: Where individuals move willingly, often for better opportunities.

- Forced Migration: Caused by circumstances such as war, persecution, or environmental crises.

- Seasonal Migration: Temporary movement for activities like agriculture or tourism.

- Rural-to-Urban Migration: Common in developing countries, driven by the search for jobs and better amenities in cities.

While migration can have positive effects like cultural exchange, economic growth, and remittances, it can also lead to challenges. These include overpopulation in urban areas, brain drain in the origin regions, and social integration issues in the destination areas.

Effective migration policies and support systems are essential to harness the benefits of migration while mitigating its challenges, ensuring a balanced and equitable approach to population movement.

The optimum population means the number of people an area can support sustainably. It balances the needs of society and the environment. The population is high enough to enable economic growth yet low enough to avoid overusing resources.

What is Optimum Population?

Every country has a limited amount of land, water, forests, minerals and other natural resources. There are also limits to the jobs, food and infrastructure that a country can provide. Given these limits, there is an optimum level of population that a country can support sustainably. This level of population is known as the optimum population.

Factors Leading to Optimum Population

Factors Leading to Optimum Population are:

- Available land: The amount of land that can grow crops and raw materials is the first important factor. A place can only make a fixed amount of crops based on its total land. When more people live there than the land can feed, a lack of food and other resources starts. So the ideal population depends on how many people the land can support.

- Jobs and work: Another big factor is the number of jobs and work opportunities in an area. A place can only provide limited work based on its industries, services and businesses. When more people live there than the jobs, a lot of unemployment happens. This affects living standards. So the ideal population matches the number of people available jobs can employ well.

- Resources and buildings: The fixed amount of resources, machines and buildings like roads, schools and hospitals in a place also affects its ideal population. When there are too many people, the existing buildings get too full and cannot meet needs well. So the ideal population matches the number of people existing resources and buildings can serve well.

- Environment: How much the environment of an area can hold is another factor. When more people live there than the environment can deal with well, problems like pollution, resource loss, and deforestation happen. So ideal population matches the number of people the environment can support well.

- Living standards: For a place to give the highest wealth and comfort to residents, the population must match the available resources and opportunities. When the population goes over ideal levels, lack of resources affects living standards through unemployment, high prices, and poor healthcare. So ideal population ensures the most wealth, happiness and income for citizens.

- Technology: Advances in farming techniques, making methods and resource use can increase a place’s ideal population size. New methods allow the same land, jobs and resources to serve more people well. But technology alone cannot support unlimited population growth. There are always real limits that set an ideal population.

- Lifestyle: The way of life and spending habits of a place’s citizens also affect its ideal population. Lifestyles that use resources less allow the same land and jobs to serve more people well. But only up to a point. There are basic human needs that set the minimum resources needed to support any number of people.

Theories of Optimum Population

The major theories of the optimum population are:

Thomas Malthus’ Theory of Optimum Population

Thomas Malthus was an English economist and scholar. In 1798, he wrote “An Essay on the Principle of Population”. In this essay, he discussed his theory on optimum population.

- Malthus observed that the human population has the ability to grow rapidly while the ability to produce food and resources grows slowly. According to him, food production can only increase arithmetically while population can increase geometrically.

- If left unchecked, human numbers will eventually outstrip food supply. This will cause a scarcity of food and resources. People will suffer hardships like poverty, starvation and disease.

- To keep the population in balance with resources, nature uses “preventive checks” and “positive checks”.

- Preventive checks include late marriages and moral restraint.

- Positive checks include war, disease and famine.

- For Malthus, the optimum population for a region was the number of people the resources could sustain indefinitely without people living in hardship.

- Once the population exceeds the optimum level, there will be pressures on food, housing, jobs and other necessities. This will lower living standards.

- To maintain an optimum population, Malthus suggested moral restraint, delayed marriages and reducing birth rates.

- Malthus opposed giving aid to the poor. He felt this would allow them to reproduce more, making the imbalance between population and resources worse.

- Population pressure poses a threat to food security. Many nations struggle to feed their growing populations.

- Rising populations cause constraints on resources like water, land, minerals and energy.

- Overpopulation leads to unemployment, poverty and suffering, especially in developing nations.

- However, technological progress has increased food production and resource efficiency. But rising populations consume these gains.

- In conclusion, though controversial, Malthus’ theory highlights the unsustainability of endless population growth. It forces us to think of ways to manage population size to optimize resource use and improve living standards.

Dalton’s theory of Optimum Population

Dalton thought that there was the best size for the human population. This size brings maximum happiness and richness to people. He said for a country or place to have the most wealth and growth, its population should be a certain size. The size should not be too big and not too small.

- Based on what he saw, Dalton decided that the best population size is reached when land, food and jobs fully give for the needs of the people living there. When the population goes over that best level, poverty and unemployment start due to fewer resources.

- Dalton came to this result by studying the towns and villages in England in the 1700s and 1800s. He saw that small villages with very few people often lacked enough things and services. But places with too many people started having unemployment, high prices and bad living conditions.

- As per Dalton’s theory, small populations lack things needed for good growth, like specialized workers, capital and a big market for products. But when the population grows over the best level, the resources required, like land, jobs and food, become less.

- When a population fully uses these 3 factors – land, labour and capital – without overusing any of them, then that population has reached the best size, ensuring maximum wealth and prosperity. But if the population grows further and starts overusing even one of these factors, then poverty starts coming up.

- Dalton applied this theory to calculate the best population for Britain at that time. He thought that available cultivable land in Britain could best support 22 million people. Also, at that time, Britain had 7 million labourers that could work the available land. So he estimated that Britain’s best population would be around 20-22 million.

- Really, Britain’s population at the time was around 16 million. So Dalton predicted that Britain could absorb around 5-6 million more people while still providing prosperity and growth for all. However, he warned that excessive population growth of over 22 million would lead to overcrowding, poverty and hardship.

- Dalton’s theory of best population highlights the important connection between population size, available resources and living standards. It shows that for a place to grow rich, its population needs to be in balance with the land, capital and jobs available there. Extra population leads to unemployment, while too small a population lacks growth.

- The theory is important even today for balancing population growth with socioeconomic progress. Most economists accept that the best population level exists for places beyond which population pressure starts degrading living standards. However, deciding the best size dynamically remains difficult due to complexities in economies.

Carrying capacity of the Earth

The carrying capacity is the maximum population size that the Earth’s resources can sustain indefinitely. If human numbers exceed the carrying capacity, it will lead to environmental degradation and hardship. The optimum population size is less than or equal to the carrying capacity of the Earth. Scientists believe that we are already exceeding the planet’s sustainable limit.

Demographic transition refers to the shift in population dynamics as a society progresses from high birth and death rates to low birth and death rates. This process occurs in distinct stages, closely linked to economic development, industrialization, and social changes. It is a key concept in population studies, explaining changes in population growth over time.

Stage 1: High Stationary Stage

In this stage, both birth rates and death rates are high, leading to a relatively stable population with slow growth. Societies in this stage are typically pre-industrial, relying on subsistence agriculture with limited healthcare and sanitation.Stage 2: Early Expanding Stage

Advancements in medicine, sanitation, and nutrition lead to a significant decline in death rates, while birth rates remain high. This results in rapid population growth, often seen during early industrialization.Stage 3: Late Expanding Stage

Birth rates begin to decline due to urbanization, improved education, especially for women, and access to family planning. Population growth slows as the gap between birth and death rates narrows.Stage 4: Low Stationary Stage

Both birth and death rates are low, stabilizing the population. This stage is characteristic of developed societies with advanced economies and high standards of living.Stage 5: Declining Stage (optional)

Some societies experience a decline in population as birth rates fall below replacement levels, leading to concerns about aging populations and workforce shortages.

The demographic transition model highlights the link between population trends and socio-economic development. It provides valuable insights for policy planning, particularly in areas like healthcare, education, and resource management, ensuring sustainable growth and well-being.

Family planning is the consideration of the number of children a person wishes to have, including the choice to have no children, and the age at which they wish to have them. Things that may play a role on family planning decisions include marital situation, career or work considerations, financial situations. If sexually active, family planning may involve the use of contraception (birth control) and other techniques to control the timing of reproduction.

Other aspects of family planning aside from contraception include sex education, prevention and management of sexually transmitted infections, pre-conception counseling and management, and infertility management. Family planning, as defined by the United Nations and the World Health Organization, encompasses services leading up to conception. Abortion is not typically recommended as a primary method of family planning.

Family planning is sometimes used as a synonym or euphemism for access to and the use of contraception. However, it often involves methods and practices in addition to contraception. Additionally, many might wish to use contraception but are not necessarily planning a family (e.g., unmarried adolescents, young married couples delaying childbearing while building a career). Family planning has become a catch-all phrase for much of the work undertaken in this realm. However, contemporary notions of family planning tend to place a woman and her childbearing decisions at the center of the discussion, as notions of women’s empowerment and reproductive autonomy have gained traction in many parts of the world. It is usually applied to a female-male couple who wish to limit the number of children they have or control pregnancy timing (also known as spacing children).

Family planning has been shown to reduce teenage birth rates and birth rates for unmarried women.

Urban and rural settlements differ significantly in terms of population size, infrastructure, economic activities, and lifestyle. These distinctions reflect the diverse ways people organize themselves and interact with their environments.

Urban settlements are characterized by high population density, advanced infrastructure, and a concentration of economic activities. They serve as centers of commerce, industry, and services, with a focus on secondary and tertiary sectors. Urban areas are marked by well-developed transportation networks, healthcare facilities, educational institutions, and modern amenities. The lifestyle in urban settlements tends to be fast-paced, with greater opportunities for employment and cultural activities. Examples include cities, towns, and metropolises.